David Unaipon

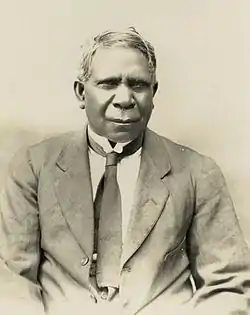

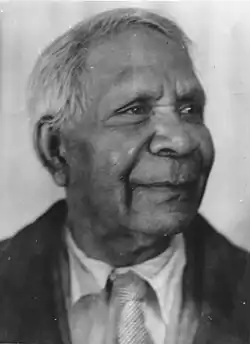

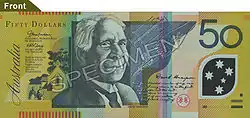

David Unaipon (born David Ngunaitponi) (28 September 1872 – 7 February 1967) was an Aboriginal Australian man[2] of the Ngarrindjeri people, a preacher, inventor and author. Unaipon's contribution to Australian society helped to break many Aboriginal Australian stereotypes, and he is featured on the Australian $50 note in commemoration of his work. He was the son of preacher and writer James Unaipon.

David Ngunaitponi David Unaipon (Anglicisation) | |

|---|---|

Unaipon in the late 1920s | |

| Born | David Ngunaitponi 28 September 1872 Point McLeay Mission, South Australia, Australia |

| Died | 7 February 1967 (aged 94) Tailem Bend, South Australia, Australia |

| Nationality | |

| Education |

|

| Spouse(s) | Katherine Carter (née Sumner) |

| Parent(s) |

|

Biography

Born at the Point McLeay Mission on the banks of Lake Alexandrina in the Coorong region of South Australia, Unaipon was the fourth of nine children of James and Nymbulda Ngunaitponi, of the Portaulun branch of the Ngarrindjeri people. Unaipon began his education at the age of seven at the Point McLeay Mission School and soon became known for his intelligence, with the former secretary of the Aborigines' Friends' Association stating in 1887: "I only wish the majority of white boys were as bright, intelligent, well-instructed and well-mannered, as the little fellow I am now taking charge of."[2]

Unaipon left school at 13 to work as a servant for C.B. Young in Adelaide where Young actively encouraged Unaipon's interest in literature, philosophy, science and music. In 1890, he returned to Point McLeay where he apprenticed to a bootmaker and was appointed as the mission organist.[3] In the late 1890s he travelled to Adelaide but found that his colour was a bar to employment in his trade and instead took a job as storeman for an Adelaide bootmaker before returning to work as book-keeper in the Point McLeay store.

On 4 January 1902 he married Katherine Carter (née Sumner), a Tangane woman.[4] He was later employed by the Aborigines' Friends' Association as a deputationer, in which role he travelled and preached widely in seeking support for the Point McLeay Mission.[5] Unaipon retired from preaching in 1959 but continued working on his inventions into the 1960s.[4]

Inventor

Unaipon spent five years trying to create a perpetual motion machine. In the course of his work he developed a number of devices.[6] He was still attempting to design such a device in his seventy-ninth year.[7]

Unaipon took out provisional patents for 19 inventions but was unable to afford to get any of his inventions fully patented, according to some sources. Muecke and Shoemaker say that between "1910 and 1944 he made ten ... applications for inventions as varied as an anti-gravitational device, a multi-radial wheel and a sheep-shearing handpiece".[8][9] Provisional patent 15,624 which he ratified in 1910, is for an "Improved mechanical motion device"[10] that converted rotary motion which "is applied, as for instance by an Eccentric",[11] into tangential reciprocating movement, an example application given being sheep shears. The invention, the basis of modern mechanical sheep shears, was introduced without Unaipon receiving any financial return and, apart from a 1910 newspaper report acknowledging him as the inventor, he received no contemporary credit.[6]

Other inventions included a centrifugal motor, a multi-radial wheel and a mechanical propulsion device. He was also known as the Australian Leonardo da Vinci for his mechanical ideas, which included pre World War I drawings for a helicopter design based on the principle of the boomerang and his research into the polarisation of light and also spent much of his life attempting to achieve perpetual motion.[12]

Writer and lecturer

Unaipon was obsessed with correct English and in speaking tended to use classical English rather than that in common usage. His written language followed the style of John Milton and John Bunyan.[5]

Unaipon was the first Aboriginal author to be published after he was commissioned in the early 1920s by the University of Adelaide to assemble a book on Aboriginal legends. From 1924 onwards he also wrote numerous articles for the Sydney Daily Telegraph. He published three short booklets of Aboriginal stories in 1927, 1928 and 1929. In this time he wrote on topics covering everything from perpetual motion and helicopter flight to Aboriginal legends and campaigns for Aboriginal rights.[13]

Unaipon was inquisitively religious, believing in an equivalence of traditional Aboriginal and Christian spirituality. His employment with the Aborigines' Friends' Association collecting subscription money allowed him to travel widely. The travel brought him into contact with many intelligent people sympathetic with the cause of Aboriginal rights, and gave him the opportunity to lecture on Aboriginal culture and rights. He was much in demand as a public speaker.

Many times he was refused accommodation due to his race. He said "...in Christ Jesus colour and racial distinctions disappear..." and that this thought helped him at such times.[14]

Unaipon was the first Aboriginal writer to publish in English,[15] the author of numerous articles in newspapers and magazines, including the Sydney Daily Telegraph, retelling traditional stories and arguing for the rights of Aboriginal people.

Five of Unaipon's traditional stories were published in 1929 as Native Legends, under his own name and with his picture on the cover.[16]

Some of Unaipon's traditional Aboriginal stories were published in a 1930 book, Myths and Legends of the Australian Aboriginals, under the name of anthropologist William Ramsay Smith.[9] They have been republished in their original form, under the author's name, as Legendary Tales of the Australian Aborigines.[17]

Further work

He was a recognised authority on ballistics.[6]

Unaipon was also involved in political issues surrounding Aboriginal affairs and was a keen supporter of Aboriginal self-determination, including working as a researcher and witness for the Bleakley Enquiry into Aboriginal Welfare and lobbied the Australian Government to take over responsibility for Aboriginals from its constituent states. He proposed to the government of South Australia to replace the office of Chief Protector of Aborigines with a responsible board and was arrested for attempting to provide a separate territory for Aboriginals in central and northern Australia.

In 1936, he was reported to be the first Aboriginal to attend a levée, when he attended the South Australian centenary levée in Adelaide, an event that made international news.[18]

Unaipon's stance on Aboriginal issues put him into conflict with other Aboriginal leaders, including William Cooper of the Australian Aborigines' League, and Unaipon publicly criticised the League's "Day of Mourning" held on the 150th anniversary of the arrival of the First Fleet, arguing that the protest would only harm Australia's reputation abroad and would cement a negative public opinion of Aboriginals.[19]

Award

Unaipon was awarded a Coronation medal in 1953 at the age of 81 celebrating the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II and received the FAW Patricia Weickhardt Award for Aboriginal writers in 1985 after his death.

Personal life

Unaipon was a very influential man during his era, but was often refused accommodation because of his race.[13]

Later life

Unaipon returned to his birthplace in his old age, where he worked on inventions and attempted to reveal the secret of perpetual motion. A member of the Portaulun (Waruwaldi) people.[1]

Death

Unaipon died in the Tailem Bend Hospital on 7 February 1967 and was buried in the Raukkan (formerly Point McLeay) Mission Cemetery.[4] He was survived by a son.

Legacy and tributes

- An interpretive dance based on Unaipon's life, Unaipon, was performed by the Bangarra Dance Theatre.[20]

- The David Unaipon Literary Award established in 1988 is an annual award presented for the best of writing of the year by unpublished Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander authors.[21][13]

- The David Unaipon College of Indigenous Education And Research at the University of South Australia is named after him.[22]

- Unaipon Avenue in the Canberra suburb of Ngunnawal is named after him.[23]

- In 1985 he was posthumously awarded the Fellowship of Australian Writers' FAW Patricia Weickhardt Award to an Aboriginal Writer.[24]

- The annual Unaipon lecture in Adelaide was established in 1988.[23][4][25]

- Also in 1988, the national David Unaipon Award for Aboriginal Writers was established.[4]

Fifty-dollar note

The background features the Raukkan mission and Unaipon's mechanical shearer.

Allan "Chirpy" Campbell, reported to be a great-nephew of David Unaipon, failed in an attempt to negotiate a settlement with the Reserve Bank of Australia for using an image of Unaipon on the Australian $50 note without the permission of the family. Campbell's argument was that the woman (who had since died) originally consulted by the Reserve Bank was not related to Mr Unaipon.[26] Campbell was seeking A$30 million in compensation, plus ten years legal fees, plus a number of non-monetary items. The request for compensation was turned down. Campbell later claimed compensation from eBay, which used images of the Australian notes in an advertising campaign.

Works

- Unaipon, David. Legendary Tales of the Australian Aborigines. Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84905-9.

- Volume 1 Manuscript of Legendary Tales of Australian Aborigines' by David Unaipon, 1924–1925, acquired with the Publishing Archive of Angus & Robertson in 1933 by the State Library of New South Wales

- Volume 2 Typescript of Legendary Tales of Australian Aborigines' by David Unaipon, 1924–1925, acquired with the Publishing Archive of Angus & Robertson in 1933 by the State Library of New South Wales

- 8. Unaipon, David, 1925–1927, Volume 85 Item 2: Angus & Robertson correspondence files from Lilian Irene Turner to Arthur Styles Vallack, 1896–1931, acquired with the Publishing Archive of Angus & Robertson in 1933 by the State Library of New South Wales

- Aboriginal legends (Hungarrda) by David Unaipon, 1924–1925, published by Adelaide: S.n, State Library of New South Wales, 398.20994/41

See also

Notes

- The only primary source for the name Nymbulda is George Taplin. The Yaraldi genealogy compiled by Ronald Berndt names her as Nymberindjeri with Nymbulda being her father's first wife, and there was also another of that name married to another relative. It cannot be ruled out that she was known by both names. Aboriginal tradition required that after a death, the deceased person's name could no longer be used and those with the same name would take a new name (Berndt, Berndt & Stanton 1993, pp. 515–516)

Citations

- Tindale 1974, p. 217.

- Jenkin 1979, p. 185.

- HToSA.

- AuDB 1990.

- Harris 2004.

- Jenkin 1979, pp. 234–236.

- Hosking 1995, p. 89.

- Unaipon, Muecke & Shoemaker 2001, p. xvi.

- Miller 2005, p. ?.

- AusPat 1909.

- Aus. Pat 15624

- ABC 2009.

- Australian Geographic 2014.

- Hosking 1995, p. ?.

- Gale 1997, p. 41.

- Hosking 1995, p. 94.

- Unaipon, Muecke & Shoemaker 2001.

- The Times 1936, p. 15.

- Attwood & Marcus 2004, pp. 86–88.

- Whitehorn 2010, p. 16.

- The Australian.

- David Unaipon College.

- Unaipon Avenue.

- AustLit.

- PSA 2018.

- Statham 2008.

Sources

- Attwood, Bain; Marcus, Andrew (2004). Thinking Black: William Cooper and the Australian Aborigines League. Aboriginal Studies Press. ISBN 978-0-855-75459-4.

- "Australian Aboriginal at Leveé". The Times. London. 24 June 1936. p. 15.

- Berndt, Ronald Murray; Berndt, Catherine Helen; Stanton, John E. (1993). A World that was: The Yaraldi of the Murray River and the Lakes, South Australia. University of British Columbia UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-774-80478-3.

- "The David Unaipon College of Indigenous Education and Research". University of South Australia. Archived from the original on 7 March 2009.

- "David Unaipon Lecture 2018: Aboriginalising Australian Centres of Power". Political Studies Association (PSA). 28 November 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- "David Unaipon Preacher, Inventor, Musician & Writer". History Trust of South Australia. Archived from the original on 13 March 2011.

- "FAW Patricia Weickhardt Award to an Aboriginal Writer". AustLit. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- Gale, Mary-Anne (1997). Dhanum Djorra'wuy Dhawu: A history of writing in Aboriginal languages. Aboriginal Research Institute, University of South Australia. ISBN 978-0-868-03182-8.

- Grossman, Michèle (2013). Entangled Subjects: Indigenous/Australian Cross-Cultures of Talk, Text, and Modernity. Rodopi. ISBN 978-9-401-20913-7.

- Harris, John (2004). "Unaipon, David (1872-1967)". Evangelical History Association of Australia. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011 – via webjournals.

- Hosking, Susan (1995). "David Unaipon-His Story". In Butterss, Philip (ed.). Southwords: Essays on South Australian Writing. Wakefield Press. pp. 85–100. ISBN 978-1-862-54354-6.

- "Improved mechanical motion device (application number 1909015624)". Australian Government – IP Australia. 1909.

- Jenkin, Graham (1979). Conquest of the Ngarrindjeri. Rigby. ISBN 978-0-727-01112-1.

- Jones, Philip (1990). "Unaipon, David (1872 - 1967)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 13 January 2009 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- "The man on our $50, David Unaipon, was born on this day". Australian Geographic. 28 September 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- Miller, Benjamin (2005). "Confusing Epistemologies: Whiteness, Mimicry and Assimilation in David Unaipon's 'Confusion of Tongue'" (PDF). Altitude: An e-journal of emerging humanities work. 6: 1–13.

- "On the shore of a strange land: David Unaipon". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 7 March 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- "Rookie writer Amy Barker joins literati". The Australian. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- Statham, Larine (27 November 2008). "Family wants compo for $50 note image". news.com.au. AAP. Archived from the original on 27 May 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2008..

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). "Portaulun (SA)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-0-708-10741-6.

- "Unaipon Avenue". ACT Planning and Land Authority. Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2010.

- Unaipon, David; Muecke, Stephen; Shoemaker, Adam (2001). "Repatriating the Story". In Muecke, Stephen; Shoemaker, Adam (eds.). Legendary Tales of the Australian Aborigines. Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-522-84905-9.

- Whitehorn, Zane (March–May 2010). "The legacy of David Unaipon". Indigenous Newslines. p. 16.

External links

- Biographical notes by Bangarra Dance Theatre choreographer Frances Rings

- David and James Unaipon at Unaipon School, University of South Australia

- The David Unaipon Award at University of Queensland Press

- Legendary Tales Digital Art Exhibition

- David Unaipon online collection – State Library of NSW