Cyclone Hamish

Severe Tropical Cyclone Hamish was a powerful tropical cyclone that caused extensive damage to the Great Barrier Reef and coastal Queensland, Australia, in March 2009. The eighth named storm of the 2008–09 Australian region cyclone season, Hamish developed out of an area of low pressure on 4 March near the Cape York Peninsula. The storm rapidly developed into a Category 1 cyclone on the Australian intensity scale the next day. On 6 March, an eye developed, and Hamish strengthened into a Category 3 cyclone. Deep convection developed around the eye, fueling further intensification, which allowed the storm to become a Category 5 tropical cyclone late on 7 March. Hamish made its closest approach to land on 8 March, but continued moving southeastward. Eventually, the cyclone weakened and turned back towards the northwest, weakening into a remnant low on 11 March, before finally dissipating on 14 March.

| Category 5 severe tropical cyclone (Aus scale) | |

|---|---|

| Category 4 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

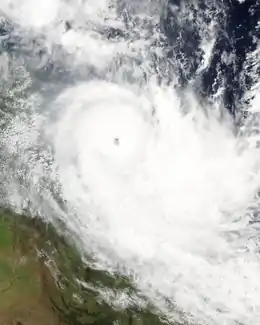

Cyclone Hamish near peak intensity on 7 March | |

| Formed | 4 March 2009 |

| Dissipated | 14 March 2009 |

| (Remnant low after 11 March) | |

| Highest winds | 10-minute sustained: 215 km/h (130 mph) 1-minute sustained: 250 km/h (155 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 924 hPa (mbar); 27.29 inHg |

| Fatalities | 2 direct |

| Damage | $38.8 million (2009 USD) |

| Areas affected | Queensland |

| Part of the 2008–09 Australian region cyclone season | |

Meteorological history

Severe Tropical Cyclone Hamish was first identified on 4 March 2009 by the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM), as a tropical low over the Coral Sea. Drifting westward, the system steadily became better defined,[1] developing convective banding features later that day. Situated in an area favouring tropical cyclone development, characterised by warm waters, low wind shear and upper-level diffluence, the low was able to quickly strengthen.[2] On the following day, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) issued a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert as convection wrapped around the centre of circulation and an anticyclone developed over the system, allowing for good outflow.[3] Hours later, the BoM classified the low as Tropical Cyclone Hamish as the storm began to moved southward in response to a mid-level ridge situated to the east.[1][4] Shortly thereafter, the JTWC also began monitoring Hamish as a tropical storm.[5]

Not long after being classified a tropical cyclone, Hamish began to undergo rapid intensification, quickly becoming a severe tropical cyclone, a storm with winds exceeding 120 km/h (75 mph), on 6 March.[1] Deep convection continued to develop around a well-defined low pressure centre, allowing for further strengthening.[6] Additionally, satellite images depicted that an eye had begun developing within the storm. A steady south-easterly track was fully established by this time as the ridge to the east and a trough over central Australia prevented westward movement.[7] Based on radar observations, the eye of Hamish was about 28 km (17 mi) in diameter by 7 March.[8] Later that day, the storm further intensified into a Category 5 cyclone on the Australian intensity scale, becoming the first to do so since Cyclone George in 2007. Later that day, Hamish attained its peak intensity with winds of 215 km/h (130 mph) along with a barometric pressure of 924 mbar (hPa; 27.29 inHg).[1][9] At the same time, the JTWC assessed the storm to have nearly become a Category 5 equivalent on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale; peak one-minute sustained winds were estimated at 250 km/h (155 mph).[5]

.jpg.webp)

At its peak, Hamish was a small cyclone;[10] gale-force winds covered an area roughly 440 km (270 mi) wide and the radius of outermost closed isobar was about 260 km (160 mi).[11] After maintaining Category 5 status for roughly 24 hours,[1] Hamish began to weaken as the interaction with coastal Australia and increased wind shear took their toll.[12] Late on 8 March, an eyewall replacement cycle had begun to take shape,[13] allowing the storm to maintain Category 4 intensity for the following few days.[1] By 10 March, the storm finally began to show signs of steady weakening as shear continued to increase due to an approaching trough from the west.[14] Later that day, the storm began to slow as it moved within a region of light steering currents. Substantial loss of convection took place during this time,[15] causing Hamish to weaken below severe tropical cyclone status by 11 March.[1]

Convection failed to redevelop over the centre of Hamish throughout 11 March, prompting the JTWC to issue their final advisory on the system.[16] The BoM also declared Hamish a remnant low around the same time; however, they continued to monitor the remnant system as it began to turn towards the northwest due to a ridge south of the storm.[17][18] The remnants of Hamish tracked in an erratic, north-westward direction over the next few days, backtracking over where it had been days earlier. The system finally dissipated on 14 March off the coast of Australia, never having made landfall.[5]

Preparations

.jpg.webp)

Following the formation of Hamish as a tropical low on 4 March, a Cyclone Watch was issued for areas between Cape Melville and Bowen.[19] Early the next morning, a Cyclone Warning was declared for areas between Cape Melville and Cardwell and the watch was extended to Hayman Island[20] and later to Mackay[21] and St Lawrence.[22] As Hamish travelled parallel to the coastline, the watches and warnings shifted towards the south, with the warnings between Cape Melville and Cape Flattery being cancelled during the afternoon of 6 March. New Cyclone Warnings were issued for areas between Cape Flattery and Lucinda.[23] Due to heavy rains produced by the outer bands of the cyclone, Flood Warnings were issued for areas between Cooktown and Townsville.[24]

On 7 March, Queensland Premier Anna Bligh signed a Declaration of Disaster Situation which permitted Australian officials to evacuate residents from the areas most at risk from Cyclone Hamish.[25] People were advised to take every action necessary to prepare for the storm and be ready to evacuate on short notice.[26] Although in the direct path of Hamish, no evacuations took place on Hayman Island. The 3,000 residents and tourists on Hamilton Island were advised to have the preparations complete by nightfall.[27] Most of the boats on the island were removed from the water in attempts to protect them from rough seas.[28] Non-essential staff and tourists were evacuated from the small resort islands of South Molle Island and Long islands.[29] in the Whitsundays to shelters located on larger islands.[27] A state of emergency was also declared for several coastal areas.[30] On 8 March, an estimated 1,000 tourists were evacuated from Fraser Island and more evacuations also took place on Lady Elliot Island and Heron Island.[31] Trains leaving Brisbane and Cairns were cancelled due to the storm for several days.[32]

Impact

As a tropical low, Hamish produced heavy rains over Far north Queensland, amounting to at least 300 mm (12 in) in localised areas. Cairns, located along the periphery of the storm, recorded 92 mm (3.6 in).[33] Between 10am and 2pm local time on 7 March, Mackay recorded 148 mm (5.8 in) of rain.[27] An additional 136 mm (5.3 in) fell the following day.[34] In combination with high tide, Hamish produced a 6.3 m (20.6 ft) tide in Mackay, flooding some streets. No injuries were reported due to the flooding but debris was washed out to sea.[35] An estimated 2,000 residents were left without power along the south-east coast of Queensland.[36] The rough seas produced by the storm severely injured a member of the coast guard during his patrol around Noosa.[37]

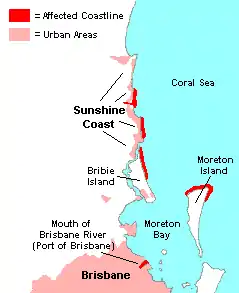

A 4.5 m (14.7 ft) tide flooded parts of Yeppoon, but no major damage was reported.[38] Officials in Mackay estimated that damages would total in the tens of thousands.[39] The Sunshine Coast in Queensland sustained significant beach erosion and at least 30 trees were knocked down. A pier sustained damage and another was partly destroyed.[40] Severe erosion on Bribie Island and further erosion could create a break in the island, creating a passage to the Pumicestone Passage. The Golden Beach Progress Association chairman, Mick Graham, feared that if this happened, the structure of the island and passage would change.[41] On the Discovery Coast, constant beach erosion washed away numerous trees and some walkways, with officials estimating that millions of tonnes of debris were in the water.[42]

A trawler caught in rough seas produced by the storm sent out a distress signal as it became overcome by the storm. Rescue attempts to retrieve the three crew members were hampered by Hamish and were called off but expected to resume of 10 March.[43] Nearly three days following the sinking of the trawler, officials called off the search and presumed that the two missing fishermen had drowned after finding empty life jackets and an un-deployed life raft.[44] Severe erosion also caused the northern part of Fraser Island to become nearly inaccessible as it left the bedrock exposed. The Environmental Protection Agency stated that it was possible for light vehicles to continue along the normal route during low tide but were recommended to take the two-hour detour.[45] Throughout the Queensland coastline, damage from Hamish amounted to A$60 million (US$38.8 million).[46]

Great Barrier Reef

Along the storm's 500 km (310 mi) track parallel to the Queensland coastline, the eye passed over a substantial portion of the Great Barrier Reef, resulting in some of the worst damage to the area in recent history. Unlike most cyclones which travel from east to west in the region, impacting only a small area of the reef, Hamish moved alongside the reef for nearly its entire existence. The Bureau of Meteorology estimated that about a quarter of the area was impacted by the storm, with some parts being within 30 km (19 mi) of Hamish's eye when it was a Category 5 cyclone. According to post-storm surveys of the reef, the damage done to the coral was extensive, with upwards of 70% losses in the hardest hit spots. Nearly all of the exposed coral was destroyed by turbulent waters; however, in places where the coral was slightly sheltered, there was little to no damage. Some areas were completely stripped of all living tissues, leaving only bare limestone. According to preliminary estimates, it would take the reef between eight and fifteen years to recover from Hamish if nothing hampers growth.[47]

The Swain sector of the Great Barrier Reef, once considered one of the most densely coral-populated regions of the reef, was almost completely destroyed by the storm. Research times found little in the way of coral remaining on exposed surfaces.[48] Due to the severity of the damage, the Queensland Seafood Industry Association requested that the reef be declared a disaster zone between Bowen and Wide Bay. Fish previously living in the area were no longer present by 25 March. Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority chairman Russel Reicheld stated that "Hamish did more damage to the reef than any other natural disaster in recent history."[49]

Oil spill

A 183 m (600 ft) cargo ship called the MV Pacific Adventurer was carrying 60 containers of ammonium nitrate when it encountered rough seas produced by Hamish, while located about 13 km (8 mi) east of Cape Moreton.[50] The incident occurred near to a marine animal park, which is home to endangered species.[51] Around 3:15 a.m. EST on 11 March 31 of the containers spilled into the sea along with a large amount of heavy fuel, causing the surface of the water to become slick.[50] Officials attempted to contain the oil spill, but the rough seas prevented easy containment. Environmentalist warned that the oil could have a significant impact on the local wildlife.[52] One of the containers damaged the hull as it fell off the ship.[53] After divers inspected the ship for the source of the spill, two holes were found. One, located just above the waterline, was 10 mm (0.4 in) long 15 mm (0.6 in) wide. The second and larger hole was located underneath the ship. The length of it was about 1 m (1.3 ft) and the width was 300 mm (11.8 in).[54]

An estimated 620 tonnes of ammonium nitrate[55] and 250 tonnes of fuel spilled out of the ship.[56] The spilled fuel initially covered an area about 5.5 km (3.4 mi) long and 500 m (1,600 ft) wide. Although ammonium nitrate is not harmful to the environment, the high concentration was proposed to have the capability of suffocating marine life in the area.[51] The oil spill continued to expand in coverage, affecting five beaches and forcing several other beach areas to shut down.[57] By 13 March, the oil covered an estimated 40 km (25 mi) of coastline and was several centimetres thick in places. The coverage and depth of the spill led Anna Bligh to state that the crew members of the ship were likely understating the amount of fuel that leaked out.[58][59]

Aftermath

Health officials hoped that rains from Hamish would help to reduce an ongoing dengue fever outbreak; however, little rainfall reached the coast, allowing further growth of the disease.[60] On 10 March—following improved weather—rescue teams resumed searching for the three missing fishermen. During the second rescue attempt, one of the fishermen was found alive but alone in a large swell about 259 km (161 mi) northeast of Yeppoon, Queensland.[61] The rescuers were able to find him when he turned on an Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon, which he originally thought was a stick. This beacon allowed the rescuers to pinpoint his location, though the other two fishermen reportedly did not have these beacons.[62] On 16 March, a memorial service was held for the two fishermen who were lost at sea. About 200 people who knew the two men attended the service; many of whom signed a book honoring the fishermen.[63]

Following the oil spill, Queensland Premier Anna Bligh declared two islands and parts of the Sunshine coast as disaster areas.[58] Cleanup efforts were reportedly going to cost at least $100,000 a day and last more than a week as the oil continued to spread. The company in charge of the cargo ship is faced with a possible $1.5 million in fines for the incident. Several search parties have been sent to the spill area to attempt to find the potentially explosive materials that were in the 31 containers. Press reports stated that if the ammonium nitrate were to mix with the heavy fuel, it could ignite the ammonium nitrate and cause a large explosion. If the chemical did not react with the fuel, but still leaked out, marine life could be threatened by large blooms in algae.[64] A team of 88 people were sent out to begin the cleanup process and another 58 were expected to join within the following days.[59] On Moreton Island, a total of 290 people are working to clean up the oil with most of them focusing on Middle Creek and Cape Moreton.[56] Even though hundreds of people were working on cleaning the spill, the average amount cleaned each day was 1 km2 (0.6 mi2).[65] It was not until May of that year that Moreton Island was finally cleared of oil. The cleanup effort was undertaken by 2,500 people and led to the removal of roughly 3,000 tonnes of contaminated sand.[66]

The estimated cost to clean the island was put at A$5 million (US$3.2 million).[67] Following the environmental disaster, the company is being fined an additional A$248.6 million (US$163.5 million).[68] In July 2010, the captain of the vessel which spilled the oil was brought to court on charges of disposing oil in coastal waters.[69] In light of the worldwide infamy the ship received, a commercial decision was made by the Swire shipping company to rename the cargo ship the MV Pacific Mariner.[70]

In June 2009, the name Hamish was retired from the list names in the Australian Basin; it was later replaced with Herman.[71]

See also

- Timeline of the 2008–09 Australian region cyclone season

- Cyclone Oswald

References

- "Severe Tropical Cyclone Hamish". Bureau of Meteorology. 2010. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (4 March 2010). "Significant Tropical Weather Outlook". Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command. Archived from the original on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (5 March 2009). "Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert". Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (5 March 2009). "Tropical Cyclone 18P (Hamish) Advisory One". Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (2010). "Tropical Cyclone 18P (Hamish) Best Track" (TXT). Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (6 March 2009). "Tropical Cyclone 18P (Hamish) Advisory Two". Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command. Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- "Severe Tropical Cyclone Hamish Technical Bulletin- 1200 UTC 6 March 2009". Bureau of Meteorology. 6 March 2009. Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (7 March 2010). "Tropical Cyclone 18P (Hamish) Advisory Four". Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command. Archived from the original on 7 March 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- "Database of Past Australian Tropical Cyclone Tracks" (.CSV). Bureau of Meteorology. 7 December 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (2010). "Frequently Asked Questions: What is the average size of a tropical cyclone?". Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- "Severe Tropical Cyclone Hamish Technical Bulletin 1800UTC 7 March 2009". Bureau of Meteorology. 7 March 2009. Archived from the original on 7 March 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (8 March 2009). "Tropical Cyclone 18P (Hamish) Advisory Six". Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command. Archived from the original on 10 March 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- "Severe Tropical Cyclone Hamish Technical Bulletin 1200UTC 8 March 2009". Bureau of Meteorology. 8 March 2009. Archived from the original on 8 March 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (10 March 2009). "Tropical Cyclone 18P (Hamish) Advisory Ten". Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command. Archived from the original on 10 March 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (11 March 2009). "Tropical Cyclone 18P (Hamish) Advisory Twelve". Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center (11 March 2010). "Tropical Cyclone 18P (Hamish) Advisory Fourteen (Final)". Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command. Archived from the original on 12 March 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- "Tropical Cyclone Hamish Technical Bulletin 0600UTC 11 March 2009". Bureau of Meteorology. 11 March 2009. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- "Ex-Tropical Cyclone Hamish Technical Bulletin 1200UTC 11 March 2009 (Final)". Bureau of Meteorology. 11 March 2009. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- "Tropical Cyclone Advice Number 1". Bureau of Meteorology. 5 March 2009. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- "Tropical Cyclone Advice Number 3". Bureau of Meteorology. 6 March 2009. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- "Tropical Cyclone Advice Number 4". Bureau of Meteorology. 6 March 2009. Archived from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- "Tropical Cyclone Advice Number 5". Bureau of Meteorology. 6 March 2009. Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- "Tropical Cyclone Advice Number 7". Bureau of Meteorology. 6 March 2009. Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- "Tropical Cyclone Advice Number 8". Bureau of Meteorology. 6 March 2009. Archived from the original on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- Staff Writer (7 March 2009). "Nth Qld on high alert as Hamish approaches Cat 5". ABC News. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- Shani Raja (7 March 2009). "Australian Resorts in Queensland Threatened by Cyclone Hamish". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- Samantha Healy (7 March 2009). "Cyclone Hamish could be worse than Cyclone Larry". Queensland Newspapers. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- Staff Writer (7 March 2009). "Bligh declares disaster situation as Hamish intensifies". ABC News. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- Associated Press (7 March 2009). "Menacing cyclone forces island evacuations". The Age. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- Staff Writer (7 March 2009). "NE Australia bracing for tropical cyclone". Radio Netherlands. Archived from the original on 2 May 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- Xinhua (8 March 2009). "Fraser island evacuated as cyclone hits Australia". China View. Retrieved 8 March 2009.

- Cassie White (9 March 2009). "Cyclone Hamish hampers rail services". ABC News. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- Staff Writer (7 March 2009). "Whitsundays expected to bear brunt of Hamish". ABC News. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- Sarah Crawford (9 March 2009). "Mackay Hamish warning cancelled". Daily Mercury. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- Bianca Clare (9 March 2009). "Hamish's ads height to mackay's king of the tides". Daily Mercury. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- Staff Writer (10 March 2009). "Weakening cyclone Hamish continues to batter southern Qld". ABC News. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- Mike Garry (16 March 2009). "Coast Guard rocked by Hamish". Sunshine Coast Daily. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- Sharyn O'Neill (10 March 2009). "Hamish's worst effects offshore". The Bulletin. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- Bianca Clare (11 March 2009). "Hamish's hammer blows test marina". Daily Mercury. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- Amy Remeikis (11 March 2009). "Hamish hurts Sunshine Coast beaches". Sunshine Coast Daily. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- Staff Writer (11 March 2009). "Fears Hamish could submerge Bribie's tip". ABC News. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- Rob Black (11 March 2009). "Huge waves wash away sand dunes". The Observer. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- AAP (9 March 2009). "Fears for trawler crew in cyclone area". The Australian. Archived from the original on 12 March 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- AAP (13 March 2009). "Search for fishermen called off". Brisbane Times. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- Katerine Spackman (16 March 2009). "Erosion creates Fraser Is access uncertainty". ABC News. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- Alan Lander (7 May 2009). "Council to tether waterfront assets". Sunshine Coast Daily. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- Sara Trenerry and Wendy Ellery (20 August 2009). "Research reveals cyclone's ravages on the Reef". In Sciences Organization. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- Michelle Jonker (23 October 2009). "Report on reefs in the Swains sector of the Great Barrier Reef". Australian Institute of Marine Science. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- Sarah West (25 March 2009). "Cyclone Hamish reef damage 'worst in 30 years'". ABC News. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- Staff Writer (11 March 2009). "Ship spills chemicals in waters off Australia". Cable News Network. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- Staff Writer (11 March 2009). "Australian ship spills fertiliser near marine sanctuary". AFP. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- Staff Writer (11 March 2009). "Fuel oil spills from Australian ship". United Press International. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- Marissa Calligeros (11 March 2009). "Oil spills from cargo ship into Moreton Bay". Brisbane Times. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- AAP (15 March 2009). "Government says it has oil spill under control". The Age. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- Staff Writer (11 March 2009). "Cyclone oil spill threatens wildlife". World News Australia. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- Andrew Wight (15 March 2009). "Clean-up efforts continue". Brisbane Times. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- Bonnie Malkin (12 March 2009). "Australians rush to clean up oil slick threatening marine life". Telegraph. Retrieved 12 March 2009.

- Angela Macdonald-Smith (13 March 2009). "Australia's Queensland Declares Disaster as Oil Coats Beaches". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- Christine Kellett (13 March 2009). "Oil slick puts Moreton Island drinking water at risk". Brisbane Times. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- Marissa Calligeros (9 March 2009). "Cyclone heightens dengue fears". Brisbane Times. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- Georgina Robinson (10 March 2009). "Cyclone Hamish: one fisherman found alive". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- Staff Writer (10 March 2009). "Monster wave saved me from Cyclone Hamish says fisherman". The Herald Sun. Archived from the original on 13 March 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

- Hervey Bay (16 March 2009). "Service honours lost fishermen". Fraser Coast Chronicle. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- Staff Writer (12 March 2009). "Hazardous Cargo Ship Sent Into Savage Storm". Transport and Logistics News. Archived from the original on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 12 March 2009.

- Connie Levett (15 March 2009). "Oil spill could take a month to clean". The Age. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- "Moreton Bay oil spill". Government of Queensland. 11 May 2009. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- Cosima Marriner and Connie Levett (16 March 2009). "Opposition pours oil on flames of ALP election campaign". The Age. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- Dennis Passa (14 March 2009). "'Catastrophe' fear over Australian oil spill". The Scottsman. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- Australian Associated Press (5 July 2010). "Skipper faces court over 2009 Queensland oil spill disaster". The Australian. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- Australian Associated Press (11 July 2009). "Cargo ship changes name after Sunshine Coast spill". New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- "Tropical Cyclone Names". Bureau of Meteorology. 2010. Retrieved 10 August 2009.