Pepin the Short

Pepin the Short[lower-alpha 1] (German: Pippin der Jüngere, French: Pépin le Bref, c. 714 – 24 September 768) was the King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first of the Carolingians to become king.[lower-alpha 2][2]

| Pepin the Short | |

|---|---|

Pepin the Short, miniature, Anonymi chronica imperatorum, c. 1112–1114 | |

| King of the Franks | |

| Reign | 751 – 24 September 768 |

| Predecessor | Childeric III |

| Successor | Charlemagne and Carloman I |

| Mayor of the Palace of Neustria | |

| Reign | 741–751 |

| Predecessor | Charles Martel |

| Successor | Merged into crown |

| Mayor of the Palace of Austrasia | |

| Reign | 747–751 |

| Predecessor | Carloman |

| Successor | Merged into crown |

| Born | 714 |

| Died | 24 September 768 (aged 54) Saint-Denis |

| Burial | Basilica of St Denis |

| Spouse | Bertrada of Laon |

| Issue | Charlemagne Carloman I Gisela |

| Dynasty | Carolingian |

| Father | Charles Martel |

| Mother | Rotrude of Hesbaye |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Signature | |

The younger son of the Frankish prince Charles Martel and his wife Rotrude, Pepin's upbringing was distinguished by the ecclesiastical education he had received from the monks of St. Denis. Succeeding his father as the Mayor of the Palace in 741, Pepin reigned over Francia jointly with his elder brother Carloman. Pepin ruled in Neustria, Burgundy and Provence, while his older brother Carloman established himself in Austrasia, Alemannia and Thuringia. The brothers were active in suppressing revolts led by the Bavarians, Aquitanians, Saxons and the Alemanni in the early years of their reign. In 743, they ended the Frankish interregnum by choosing Childeric III, who was to be the last Merovingian monarch, as figurehead king of the Franks.

Being well disposed towards the church and papacy on account of their ecclesiastical upbringing, Pepin and Carloman continued their father's work in supporting Saint Boniface in reforming the Frankish church, and evangelising the Saxons. After Carloman, who was an intensely pious man, retired to religious life in 747, Pepin became the sole ruler of the Franks. He suppressed a revolt led by his half-brother Grifo, and succeeded in becoming the undisputed master of all Francia. Giving up pretense, Pepin then forced Childeric into a monastery and had himself proclaimed king of the Franks with support of Pope Zachary in 751. The decision was not supported by all members of the Carolingian family and Pepin had to put down a revolt led by Carloman's son, Drogo, and again by Grifo.

As king, Pepin embarked on an ambitious program to expand his power. He reformed the legislation of the Franks and continued the ecclesiastical reforms of Boniface. Pepin also intervened in favour of the papacy of Stephen II against the Lombards in Italy. He was able to secure several cities, which he then gave to the Pope as part of the Donation of Pepin. This formed the legal basis for the Papal States in the Middle Ages. The Byzantines, keen to make good relations with the growing power of the Frankish empire, gave Pepin the title of Patricius. In wars of expansion, Pepin conquered Septimania from the Islamic Umayyads, and subjugated the southern realms by repeatedly defeating Waiofar and his Gascon troops, after which the Gascon and Aquitanian lords saw no option but to pledge loyalty to the Franks. Pepin was, however, troubled by the relentless revolts of the Saxons and the Bavarians. He campaigned tirelessly in Germany, but the final subjugation of these tribes was left to his successors.

Pepin died in 768 and was succeeded by his sons Charlemagne and Carloman. Although unquestionably one of the most powerful and successful rulers of his time, Pepin's reign is largely overshadowed by that of his more famous son, Charlemagne.

Assumption of power

Pepin's father Charles Martel died in 741. He divided the rule of the Frankish kingdom between Pepin and his elder brother, Carloman, his surviving sons by his first wife: Carloman became Mayor of the Palace of Austrasia, Pepin became Mayor of the Palace of Neustria. Grifo, Charles's son by his second wife, Swanahild (also known as Swanhilde), demanded a share in the inheritance, but he was besieged in Laon, forced to surrender and imprisoned in a monastery by his two half-brothers.

In the Frankish realm the unity of the kingdom was essentially connected with the person of the king. So Carloman, to secure this unity, raised the Merovingian Childeric to the throne (743). Then in 747 Carloman either resolved to or was pressured into entering a monastery. This left Francia in the hands of Pepin as sole mayor of the palace and dux et princeps Francorum.

At the time of Carloman's retirement, Grifo escaped his imprisonment and fled to Duke Odilo of Bavaria, who was married to Hiltrude, Pepin's sister. Pepin put down the renewed revolt led by his half-brother and succeeded in completely restoring the boundaries of the kingdom.

Under the reorganization of Francia by Charles Martel, the dux et princeps Francorum was the commander of the armies of the kingdom, in addition to his administrative duties as mayor of the palace.[3]

First Carolingian king

As mayor of the palace, Pepin was formally subject to the decisions of Childeric III who had only the title of king but no power. Since Pepin had control over the magnates and actually had the power of a king, he now addressed to Pope Zachary a suggestive question:

- In regard to the kings of the Franks who no longer possess the royal power: is this state of things proper?

Hard pressed by the Lombards, Pope Zachary welcomed this move by the Franks to end an intolerable condition and lay the constitutional foundations for the exercise of the royal power. The Pope replied that such a state of things is not proper. In these circumstances, the de facto power was considered more important than the de jure authority.

After this decision the throne was declared vacant. Childeric III was deposed and confined to a monastery. He was the last of the Merovingians.

Pepin was then elected King of the Franks by an assembly of Frankish nobles, with a large portion of his army on hand. The earliest account of his election and anointing is the Clausula de Pippino written around 767. Meanwhile, Grifo continued his rebellion, but was eventually killed in the battle of Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne in 753.

Pepin was assisted by his friend Vergilius of Salzburg, an Irish monk who probably used a copy of the "Collectio canonum Hibernensis" (an Irish collection of canon law) to advise him to receive royal unction to assist his recognition as king.[4] Anointed a first time in 751 in Soissons, Pepin added to his power after Pope Stephen II traveled all the way to Paris to anoint him a second time in a lavish ceremony at the Basilica of St Denis in 754, bestowing upon him the additional title of patricius Romanorum (Patrician of the Romans) and is the first recorded crowning of a civil ruler by a Pope.[5] As life expectancies were short in those days, and Pepin wanted family continuity, the Pope also anointed Pepin's sons, Charles (eventually known as Charlemagne), who was 12, and Carloman, who was 3.

Expansion of the Frankish realm

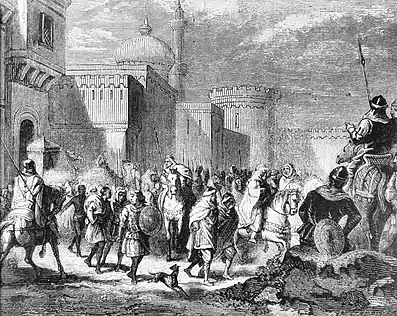

.jpg.webp)

Pepin's first major act as king was to go to war against the Lombard king Aistulf, who had expanded into the ducatus Romanus. After a meeting with Pope Stephen II at Ponthion, Pepin forced the Lombard king to return property seized from the Church.[6] He confirmed the papacy in possession of Ravenna and the Pentapolis, the so-called Donation of Pepin, whereby the Papal States were established and the temporal reign of the papacy officially began.[6] At about 752, he turned his attention to Septimania. The new king headed south in a military expedition down the Rhone valley and received the submission of eastern Septimania (i.e. Nîmes, Maguelone, Beziers and Agde) after securing count Ansemund's allegiance. The Frankish king went on to invest Narbonne, the main Umayyad stronghold in Septimania, but could not capture it from the Iberian Muslims until seven years later in 759,[7] when they were driven out to Hispania.

Aquitaine still remained under Waiofar's Gascon-Aquitanian rule, however, and beyond Frankish reach. Duke Waiofar appears to have confiscated Church lands, maybe distributing them among his troops. In 760, after conquering the Roussillon from the Muslims and denouncing Waiofar's actions, Pepin moved his troops over to Toulouse and Albi, ravaged with fire and sword most of Aquitaine, and, in retaliation, counts loyal to Waiofar ravaged Burgundy.[8] Pepin, in turn, besieged the Aquitanian-held towns and strongholds of Bourbon, Clermont, Chantelle, Bourges and Thouars, defended by Waiofar's Gascon troops, who were overcome, captured and deported into northern France with their children and wives.[9]

In 763, Pepin advanced further into the heart of Waiofar's domains and captured major strongholds (Poitiers, Limoges, Angoulême, etc.), after which Waiofar counterattacked and war became bitter. Pepin opted to spread terror, burning villas, destroying vineyards and depopulating monasteries. By 765, the brutal tactics seemed to pay off for the Franks, who destroyed resistance in central Aquitaine and devastated the whole region. The city of Toulouse was conquered by Pepin in 767 as was Waiofar's capital of Bordeaux.[10]

As a result, Aquitanian nobles and Gascons from beyond the Garonne too saw no option but to accept a pro-Frankish peace treaty (Fronsac, c. 768). Waiofar escaped but was assassinated by his own frustrated followers in 768.

Legacy

Pepin died during a campaign, in 768 at the age of 54. He was interred in the Basilica of Saint Denis in modern-day Metropolitan Paris. His wife Bertrada was also interred there in 783. Charlemagne rebuilt the Basilica in honor of his parents and placed markers at the entrance.

The Frankish realm was divided according to the Salic law between his two sons: Charlemagne and Carloman I.

Historical opinion often seems to regard him as the lesser son and lesser father of two greater men, though a great man in his own right. He continued to build up the heavy cavalry which his father had begun. He maintained the standing army that his father had found necessary to protect the realm and form the core of its full army in wartime. He not only contained the Iberian Muslims as his father had, but drove them out of what is now France and, as important, he managed to subdue the Aquitanians and the Gascons after three generations of on-off clashes, so opening the gate to central and southern Gaul and Muslim Iberia. He continued his father's expansion of the Frankish church (missionary work in Germany and Scandinavia) and the institutional infrastructure (feudalism) that would prove the backbone of medieval Europe.

His rule, while not as great as either his father's or son's, was historically important and of great benefit to the Franks as a people. Pepin's assumption of the crown, and the title of Patrician of Rome, were harbingers of his son's imperial coronation which is usually seen as the founding of the Kingdom of France. He made the Carolingians de jure what his father had made them de facto—the ruling dynasty of the Franks and the foremost power of Europe. Known as a great conqueror, he was undefeated during his lifetime.

Family

Pepin married Leutberga from the Danube region. They had five children. She was repudiated some time after the birth of Charlemagne and her children were sent to convents.

In 741, Pepin married Bertrada, daughter of Caribert of Laon. They are known to have had eight children, at least three of whom survived to adulthood:

Notes

- Rarely his name may be spelled "Peppin".

- He wore his hair short, in contrast to the long hair that was a mark of his predecessors.[1]

References

- Dutton 2008, p. ?.

- Riché 1993, p. 65.

- Schulman 2002, p. 101.

- Enright 1985, p. ix, 198.

- The Oxford dictionary of Byzantium. Kazhdan, A. P. (Aleksandr Petrovich), 1922-1997,, Talbot, Alice-Mary Maffry,, Cutler, Anthony, 1934-, Gregory, Timothy E.,, Ševčenko, Nancy Patterson. New York: Oxford University Press. 1991. ISBN 0195046528. OCLC 22733550.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Brown 1995, p. 328.

- Lewis 2010, p. chapter 1.

- Petersen 2013, p. 728.

- Petersen 2013, pp. 728–731.

- Tucker 2011, p. 215.

Further reading

- Brown, T.S. (1995). "Byzantine Italy". In McKitterick, Rosamond (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History, c.700-c.900. Vol. II. Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dutton, Paul Edward (2008). Charlemagne's Mustache: And Other Cultural Clusters of a Dark Age. Palgrave Macmillan.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Enright, M.J. (1985). Iona, Tara, and Soissons: The Origin of the Royal Anointing Ritual. Walter de Gruyter.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lewis, Archibald R. (2010). The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society, 718–1050. THE LIBRARY OF IBERIAN RESOURCES ONLINE.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Petersen, Leif Inge Ree (2013). Siege Warfare and Military Organization in the Successor States (400-800 AD): Byzantium, the West and Islam. Leiden: Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-25199-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Riché, Pierre (1993). The Carolingians: A Family Who Forged Europe. Translated by Allen, Michael Idomir. University of Pennsylvania Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schulman, Jana K., ed. (2002). The Rise of the Medieval World, 500-1300: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2011). A Global Chronology of Conflict. Vol. I. ABC-CLIO.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pepin the Short. |

- Literatur über Pippin den Jüngeren in the German National Library catalogue

- Document by Pepin for Fulda Abbey, 760, "digitalised image". Photograph Archive of Old Original Documents (Lichtbildarchiv älterer Originalurkunden). University of Marburg..

Pepin the Short Born: 714 Died: 768 | ||

| Preceded by Charles Martel |

Mayor of the Palace of Neustria 741–751 |

Merged into crown |

| Preceded by Carloman |

Mayor of the Palace of Austrasia 747–751 | |

| Preceded by Childeric III |

King of the Franks 751 – 24 September 768 |

Succeeded by Charles I and Carloman I |