Cyclone Tessi

Severe Tropical Cyclone Tessi was a small but potent tropical cyclone that caused extensive damage along the coast of North Queensland in early April 2000. The ninth cyclone and fourth severe tropical cyclone of the 1999–2000 Australian region cyclone season, Tessi developed on 1 April from a persistent trough of low pressure in the Coral Sea and slowly tracked west-southwestward. Tessi was an unusually compact storm that strengthened rapidly just before landfall, peaking as a Category 3 severe tropical cyclone on the Australian tropical cyclone intensity scale with 10-minute average maximum winds of 140 km/h (85 mph). Around 22:00 UTC on 2 April, Tessi moved ashore about 75 km (45 mi) northwest of Townsville and rapidly diminished as it progressed inland. At the height of the storm, Magnetic Island experienced sustained winds of 109 km/h (68 mph), while gusts as high as 130 km/h (81 mph) were recorded in Townsville.

| Category 3 severe tropical cyclone (Aus scale) | |

|---|---|

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

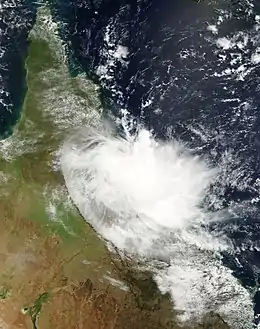

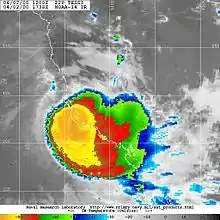

Cyclone Tessi on 3 April | |

| Formed | 1 April 2000 |

| Dissipated | 3 April 2000 |

| Highest winds | 10-minute sustained: 140 km/h (85 mph) 1-minute sustained: 95 km/h (60 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 980 hPa (mbar); 28.94 inHg |

| Fatalities | None reported |

| Damage | At least $50 million (2000 AUD) |

| Areas affected | Queensland |

| Part of the 1999–2000 Australian region cyclone season | |

Tessi's strong winds caused widespread damage along the coast from Ingham to Ayr, most notably around Townsville, where many trees were uprooted and 50,000 homes lost electricity. Buildings and vehicles were damaged by the winds and fallen trees, and roadways surrounding the city became impassable. Torrential rains, amounting to 423.4 mm (16.67 in) in just 24 hours, saturated a hillside in Castle Hill and caused a large landslide. Hundreds of Castle Hill residents were forced to leave their homes, and many structures were inundated with mud and debris. The landslide dislodged a large boulder uphill from several residences, creating a period of local concern before workers stabilised the slope. Along the coast, the storm wrecked boats and eroded beaches. Total damage in Townsville was estimated to be at least $50 million (2000 AUD), and the name Tessi was later retired due to the cyclone's impacts.

Meteorological history

Cyclone Tessi originated in a northwest–southeast oriented trough of low pressure that developed in the Coral Sea at the end of March 2000.[1] Similar conditions would lead to the genesis of Cyclone Vaughan in the same region just days later.[2] Initially forming within the trade winds east of an upper-level trough over eastern Australia, the disturbance that ultimately spawned Tessi persisted in the area for nearly a week before becoming associated with an organised area of convection on 31 March,[1][2] about 1,100 km (680 mi) east of Cooktown, Queensland.[2] At that point, the Bureau of Meteorology's (BoM) Tropical Cyclone Warning Centre in Brisbane operationally identified the system as a tropical low and began issuing gale warnings.[2] At 00:00 UTC on 2 April, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) designated the system 22S.[3] Diffluence from an anticyclone to the east promoted favourable outflow in the upper levels of the atmosphere, and a closed centre of circulation rapidly formed.[1] As the disturbance tracked southwestward around the periphery of a mid-level ridge to the south,[4] its appearance on satellite imagery continued to improve, with distinct rainbands wrapping around the centre.[2] At 18:00 UTC on 1 April, the system intensified into Tropical Cyclone Tessi while located under 500 km (310 mi) northeast of Townsville, Queensland.[5]

Tessi was an extremely small tropical system, described as a "midget cyclone," that continued to contract due to rising environmental air pressures as it approached the coast. Additionally, the storm's wind field was lopsided, with gale-force winds extending 185 km (115 mi) to the south of the centre but only 30 km (19 mi) to the north.[2] Nonetheless, the parent trough provided an area of generally weak inhibiting wind shear,[1] allowing the cyclone to quickly strengthen.[2] Around 18:00 UTC on 2 April, while Tessi was just offshore, a small eye feature only 10 km (6.2 mi) across became evident on weather radar.[2] By 20:00 UTC, the storm reached its peak intensity with 10-minute maximum sustained winds of 140 km/h (85 mph) and a minimum central air pressure of 980 mbar (28.94 inHg). This made it a Category 3 severe tropical cyclone on the Australian cyclone scale.[5] The JTWC estimated weaker 1-minute winds of 95 km/h (60 mph).[3] Shortly after peaking, Tessi made landfall just south of Lucinda, or about 75 km (45 mi) northwest of Townsville.[4][6] Land-based observations and radar imagery suggested that the storm was more intense than indicated by its satellite presentation.[2] Upon moving ashore, the cyclone slowed and rapidly deteriorated, and it dissipated by 00:60 UTC on 3 April.[3] The small cyclone's rapid strengthening before landfall was generally not well-forecast by weather models; in particular, the ECMWF model anticipated that the system would degenerate back into an open trough before moving ashore.[7]

Impact

While moving inland, Tessi produced strong winds and very heavy rainfall. Wind damage was widespread but generally of a minor nature,[4] extending from Ingham to Ayr along the coast of Queensland.[8] New daily and monthly total rainfall records were set in Townsville, where 423.4 mm (16.67 in) of rainfall was recorded in a 24-hour period. The city also experienced wind gusts as high as 130 km/h (81 mph), peaking at 15:40 UTC on 2 April,[2] while situated within the storm's left-front quadrant.[9] In and around Townsville, the powerful gusts brought down thousands of trees, some of which struck and damaged buildings and caravans. Multiple roofs sustained damage, and fallen power lines left 50,000 households without electricity.[10] By two days after the storm, only about half of the outages had been restored.[11] Many roads were damaged or obstructed by debris, leaving the city isolated for a time.[12] After Tessi weakened below the tropical cyclone threshold, its remnants continued to produce heavy rainfall. One station in the Haughton River watershed recorded more than 200 mm (7.9 in) in 12 hours on 3 April, including a maximum hourly rainfall rate of 44 mm (1.7 in). The Haughton River swelled to record levels until the small town of Giru was completely submerged with floodwaters averaging 0.7 m (2.3 ft) deep.[6][11]

To the north of Townsville, severe wind damage was reported in the small community of Mutarnee, where the cyclone uprooted numerous large trees and blew the roof of a house 60 m (200 ft) away. The most intense winds were likely confined to the sparsely populated shoreline east of Mutarnee; there, tree damage was significant, and a few beach huts were damaged.[2] Along the coast, rough seas washed ashore and wrecked several boats.[2] The Port of Townsville sustained $1.1 million in damage, which included the destruction of breakwaters.[13] Coastal installations along the Strand were also damaged by the rough seas,[14] while the onshore winds blasted tree trunks with sand from the beaches and left up to 10 cm (3.9 in) of accumulated sand in car parks. Along the coast of Rowes Bay, high waves steepened an existing erosion cliff by as much as 4 m (13 ft), although much of the removed sand was simply deposited closer to the water. Despite 2,700 m3 (95,000 cu ft) of sand being displaced from the base of the scarp, the changes to the beach were considered to be within acceptable parameters of the ongoing beach nourishment project.[9] Tessi also had a serious impact on seagrass meadows, such as those in Cockle Bay.[15] Just offshore, Magnetic Island endured 10-minute sustained winds of 109 km/h (68 mph) in what was described as its worst storm in 30 years.[10] Streets on the island were littered with debris,[12] and residents were left with limited supplies of drinking water.[11]

The torrential rainfall caused extensive flash flooding and triggered a large landslide in a residential neighbourhood in Castle Hill, a suburb of Townsville.[2] The landslide comprised four distinct debris flows, totalling about 2,000 m3 (71,000 cu ft) of weathered granite plunging downhill.[16] Two homes were destroyed while many others were invaded by large volumes of mud and debris.[10] A mansion belonging to the owner of the Townsville Crocodiles was among the most severely impacted properties, being almost entirely buried under the landslide. Around 400 residents of the community were forced to evacuate nearly 140 homes,[12][17] and 10 individuals were hospitalised with acute stress.[10] With fears of additional rainfall from Cyclone Vaughan, dozens of engineers rushed to secure a large 6 m (20 ft), 150-tonne boulder that the landslide dislodged and left resting precariously on the hillside above several homes.[10][18] After workers spent more than 24 hours reinforcing the boulder and removing other loose debris from the hillside, the immediate threat was alleviated.[18] However, concerns about the stability of the slope and disputes over the funding necessary for ongoing maintenance still lingered as of 2012.[19] As the landslide occurred in an affluent neighbourhood,[2] some residents feared the incident would lower their property values.[18] In addition to the Castle Hill landslide, Tessi's rainfall induced smaller rock falls and debris flows throughout susceptible areas of Townsville.[20]

Aftermath

During and after the storm, the State Emergency Service responded to 530 calls for assistance.[10] While attempting to repair a damaged power line, two Queensland Rail workers received electrical shocks, with one of them being severely injured.[21] As emergency workers were preoccupied with the aftermath of Tessi, burglars looted 80 homes and businesses, as well as flooded vehicles and damaged yachts, in Townsville.[22][23] In the aftermath of the cyclone, some 400 Townsville City Council workers embarked on clean-up efforts.[10] Vegetation debris in Townsville was collected and processed into 25,000 m3 (880,000 cu ft) of mulch,[24] which was used in local botanical gardens like The Palmetum.[25] By 6 April, local insurers had received 3,000 claims for property damage.[26] Townsville mayor Tony Mooney initially estimated damage to private property from Tessi at $100 million, and judged the destruction more severe than that of the 1998 Townsville floods.[11] Later, a post-storm assessment placed the damage total closer to $50 million.[27] After the season ended, the name Tessi was retired from the Australian tropical cyclone naming list due to the cyclone's "negative impact."[28]

References

- Bonell, M. and Bruijnzeel, L. A. (2005). Forests, Water and People in the Humid Tropics: Past, Present and Future Hydrological Research for Integrated Land and Water Management. Cambridge University Press. p. 216. ISBN 1139443844. Retrieved 26 February 2017.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Padgett, Gary (4 January 2007). "Monthly Global Tropical Cyclone Summary: April, 2000". Australian Severe Weather. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- "SH22 best track". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- "Tropical Cyclone Tessi: 1 – 2 April 2000". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- "The Australian Tropical Cyclone Database" (CSV). Australian Bureau of Meteorology. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

- Baddiley, Peter and Malone, Terry (5 April 2000). "Haughton River Flood: April 2000" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 27 February 2017.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Callaghan, Jeff. "Present and Future Uses of Satellite Observations for Tropical Cyclone Forecasting and Research". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- "Cyclone's trail of turmoil". The Advertiser. 4 April 2000. p. 7.

- Mabin, M. C. G. (June 2000). "Rows Bay – Pallarenda Foreshore Response to Cyclone Tessi 3 April 2000" (PDF). Townsville City Council. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Lawlor, Ali (8 April 2000). "North reels from week of woe". The Courier-Mail. p. 12.

- Lawlor, Ali (5 April 2000). "Heartbreak hill braces for second cyclone". The Courier-Mail. p. 1.

- "Landslide wrecks homes". Herald Sun. 4 April 2000. p. 2.

- "Cyclone Damage, Townsville". Cullen, Grummitt and Roe. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- "150 Years of Townsville Series: Part 3 Natural Disasters". Townsville Bulletin. 20 October 2015. p. 22.

- "Townsville". Seagrass-Watch. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Leiba, Marion (January 2013). "Impact of landslides in Australia to December 2011". The Australian Journal of Emergency Management. 28 (1). Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- "Landslip forces 400 from homes". The Daily Telegraph. 5 April 2000. p. 10.

- Pullman, Francine (9 April 2000). "Steady as a rock...". The Sunday Mail. p. 23.

- Skene, Kathleen (3 March 2012). "Hill-slide living Landslip threat hangs over residents". Townsville Bulletin. p. 1.

- Natural Disaster Risk Management Study Contract T5631: Landslide Hazard Study (PDF) (Report). Townsville City Council. 31 August 2011. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Thomas, Shelley (6 April 2000). "Probe into powerline accident". The Courier-Mail. p. 7.

- "Cyclone looters 'scum'". The Daily Telegraph. 6 April 2000. p. 14.

- Roberts, Greg. "Looters rampage in cyclone's wake". The Age. p. 10.

- Tyrell, Les (17 February 2011). "City's amazing fightback". Townsville Bulletin. p. 16.

- "Newsletter of the Association of Friends of Botanic Gardens (Victoria) Inc" (PDF) (15). Association of Friends of Botanic Gardens. October 2000: 8. Retrieved 27 February 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Lawlor, Ali (7 April 2000). "Boulder at bay as city braces for flooding". The Courier-Mail. p. 2.

- Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. "EM-DAT: The Emergency Events Database". Université catholique de Louvain.

- RA V Tropical Cyclone Committee (8 October 2020). Tropical Cyclone Operational Plan for the South-East Indian Ocean and the Southern Pacific Ocean 2020 (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. pp. I-4–II-9 (9–21). Retrieved 10 October 2020.