Double-banded plover

The double-banded plover (Charadrius bicinctus), known as the banded dotterel or pohowera in New Zealand, is a species of bird in the plover family.[2] Two subspecies are recognised: the nominate Charadrius bicinctus bicinctus,[3] which breeds throughout New Zealand, including the Chatham Islands, and Charadrius bicinctus exilis,[4] which breeds in New Zealand's subantarctic Auckland Islands.

| Double-banded plover | |

|---|---|

| |

| Breeding plumage | |

| |

| Non-breeding plumage | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Charadriidae |

| Genus: | Charadrius |

| Species: | C. bicinctus |

| Binomial name | |

| Charadrius bicinctus | |

Taxonomy

A 2015 study found its closest relatives to be other plovers found in New Zealand, the New Zealand plover or New Zealand dotterel (Charadrius obscurus) and the wrybill (Anarhynchus frontalis), which the study found to be in the Charadrius clade.[5]

Description

The double-banded plover is distinguished by a dark, grey-brown back with a distinctive white chest and a thin band of black situated just below the neck running across the chest along with a larger brown band underneath. During breeding season, these bands are more dominantly shown on the males compared to females.[3] Younger birds have no bands, and are often speckled brown on top, with less white parts. These shorebirds have relatively long legs to allow them to easily wade around shallow waters and move efficiently around sandy beaches. Their long- pointed wings aid in traveling long distances as they allow the bird to be very agile.[6] The double-banded plovers' head is prominent with their large, dark-brown eyes and sturdy black bills. Due to similar colors within the plovers ideal habitat, spotting these birds can be difficult to achieve however, the "chirp-chirp" call is easily heard and their habit of running quickly then pausing to feed on food can catch the eye of observers.[2]

Distribution

Range

This species is predominantly found in New Zealand as this country holds these birds’ main nesting sites, however, they are partly migratory, with some dotterels’ that nest in South Island riverbeds and outwash fans from the high country, generally migrate to winter in Australia, New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Fiji along with various other tropic countries.[7] Other lowland and central southern birds move to different areas around New Zealand.[8] Each bird will return to New Zealand to breed and for nesting season.

Banded dotterels are spread throughout New Zealand however, they are more commonly located around northland coastal areas and around near off shore islands, as well as dense population located on Stewart Island.[7] They are located sparsely on the west coast around Taharoa to the North Cape with a few isolated pairs found around Taranaki.[9] Populations distributed throughout the Auckland and Chatham Islands have been observed to only travel locally throughout the year, whereas birds located on the mainland around high country outwash fans in the South Island generally commence migrations of hundreds of kilometres to Australia.[10] Birds that don't migrate out of New Zealand tend to breed in the lower areas of the South Island along with central rivers and have been recorded to commonly move north to winter along coastal areas of the northern area in the North Island.[11] Other dotterels that already breed on northern coastal lagoons and beaches sometimes only move a few kilometres away.[10]

Habitat preferences

Northern populations of double-banded plover are commonly found to have inhabited sandy beaches and sandpits as well as few pairs accustoming to shell banks in harbours with few found on gravel beaches and nesting sites generally found clustered around stream-mouths.[12] During the breeding periods, males create numerous nests constructed on open patches of slightly elevated sand or on shells and occasionally in cushion plants which are all mostly padded with various materials retrieved from close by.[13] Birds found in the southern parts of New Zealand, such as Stewart Island, prefer to breed on unprotected sub-alpine and stony areas but become coastal during off-breeding months where they feed around the beach areas. Braided rivers are also an ideal habitat preferred by many dotterels around the Canterbury areas.[14]

Behaviour

Breeding

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Around the month of July in New Zealand, the banded dotterels enter the breeding season, more commonly in the South Island or southern areas of the North Island such as Hawke's Bay, Marlborough, Kaikoura Peninsula, Canterbury, Otago, Stewart Island etc.[15] These birds form seasonal monogamous pairs where once a partner is found, they remain with that one bird for the rest of the breeding season to help raise the young.[16] During this time, the male grows colored bands on his chest prior to the beginning of the breeding season and later females are attracted by the loud calls of the male where they are then presented with several nests which they can choose between while the male puts on a defensive display, protecting his territory, where it flies towards any possible intruder in a fast butterfly-like circular motion flight.[16] This species usually constructs nests upon slightly elevated, open patches on the sand, shells or sometimes hollows in cushion plants or between rocks which are broadly padded with various materials such as tussock tillers, smaller stones and shells, grass, lichen, moss, twigs etc.[15]

There can be several hundred birds in one area during this season. From August to September, the dotterels lay two to four eggs and can relay up to three times if there is a failure or predation. Incubation of these eggs generally takes 28–30 days where the young fledging period extends to around six weeks.[16]

Banded dotterel chicks leave their nests upon the day of hatching where they accompany their parents in the hunt for food.[17] At the slimmest indication of potential danger, watchful adult birds sound the alarm causing the chicks to run a few feet in a scattered motion then squat with their legs doubled over beneath them and their head stretched out firmly against the ground in front of them, camouflaging into the coastal terrain around them.[18] They remain stationed without moving until the parents decide the surrounding environment is clear and safe to move again. Unlike the young of most bird species, these chicks will be reliant to feed themselves with parents guarding close by for five to six weeks until they fledge. The parents will then stay close by for several days until the chicks join flocks and become fully independent.[18]

Both of the parents continue to tend their young for another two weeks when birds have grown their contour feathers and the birds all part ways. Some of these birds migrate overseas to nearby countries such as southern Australia, Tasmania or other tropic countries.[19] Other dotterels fled to the northern areas of New Zealand in groups alongside many other adult banded dotterels and newly fledged chicks. A high percentage of all off-spring return to the breeding grounds for mating within their first year, however the rest of the generation return in their second year.[15]

Feeding

Double-banded plovers are predominantly opportunistic carnivores, feeding on aquatic invertebrates and other insects along the coast lines or rivers. They have also been known to consume berries off various nearby shrubs such as Coprosma and Muehlenbeckia.[14]

These birds forage both within the day time and at night using different techniques for both.[20] During the day, plovers were seen spending greater amounts of time flying and more time standing alert and watchful. The birds were observed to walk, peck, run, forage, and groom both day and night, however during the day the amount of paces walked was much greater than movement at night as the birds would spot insect movement and move at a fast pace to the area to peck before moving off again.[20]

During the night, double-banded plovers were noted to have a repeated pecking techniques and spent a lot more time waiting in one area suggesting that the plovers were trying to use the nearby vicinity to catch prey in due to the fact that prey detection distances would have been significantly reduced in lack of light.[21] This reduction of paces during the night causes prey to find it more difficult to detect the stilled birds which increases the ability of the plovers to be able to detect their prey and decreases the chance that prey could be unnoticed.

Birds located on breeding grounds were commonly found to have a more varied diet containing insect larvae, spiders, beetles, aquatic insects such as caddisflies, stoneflies and mayflies along with terrestrial flies.[22] The contents of various fecal samples from plovers included flies, adult beetles and bugs while results from New Zealand Dotterel birds tested on the Canterbury riverbeds showed large amounts of fruits of Coprosma petrei and Mueblenbeckia axillaris.[14]

Predators, parasites and diseases

Being a ground-based nesting bird, many dangers arise through predation due to the introduction of mammalian predators that were introduced to New Zealand, human impacts that can cause habitat loss and various parasites that can target these birds.

Hedgehogs are a common predator that pose a serious threat to the banded dotterels as they have ravenous appetites and are known to eat the eggs and chicks of these ground-nesting birds.[23] These creatures can move up to two kilometers each night causing a number of these birds to be in danger from attacks in the area.

Other mammals also pose a major threat to these incubating birds as uncontrolled dogs moving through nesting areas cause eggs to be crushed and disturbance among nesting birds can be detrimental.[24] Cats and stoats also prey on these ground-based birds and fledglings.

In one case, 41 nests were monitored in New Zealand where of the 16 nests that failed to hatch, eight of these were flooded.[25]

Feather mites (Brephosceles constrictus) can also pose a threat to the health of these birds as they feed predominantly on the blood of the bird along with feathers, skin or scales taking up to two hours. This can lead to increased levels of stress resulting in anemia, decreased egg production and in some cases, death.[24]

Hunting and conservation

Prior to 1908, banded dotterels in New Zealand were shot in large numbers by market gunners upon the return of these migrating birds for breeding.[19] However, in 1908, the banded dotterels were placed on the protected list, prohibiting any more shootings from occurring to the point where they are now moderately common.[17]

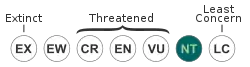

In 2013 local Maori in the Pencarrow Coast, Wellington region, placed a rahui on the area, to protect 20 pairs of banded dotterel from dogs and cars.[26] This species has the conservation status of "Regionally Vulnerable" in the Wellington region.[27] The species is classified as Near Threatened.[1]

A double-banded plover nest

A double-banded plover nest Double-banded plover eggs

Double-banded plover eggs

References

- BirdLife International (2020). "Charadrius bicinctus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hutching, G. "Wading birds- Dotterels". TeAra.

- "Specimens of Charadrius bicinctus bicinctus". Collections Online. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- "Holotype of Charadrius bicinctus exilis". Collections Online. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- dos Remedios, Natalie; et al. (2015). "North or south? Phylogenetic and biogeographic origins of a globally distributed avian clade" (PDF). Phylogenetics and Evolution. 89: 151–159. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2015.04.010. PMID 25916188.

- Pierce, R (1999). "Regional patterns of migration in the banded dotterel Caradrius bictinctus". Notornis. 46: 101–122.

- Heather, B; Robertson, H. "Banded dotterel". New Zealand Birds Online.

- Dowding, J; Moore, S (2006). "Habitat networks of indigenous shorebirds in New Zealand" (PDF). Science for Conservation. 261: 99.

- Pierce, R (1999). "Regional patterns of migration in the banded dotterel Charadrius bicinctus". Notornis. 46: 101–122.

- Heather, B; Robertson, H (2013). "Banded dotterel". New Zealand Birds Online.

- Remedios, N (2015). "North or South? Phylogenetic and biogeographic origins of a globally distributed avian clade" (PDF). Phylogenetics and Evolution. 89: 151–159. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2015.04.010. PMID 25916188.

- Dowding, J; Moore, S (2006). "Habitat networks of indigenous shorebirds in New Zealand" (PDF). Science for Conservation. 261: 99.

- Pierce, R (1989). "Breeding and social patterns of banded dotterels (Charadrius bicinctus) at Cass River". Notornis. 36: 13–23.

- Hughey, K. Hydrological factors influencing the ecology of riverbed breeding birds on the plains' reaches of Canterbury's braided rivers (Ph.D Thesis). New Zealand: University of Canterbury. p. 225. hdl:10182/1639.

- Rebergen, A; Keedwell, R; Moller, H; Maloney, R (1998). "Breeding success and predation at nests of banded dotterel (Charadrius bictinctus) on braided riverbeds in central South Island, New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 22: 33–41.

- Fleming, C; Bull, P (1940). "Banded Dotterel (Charadrius bincinctus)" (PDF). Notornis. 1 (1): 27–30.

- Oliver, N (2000). Pohowera; the banded dotterel. Field Guide to the Birds of New Zealand. p. 6.

- Bomford, M. The behavior of the Banded Dotterel, Charadrius bicinctus. Dunedin, New Zealand: University of Otago.

- Heather, B; Robertson, H. "Banded dotterel". New Zealand birds online.

- Rohweder, D; Lewis, B (2002). "Night-day habitat use by banded dotterels ( Charadrius bicinctus ) in the Richmond River Estuary, northern NSW". Notornis. 51 (3): 141–146.

- Dann, P (1991). "Feeding behaviour and diet of banded dotterels Charadrius bicinctus in Western Port, Victoria". Emu. 91 (3): 179–184. doi:10.1071/mu9910179.

- Hughey, K (1997). "The diet of the Wrybill (Anarhynchus frontalis) and the Banded Dotterel (Charadrius bicinctus) on two braided rivers in Canterbury, New Zealand". Notornis. 44: 785–19.

- Dowding, J; Moore, S (2006). Science for Conservation. pp. 47–64.

- Sanders, M; Maloney, R (2002). Causes of mortality at nests of ground-nesting birds in the Upper Waitaki Basin, South Island, New Zealand. pp. 225–236.

- Cruz, J; Seddon, P; Cleland, S; Nelson, D; Sanders, M; Maloney, R (2013). "Species-specific responses by ground-nesting Charadriiformes to invasive predators and river flows in the braided Tasman River of New Zealand". Biological Conservation. 167: 363–370. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2013.09.005.

- Restrictions in place to protect rare bird. 3 News NZ. 3 October 2013.

- McArthur, Nikki; Ray, Samantha; Crowe, Patrick; Bell, Mike (August 2019). A baseline survey of the indigenous bird values of the Wellington region coastline (PDF) (Report). p. 9.

- Stephen Marchant (Editor), P. J. Higgins (Editor) (1994) Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds: Volume 2: Raptors to Lapwings. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-553069-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charadrius bicinctus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Charadrius bicinctus. |