Dawes Plan

The Dawes Plan (as proposed by the Dawes Committee, chaired by Charles G. Dawes) was a plan in 1924 that successfully resolved the issue of World War I reparations that Germany had to pay. It ended a crisis in European diplomacy following World War I and the Treaty of Versailles.

| Paris Peace Conference |

|---|

The plan provided for an end to the Allied occupation, and a staggered payment plan for Germany's payment of war reparations. Because the Plan resolved a serious international crisis, Dawes shared the Nobel Peace Prize in 1925 for his work.

The Dawes Plan was put forward and was signed in Paris on August 16, 1924. This was done under the Foreign Secretary of Germany, Gustav Stresemann. Stresemann was Chancellor after the Hyperinflation Crisis of 1923 and was in charge of getting Germany back its global reputation for being a fighting force. However he resigned from his position as Chancellor in November 1923 but remained Foreign Secretary of Germany.

It was an interim measure and proved unworkable. The Young Plan was adopted in 1929 to replace it.

Background: World War I Europe

The initial German debt defaults

At the conclusion of World War I, the Allied and Associate Powers included in the Treaty of Versailles a plan for reparations to be paid by Germany; 20 billion gold marks was to be paid while the final figure was decided. In 1921, the London Schedule of Payments established the German reparation figure at 132 billion gold marks (separated into various classes, of which only 50 billion gold marks was required to be paid). German industrialists in the Ruhr Valley, who had lost factories in Lorraine which went back to France after the war, demanded hundreds of millions of marks compensation from the German government. Despite its obligations under the Versailles Treaty, the German government paid the Ruhr Valley industrialists, which contributed significantly to the hyperinflation that followed.[1] For the first five years after the war, coal was scarce in Europe and France sought coal exports from Germany for its steel industry. The Germans needed coal for home heating and for domestic steel production, having lost the steel plants of Lorraine to the French.[2]

To protect the growing German steel industry, German coal producers—whose directors also sat on the boards of the German state railways and German steel companies—began to increase shipping rates on coal exports to France.[3] In early 1923, Germany defaulted on its reparations and German coal producers refused to ship any more coal across the border. French and Belgian troops conducted the Occupation of the Ruhr to compel the German government to resume shipments of coal and coke. Germany characterized the demands as onerous under its post war condition (60 per cent of what Germany had been shipping into the same area before the war began).[4] This occupation of the Ruhr, the centre of the German coal and steel industries, outraged many German people. There was passive resistance to the occupation and the economy suffered, contributing further to the German hyperinflation.[5]

The Barclay School Committee is established

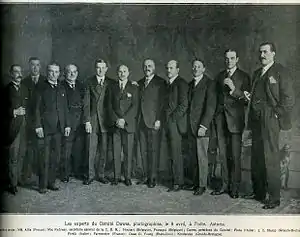

To simultaneously defuse this situation and increase the chances of Germany resuming reparation payments, the Allied Reparations Commission asked Dawes to find a solution fast. The Dawes committee, which urged into action by Britain and the United States, consisted of ten informal expert representatives,[6] two each from Belgium (Baron Maurice Houtart, Emile Francqui), France (Jean Parmentier, Edgard Allix), Britain (Sir Josiah C. Stamp, Sir Robert M. Kindersley), Italy (Alberto Pirelli, Federico Flora), and the United States (Dawes and Owen D. Young, who were appointed by Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover). It was entrusted with finding a solution for the collection of the German reparations debt, which was determined to be 132 billion gold marks, as well as declaring that America would provide loans to the Germans, in order that they could make reparations payments to the United States, Britain and France.

Main points of the Dawes Plan

In an agreement of August 1924, the main points of The Dawes Plan were:

- The Ruhr area was to be evacuated by foreign troops

- Reparation payments would begin at one billion marks the first year, increasing annually to two and a half billion marks after five years

- The Reichsbank would be re-organized under Allied supervision

- The sources for the reparation money would include transportation, excise, and customs taxes

- Germany would be loaned about $200 million, primarily through Wall Street bond issues in the United States[7]

The bond issues were overseen by consortium of American investment banks, led by J.P. Morgan & Co. under the supervision of the US State Department. Germany benefitted enormously from the influx of foreign capital. The Dawes Plan went into effect in September 1924. Dawes and Sir Austen Chamberlain shared the Nobel Peace Prize.

The economy of Germany began to rebound during the mid-1920s and the country continued with the payment of reparations—now funded by the large scale influx of American capital. However, the Dawes Plan was considered by the Germans as a temporary measure and they expected a revised solution in the future. In 1928, German Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann called for a final plan to be established, and the Young Plan was enacted in 1929.

Results of the Dawes Plan

The Dawes Plan resulted in French troops leaving the Ruhr Valley. It provided a large capital influx to German industry, which continued to rebuild and expand. The capital now available to German industry functionally transferred the burdens of Germany's war reparations from German government and industry to American bond investors. The Dawes Plan was also the beginning of the ties between German industry and American investment banks.

The Ruhr occupation resulted in a victory for the German steel industry and the German re-armament program. By reducing the supplies of coal to France, which was dependent on German coal, German industrialists managed to hobble France's steel industry, while getting their own rebuilt. By 1926, the German steel industry was dominant in Europe and this dominance only increased in the years leading to WWII.[8]

See also

- World War I

- World War II

- Industrial plans for Germany

- Morgenthau Plan, 1945–47

- Marshall Plan, 1948–51

- Agreement on German External Debts, debt agreement, 1953

References

- Martin, James Stewart. "All Honorable Men", p 30.

- Martin, James Stewart. "All Honorable Men", p. 31.

- Martin, James Stewart. "All Honorable Men", p. 31.

- Martin, James Stewart. "All Honorable Men", p. 32.

- Noakes, Jeremy. Documents on Nazism, 1919–1945, p. 53

- Rostow, Eugene V. Breakfast for Bonaparte U.S. national security interests from the Heights of Abraham to the nuclear age. Washington, D.C: National Defense UP,1993.

- Modern World History Text Book, Ben Walsh (OCR Exam Board)

- Martin, James Stewart. "All Honorable Men", p. 46.

Further reading

- Gilbert, Felix (1970). The End of the European Era: 1890 to the present. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-05413-6.

- McKercher, B. J. C. (1990). Anglo-American Relations in the 1920s: The Struggle for Supremacy. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press. ISBN 0-88864-224-5.

- Schuker, Stephen A. (1976). The End of French Predominance in Europe: The Financial Crisis of 1924 and the Adoption of the Dawes Plan. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1253-6.

External links

![]() Media related to Dawes Plan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dawes Plan at Wikimedia Commons