Cozumel

Cozumel (Spanish pronunciation: [kosuˈmel], Yucatec Maya: Kùutsmil) is an island and municipality in the Caribbean Sea off the eastern coast of Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula, opposite Playa del Carmen. It is separated from the mainland by Cozumel Channel and is close to the Yucatán Channel. The municipality is part of the state of Quintana Roo, Mexico.

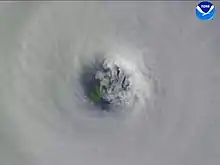

Satellite image of Cozumel Island in 2001 | |

Location of Cozumel in Quintana Roo State | |

Cozumel | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Caribbean Sea |

| Coordinates | 20°25′N 86°55′W |

| Total islands | 2 |

| Area | 647.33 km2 (249.94 sq mi) |

| Highest point | 14m |

| Administration | |

| State | Quintana Roo |

| Municipality | Cozumel |

| Largest settlement | San Miguel de Cozumel (pop. 77,236) |

| Presidente municipal (Municipal president) | Pedro Joaquín Delbouis (PRI) |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 100,000 (2011) |

| Pop. density | 154.5/km2 (400.2/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Maya |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

| Official website | Government website |

| Official name | Parque Nacional Arrecifes de Cozumel |

| Designated | 2 February 2005 |

| Reference no. | 1449[1] |

| Official name | Manglares y Humedales del Norte de Isla Cozumel |

| Designated | 2 February 2009 |

| Reference no. | 1921[2] |

The economy of Cozumel is based on tourism, with visitors able to benefit from the island's balnearios, scuba diving, and snorkeling. The main town on the island is San Miguel de Cozumel.

Etymology

The name Cozumel was derived from the Mayan "Cuzamil" or "Ah Cuzamil Peten" in full, which means "the island of swallows" (Spanish: Isla de las Golondrinas).[3][4]

Geography

The island is located in the Caribbean Sea along the eastern side of the Yucatan Peninsula about 82 km (51 mi) south of Cancún and 19 km (12 mi) from the mainland. The island is about 48 km (30 mi) long and 16 km (9.9 mi) wide. With a total area of 477.961 km2 (184.542 sq mi), it is Mexico's largest Caribbean island, largest permanently inhabited island, and Mexico's third-largest island, following Tiburón Island and Isla Ángel de la Guarda.

The majority of the island's population lives in the town of San Miguel (pop. 77,236 in 2010),[5] which is on the island's western shore. The municipality, which includes two small areas on the mainland enclaved within the Municipality of Solidaridad with a land area of 10.423 km2 (4.024 sq mi), has a total land area of 647.33 km2 (249.94 sq mi).[6]

Large parts of the island are covered with mangrove forest which has many endemic animal species. Cozumel is a flat island based on limestone, resulting in a karst topography. The highest natural point on the island is less than 15 m (49 ft) above sea level. The cenotes are deep water-filled sinkholes formed by water percolating through the soft limestone soil for thousands of years. Cozumel's cenotes are restricted to qualified cave divers with appropriate credentials.

Fauna

Endemic species and subspecies of bird include:

- the Cozumel emerald

- the Cozumel great curassow, which is vulnerable

- the Cozumel thrasher, which is nearly, if not already, extinct

- the Cozumel vireo

- the Cozumel wren

Endemic dwarf mammals are found on the island:

- the Cozumel fox, which is nearly, if not already, extinct[7]

- the Cozumel Island coati, which is endangered.[8]

- the Cozumel Island raccoon, which is critically endangered[9][10]

There are three rodents that are larger than their mainland counterparts: Oryzomys couesi, Peromyscus leucopus, and critically endangered Reithrodontomys spectabilis, the latter of which is also endemic to the island.

Endemic marine life:

Other native wildlife includes:

- the American crocodile

- the black spiny-tailed iguana

- the blue land crab (Cardisoma guanhumi)

Invasive species include:

Coral reefs

Cozumel is surrounded by a diverse ecosystem of coral reefs that is home to more than 1,000 marine species.[12] The reefs are primarily found on underwater cliffs, there are also some in coastal lagoons and on sand bars at the north tip of the island.[13] They are part of the much larger Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System which is the second largest reef in the world, stretching over 1,000 kilometers (620 mi).[14] Cozumel's deeper coral reefs were historically famed for their black corals,[15] yet black coral populations declined from the 1960s to the mid-1990s because of overharvesting[15] and by 2016 had not recovered.[16] A huge portion of the reef on the south side of island is sectioned off into the Arrecifes de Cozumel National Park. This park is protected under the Ramsar Convention along with Manglares y Humedales del Norte de Isla Cozumel, they both are included in the UNESCO protected area called Isla Cozumel Biosphere Reserve, Mexico.[17] The site includes the coral reefs on the southern coast of Cozumel. The reefs in Cozumel are made up of hard coral and soft coral. The marine life that inhibit the reefs include zoanthids, polychaets, actinarians, hydroids, sponges, crustaceans, mollusks, echinoderms and many varieties of Caribbean fish. The park is also a habitat to several endangered marine species such as the loggerhead sea turtle, hawksbill sea turtle, queen triggerfish, and the endemic splendid toadfish.[18] Due to the abundant marine life and coral reefs the clear and warm Caribbean water, Cozumel is considered one of the best scuba-diving destinations in the world.[19]

Climate

Cozumel has tropical savanna climate under the Köppen climate classification that closely borders on a tropical monsoon climate.[20] The dry season is short, from February to April, but even in these months precipitation is observed, averaging about 45 millimetres (1.8 in) of rain per month. The wet season is lengthy, covering most of the months, with September and October being the wettest months, when precipitation averages over 240 millimetres (9.4 in). Thunderstorms can occasionally occur during the wet season.[21] Temperatures tend to remain stable with little variation from month to month though the temperatures are cooler from December to February with the coolest month averaging 22.9 °C (73.2 °F). Owing to its proximity to the sea, the island is fairly humid, with an average humidity of 83%.[21] The wettest recorded month was October 1980 with 792 millimetres (31.2 in) of precipitation and the wettest recorded day was June 19, 1975, with 281 millimetres (11.1 in).[21] Extremes range from 9.2 °C (48.6 °F) on January 18, 1977 to 39.2 °C (102.6 °F).[21]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 36.4 (97.5) |

36.0 (96.8) |

34.7 (94.5) |

39.0 (102.2) |

36.6 (97.9) |

36.4 (97.5) |

39.2 (102.6) |

36.8 (98.2) |

36.6 (97.9) |

36.1 (97.0) |

35.2 (95.4) |

32.6 (90.7) |

39.2 (102.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 28.6 (83.5) |

29.1 (84.4) |

30.9 (87.6) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.7 (90.9) |

32.4 (90.3) |

32.6 (90.7) |

33.0 (91.4) |

31.9 (89.4) |

30.7 (87.3) |

29.7 (85.5) |

28.6 (83.5) |

31.0 (87.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 22.9 (73.2) |

23.2 (73.8) |

24.7 (76.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.7 (80.1) |

25.9 (78.6) |

24.8 (76.6) |

23.4 (74.1) |

25.5 (77.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 19.4 (66.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

20.7 (69.3) |

21.8 (71.2) |

22.9 (73.2) |

23.8 (74.8) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.6 (74.5) |

23.1 (73.6) |

21.7 (71.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

22.0 (71.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 9.2 (48.6) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.4 (52.5) |

14.6 (58.3) |

15.2 (59.4) |

18.8 (65.8) |

17.0 (62.6) |

20.8 (69.4) |

20.8 (69.4) |

17.0 (62.6) |

11.2 (52.2) |

12.7 (54.9) |

9.2 (48.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 81.4 (3.20) |

60.0 (2.36) |

32.2 (1.27) |

44.8 (1.76) |

110.6 (4.35) |

191.7 (7.55) |

115.5 (4.55) |

141.7 (5.58) |

240.2 (9.46) |

242.5 (9.55) |

122.5 (4.82) |

106.8 (4.20) |

1,489.9 (58.66) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 8.66 | 6.46 | 4.03 | 3.73 | 7.20 | 12.63 | 11.83 | 13.37 | 15.43 | 15.70 | 11.06 | 9.76 | 119.86 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82 | 81 | 79 | 79 | 80 | 84 | 84 | 84 | 87 | 85 | 83 | 83 | 83 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 198.0 | 192.3 | 232.0 | 257.0 | 231.9 | 206.5 | 220.1 | 221.7 | 181.5 | 193.7 | 183.9 | 192.2 | 2,510.8 |

| Source: Colegio de Postgraduados[21] | |||||||||||||

History

The Maya are believed to have first settled Cozumel by the early part of the 1st millennium AD, and older Preclassic Olmec artifacts have been found on the island as well. The island was sacred to Ix Chel, the Maya Moon Goddess, and the temples here were a place of pilgrimage, especially by women desiring fertility.[22] There are a number of ruins on the island, most from the Post-Classic period. The largest Maya ruins on the island were near the downtown area and have now been destroyed.[23] Today, the largest remaining ruins are at San Gervasio, located approximately at the center of the island.

The first Spanish expedition to visit Cozumel was led by Juan de Grijalva in 1518.[24]:28 In the following year Hernán Cortés stopped by the island on his way to Veracruz.[24]:57 The Grijalva and Cortés expeditions were both received peacefully by the Maya of Cozumel, unlike the expeditions' experiences on other parts of the mainland. Even after Cortés destroyed some of the Maya idols on Cozumel and replaced them with an image of the Virgin Mary, the native inhabitants of the island continued to help the Spanish re-supply their ships with food and water so they could continue their voyages. Gerónimo de Aguilar was rescued at this time.[24]:60–64

As many as 10,000 Maya lived on the island then, but in 1520, infected crew members of the Pánfilo Narváez expedition brought the smallpox contagion to the island and by 1570 only 186 men and 172 women were left alive on Cozumel. In the ensuing years Cozumel was often the target of attacks by pirates, and in 1650 many of the islanders were forcibly relocated to the mainland town of Xcan Boloná to avoid the Buccaneers’ predation. Later, in 1688, most of the rest of the island's population, as well as many of the settlements along the Quintana Roo coast, were evacuated inland to towns such as Chemax.

In 1848, refugees escaping the tumult of the Caste War of Yucatán settled on the island and in 1849 the town of San Miguel de Cozumel was officially recognized by the Mexican government.[25]

In 1861, American President Abraham Lincoln ordered his Secretary of State, William Henry Seward, to meet with the Mexican chargé d'affaires Matias Romero to explore the possibility of purchasing the island of Cozumel for the purpose of relocating freed American slaves offshore. The idea was summarily dismissed by Mexican President Benito Juarez, but in 1862 Lincoln did manage to establish a short-lived colony of ex-slaves on Île à Vache off the coast of Haiti.[26]

Although the original airport was a World War II relic and was able to handle jet aircraft and international flights, a much larger airport was built in the late 1970s.

Scuba diving is still one of Cozumel's primary attractions, mainly due to the coral reef on the western shore of Cozumel. These coral reefs are protected from the open ocean by the island's natural geography. In 1996, the government of Mexico also established the Cozumel Reefs National Marine Park, forbidding anyone from touching or removing any marine life within the park boundaries.[27] Despite the importance of healthy reefs to Cozumel's tourist trade, a deepwater pier was built in the 1990s for cruise ships to dock, causing damage to the reefs, and it is now a regular stop on cruises in the Caribbean. Over the past few decades, coral reef health has significantly declined in Cozumel, with much lower coral cover now present than was historically recorded.[28][29]

The island was struck directly by two Category 4 hurricanes during the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season. In July, Hurricane Emily passed just south of Cozumel, exposing the island to the storm's intense inner core. Despite Emily being a powerful storm, it was the larger, stronger, slower-moving Hurricane Wilma that caused the most destruction when it hit the island in October.[30] Wilma's eye passed directly over Cozumel.

There was some damage to the underwater marine habitat. This included the coral reefs, which suffered particularly at the shallower dive sites, and the fish that inhabit the reefs.[31][32]

Economy

.jpg.webp)

Tourism, diving and charter fishing comprise the majority of the island's economy. There are more than 300 restaurants on the island and many hotels, some of which run dive operations, have swimming pools, private docks, and multiple dining facilities.

Other water activities include para-sailing, kitesurfing, and a tourist submarine. There are also two dolphinariums. At the cruise ship docks, there are several square blocks of stores selling Cuban cigars, jewellery, T-shirts, tequila, and a large variety of inexpensive souvenirs. Also, the only working pearl farm in the Caribbean[33] is located on the North edge of the island.

San Miguel is home to many restaurants with a huge variety of different cuisines, along with several discothèques, bars, cinemas, and outdoor stages. The main plaza is surrounded by shops; in the middle of the plaza is a fixed stage where Cozumeleños and tourists celebrate every Sunday evening with music and dancing.

All food and manufactured supplies are shipped to the island. Water is provided by three different desalination facilities located on the island.

Education

There are three universities on the island: the State Public University of Quintana Roo (UQROO)[34] and two private universities, the Partenon Institute[35] and the Interamerican University for Development (UNID).[36] In addition to teaching English as a degree program, they offer other career options including natural resources research, tourism and commercial systems.

Culture

Santa Cruz Festival and El Cedral Fair

The Festival of Santa Cruz and El Cedral Fair is a historical tradition held in the town of El Cedral, in the south of Cozumel Island at the end of April. This annual event is said to have been started over 150 years ago by Casimiro Cárdenas. Cárdenas was one of a group that fled to the island from the village of Saban, on the mainland, after an attack during the Caste War of Yucatánin 1848. The attackers killed other villagers, but Cárdenas survived whilst clutching a small wooden cross.

Legend has it that Cárdenas vowed to start an annual festival wherever he settled, to honor the religious power of this crucifix. Today, the original Holy Cross (Santa Cruz) Festival forms part of the wider Festival of El Cedral, which includes fairs, traditional feasts, rodeos, bullfights, music and competitions. The celebrations last about five days in all and are held every year at the end of April or beginning of May.[37]

Cozumel Carnival

The Cozumel Carnival or Carnaval de Cozumel is one of the most important carnival festivities in México. It has been celebrated as a tradition beginning from the late nineteenth century and fills Cozumel's streets with parades. It begins the week before Mardi-Gras in February. Cozumel's Carnaval is a tradition which has been passed down through many generations that celebrates a mixture of cultures that escaped to the warm embrace of Cozumel. Dating back to the mid-1800s, Cozumel Carnaval was started by young people dressed in vibrantly colorful costumes known as "Estudiantinas" or "Comparsas", who expressed themselves in the streets of Cozumel through the artforms of dance, song, and fantasy.[38]

Government

Cozumel Municipality is one of eleven municipalities of Quintana Roo. The municipal seat is located in San Miguel de Cozumel, the largest city in the municipality.

In popular culture

- Cozumel and its Mayan ruins are featured in the program I Shouldn't Be Alive Season 6, Episode 5: "Lost In The Jungle".

References

- "Parque Nacional Arrecifes de Cozumel". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- "Manglares y Humedales del Norte de Isla Cozumel". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Archived from the original on July 18, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- "Cozumel". Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México (in Spanish). Secretaría de Gobernación. Archived from the original on June 12, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- Holt, Patricia A. (2005). Cozumel: the complete guide. New York: iUniverse. p. ix. ISBN 978-0-595-36995-9.

- "2010 census tables: INEGI". Mapserver.inegi.org.mx. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- "Land area of islands in Mexico: INEGI". Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- "Cozumel Fox" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 13, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- "Coatis, Pisotes, or Coatimundis" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 12, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- K. McFadden, D. Vasco, A. Cuaron, D. Valenzuela and M. Gompper. 2009. Conservation and population assessment of the endangered dwarf carnivores from Cozumel Island. Biodiversity and Conservation 13:317–331

- "Cozumel Pygmy Raccoon" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 13, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2013.

- https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/A:1008815004072

- "Isla Cozumel Biosphere Reserve, Mexico". UNESCO. UNESCO. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- "Parque Nacional Arrecifes de Cozumel" [Reefs Cozumel National Park]. The Ramsar Convention Secretariat. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Gress, Erika; Voss, Joshua D.; Eckert, Ryan J.; Rowlands, Gwilym; Andradi-Brown, Dominic A. (2019), Loya, Yossi; Puglise, Kimberly A.; Bridge, Tom C.L. (eds.), "The Mesoamerican reef", Mesophotic coral Ecosystems, Springer International Publishing, 12, pp. 71–84, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-92735-0_5, ISBN 9783319927343

- Padilla, Claudia; Lara, Mario (2003). "Banco Chinchorro: The Last Shelter for Black Coral in the Mexican Caribbean". Bulletin of Marine Science. 73 (1): 197–202. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- Andradi-Brown, Dominic A.; Gress, Erika (July 4, 2018). "Assessing population changes of historically overexploited black corals (Order: Antipatharia) in Cozumel, Mexico". PeerJ. 6: e5129. doi:10.7717/peerj.5129. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 6035717. PMID 30013832.

- "Isla Cozumel Biosphere Reserve, Mexico". UNESCO. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- "Parque Nacional Arrecifes de Cozumel". The Ramsar Convention Secretariat. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- "Cozumel Island, Mexico". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J. R.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. (2006). "World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated" (PDF). Meteorol. Z. 15 (3): 259–263. Bibcode:2006MetZe..15..259K. doi:10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

- "Normales climatológicas para Cozumel, Q. ROO" (in Spanish). Colegio de Postgraduados. Archived from the original on February 21, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- Paxton, Merideth (2001). The Cosmos of the Yucatec Maya: Cycles and Steps from the Madrid Codex. University of New Mexico Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-0826322920.

- Hajovsky, Ric, 2011, Bases, Bulldozers and Bullshit, Archived September 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Diaz, B., 1963, The Conquest of New Spain, London: Penguin Books, ISBN 0140441239

- Hajovsky, Ric The Yellow Guide to the Mayan Ruins of San Gervasio, Cozumel, Amazon Books, 2012, pp. 8–10

- Hajovsky, Ric (2015). The True History of Cozumel. Dallas: Pan American Publishing. pp. 147–165. ISBN 9780982861080.

- Laskowski, Gloriana (July 1, 1999). "Cozumel An Island Paradise - 'Vistas De Cozumel'". Mexconnect. Mexconnect.com. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- Reyes-Bonilla, Héctor; Millet-Encalada, Marinés; Álvarez-Filip, Lorenzo (2014). "Community Structure of Scleractinian Corals outside Protected Areas in Cozumel Island, Mexico". Atoll Research Bulletin. 601: 1–13. doi:10.5479/si.00775630.601.

- Gress, Erika; Andradi-Brown, Dominic A. (July 4, 2018). "Assessing population changes of historically overexploited black corals (Order: Antipatharia) in Cozumel, Mexico". PeerJ. 6: e5129. doi:10.7717/peerj.5129. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 6035717. PMID 30013832.

- "Hurricane Wilma: The areas affected". BBC News. October 25, 2005. Retrieved July 24, 2005.

- "Species Richness and Community Structure of the Yucatan Marine Reserve Before and After 2005 Hurricane Season". Cmbc.ucsd.edu. Archived from the original on October 30, 2012. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- Calvin (March 6, 2007). "Cozumel Reef Conditions Update – 2007". Calvintang.com. Archived from the original on May 28, 2013. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- https://www.maineterrain.com/tour-pearl-farm/

- webmaster. "Unidad Académica Cozumel Universidad de Quintana Roo – Universidad de Quintana Roo" [Cozumel Academic Unit University of Quintana Roo - University of Quintana Roo]. www.uqroo.mx. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- "Inicio" [Start]. Instituto Partenón de Cozumel (in Spanish). Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- "Cozumel". www.unid.edu.mx. Archived from the original on March 18, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- "Cozumel Próximos Eventos – Fiestas de la Santa Cruz" [Cozumel Upcoming Events - Parties of the Santa Cruz]. cozumel.travel. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- "Carnival Cozumel 2016". www.carnavalcozumel.com.mx. Archived from the original on May 3, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Cozumel. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Cozumel at Curlie

- Cozumel Parks and Museums official site for the Quintana Roo State Foundation that manages Chankanaab Park, Punta Sur, San Gervasio and the Island Museum