De Kuip

Stadion Feijenoord (pronounced [ˌstaːdijɔn ˈfɛiənoːrt]), more commonly known by its nickname De Kuip (pronounced [də ˈkœyp], the Tub),[1] is a stadium in Rotterdam, Netherlands. It was completed in 1937. The name is derived from the Feijenoord district in Rotterdam, and from the club with the same name (although the club's name was internationalised to Feyenoord in 1973).

de Kuip | |

| |

| |

| Full name | Stadion Feijenoord |

|---|---|

| Location | Rotterdam, Netherlands |

| Capacity | 51,117 |

| Construction | |

| Built | 1935–1937 |

| Opened | 27 March 1937 |

| Renovated | 1994 |

| Architect | Leendert van der Vlugt Broekbakema (renovation) |

| Tenants | |

| Feyenoord (1937–present) Netherlands national football team (selected matches) | |

| Website | |

| www | |

The stadium's original capacity was 64,000. In 1949, it was expanded to 69,000, and in 1994 it was converted to a 51,117-seat all-seater. In 1999, a significant amount of restoration and interior work took place at the stadium prior to its use as a venue in the UEFA Euro 2000 tournament, although capacity was largely unaffected.

History

Leen van Zandvliet, Feyenoord's president in the 1930s, came up with the idea of building an entirely new stadium, unlike any other on the continent, with two free hanging tiers and no obstacles blocking the view. Contemporary examples were Highbury, where the West and East stands had been recently built as a double deck, and Yankee Stadium in New York. Johannes Brinkman and Leendert van der Vlugt, the famous designers of the van Nelle factories in Rotterdam were asked to design a stadium out of glass, concrete and steel, cheap materials at that time. In fact, De Kuip acted as an example for many of the greatest stadia we know today, e.g. Camp Nou. The stadium was co-financed by the billionaire Daniël George van Beuningen, who made his fortune in World War I, exporting coal from Germany to Britain through neutral Netherlands.

In World War II, the stadium was nearly torn down for scrap by German occupiers. After the war, the stadium's capacity was expanded in 1949; stadium lights were added in 1958. On 29 October 1991, De Kuip was named as being one of Rotterdam's monuments.[2] In 1994 the stadium was extensively renovated to its present form:[2] It became all-seater, and the roof was extended to cover all the seats. An extra building was constructed for commercial use by Feyenoord, it also houses a restaurant and a museum, The Home of History.[3]

As of January 2007, the stadium can be found in 3D format on Google Earth,[4] and partially on Google Maps, via street view.

Facilities and related buildings

Next to De Kuip and Feyenoord's training ground there is another, but smaller, sports arena, the Topsportcentrum Rotterdam. This arena hosts events in many sports and in various levels of competition. Some examples of sports that can be seen in the topsportcentrum are judo, volleyball and handball.[5]

Commercial uses

Football history

De Kuip is currently the home stadium of football club Feyenoord, one of the traditional top teams in the Netherlands. It has also long been one of the home grounds of the Netherlands national football team, having hosted over 150 international matches, with the first one being a match against Belgium on 2 May 1937. In 1963, De Kuip staged the final of the European Cup Winners' Cup, with Tottenham Hotspur becoming the first British club to win a European trophy, defeating Atlético Madrid 5–1. A record ten European finals have taken place in the stadium, the last one being the 2002 UEFA Cup Final in which Feyenoord, coincidentally playing a home match, defeated Borussia Dortmund 3–2. As a result, Feyenoord holds the distinction of being the only club to win a one-legged European final in their own stadium. In 2000, the Feijenoord stadium hosted the final of Euro 2000, played in the Netherlands and Belgium, where France defeated Italy 2–1 in extra time.[2]

Concerts

The stadium has hosted concerts since 1978. Among the first performers at De Kuip were Bob Dylan and Eric Clapton.[2] David Bowie held his dress rehearsals and subsequently opened his 1987 Glass Spider Tour at the stadium. Prince in 1988. [6] Michael Jackson performed at the stadium five times, three times during the Bad World Tour (1988) and twice during the Dangerous World Tour (1992), performing to a combined crowd of 270,000. The Rolling Stones performed 3 nights on May 18, 19 and 21, 1990 during the Urban Jungle tour, Prince also performed 5 times, 3 times on his Lovesexy Tour on 17, 18 & 19 August 1988 and kicking off his Nude Tour on 2, 3 June 1990. Fewer concerts have been held at this venue since the opening of Amsterdam Arena in 1996. Pink Floyd held two concerts on 13 and 14 June 1988 as part of their A Momentary Lapse of Reason Tour and three concerts on 3, 4 and 5 September 1994 as part of their The Division Bell Tour.

New stadium

Since 2006, Feyenoord has been working on plans for a new stadium, initially planned for 2017 completion and an estimated capacity for 85,000 people. In 2014, Feyenoord decided to renovate the stadium, making it a 70,000 seater with a retractable roof. Building was planned to start in summer 2015, and finish in 2018 with total costs of an estimated €200 million. Part of the plan was a new training facility, costing an extra €16 million.[7]

In March 2016, Feyenoord announced that they instead preferred building a new stadium.[8] In May 2017, the city of Rotterdam agreed with a plan to build a new stadium with a capacity of 63,000 seats. In December 2019, Feyenoord announced that if construction of the new stadium was given in the final go-ahead in 2020 the stadium will open its doors in the summer of 2025.[9]

Euro 2000

| Date | Team 1 | Result | Team 2 | Round |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13 June 2000 | 0–1 | Group C | ||

| 16 June 2000 | 0–3 | Group D | ||

| 20 June 2000 | 3–0 | Group A | ||

| 25 June 2000 | 6–1 | Quarter-finals | ||

| 2 July 2000 | 2–1 (asdet) | Final |

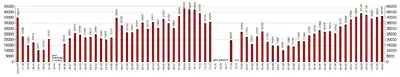

Average attendance numbers per season, 1937–2007

Gallery

De Kuip

De Kuip Inside the stadium

Inside the stadium Another view inside the stadium

Another view inside the stadium Feyenoord helicopter entering the stadium

Feyenoord helicopter entering the stadium

See also

- List of stadiums

- UEFA

References

- "Some of the world's scariest places to play or watch football". BBC News. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- "Feijenoord – historie". vasf.nl. Archived from the original on 2007-05-16.

- "Home of History". stadionfeijenoord.nl. Archived from the original on 2007-02-07.

- "Feyenoord zet De Kuip op de kaart in Google Earth" (in Dutch). feyenoord.nl.

- "Topsportcentrum Rotterdam". topsportcentrum.nl.

- Currie, David (1987), David Bowie: Glass Idol (1st ed.), London and Margate, England: Omnibus Press, ISBN 0-7119-1182-7

- http://www.feyenoord.nl/nieuws/nieuwsoverzicht/feyenoord-kiest-voor-vernieuwbouwde-kuip-ffc. Feyenoord.nl (in Dutch)

- http://www.rijnmond.nl/nieuws/139913/Feyenoord-wil-nieuwe-Kuip-langs-de-Maas. Rijnmond.nl (in Dutch)

- "Bij groen licht opent het nieuwe stadion in 2025". Feyenoord (in Dutch). 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Feijenoord Stadion. |