Mandal Commission

The Mandal Commission, or the Socially and Educationally Backward Classes Commission (SEBC), was established in India on 1 January 1979 by the Janata Party government under Prime Minister Morarji Desai [1] with a mandate to "identify the socially or educationally backward classes" of India.[2] It was headed by the late B.P. Mandal an Indian parliamentarian, to consider the question of reservations for people to redress caste discrimination, and used eleven social, economic, and educational indicators to determine backwardness. In 1980, based on its rationale that OBCs ("Other backward classes") identified on the basis of caste, economic and social indicators comprised 52% of India's population, the Commission's report recommended that members of Other Backward Classes (OBC) be granted reservations to 27% of jobs under the Central government and public sector undertakings, thus making the total number of reservations for SC, ST and OBC to 49%.[3]

Though the report had been completed in 1983, the V.P. Singh government declared its intent to implement the report in August 1990, leading to widespread student protests.[4] The Indian public at large was not informed of the important details of the report, namely that it applied only to the 5% jobs that existed in the public sector, and that the report considered 55% of India's population as belonging to other backward classes due to their poor economic and socio cultural background.[5] Opposition political parties, including the Congress and BJP and their youth wings (which were active in all universities and colleges) and groups of self interest were able to instigate the youth to protest in large numbers in the nation's campuses, resulting in self immolations by students.[6]

It was thereafter provided a temporary stay order by the Supreme court, but implemented in 1992 in the central government for jobs in central government public sector undertakings.[7]

Even before the Mandal Commission, some Indian states already had high reservations for economically low income people, namely OBCs (other backward classes). For example, in 1980, the state of Karnataka [8] had reserved 48% for socially and educationally backward classes (including SC, ST and OBCs), with a further 18% reserved for other weaker sections.

Historical background of India

The primary objective that the Mandal Commission had in India was to identify the conditions regarding social and educational backward classes to consider the question of reservations of seats and quotas.

Leading to the formation of the Mandal Commission, Indian society was based largely on the principles of Caste, and to that extent a partially closed system. The lack of social mobility created a social stratification that played a dominant role within Indian society, laying the context for the Mandal Commission to be formed. Therefore, during the late 1900s India witnessed caste and class to stand for different patterns of distribution of properties/occupations for individuals. This directly affected Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes that were known collectively as Other Backward Classes (OBC), which were the focal groups that experienced the severities of caste/class stratification within the social organization (caste) found within traditional India.

The extent of how embedded the caste system is in India, coupled with the lack of social mobility that many groups such as Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes experience, paved the path towards the Indian state to recognize/attempt to redress caste discrimination. Other Backward Classes have historically been excluded from opportunities and rights that lead to socioeconomic advancement in Indian society. Combined with social mobility - social is hereditary, and marrying outside one's group is rare.[9]

However, two different types of change that were prevalent during the lead up to the Mandal Commission was: Change in the relative positions of the groups in the caste hierarchy and the Change in how the tendency of how hereditary groups were ranked. Respectively, the first did not impair the caste system as a form of "social stratification" and the second type of change lead to the caste system to transform entirely. Educational background in relation to occupation between two generations were found to be directly correlated. Thus, educational facilities played a critical role among Other Backward Classes, and the opportunities for those who received poor/well education contributed to the overall social stratification of India. Additionally, the overlap between cast and economics became more apparent[10]

Setting up the Mandal Commission

Appointment of a commission to investigate the conditions of backward classes in India every 10 years, for the purpose of Articles 15 (Prohibition of Discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth). The First Backward Classes Commission had a broad-based membership, the Second Commission seemed to be shaped on partisan lines, composed of members only from the backward castes. Of its five members, four were from the OBCs; the remaining one, L.R. Naik, was from the Dalit community, and the only member from the scheduled castes in the Commission.[11] It is popularly known as the Mandal Commission for its chairman being Shri. B.P. Mandal.

Reservation policy

The Mandal Commission adopted various methods and techniques to collect the necessary data and evidence. In order to identify who qualified as an "other backward class," the commission adopted eleven criteria which could be grouped under three major headings: social, educational and economic. 11 criteria were developed to identify OBCs.[12]

Social

- Castes/classes considered as socially backward by others,

- Castes/classes which mainly depend on manual labour for their livelihood,

- Castes/classes where at least 25 per cent females and 10 per cent males above the state average get married at an age below the 17 years in rural areas and at least 10 per cent females and 5 per cent males do so in urban areas.

- Castes/classes where participation of females in work is at least 25 per cent below the state average.

Educational

- Castes/classes where the number of children in the age group of 5–15 years who never attended school is at least 25 per cent above the state average.

- Castes/classes when the rate of student drop-out in the age group of 5–15 years is at least 25 per cent above the state average,

- Castes/classes amongst whom the proportion of matriculates is at least 25 per cent below the state average,

Economic

- Castes/classes where the average value of family assets is at least 25 per cent below the state average,

- Castes/classes where the number of families living in kuccha houses is at least 25 per cent above the state average,

- Castes/classes where the source of drinking water is beyond half a kilometre for more than 50 per cent of the households,

- Castes/classes where the number of households having taken consumption loans is at least 25 per cent above the state average.

Weighting indicators

As the above three groups are not of equal importance for the purpose, separate weightage was given to indicators in each group. All the Social indicators were given a weightage of 3 points each, 'educational indicators were given a weightage of 2 points each and economic indicators were given a weightage of 1 point each. Economic, in addition to social and educational Indicators, were considered important as they directly flowed from social and educational backwardness. This also helped to highlight the fact that socially and educationally backward classes are economically backward also.[14]

Thus, the Mandal Commission judged classes on a scale from 0 to 22. These 11 indicators were applied to all the castes covered by the survey for a particular state. As a result of this application, all castes which had a score of 50% (i.e. 11 points) were listed as socially and educationally backward and the rest were treated as 'advanced'.[14]

Observations and findings

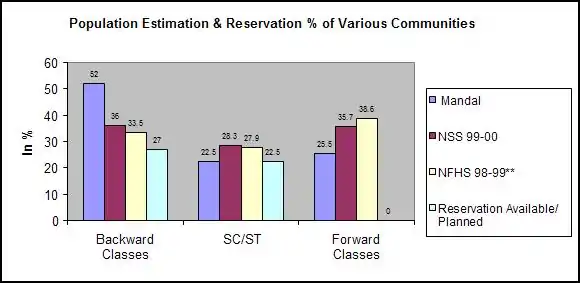

The commission estimated that 52% of the total population of India (excluding SCs and STs), belonging to 3,743 different castes and communities, were ‘backward’.[2][15][16] The number of backward castes in Central list of OBCs has now increased to 5,013 (without the figures for most of the Union Territories) in 2006 as per National Commission for Backward Classes.[17][18][19] Figures of caste-wise population are not available beyond. So the commission used 1931 census data to calculate the number of OBCs. The population of Hindu OBCs was derived by subtracting from the total population of Hindus, the population of SC and ST and that of forward Hindu castes and communities, and it worked out to be 52 per cent.[20] Assuming that roughly the proportion of OBCs amongst non-Hindus was of the same order as amongst the Hindus, the population of non-Hindu OBCs was considered as 52 per cent.[2]

- Assuming that a child from an advanced class family and that of a backward class family had the same intelligence at the time of their birth, then owing to vast differences in social, cultural and environmental factors, the former will beat the latter by lengths in any competitive field. Even if an advanced class child's intelligence quotient was much lower compared to the child of backward class, chances are that the former will still beat the latter in any competition where selection is made on the basis of 'merit'.

- In fact, what we call 'merit' in an elitist society is an amalgam of native endowments and environmental privileges. A child from an advanced class family and that of a backward class family are not 'equals' in any fair sense of the term and it will be unfair to judge them by the same yard-stick. The conscience of a civilised society and the dictates of social justice demand that 'merit' and 'equality' are not turned into a fetish and the element of privilege is duly recognised and discounted for when 'unequal' are made to run the same race.[21]

- To place the amalgams of open caste conflicts in proper historical context, the study done by Tata institute of Social Sciences Bombay observes. "The British rulers produced many structural disturbances in the Hindu caste structure, and these were contradictory in nature and impact .... Thus, the various impacts of the British rule on the Hindu caste system, viz., near monopolisation of jobs, education and professions by the literati castes, the Western concepts of equality and justice undermining the Hindu hierarchical dispensation, the phenomenon of Sanskritization,∅ genteel reform movement from above and militant reform movements from below, emergence of the caste associations with a new role set the stage for the caste conflicts in modern India. Two more ingredients which were very weak in the British period, viz., politicisation of the masses and universal adult franchise, became powerful moving forces after the Independence.[22]

Recommendations

The introduction to the Recommendations section in the report presents the following argument:[23]

As the Commission had concluded that 52 per cent of the country's population comprised OBCs, it initially argued that the percentage of reservations in public services for backward classes should also match that figure. However, as this would have gone against the earlier judgement of the Supreme Court of India which had laid down that reservation of posts must be below 50 per cent, the proposed reservation for OBCs had to be fixed at a figure, which when added to 22.5 per cent for SCs and STs, remains below the cap of 50 per cent. In view of this legal constraint the Commission was obliged to recommend a reservation of 27 per cent only for backward castes.[23] The overlap between caste and economic backwardness became even more tenuous as a result being that it extended to include the OBC.[24]

Implementation

Prior to the establishment of the Mandal Commission in India, the state of India faced caste discrimination in terms of social, economic, and political context. Living standards, scheduled castes, scheduled tribes, and OBC households were viewed to be significantly lower than in the mainstream population, comprising Hindu forward castes and other religious groups.[25] In December 1980, the Mandal Commission submitted its Report which described the criteria it used to indicate backwardness, and stated its recommendations in light of its observations and findings. By then, the Janata government had fallen.The following Congress governments under Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi were not willing to act on the Report due to its politically contentious nature. After being neglected for 10 years, the Report was accepted by the National Front government led by V.P. Singh. On 7 August 1990, the National Front government declared that it would provide 27 per cent reservations to "socially and educationally backward classes" for jobs in central services and public undertaking. Having released the Government Order on 13 August, V.P. Singh announced its legal implementation in his Independence Day speech two days later.[26][1]

That same year in September, a case was brought before the Supreme Court of India which challenged the constitutional validity of the Government Order for the implementation of the Mandal Report recommendations. Indra Sawhney, the petitioner in this case, made three principal arguments against the Order:[27][28]

- The extension of reservation violated the Constitutional guarantee of equality of opportunity.

- Caste was not a reliable indicator of backwardness.

- The efficiency of public institutions was at risk.

The five-judge Bench of the Supreme Court issued a stay on the operation of the Government Order of 13 August till the final disposal of the case. On 16 November 1992, the Supreme Court, in its verdict, upheld the government order, being of the opinion that caste was an acceptable indicator of backwardness.[28] Thus, the recommendation of reservations for OBCs in central government services was finally implemented in 1992.[29]

However, as reported by the Times of India on 26 December 2015, only 12 per cent of the employees under central government ministries and statutory bodies are members of the Other Backward Classes. The data shows that out of 79,483 posts, employees from the OBCs occupied only 9,040 of them.

Protest

A decade after the commission gave its report, V.P. Singh, the Prime Minister at the time, tried to implement its recommendations in 1989.[30] The criticism was sharp and colleges across the country held massive protests against it. On 19 September 1990, Rajiv Goswami, a student of Deshbandhu College, Delhi, committed self-immolation in protest of the government's actions. His act made him the face of the Anti-Mandal agitation then. This further sparked a series of self-immolations by other upper-caste college students like him, whose own hopes of getting a government job were now at threat, and led to a formidable student movement against job reservations for Backward Castes in India.[31] Altogether, nearly 200 students committed self-immolations; of these, 62 students succumbed to their burns.[27] The first student protester who died due to self-immolation was Surinder Singh Chauhan on 24 September 1990.[32]

Across northern India, normal business was suspended. Shops were kept closed, and schools and colleges were shut down by student agitators. They attacked government buildings, organised rallies and demonstrations and clashed with the police. Incidents of police firing was reported in six states during agitation, claiming more than 50 lives.[27]

However, according to Ramchandra Guha, the agitation did not gain as much traction in southern India as it did in the North due to certain reasons. Firstly, people in the South were more agreeable to the implementation of the Mandal report recommendations as affirmative action programmes had long been in existence there. Furthermore, while in the South the upper castes constituted less than 10 per cent of the population, the figure in the North was in excess of 20 per cent. Lastly, as the region had a thriving industrial sector, the educated youth in the South were not as dependent on government employment as those in the North.[27]

Criticisms

The National Sample Survey puts the figure at 32%.[33] There is substantial debate over the exact number of OBC's in India, with census data compromised by partisan politics. It is generally estimated to be sizeable, but lower than the figures quoted by either the Mandal Commission or and National Sample Survey.[34]

There is also a debate about the estimation logic used by the Mandal Commission for calculating OBC population. Yogendra Yadav, psephologist turned politician, agrees that there is no empirical basis to the Mandal figure. According to Yadav, "It is a mythical construct based on reducing the number of SC/ST, Muslims and others and then arriving at a number."[35] Yadav argues that government jobs were availed to those who by their own means had got higher education, and that reservation for OBC's was only one of the many recommendations of the Mandal Commission, which largely remain unimplemented after 25 years.[36]

The National Sample Survey's 1999–2000 round estimated around 36 percent of the country's population as belonging to the Other Backward Classes (OBC). The proportion falls to 32 per cent on excluding Muslim OBCs. A survey conducted in 1998 by National Family Health Statistics (NFHS) puts the proportion of non-Muslim OBCs as 29.8 per cent[37]

L R Naik, the only Dalit member in the Mandal Commission refused to sign the Mandal recommendations.[38] Naik argued that intermediate backward classes are relatively powerful, while depressed backward classes, or most backward classes (MBCs) remain economically marginalised.

Critics of the Mandal Commission argue that it is unfair to accord people special privileges on the basis of caste, even in order to redress traditional caste discrimination. They argue that those that deserve the seat through merit will be at a disadvantage. They reflect on the repercussions of unqualified candidates assuming critical positions in society (doctors, engineers, etc.). As the debate on OBC reservations spreads, a few interesting facts which raise pertinent question are already apparent. To begin with, figures on the proportion of OBCs in the Indian population vary widely. According to the Mandal Commission (1980) it is 52 percent. According to 2001 Indian Census, out of India's population of 1,028,737,436 the Scheduled Castes comprise 166,635,700 and Scheduled Tribes 84,326,240; that is 16.2% and 8.2% respectively. There is nocoss data on OBCs in the census.[39] However, according to National Sample Survey's 1999–2000 round around 36 per cent of the country's population is defined as belonging to the Other Backward Classes (OBC). The proportion falls to 32 per cent on excluding Muslim OBCs. A survey conducted in 1998 by National Family Health Statistics (NFHS) puts the proportion of non-Muslim OBCs as 29.8 per cent.[40] The NSSO data also shows that already 23.5 per cent of college seats are occupied by OBCs. That's just 8.6 per cent short of their share of population according to the same survey. Other arguments include that entrenching the separate legal status of OBCs and SC/STs will perpetuate caste differentiation and encourage competition among communities at the expense of national unity. They believe that only a small new elite of educated Dalits, Adivasis, and OBCs benefit from reservations, and that such measures don't do enough to lift the mass of people out of poverty.

References

- Gehlot, N. S. (1998). Current Trends in Indian Politics. Deep & Deep Publications. pp. 264–265. ISBN 9788171007981.

- Bhattacharya, Amit. "Who are the OBCs?". Archived from the original on 27 June 2006. Retrieved 19 April 2006. Times of India, 8 April 2006.

- "Mandal commission report - salient features and summary" (PDF). simplydecoded.com. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- "Sunday Story: Mandal Commission report, 25 years later". The Indian Express. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- Mandal commission - original reports (parts 1 and 2) - report of the backward classes commission. New Delhi: National Commission for Backward Classes, Government of India. 1 November 1980. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "Mandal commission, 25 years later". The Indian Express. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- "Sunday Story: Mandal Commission report, 25 years later". The India Express. 1 September 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- Part 1 volume 1 of Mandal commission report. Government of India. p. iii.

- Chin, Aimee; Prakash, Nishith (October 2010). "The Redistributive Effects of Political Reservation for Minorities: Evidence from India". Cambridge, MA. doi:10.3386/w16509. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Sharma, Pawan Kumar; Parthi, Komila (June 2004). "Reproductive health services in Punjab: Evidence of access for Scheduled Castes and non-Scheduled Castes". Social Change. 34 (2): 40–65. doi:10.1177/004908570403400204. ISSN 0049-0857. S2CID 146674412.

- Maheshwari, Shriram (1991). The Mandal Commission and Mandalisation: A Critique. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 18–26. ISBN 9788170223382.

- "Redesigning reservations: Why removing caste-based quotas is not the answer".

- "Mandal Commission" (PDF). simplydecoded.com.

- Agrawal, S. P.; Aggarwal, J. C. (1991). Educational and Social Uplift of Backward Classes: At what Cost and How? : Mandal Commission and After. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 59–60. ISBN 9788170223399.

- "BC, DC or EC? What lies ahead of the census- hazard lists and multiple definitions could pose hurdles in establishing identity during the caste count".

- "OBCs: Who are they?-Reservation policy for OBCs: Who would benefit and what are the costs involved". Retrieved 17 July 2006.

- "Time to curb number of backward castes".

- "The Muslim OBCs And Affirmative Action-SACHAR COMMITTEE REPORT".

- "SECC 2011: Why we are headed for Mandal 2 and more quotas before 2019".

- Ramaiah, A (6 June 1992). "Identifying Other Backward Classes" (PDF). Economic and Political Weekly: 1203–1207. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2005. Retrieved 27 May 2006.

- Mandal Commission report, Vol I, pp 23

- Mandal Commission report, Vol I, pp 31

- Mandal Commission Report, Vol. 1, Recommendations. pp. 57–60.

- Borooah, Vani Kant, author. (18 June 2019). Disparity and discrimination in labour market outcomes in India : a quantitative analysis of inequalities. ISBN 978-3-030-16263-4. OCLC 1108737729.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Parchure, Rajas (1 December 2011). "Foreword". Artha Vijnana: Journal of the Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics. 53 (4). doi:10.21648/arthavij/2011/v53/i4/117540. ISSN 0971-586X.

- "How VP Singh Stirred a Hornet's Nest With the Mandal Commission". The Quint. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- Guha, Ramchandra (2017). India After Gandhi: 10th Anniversary Edition. New Delhi: Picador India. pp. 602–604. ISBN 9789382616979.

- "Case analysis of Indira Sawhney v. UOI". Legal Bites - Law And Beyond. 15 September 2016. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- "20 years after Mandal, less than 12% OBCs in central govt jobs - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- "Mandal vs Mandir".

- "The Telegraph - Calcutta : Frontpage". www.telegraphindia.com. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- Kumar, Anu (29 September 2012). "Mandal memories". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- Negi, S.S. (10 June 2006). "Reply to SC daunting task for government". The Tribune. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- Anand, Arun (24 May 2007). "What is India's population of other backward classes?". Yahoo! News India. Archived from the original on 27 June 2007.

- "36% population is OBC, not 52%". Business Standard News. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- http://www.catchnews.com/india-news/let-s-have-an-index-to-measure-how-disadvantaged-an-individual-is-yogendra-yadav-1439668620.html

- 36% population is OBC, not 52% Archived 18 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. South Asian Free Media Association (8 May 2006). Retrieved on 27 May 2006.

- "Mandal's True Inheritors". The Times of India. 12 December 2006. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- "Population". Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 26 May 2006. Retrieved 27 May 2006.

- "36% population is OBC, not 52%". South Asian Free Media Association. 8 May 2006. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2006.

- Ramaiah, A (6 June 1992). "Identifying Other Backward Classes" () pp. 1203–1207. Economic and Political Weekly. URL accessed on 5 December 2013.

- Complete Text of the Mandal Commission Report

External links

- Reserving the deserving, genesis of a debate

- The Skimming of the creamy layer

- Countercurrents

- Youth for Equality

- Diluting Mandal from S.S.Gill, Secretary, Mandal Commission.

- Supporting reservations

- Late Mr Rajiv Gandhi's Speech on Mandal Commission