Cyanography

Cyanography is an artistic practice that utilises a particular type of photographic reproduction – the cyanotype. Invented in 1842 by Sir John Herschel,[1] this process requires a material, commonly fabric or paper, to be coated in photosensitive solution – usually a combination of ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide.[2] This results in blue mono-tonal reproductions of the photographic negative, commonly called a blueprint.[1]

The cyanotype originated as a popular form of photographic reproduction due to its inexpensiveness and accuracy, making it useful for architectural and scientific purposes.[3] However, a significant part of cyanography's nature as a form of artistic expression emerges from the ways in which its reproduction of images can be manipulated or distorted.[4] Cyanography produces unique artistic effects as it involves the reversal of negative space, so spaces of light in the original photograph will be dark in the final print. Additionally, a cyanographic print can be created from actual objects to create a photogram, rather than only reproducing photographic negatives.[2] Equally important is the expressive results produced by the application of emulsion. As the image will only be printed on the photosensitive areas, artists are able to use painting techniques such as calligraphy, brushwork and using other application tools such as a cloth or reed to apply the solution to a material, producing a variety of effects.[2]

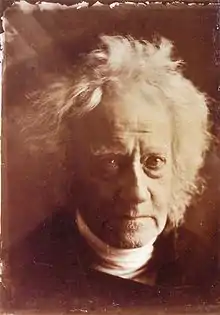

Origins

The cyanotype was invented by Sir John Herschel in 1842. Herschel's primary intention was not to create a method of photography, but rather to experiment with the general effect of light on iron compounds. He discovered that exposure to light turned a combination of ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide blue.[1] This methodology was then utilised for printing copies of photographic negatives.

The technique was then taken up and perfected by a few notable photographic practitioners of the time, including William Henry Fox Talbot, Anna Atkins and Henry Bosse.[5] These photographs often had a scientific aim, with botanical samples being a key subject of photographs at the time. The cyanotype also rose to be commonly used as a cost-effective method for reproducing architectural plans, scientific diagrams and notes or writing that required reproducing – in effect, an early version of a photocopier.[1]

While extremely popular with amateur photographers around this time, due to its ease and affordability,[3] cyanotypes were not considered to be properly photography. However, in 1903, when Kodak came out with a “Folding Pocket Camera” which used gelatin silver printing paper, most commercial printing paper also switched over to utilising the gelatin silver developing solution. This resulted in cyanotypes as a photographic printing process mostly disappearing in artistic spheres, with their use being relegated to architectural and engineering blueprints; as well as amateur photography.[6]

Techniques

The cyanotype process requires a material to be coated in a photosensitive solution – classically, a combination of ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide. There are two main options for exposing the solution to light. First, a photographic negative may be placed over the photosensitive material to produce a print. The second option is to place an actual object over the photosensitive material to produce a photogram – producing an outline of the object on the material.[6] When exposed to light, whatever is in shadow on the material will remain white, while whatever element of the material that is exposed to light will become a deep Prussian blue, creating a blue monotonal copy on the material underneath. Once exposed, the printed material is then dipped in a fixative solution so no further print will be made.[2] The material, after exposure, must be rinsed in water to remove the photosensitive chemicals and complete the cyanotype print. Cyanotype techniques can be applied to a wide variety of surfaces,[1] including paper, fabric, glass, Perspex and ceramics.[2]

The technique of creating a cyanotype has remained mostly unchanged since its inception over 170 years ago.[7] In 1994, Mike Ware (MA DPHIL CCHEM FRSC), invented a new cyanotype mixture which replaced the ferric ammonium citrate with ferric ammonium oxalate.[1] This has been the main change in cyanotype process since its inception. This solution resulted in a faster exposure time for cyanotypes, to prevent the prevalent problem of underexposure with the classical mixture. The cyanotype solution, even once its excess is washed off with water, remains photo-sensitive to some degree. A print that has been stored or displayed in bright light will eventually fade, the light causing a chemical reaction that changes the Prussian blue of the cyanotype to white. However, this process can be reversed by storing the cyanotypes in darkness. This will return them to their original vibrancy.[6]

Different composition levels of ferric ammonium citrate (or oxalate) and potassium ferricyanide will result in a variety of effects in the final cyanotypes. Mixtures of half ferric ammonium citrate and half potassium ferricyanide will produce a medium, even shade of blue that is most commonly seen in a cyanotype. A mix of one third ferric ammonium citrate and two thirds potassium ferricyanide will produce a darker blue, and a more high-contrast final print.[2]

Emergence of cyanography as an artistic practice

Initially after the cyanotype's invention, the medium was widely dismissed by practitioners of the time as a form of photographic reproduction without artistic merit. Considered to be outside the definition of actual photography, it was understood to be useful only for creating blueprints of architectural or scientific diagrams.[1] Amateurs were encouraged to experiment with cyanotype to develop their photographic development skills, but the value of the practice was considered to end there.

John Herschel, the inventor of the cyanotype, mostly used the method to reproduce pictures engraved on steel plates. As steel is very hardy, multiple prints could be made from the one original – with editions of around 10,000 being able to be reproduced before the plate became too worn.[1] The prints produced were stark contrasts of only blue or white, with no tonal variation in between as would later be achieved with making cyanotypes of photographic negatives.

Anna Atkins, an English photographer and botany specialist, was one of the first to publish a series of cyanotypes as an artist.[8] Her first book, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions (1842),[9] is generally considered to be the first published book illustrated with photographs.[10] While it is difficult to source an intact copy, the original contains over 411 cyanotype plates of various botanical specimens. While part of the purpose of these cyanotypes was scientific in nature, the prints are artistic in their aesthetic – and have served as inspiration for artists utilising cyanotypes ever since.[11]

While the use of cyanotypes mostly disappeared amongst the artistic community during World War I and II, as well as the post-war period, the 1950s and 1960s saw a resurgence of amateur photography methods in fine art.[2] The rediscovery of these techniques resulted in their repurposing from scientific copies to more experimental results. A key example is Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil’s collaborative cyanotypes, including Untitled (Double Rauschenberg), c.1950.[12] These prints were made by both artists lying down, hands held, on a large piece of photosensitive paper (treated with cyanotype chemicals). The resulting prints of their bodies in various poses are currently part of the Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection.[4]

Cyanography continued to grow slowly in popularity amongst contemporary artists from this time until the present. Notably, in 1995, Mike Ware developed a new way of developing cyanotypes by substituting ferric ammonium citrate with ferric ammonium oxalate – creating a fast-developing mixture that made the process more efficient, although some artists preferred the traditional method.[1] Cyanography remains a fairly unknown technique outside of photography specialists, although there are several contemporary artists dedicated to the medium such as Kate Corsden, Christian Marclay and Azul Loeve.[13]

The first museum exhibition dedicated entirely to the art of cyanography was in 2016, with the Worcester Art Museum’s Cyanotypes: Photography’s Blue Period.[6] The exhibition contained artistic cyanotypes from the early 1800s up to contemporary times, with an accompanying catalogue that also included a set of essays on the topic.[2]

Two years later, in 2018, the New York Public Library exhibited the work of nineteen contemporary cyanographic artists. Mounted 175 years after Anna Atkin’s first book of cyanotypes, British Algae, the exhibition was titled Anna Atkins Refracted: Contemporary Works.[14]

Cyanography as an artistic practice

Genre

Cyanography is considered to be a type of photography. However, it can also be categorised as a form of painting, particularly due to the variety of application possibilities for the photosensitive solution it relies upon.[1]

Artistic qualities

The success of a cyanotype as it was originally intended, as a blueprint or copy, is dependent on its closeness to the original.[2] There is a very different metric for success in cyanography, as the cyanotype’s success as a form of artistic expression is often due to the ways in which its reproduction of images can be manipulated or distorted.[4] This potentiality occurs in three key aspects.

The first is the way in which a cyanotype, like many other types of photography, produces a print that reverses the negative space of the original.[2] Spaces where light can pass through in the original photographic negative, or around an object placed over the photosensitive material, will be blue in the cyanotype. Space where light is blocked from light will be white in the final print. This produces a unique effect, as while white is often used to frame or highlight a central subject in many artistic mediums, the opposite is true in cyanography. Often, the artist has to think, in a manner of speaking, in reverse of the final effect they wish to produce, or give over to the medium and let their work be guided by whatever result is produced.[6]

Secondly, cyanography is not restricted to the reproduction of existing photographic negatives. Prints can be made of three-dimensional objects, utilising the ability of the objects to be placed on top of the photosensitive material. Once exposed to light, the final print is of an outline of an item.[2] Certain items are particularly effective in this, because fine details of can be filled in where light can filter through. For example, Anna Atkin’s botanical cyanotypes highlight the more transparent segments of a petal or leaf,[11] while Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil’s cyanotypes of their own bodies highlight the outlines and transparencies of the human form.[12]

Thirdly, the expressive results produced by the application of emulsion are extremely important to cyanography. As the image will only be printed on the photosensitive areas, artists are able to use painting techniques such as calligraphy, brushwork and using a cloth or reed (or any other implement) to apply the solution to a material in order to produce a variety of desired effects.[1] A photographic negative, or object placed over the work, will then only print on the places where the photosensitive solution has been applied.

The high potentiality for mistakes in the process and the lack of total control over a cyanotype’s outcome mean that accidental results are sometimes the most successful examples of cyanography.[2] In an essay written as part of the MoMA Heilbrunn Timeline of Art, Mia Fineman describes cyanographic prints as “…photographs that, through some technical error – a tilted horizon, an amputated head, a looming shadow, or inadvertent double-exposure – achieved a strange and unexpected visual charm.”[4]

Notable artists

Early Artists (1800-1900s)

Mid-Century Resurgence Artists (1950s-1980s)

- Robert Rauschenberg and Susan Weil

- Susan Derges

- Florian Neusüss

Contemporary Artists (1990s-present)

- Kate Cordsen

- Christian Marclay

- Catherine Jansen

- Mike Ware

- Annie Lopez

- Azul Loeve

- Jim Read

- Hugh Scott-Douglas

- Wu Chi-Tsung

- Dan Estabrook

References

- Ware, Mike (2014). Cyanomicon. Buxton: www.mikeware.co.uk.

- Anderson, Christina, Z. (2019). Cyanotype: The Blueprint in Contemporary Practice. New York: Focal Press. pp. 11–18. ISBN 978-0-429-44141-7.

- Ford, Colin. (1988). You press the button we do the rest : the birth of snapshot photography. D. Nishen Pub. OCLC 507245621.

- Fineman, Mia (October 2004). "Kodak and the Rise of Amateur Photography". The Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Maimon, Vered, author. Singular images, failed copies : William Henry Fox Talbot and the early photograph. ISBN 978-1-4529-5352-6. OCLC 1065707839.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Burns, Nancy (2016). Cyanotypes: Photography's Blue Period. Worcester: Worcester Art Museum. ISBN 978-0-936042-06-0.

- Thornthwaite, W. H. (1851). Guide to Photography. London: Horne, Thornthwaite and Wood. OCLC 316441617.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- SCHAAF, LARRY J. (2018). SUN GARDENS : the cyanotypes of anna atkins. PRESTEL ART. ISBN 3-7913-5798-0. OCLC 1022211977.

- Atkins, Anna (1842). British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions. Britain. ISBN 978-3-95829-510-0.

- Atkins, Anna, 1799–1871. (1985). Sun gardens Victorian photograms. Aperture. ISBN 0-89381-203-X. OCLC 724532737.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Saska, Hope (2010). "Anna Atkins: Photographs of British Algae". Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts. 84 (1–4): 8–15. doi:10.1086/dia23183243. ISSN 0011-9636.

- "Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2020-02-12.

- Loos, Ted (2016-02-05). "Cyanotype, Photography's Blue Period, Is Making a Comeback". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- "Anna Atkins Refracted: Contemporary Works". www.nypl.org. September 28, 2018. Retrieved 2020-02-14.