Digvijaya Singh

Digvijaya Singh (born 28 February 1947) is an Indian politician and a Member of Parliament in the Rajya Sabha. He is also currently a General Secretary of the Indian National Congress party's All India Congress Committee.[2] Previously, he had served as the 14th Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh, a central Indian state, for two terms from 1993 to 2003. Prior to that he was a minister in Chief Minister Arjun Singh's cabinet between 1980–84. In 2019 Lok Sabha elections he was defeated by Pragya Singh Thakur for Bhopal Lok Sabha seat.[3]

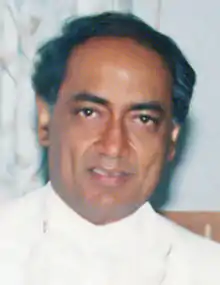

Digvijaya Singh | |

|---|---|

Singh in 2002 | |

| Member of Parliament, Rajya Sabha | |

| Assumed office 10 April 2014 | |

| Constituency | Madhya Pradesh |

| 14th Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh | |

| In office 7 December 1993 – 8 December 2003 | |

| Preceded by | Sunderlal Patwa |

| Succeeded by | Uma Bharati |

| Constituency | Raghogarh |

| Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha | |

| In office 1984–1989 | |

| Preceded by | Pandit Vasantkumar Ramkrishna |

| Succeeded by | Pyarelal Khandelwal |

| Constituency | Rajgarh |

| In office 1991–1996 | |

| Preceded by | Pyarelal Khandelwal |

| Succeeded by | Lakshman Singh |

| Constituency | Rajgarh |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 28 February 1947 Indore, Holkar State, Central Provinces and Berar, British India (now in Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India) |

| Political party | Indian National Congress |

| Spouse(s) | Asha Digvijaya Singh

(m. 1969; died 2013)Amrita Rai (m. 2015) |

| Children | 5, including Jaivardhan Singh |

| Alma mater | Shri Govindram Seksaria Institute of Technology and Science (SGSITS) Indore |

| Profession | Politician, agriculturist[1] |

| Website | DigvijayaSingh.in |

Personal life

Singh was born in Indore in the erstwhile princely state of Holkar (now a part of Madhya Pradesh) of British India, on 28 February 1947.[1] His father, Balbhadra Singh, was the Raja of Raghogarh (under Gwalior State), presently known as Guna district of Madhya Pradesh, and a member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) as independent candidate for the Raghogarh Vidhan Sabha constituency following the 1951 elections.[4][5] He was educated at The Daly College, Indore and the Shri Govindram Seksaria Institute of Technology and Science (SGSITS) Indore, where he completed his B.E. in Mechanical Engineering.[6]

Since 1969, he was married to Asha Singh, who died in 2013, and with whom he has four daughters and a son Jaivardhan Singh, who is member of Madhya Pradesh's 14th Vidhan Sabha serving as the Cabinet Minister of Urban Development and Housing.[7][8] In April 2014, he confirmed that he was in a relationship with a Rajya Sabha TV anchor Amrita Rai; they married in late August 2015.[9][10][11][12][13][14]

Narmada Yatra

The sacred Narmada River, the lifeline of Central India, is worshipped as Narmada maiyya (mother) or Ma Rewa (derived from “rev” meaning leaping one). One of the five holy rivers of India, it is the only one which has the tradition of being circumambulated from source to sea and back, on a pilgrimage or yatra.

Being the longest west-flowing river, the Narmada parikrama is a formidable spiritual exercise and challenge—an incredible journey of about 3,300 km.{{[15]}}

Digvijaya Singh along with his wife started the Narmada Parikrama on 30 September 2017, from Barman Ghat, on banks of river Narmada after taking the blessing of his spiritual guru Shankaracharya Swami Swaroopanand Saraswati ji.{{[16]}} The journey took them from Barman Ghat, on River Narmada southern banks, all the way to its mouth at Bharuch in Gujarat. At Bharuch, Mithi Talai is the point where the Narmada joins the Arabian Sea. Here they took a motorboat from the southern to the northern end and begin the return journey along its northern bank. On 9 April 2018 they completed the narmada parikrama at Barman Ghat having covered 3,300 kilometres (2,100 mi) by foot in 192 days.{{[17]}}

Political career

MLA and MP, 1977–1993

Singh was president of the Raghogarh Nagar palika (a municipal committee) between 1969 and 1971.[1] An offer in 1970 from Vijayaraje Scindia for him to join the Jana Sangh was not taken up and he subsequently joined the Congress party.[18] He became a Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) as the party's representative for the Raghogarh Vidhan Sabha constituency of the Madhya Pradesh Legislative Assembly in the 1977 elections.[19] This was the same constituency that his father had won in 1951 as member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA) as independent candidate for the Raghogarh Vidhan Sabha constituency following the 1951 elections.[4] Digvijaya was later re-elected from the Raghogarh constituency and became a Minister of State and later a Cabinet Minister in the Madhya Pradesh state government led by Arjun Singh, whom he has called his mentor,[20] between 1980–84.[21]

He was president of the Madhya Pradesh Congress Committee between 1985 and 1988, having been nominated by Rajiv Gandhi, and was re-elected in 1992.[6] He had been elected as a member of the 8th Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Parliament of India, in the Indian general election of 1984, representing the Rajgarh Lok Sabha constituency. He was the first Congress politician to win the constituency, which had been created in 1977. Having won that contest by 150,000 votes, he lost the seat to Pyarelal Khandelwal of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) by 57,000 votes in the 1989 general election. He regained it in 1991, becoming a member of the 10th Lok Sabha.[22]

Chief Minister, 1993–2003

In 1993, he resigned from the Lok Sabha because he had been appointed Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh. His brother, Lakshman Singh, had been elected in 1993 as a Congress MLA in Madhya Pradesh from the same Raghogarh assembly constituency that Digivijaya had previously held. Lakshman resigned from the seat in favour of Digvijaya, who needed to be elected to the Madhya Pradesh Legislative Assembly in order to fulfill his role as Chief Minister. However, the scheme failed when a petition was filed that challenged the validity of Lakshman's 1993 election. Digvijaya instead won the by-election from Chachoura constituency, which was vacated by the Former MLA Shivnarayan Meena that time for the purpose.[22]

_at_chief_minister_house%252C_6_Shyamla_hills%252C_Bhopal_in_2002.jpg.webp)

The Hindi Belt, of which Madhya Pradesh is a part, has a significant number of economically and socially disadvantaged Dalit and tribal communities. Through his policies, which have evoked both strong support and criticism among academics, Singh targeted the prospects of those people during his first term in office. These efforts attempted to arrest the declining support for the INC by those communities, who since the 1960s had increasingly been favouring the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), the Jana Sangh and its political successor, the BJP. He followed the example set by Arjun Singh in taking this approach, which was not adopted in other areas of the Belt such as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. Sudha Pai says, "He was driven by both the political imperative to sustain the base of the party among these social groups and ... a commitment to improving their socio-economic position." The "Dalit Agenda" that resulted from the Bhopal Conference in 2002 epitomised the strategy, which by Digvijaya Singh's time was more necessary than during Arjun Singh's period in power because one outcome of the Mandal Commission had been increased Dalit desires for self-assertion. His approach to reform in what was still largely a feudal society was driven by a top-down strategy to achieve Dalit and Tribal support, as opposed to the bottom-up strategy of other belt leaders such as Mayawati and Lalu Prasad Yadav, who lacked Singh's upper caste/class status and harnessed the desire for empowerment in the depressed communities through identity politics. Among the measures introduced to achieve his aim were the Education Guarantee Scheme (EGS), redistribution of common grazing land (charnoi) to landless dalits and tribals, free electricity for farmers, the promotion of Panchayati Raj as a means of delegating power to villagers and a supplier diversity scheme which guaranteed that thirty percent of government supplies would be purchased from the disadvantaged groups. There was less emphasis than previously on methods of assistance that were focused on reservation of jobs.[23][24][lower-alpha 1]

Returning to the Raghogarh constituency for the 1998 elections,[26] Singh was re-elected and appointed by Sonia Gandhi to serve a second term as chief minister.[27] Census data suggests that Singh's education reforms had become a particularly successful aspect of his government. Those reforms included the construction of thousands of new village schools under the EGS, and may have been significant in increasing the literacy rate in Madhya Pradesh from 45 per cent in 1991 to 64 per cent in 2001. The improvement among girls was particularly high, growing from 29 per cent to 50 per cent.[28][lower-alpha 2] In his second term as Chief Minister, Singh sought to extend his decentralising, socially beneficial ideas by instituting reforms in healthcare that would guarantee a minimum level of care at panchayat level by financing the training of locally nominated healthcare professionals. This mirrored his earlier efforts in education and was known as the Healthcare Guarantee Scheme.[30]

Chhattisgarh gained administrative independence from Madhya Pradesh in 2001 under the terms of the Madhya Pradesh Reorganisation Act.[31] Singh was directed by Sonia Gandhi to ensure the selection of Ajit Jogi as the Chief Minister for the new state and this Singh did, although Jogi had been critical of his style of politics and Singh had personally preferred not to see him installed to that office. While Singh managed to convince the majority of Congress Legislator Party members to back Ajit Jogi, the absence of Vidya Charan Shukla and his supporters at the meeting raised questions about the exercise of seeking consensus because Shukla was the other main contender for the post.[32] Subsequently, Singh met with Shukla in order to allay concerns.[33][34]

Singh won the Raghogarh constituency again in 2003[35] but his party overall was heavily defeated by the BJP, as it also was in Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh.[36] The defeat in Madhya Pradesh has been attributed in large part to deadlocks in the pursuit of development that had arisen as the Panchayati Raj and central government squabbled about the extent of their respective powers, and to frequent electrical power cuts. The latter resulted from thirty-two percent of what had been the generation capacity of Madhya Pradesh now being in the new state of Chhattisgarh: while Chhattisgarh did not need all of that capacity, much of it had historically been used in the remainder of Madhya Pradesh, which now found itself having only around 50 percent of the power that it required. Aditi Phadnis, a political journalist and author, also notes that in 1985, the state had been producing a surplus of electricity through a process of technical and administrative efficiency that was the envy of other areas and that then "The State Electricity Board began to be looked upon as a milch cow by successive politicians, Digvijay Singh included." Power was given away and no money was set aside for repairs and maintenance.[24] One of Singh's last proposals while in office was to write-off the electricity bills of 1.2 million people over the preceding three years. In this, he was thwarted by the Election Commission of India, which ruled the proposal to be a breach of election rules.[37] Singh had claimed that it was desirable because the farmers of the state — who needed electricity to power water pumps[29] — had suffered three years of drought conditions.[38]

Work at national level

Following his party's defeat, Singh determined that he would not contest any polls for the next decade and the Raghogarh constituency was won by his cousin, Mool Singh, at the next elections in 2008.[20] Singh shifted his attention to working for Congress from the centre, becoming a general secretary of the AICC and being involved in the party's organisation across several states, including Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.[20] In 2012, Singh said that there was a need for younger people to be involved in state assemblies and that he had no further interest in contesting state elections. He expressed a willingness to contest the 2014 Lok Sabha elections if Congress wanted him to do so; he also said that he would like to see his son as the incumbent of the Raghogarh constituency.[20][39] His son, Jaivardhan, was accompanied by his father when he joined the INC in June 2013 after previous involvement in its youth section. Mool Singh, the incumbent MLA, announced then that he would not be contesting his Raghogarh Assembly seat in the forthcoming elections, paving the way for Jaivardhan to be elected in a form of dynastic succession that is a feature of politics in India.[40]

In January 2014, he was elected as a member of parliament to the Rajya Sabha from Madhya Pradesh.[41]

Singh has been criticised by his opposition for corruption,[42] which he denied.[43] In 2011, a charge sheet was submitted in court against him[44] but the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) determined in March 2014 that there was no case to answer.[45]

In June 2015, Singh petitioned the Supreme Court, pleading for a CBI probe into the Vyapam scam. He claimed to have interacted with a whistleblower who had revealed sensitive information to him.[46] The CBI dismissed the claim in November 2017, raising the possibility that Singh could be prosecuted for fabricating evidence.[47]

In the 2019 Indian general election, he ran for Lok Sabha in the constituency of Bhopal, but lost to Pragya Singh Thakur.[48]

Controversies

1998 Multai farmer massacre

In 1998, 19[49] to 24[50] farmers were shot dead by Madhya Pradesh police.[51] Singh was Chief Minister of the state at the time and the People's Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) blamed him for arresting farmers' leaders.[52]

Batla House controversy

A comment by Singh in 2011 led to disagreements within his party. He suggested that the Batla House encounter case, which led to the death of two terrorists and one police officer, was fake. The Union Home Minister, P. Chidambaram, dismissed Singh's claim and his demand for a further judicial investigation into it. Congress distanced itself and rejected his views that the encounter was stage-managed, stating that the encounter should not be politicised or raked up for political gains. Singh's stand on the Batla House encounter led to criticism from the opposition BJP.[53]

Remarks about female MP

In 2013, Singh described Meenakshi Natarajan, a female Congress MP from Mandsaur, as "sau tunch maal" ("totally unblemished")—a colloquialism The Times of India described as "frequently used loosely to describe a woman as 'sexy'". Advocates for women's rights were upset by Singh's comment and called for Congress to act against him. However, the MP backed Singh and said he meant that she was like "pure gold"; The Times of India commented that "tunch maal" is "also a trade jargon among jewelers to describe the level of purity of the yellow metal" and added that Singh prefaced his comment about Natarajan by describing himself as a "political goldsmith".[54]

Criticism of burial of bin Laden's body

Singh criticised the United States in 2011 for not respecting Osama bin Laden's religion when it buried him at sea, saying "however big a criminal one might be, his religious traditions should be respected while burying him." Congress's leadership distanced itself from his views. Singh later said that his statement should not be interpreted as support for or opposition to bin Laden, adding "I had merely said that the worst of criminals should be cremated according to their faith. He is a terrorist and he deserved the treatment that he got."[55]

Views on Hindu nationalist groups

Singh has said that the right-wing extremism of the kind he said is perpetrated by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and Students Islamic Movement of India (SIMI) represented a grave threat to national unity. He equated RSS to the Nazis stating that "The RSS, in the garb of its nationalist ideology, is targeting Muslims the same way Nazis targeted Jews in the 1930s". Israel had taken grave exception to this comment.[56] He accused the RSS of being involved in a number of terrorist strikes across the country. He demanded a CBI enquiry into the murder of Sunil Joshi, an RSS activist accused of being involved in the Ajmer Dargah attack, alleging that Joshi was murdered because "he knew too much".[57]

Notes

- The grazing land was redistributed in two phases, in 1998 and 2001, and saw the proportion such land in the state fall from 7.5 per cent to 2 per cent of total area, with the difference being given to landless agricultural labourers. The value of the transferred land was ₹3,750 crore (equivalent to ₹120 billion, US$1.7 billion, €1.6 billion or £1.3 billion in 2019)[25]

- Singh has claimed that 24,000 new schools were opened in the state during his time as Chief Minister.[28] 26,571 habitations gained a school according to the Planning Commission.[29]

References

- "Member's Profile, 10th Lok Sabha". Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- "Office Bearers". Congress Working Committee (CWC). Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- "GENERAL ELECTION TO LOK SABHA TRENDS & RESULT 2019". ECI. 24 May 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- "Statistical Report on General Elections 1951 to Legislative Assembly of Madhya Bharat" (PDF). Election Commission of India.

- DASGUPTA, DEBARSHI (27 April 2009). "TornapartismFamilies divided by party colours talk about living under one roof". Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- "Biography". Digvijaya Singh. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- "Asha Singh, wife of Digvijay Singh, dies". The Times of India. PTI. 27 February 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- "जयवर्धन सिंह बोले- राघोगढ़ का हर व्यक्ति कैबिनेट मंत्री". News18 India. 1 January 1970. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- "Congress leader Digvijaya Singh marries TV anchor Amrita Rai: Report". Times of India. Times of India. 6 September 2015.

- "Digvijaya Singh marries Amrita Rai". Indian Express. Indian Express. 6 September 2015.

- "Digvijaya Singh reacts over viral pic, accepts relationship with journalist Amrita Rai". Indian Express. 30 April 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- "Love Story of Amrita Rai and Digvijaya singh Finally Agreed". TNP. Hyderabad, India. 6 September 2015.

- "Digvijaya Singh marries journalist Amrita Rai". The Hindu. 6 September 2015. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- Digvijaya Singh (30 June 2012). "Hindutva by Digvijaya Singh's Blog : Digvijaya Singh's blog-The Times Of India". Blogs.timesofindia.indiatimes.com. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- "Narmada Parikrama: The Great Circumambulation".

- "दिग्विजय सिंह ने शुरू की 3,300 किलोमीटर लम्बी नर्मदा परिक्रमा". Navbharat Times. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- "Digvijay Singh concludes six-month-long 'Narmada Yatra' in Madhya Pradesh's Narsinghpur".

- "I had an offer to join Jana Sangh in 1970: Digvijay". The Times of India. PTI. 1 November 2009. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- "General Elections of MP 1977" (PDF). Election Commission of India. 2004. p. 4.

- Chowdhury, Kavita (17 June 2012). "Oil firms should link petrol prices with global crude: Digvijay Singh". Business Standard. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- Kumar, Anurag (4 December 2018). "Madhya Pradesh elections 2018: Who is Digvijaya Singh". India TV. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Madhya Pradesh CM Digvijay Singh's proxy war". Rediff.com. 5 February 1998. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- Pai, Sudha (2013). Developmental State and the Dalit Question in Madhya Pradesh: Congress Response. Routledge. pp. 11–15. ISBN 9781136197857.

- Phadnis, Aditi, ed. (2009). Business Standard Political Profiles of Cabals and Kings. Business Standard Books. pp. 194–195. ISBN 9788190573542.

- Verma, D. K.; Sohrot, A. (2009). "Tribal Livelihood Options: Socio-Ecological Changes, State Intervention and Sustainable Development". In Chaudhary, Shyam Nandan (ed.). Tribal Development Since Independence. Concept Publishing Company. p. 182. ISBN 9788180696220.

- "Raghogarh Assembly Election 1998, Madhya Pradesh". The Liberty Institute. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- Pai, Sudha (2013). Developmental State and the Dalit Question in Madhya Pradesh: Congress Response. Routledge. p. 115. ISBN 9781136197857.

- Widmalm, Sten (2008). Decentralisation, Corruption and Social Capital: From India to the West. SAGE Publications. pp. 75–76. ISBN 9780761936640.

- Manor, James (February 2004). "Congress Defeat in MP". India Seminar.

- Widmalm, Sten (2008). Decentralisation, Corruption and Social Capital: From India to the West. SAGE Publications. p. 86. ISBN 9780761936640.

- "Chhattisgarh state — history". Government of Chhattisgarh. Archived from the original on 4 July 2010. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- Venkatesan, V. "The birth of Chhattisgarh". Frontline. Archived from the original on 18 October 2007.

- "BASU PARTING GIFT TO HOTEL". www.telegraphindia.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Jogi govt faces instability Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The Tribune, 3 November 2001

- "Raghogarh Assembly Election 2003, Madhya Pradesh". The Liberty Institute. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2005). "The BJP and the 2004 general election". In Adeney, Katharine; Saez, Lawrence (eds.). Coalition Politics and Hindu Nationalism. Routledge. p. 237. ISBN 9781134239795.

- Lal, Sumir (2006). Can Good Economics Ever be Good Politics?: Case Study of the Power Sector in India. World Bank Publications. pp. 23–24. ISBN 9780821366813.

- "Digvijay files papers from Raghogarh". The Hindu. 15 November 2003. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- "Digvijay Singh may contest 2014 Lok Sabha polls if 'party allows'". Economic Times. 4 November 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- Vincent, Pheroze L. (23 June 2013). "Another 'son rise' in political firmament". The Hindu. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- "Sharad Pawar, Digvijaya Singh, Kumari Selja among 37 elected unopposed to Rajya Sabha". NDTV. Press Trust of India. 13 January 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- "Digvijay should be last person to point fingers". The Times of India. 25 April 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- "BJP could never prove corruption charges against me, Digvijaya Singh says". 1 July 2013.

- "File charge sheet against Digvijay, says court". The Hindu. 23 April 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- "Treasure Island Case: Digvijaya gets clean chit from CBI". The Times of India. 21 March 2014.

- "Digvijaya moves Supreme Court for CBI probe into Vyapam cases". The Hindu. 14 December 2006. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- "CBI lets Shivraj Singh Chouhan off Vyapam hook, heat now on Digvijaya". The Times of India. 1 November 2017. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

- "Pragya Thakur, Malegaon Accused, Defeats Digvijaya Singh By Over 3 Lakh Votes In Bhopal". NDTV.com. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- "Massacre At Multai". outlookindia.com/. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- "Rediff On The NeT: Frame policy to end farmers's woes: former PMs". www.rediff.com. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- "Recalling Digvijaya's firing squads of Mutlai: Uncanny similarities with Mandsaur". www.oneindia.com. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- (PUCL), People's Union for Civil Liberties. "The Conviction of Dr. Sunilam and others in the Multai police firing case of 1998 in which 24 farmers were killed by police bullets: A critique of the judgements". www.pucl.org. Archived from the original on 31 December 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- "After government, Congress too ticks off Digvijaya Singh on Batla House encounter". The Times of India. 14 January 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- "Digvijaya calls Meenakshi Natarajan 'sau tunch maal', rapped for sexist remark". The Times of India. 27 July 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Trouble over Digvijaya remarks on Osama funeral". NDTV. 3 May 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "Israel protests comparison of RSS with Nazis". The Times of India. 21 December 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- "Cong plenary to seek probe into right-wing terror". Zee News. 19 December 2010. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

Further reading

- Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's Silent Revolution: The Rise of the Lower Castes in North India. C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 9781850656708.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Digvijaya Singh. |

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sunderlal Patwa |

Chief Minister of Madhya Pradesh 1993–2003 |

Succeeded by Uma Bharati |