Early Middle Ages in Azerbaijan

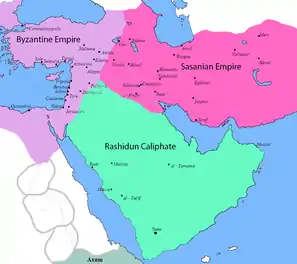

In the history of Azerbaijan, the Early Middle Ages lasted from the 3rd century to the 11th century. This period in the territories of today's Azerbaijan Republic begins with the incorporation of these territories into the Sasanian Persian Empire in the 3rd century AD. Feudalism started to shape in Azerbaijan in the Early Middle Ages. The territories of Caucasian Albania became an arena of wars between the Byzantine Empire and the Sassanid Empire. After the fall of the Sassanid Empire by the Arab Caliphate, Albania also weakened, and in 705 AD it was overthrown by the Abbasid Caliphate under the name of Arran. As the control of the Arab Caliphate over the Caucasus region weakened, independent states began to emerge in the territory of Azerbaijan.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Sassanid conquest

History

Around 227 AD Atropatene, and in 252-253 AD, Caucasian Albania were conquered and annexed by the Sassanid Empire. Atropatene was included to the Sassanid's north marzbans and Albania became a vassal state of the Sassanid Empire, but retained its monarchy; the Albanian king had no real power and most civil, religious, and military authority lay with the Sassanid marzban (military governor) of the territory. After Sassanids’ victory over Romans in 260 AD, this victory, as well as, the annexation of Albania and Atropatene were described in the trilingual inscription of Shapur I at the Ka’be-ye Zartošt at Naqš-e Rostam.[7][3][8][9][10][11][12][13][14]

Relative of Sasanian Shapur II (309-379), Urnayr was brought to power in Albania (343-371), and he followed a partially independent policy in foreign policy, Urnayr allied with the Sasanian king Shapur II. According to Ammianus Marcellinus, the Albanians provided military forces (especially cavalry) to the Shapur II armies in their attacks against the Romans, especially during the siege of Amida (359), which ended with the victory of the Sassanid army and as a result, Arsakh, Marlar (now Nakhichevan), Caspiana and other regions of Albania were returned. He also noted that the Albanian cavalry was to play a determinative role in the siege of Amida, like the Chionites (Xionites). The Albanians received an honorary degree for being Shapur's military ally. After this victory, king Shapur II started to oppress the Christian religion in Albania.[7][10][9][15]

“Close by him [Šapur II] on the left went Grumbates, king of the Chionitae, a man of moderate strength, it is true, and with shrivelled limbs, but of a certain greatness of mind and distinguished by the glory of many victories. On the right was the king of the Albani, of equal rank, high in honour”.[16]

In 371, the battle of Dzirav (also known as the battle of Bagavan) took place between the Romans and Sassanid armies. Albania was the Sassanid's ally in this battle too. The battle resulted in the victory of the Roman army. Urnayr was wounded and Albania was deprived of provinces like Uti, Shakashena (Sakasena), Colt (Albania's western border province) and Girdiman valley in this battle. Albania returned its lost provinces with the deal signed between Rome and Sasanids in 387.[6][5][17]

In 450, the Sasanian army was defeated by the insurgents of Christian faith against Persian Zoroastrianism of King Yazdegerd II in the battle near the city of Khalkhal (present Gazakh region) and Albania was cleaned from Persian garrisons. After the death of Yazdegerd II, an intensive fight began for the throne in Iran between Yazdegerd's sons Hormuzd and Peroz. The return to Christianity of Vache II resulted in a war between Persia and Caucasian Albania and Vache II declared his recalcitrancy to new Sasanian ShahenShah Peroz. After this distrust, Peroz raised the Haylandur (Onoqur) Huns to fight the Albanian monarch. They occupied Albania in 462. This fight ended with getting off the throne of Vache II in 463. M. Kalankatli wrote that Albania has remained without a ruler for 30 years. The northern part of Azerbaijan was turned into marzbanianity of Sasanian Empire.[8]

According to M. Kalankatli, almost, 30 years later, the monarchy of local rulers was reestablished in Albania by the nephew of II Vache- Vachagan III-(487-510). Vachagan Barepaš (pious) was admitted to the throne by Sassanid shah Balash (Valarsh) (484-488). Vachagan III restored the concessions of the Albanian tsars, reduced taxes, and granted freedoms to Christians.[8][18]

Independent state institutions were eliminated in the South Caucasus by Sassanids in 510. Governor-generals of Sassanid began a long period (510-629) of domination in Albania.[5][6]

In the late 6th to early 7th centuries, the territory of Albania became an arena of wars between Sassanid Persia, Byzantium, and the Khazar Khanate, the latter two very often acting as allies against Sassanid Persia. In 628, during the Third Perso-Turkic War, the Khazars invaded Albania, and their leader Ziebel declared himself Lord of Albania, levying a tax on merchants and the fishermen of the Kura and Araxes rivers "in accordance with the land survey of the kingdom of Persia".[5][8]

The reign of the Mihranids dynasty (630-705) arrived in Albania in the early 7th century. This dynasty originated from Girdiman province (now Shamkir-Gazakh region of Azerbaijan) of Albania. Partav (now Barda) was the centre of this dynasty. According to M. Kalankatli, initiator of the Mehranids’ dynasty was Mehran (570-590), and the representative was Varaz Grigor (628-642) who took the title of “prince of Albania”.[5][8]

Partav (Berde) was the capital city of Albania during the reign of Varaz Grigor's son Javanshir (642-681). Javanshir showed his obedience to the Sassanid shah Yazdegerd III (632-651) in the first period of his reign. He was the head of Albanian army as sparapet and alliance of Yazdegerd III in the years of 636–642. Despite the Arab victory in the battle of Kadissia in 637, Javanshir fought as an ally of the Sassanids. After the fall of the Sassanid Empire by the Arab Caliphate in 651, Javanshir changed his policy and moved to Byzantine emperor's side in 654. Konstantin II took Javanshir under his protection. Javanshir became a ruler of the Albanian country thanks to the protection of Byzantium. In 662, Javanshir defeated the Khazars near the Kura River. Three years later (665), the Khazars attacked again Albania with greater force and won. According to the agreement signed between Javanshir and the head of the Khazars, the Albanians agreed to pay tribute every year. In return, the Khazars returned all the captives and looted cattle. The Albanian ruler established diplomatic relations with the Caliphate in order to protect his country from the invasion of the Caspian Sea. For this purpose, he went to Damascus and met with the caliph Muaviya (667, 670). As a result, the caliphate did not touch Albania's internal independence, and at the request of Javanshir, Albania's taxes were reduced by a third. Javanshir was assassinated in 681 by Byzantine feudal lords. After his death, the Khazars attacked and plundered Albania again. Arab troops entered Albania in 705 and took Javanshir's last heir to Damascus and put him to death. Thus, the rule of the Mihrani dynasty ended in Albania. Albania's internal independence was abolished. Albania started to be ruled by the Caliph's successor.[19][20][21][22]

Religion

According to local tradition, Christianity entered Caucasian Albania in the 1st century through St. Elisæus of Albania, a disciple of St. Thaddeus of Edessa. The first Christian church in South Caucasus was established in Caucasian Albania by St. Elishe in the village of Kish in the region of Uti (now Sheki district, north-western Azerbaijan).[23][24]

This church was regarded by Caucasian Albanians as their "mother church" which laid the foundation of institutionalized Christianity in the kingdom. At the beginning of the IV century, monophysite Albanian church became a state institution as an apostolic church. In the reign of king Uṙnayr who was baptized by St. Gregory, Caucasian Albania officially adopted Christianity and it started to gradually spread. According to the Azerbaijani historian Ismail bey Zerdabli, during the reign of Sasanian emperor Yazdegerd I (399-420), Albanian church was developed, and a lot of concessions were given to them. On the contrary, due to Yazdegerd II’s attempts to strengthen royal centralisation in the bureaucracy by imposing Zoroastrianism on the Christians within the country, Zoroastrianism became spread between Albanians. Moisey Klankatlu wrote that “strict order of the ShahenShah obliged us to stop worshipping our religion and accept pagan religion of mags”.[8][25][5][26][10]

In the mid-5th century, under Albanian king Vache II (440-463) - nephew of Yazdegerd II, Caucasian Albania refused Christianity and adopted Zoroastrianism because of the Persian influence. In Albania, Christian churches were turned into temples, and Christianity was severely persecuted.[27][7][23]

After Yazdagerd II died in 457, Vache II changed his internal policy. He rejected the Zoroastrianism religion and returned to Christianity. By extending Christianity to Albania, his goal was to get rid of the Sassanid rule.[28][5]

In the monarchy of Vachagan III, in 498, in the settlement named Aluen (Aghuen) (present day Agdam region of Azerbaijan), an Albanian church council convened to adopt laws further strengthening the position of Christianity in Albania. During the council, a twenty-one-paragraph codex formalizing and regulating the important aspects of the Church's structure, functions, relationship with the state, and legal status was adopted. Vachagan III took an active part in Christianizing Caucasian Albanians and appointing clergy to monasteries throughout his kingdom.[8][5]

Socio-economic and cultural life

During the Sassanid period, two types of land ownership in Albania and Atropatene were common: hereditary land ownership- Dastgerd and conditional land ownership- Khostak. Dastgerd formed at the result of the collapse of communal land ownership, was distributed among the representatives of the ruling class by the state. Khostak was given to feudal aristocracy in exchange for their vassal services. In Albania, the position of community land ownership was also strong. Free peasants with community land have existed here for a long time. Community peasants paid taxes to the ruler's treasury and performed certain duties. In Atropatene, the population divided into four sections: priests, military officers, scribes, and taxpaying class.[29][30][31][32]

In the 5th and 6th centuries, the formation of the feudal class in Albania was completed: this class was expressed in many different terms, mainly "azat" and "naharar", which corresponded to the peasants-shinakan. The naharars were tax-free. Their main task was military service to the ruler, and at first, they ruled entire provinces or districts. During the reign of Khosrow I (512-514), all men aged 20–50 were taxed in Azerbaijan, except for priests, scribes, aristocracy, and officers.[8][32]

In the early medieval ages, there were many defence fortress and hurdles in the territory of Azerbaijan. Shirvan wall was constructed along the river Gilgil, 23 kilometers to the north from Beshbarmag wall. Beshbarmag wall began from the shore of the Caspian Sea and lasted till Babadagh and Gilgilchay. Chiraggala was situated on the top of the mountain in the Guba Forest. Another hurdle was built on the north side of the river Saumur. Fortresses like Torpaggala (on the bank of the river Alazan), Govurgala (Aghdam region), Javanshir gala (Ismailli region) and Charabkert gala (Aghdara region) were built during the Sassanid rule.[6][8]

Arab conquest

History

After the battles of Jalula (637), Nahavand and Hamadan in 642 between the Arab-Sassanids, the Arabs launched attacks against Azerbaijan. According to al-Tabari, “Azerbaijan was conquered in the year of 22 of Hijri” (642-643). Defeating Sasanids in the battle of Nahavand, the Arabs opened a gateway to the province of Azerbaijan and the territory of Caucasian Albania. The Muslims then invaded Azerbaijan and drew up an agreement with the local population according to which Azerbaijan was surrendered to Caliph Umar on usual terms of paying the annual Jizya.[33]

Following years, local people rebelled against Arabs, therefore, the new Caliph Osman sent an army under the ladership of al-Walid ibn Ukba to Azerbaijan in 644–645. A new treaty with more heavy arrangements was concluded between the sides. Al-Walid sent a group of his army to the North passing the river Aras under Salman b. Rabia, and to Nakjavan (Nakhchevan) under Habib b. Maslama. Habib ended up with a treaty with the population of Nakjavan taxed to them jezya and kharaj, while the army of Salman moved to the direction of Arran, and captured Beylagan. Then, the Arabs attacked to Barda, faced here with the resistance of local people. After a while, Barda population had to conclude the treaty with Arabs. Salman continued his expedition to the left bank of the river Kura and concluded treaties with the governors of Gabala, Sheki, Shakashēn and Shirvan.[7][26][34][35][36] In 652, Bāb al-Abwāb (Darband) was conquered by the Arabs. After Darband, Salman continued his campaign through the Kazar Khaganate, however, he lost the battle and was killed. Caliphate again sent an army to the Caucasus under the leadership of Habib b. Maslam in 655.[37]

During the period of Arab invasions to Caucasus, southern parts of the territories of Azerbaijan as part of Adurbadagan completely lost its independence, while Caucasian Albania subordinated to Arabs only as vassal.[5]

Khazar-Arab wars

Due to the outbreak of the First Muslim Civil War and the priorities on other fronts, the Arabs refrained from repeating an attack on the Khazars until the early 8th century. The Khazars, on their part, only launched a few raids into the Transcaucasian principalities that were loosely under Muslim dominion: in a raid into Albania in 661/662, they were defeated by the local prince, but in 683 or 685 (also a time of civil war in the Muslim world), a large-scale raid across Transcaucasia was more successful, capturing much booty and many prisoners.[37][38][39][40]

At the beginning of the 8th century, territories of Azerbaijan was the center of the Caliphate – Khazar and Byzantine wars. In 722–723, Khazars attacked the territories of South Caucasus under the Arabs’ rules and as a result, an Arabian army led by al-Jarrah al-Hakami was swiftly successful in driving the Khazars back across the Caucasus, and fought his way north along the western coast of the Caspian Sea, recovering Derbent and advancing onto the Khazar capital of Balanjar, captured the capital of the Khazar khanate and placed prisoners around Gabala. Then al-Jarrah returned to Sheki with the booty and a large number of captives and placed his army here.[41][38][37]

In 730, after the Khazars looted many cities in Azerbaijan and defeated the Arab armies (Battle of Ardabil, 730), then the Arabs began a campaign of revenge. During the early 730s, the Arabs and Khazars were fighting over Derbent, as a result in 732, the city came into Arab control led by Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik. The Arabs again defeated Khazars in 737 and Arab forces under Marwan ibn Muhammed moved into the central parts of Khazar Khaganate passing through “the Gates of the Alans”. Marwan returned the south of the Caucasus after capturing Khazar kagan. Thus, the attempts of Khazars to control the South Caucasus were unsuccessful.[37]

Causes

Internal conflicts within the Umayyads ranks, intensification of discontent among the people under control led to a socio-political crisis in the Caliphate. In the early days of the Abbasid rule, Azerbaijan was the center of a protracted revolt against the caliphate. Abbasids’ coming to the throne in the middle of the 8th century did not facilitate the situation and life of the population in Arran and Azerbaijan. Starting from the Abbasids period, only a few part of the taxes were paid by natural means (as natura, food collected instead of currency) on the contrary to the Umayyads, while they collected all the taxes as natura.[8][42][43][44]

First rebellions

In 748, a revolt against the Umayyad dynasty took place in Beylagan under the leadership of Musafir ibn Kesir, nicknamed "al-kassab". The inspiration for this uprising was al-Dahhak ibn Qays al-Shebani, the leader of the Kharijites. The local feudal lords Ibban ibn Mansur and Hatib ibn Sadal, who were on the side of the caliphate and defended their own interests, attacked Beylagan. The rebellious inhabitants of Arran captured the fortress of Beylagan and released all the prisoners excluding the Emir. Inspired by this success, the rebels marched on Barda, crushed the Arab garrison, and assassinated the local governor, Asim ibn Yazid. The punitive army sent by the Umayyads could not repel this revolt. With the change of power in the Caliphate, the Abbasids were able to counterbalance the rebellions against the caliphate. The people of Beylagan were vanquished, the leaders of the uprisings along with Musafir were killed.[8] The locals of Shamkir revolted against the Arabic migrants who settled in the city in 752, but the Abbasids soon put down this revolt as

Khurramites and Bābak Khorramdin

The Khurramites were a religious and political movement against the Arabs Caliphate and often recognized as survival of the Zoroastrian heresy, Mazdakism. According to al-Tabari, their name first appeared in 736 when missionary Kedas of Hasemite adopted “din al-Ḵorramiya”, and after Hasemite revolution the khorramis were fought as rebels under Sonbadh, Moqanna, Babak and other different leaders in the various cities and regions.[46]

One of the researchers of the Khorrami uprising in Azerbaijani historiography, academician Z.Buniadov stated that, the peasant masses of Azerbaijan (especially in the mountainous region) maintained their pro-Islamic beliefs associated with Zoroastrianism and Mazdakism. The pretext for the revolt was that the Arabs collected most of the agricultural produce from the peasants as taxes (kharaj). The socio-economic struggle of the Khurramites was the excess of taxes and the exploitation of property. All lands were to be given to the peasants for free and cultivated together. The Khurramites tried to free the peasants from feudal dependence, to equalize state taxes and communities.[47][48]

The movement of Khurramites in Azerbaijan was associated with Javidhan who was a landlord leader of one of the two Khurramite movements in Azerbaijan (from 807–808 to 816-817), with his headquarters being in Badd located close to the river Aras. The leader of the other Khurramite movement was Abu Imran, who often clashed with Javidhans forces. During one of the clashes, in probably 816, Abu Imran was defeated and killed, whilst Javidhan was mortally wounded, dying three days later. Javidhan was succeeded by his apprentice Babak Khorramdin, who also married Javidhan's widow.[49]

Tabari records that Babak started his revolt in 816–817. At first, Al-Ma'mun paid little attention to Babak's uprising because of the difficulty of intervening from distant Khorasan, the appointment of his successor, and the actions of al-Fadl ibn Sahl. Such conditions paved the way for Babak and his supporters. Caliph Al-Ma'mun sent general Yahya ibn Mu'adh fought against Babak in 819–820, but could not defeat him several times. Two years later Babak overcome the forces of Isa ibn Muhammad ibn Abi Khalid. In 824–825 the Caliphate generals Ahmad ibn al Junayd and Zorayq b. ʿAlī b. Ṣadaqa were sent for subdue Babakʿs revolt. Babak defeated them and captured Jonayd. In 827–828 Moḥammad b. Ḥomayd was sent to overcome Babak. Though his several victories, in the last battle at Hashtadsar in 829, his troops were defeated by Babak. Caliph Al-Ma'mun's moves against Babak had failed when he died in 833. Babak's victories over Arab generals were associated with his possession of Badd fort and inaccessible mountain stronghold according to the Arab historians who mentioned that his influence also extended to the territories of today's Azerbaijan - “southward to near Ardabil and Marand, eastward to the Caspian Sea and the Shamakhi district and Shervan, northward to the Muqan (Moḡan) steppe and the Aras river bank, westward to the districts of Jolfa, Nakjavan, and Marand”.[50][49][46][42][51]

In 833, a great number of men from Jebal, Hamadan and Isfahan joined the Khorrami movement and settled near Hamadan. The new caliph al-Mutasim sent troops under Esḥāq b. Ebrāhīm b. Moṣʿab. The Khorramis were defeated in the battle near Hamadan. According to Tabari and Ibn al-'Asir, 60,000 khurramites were killed.[49]

In 835, al-Mutasim sent Khaydhar ibn Kawus al-Afshin a senior general and a son of the vassal prince of Osrushana to defeat Babak. Al-Mutasim set unusually large fees and expense allowances for Afshin. According to Saeed Nafisi, Afshin managed to attract Babak's spies on his side by paying much more money than Babak. When Afshin knew that Babak was aware of Bugha al-Kabir had been sent with a large amount of money for Afshin and preparing for an attack against Bugha, he used this information to drag Babak's full engagement where he succeeded to have Babak's comrades killed and Babak himself got away to Badd.[49][52][53][47]

Before Afshin's departure, caliph sent a group under Abu Said Moḥammad to reconstruct the forts demolished by Babak between Zanjan and Ardabil. Khurramites under Muawiyah attacked the Arabs but they were able to overcome the Khurramites which was recorded by Tabari as Babak's first defeat.[49]

The last battle between the Arab caliphate and the Khurramites took place in the fortress of Badd on 837. The Khurramites were defeated and Afshin reached the Badd. After capturing the Badd fortress, Babak came near the Araz River. His goal was to unite with the Byzantine emperor, gather new forces and continue the struggle. Thus, it was announced that the caliph Al-Mu'tasim would give a reward of 2 million dirhams to the person who handed him over alive. Babak's former ally, Sahl ibn Sumbat, handed Babak over to the Abbasid Caliphate, and on March 14, 838, Babak was executed in the city of Samarra.[49][54][46][47][55]

The Khurramites movement has intensified anti-Arab protests in many cities of Azerbaijan. During the weakening of the Arab caliphate, independent states began to emerge in the territory of Azerbaijan.[6][5][8]

Management policy

Under the Rashiduns and early Umayyads, the administrative system of the late Sassanid period was largely retained, each quarter of the state was divided into provinces, the provinces into districts, and the districts into sub-districts. Then caliphate created the Emirate system to manage large areas. During the Abbasid period, the number of emirates increased. In their turn, emirates were divided into mahals and mantagas. The person who ruled the emirate was called emir and appointed by the Caliph. The territories of Azerbaijan was first included in the fourth emirate, then in the third one.[56]

The Caliphate army initially had only Muslims as regular soldiers. While the other territories were conquested under the Caliphate, non-Arab local people who converted to Islam were allowed to join the army. Eventually non-Muslims who were called Dhimmis also allowed to join the army with being exacted from paying jizya. In addition, the Arabs relocated tens of thousands of Arab families from Basra, Kufa, Syria and Arabia to Azerbaijan in order to create a more reliable social base for themselves and to Arabize the population.[57][42][58]

Taxes under the Arabs coquest in the territories of Azerbaijan were divided into jizya, kharaj, khums. Jizya was levied in the form of financial charge on permanent non-Muslim subjects (dhimmis): kharaj was a tax on agricultural land and its produce. Sometimes a dhimmi was exempted from jizya if he rendered some valuable services to the state. Khums was taken as a fifth of movable property and fertile lands. Muslim population also paid Zakat as a form of alms-giving treated in Islam as a religious obligation or tax. Zakat (charity tax) was levied on livestock, plant and fruit products, gold and silver, and handicrafts. Zakat was spent on the needs of the clergy, orphans and the disabled. Absheron oil sources and salt lakes were also taxed.[59][60][61][62][63][64]

Economic life

The previously slow-growing rice industry began to grow rapidly and began to play a more important role in the economic life of Azerbaijan. In the 9th and 10th centuries, rice cultivation was widespread in Shabran, Shirvan, Sheki and Lankaran regions. Cultivation of flax and cotton were common in Azerbaijan at that time. Artificial irrigation of Mughan, Mil and other plains created special conditions for the increasing of cotton growing.[8][5]

The development of trade created conditions for the rapid development of camel breeding. In the Middle Ages, dromedary and two-humped camels were used in Azerbaijan. Due to their characteristics, camels were also widespread in the mountainous regions of Azerbaijan, where the semi-nomadic form of livestock predominated.[5][8]

Cities

In the ninth century, weaving became a highly developed field in Azerbaijani cities. Al-Istakhri and Hudud al-Alam (10th century) stated that there was no city equal to Barda, which planted many trees and produced much silk. Among the other regions of Arran, silkworm breeding also developed in Shabran and Shirvan.[8][6]

At that time, Barda, known as the "Mother of Arran" and the residence of the caliph's rulers, was the largest place not only in Azerbaijan, but in the whole Caucasus. Barda's “Kurki” bazaar” was one of the most popular bazaars in the Middle East.[35][8]

Gandja was one of the biggest cities of Azerbaijan during Caliphate authority. According to the Azerbaijani historian Ismayil bey Zerdabli, Gandja was an “essential city”, “possessed fortification, great cattle with high walls” and it was “the last forepast of Muslim world in frontiers”.[65][6][8]

Local artisans made clothes, carpets, wooden utensils made of Khalandj (iron tree) for the interior and foreign markets of Nakhchivan.[5][6]

The cities of Shirvan and Shamakhi were famous for their silk products. Silk and silk clothes were exported to other cities in the Caucasus and the Middle East.[66][8][6]

Feudal states in IX-XI centuries

As a result of the weakening of military-political power of the Arab caliphate, as well as the growing tendency to disobey the central government, some provinces became independent and seceded from the Caliphate in the 9-10th centuries. Feudal states such as Shirvanshahs, Shaddadids, Sallarids and Sajids emerged in the territory of Azerbaijan.[67][68][69][70]

Shirvanshahs

The Shirvanshah dynasty was an Islamic dynasty that ruled Shirvan from 861 to 1538 and eventually covered the shores of the Caspian Sea from Derbent to the Kura River.[67][71]

According to Ibn Khordadbeh, the title of “Shirvanshah” referred to the local rulers of Servan (Shirvan) who received their title from the first Sassanid emperor, Ardashir.[72]

From the late 8th century, Shirvan was under the rule of the members of the Arab family of Yazid ibn Mazyad al-Shaybani (d. 801), who was named governor of the region by the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid.[67][70] His descendants, the Yazidids, would rule Shirvan as independent princes until the 14th century.[67] By origin, the Yazidids were Arabs of the Shayban tribe and belonged to high ranking generals and governors of the Abbasid army.[70] In the turmoil surrounding the Abbasid Caliphate after the death of the Caliph al-Mutawakkil in 861, the grandson of Yazid b. Mazyad Shaybani, Haytham ibn Khalid, declared himself independent and accepted the ancient title of Shirvanshah. The dynasty continuously ruled the area of Shirvan either as an independent state or a vassal state until the Safavid times.[72]

V.F Minorsky in his book titled "A History of Sharvan and Darband in the 10th–11th Centuries" distinguishes four dynasties of Shirvanshahs; l. The Shirvanshahs, (the Sassanids designated them for the protection of northern frontier; 2. Mazyadids, 3.Kasranids; 4.Derbent Shirvanshahs or Derbent dynasty.[70][73]

According to al-Masudi, in 917, Russian merchants attacked the Caspian provinces and Shirvan from the Don River with 500 ships. However, due to the lack of a fleet of Shirvan ruler Ali ibn Haysam, Russian merchants looted the area, as a result, the ruler of Shirvan was dethroned.[69][74]

According to the anonymous work Hudud al-Alam, the Shirvanshahs united the Layzan in 917. Then Shirvanshah Abu Tahir (917-948) restored Shamakhi (Yazidiyya) in 918 and moved the capital to this city.[69][74]

During the reign of Ahmad ibn Muhammad, the Shirvanshah state was dependent on the Sallarid dynasty for some time and became independent again after the collapse of the Sallarids.

After Ahmad's death, his son Muhammad ruled for ten years (981-991). In the first years, Mohammad was able to include the city of Gabala in his state. In 983, he rebuilt the castle walls of Shabran, then captured Barda, and appointed Musa as its governor. Khurasan, Tabasaran, Sheki and were also annexed to Shirvanshahs.[69]

At the end of the 10th - beginning of the 11th century they began wars with Derbent (this rivalry lasted for centuries), and in the 1030's they had to repel the raids of the Rus, and Alans.[75]

The last ruler of the Mazyadid was Yazid ibn Ahmad, and from 1027 to 1382, the Kasranids dynasty began to rule the Shirvanshahs. In 1032 and 1033, the alans attacked the territory of Shamakhi, but were defeated by the troops of the Shirvanshahs.[69] The Kasranid dynasty ruled the state independently until 1066 when the Seljuk tribes came to the territory of Azerbaijan, Shirvanshah I Fariburz accepted dependence on them, preserving internal independence.[71][72][70]

In the 1080's, however, Fariburz, taking advantage of the weakening of his neighbors, who were also subjected to the Seljuk invasion, extended his power to Arran and appointed a governor in Ganja.[75]

Sajid dynasty

The Sajid dynasty was an Islamic dynasty that ruled from 889–890 until 929. The Sajids ruled Azerbaijan first from Maragha and Barda and then from Ardabil.[76]

Muhammad ibn Abi'l-SajDiwdad the son of Diwdad, the first Sajid ruler of Azerbaijan, was appointed as its ruler in 889 or 890. Muhammad's father Abu'l-SajDevdad had fought under the Ushrusanan prince AfshinKhaydar during the latter's final campaign against the rebel BabakKhorramdin in Azerbaijan, and later served the caliphs. For the services rendered to the state, the Sajids were granted one of the largest and richest provinces of the Caliphate - Azerbaijan.[77] Toward the end of the 9th century, as the central authority of the Abbasid Caliphate weakened, Muhammad was able to form a virtually independent state. At the end of the ninth century (898-900) coins were minted named after Muhammad ibn Abu Saj.Muhammad ibn Abu Saj succeeded in incorporating much of the South Caucasus into the Sajid state.The first capital of Sajids was Maragha though they usually resided in Barda.[78][79][76]

Yusuf ibn Abi'l-Saj came to power in 901 and demolished the walls of Maragha and moved the capital to Ardabil. The eastern borders of the Sajid dynasty extended to the shores of the Caspian Sea, and the western borders to the cities of Ani and Dabil (Dvin). Yusuf ibn Abi'l-Saj relations with the caliph were not good. In 908, a caliphate army was sent against Yusuf, but al-Muqtafi died and his successor, al-Muqtadir, moved a large army against Yusuf ibn Abi'l-Saj and forced him to pay a tribute of 120 thousand dinars a year. Yusuf ibn Abi'l-Saj made peace with Sajid. Abu'l-Hasan Ali ibn al-Furat the vizier of al-Muqtadir, played a key role in establishing peace, and since then Yusuf ibn Abi'l-Saj has considered him his patron in Baghdad and often mentioned him on his coins. Peace allowed Yusuf ibn Abi'l-Saj invested with the governorship in Azerbaijan by the caliph in 909.[80][81][82]

After the dismissal (in 912) of his protector in Baghdad, vizier ibn al-Furat, Yusuf ibn Abi'l-Saj stopped annual tax payments to the caliphate's treasury.[83][84]

According to the Azerbaijani historian Abbasgulu aga Bakikhanov, from 908-909 to 919, the Sajids made the Shirvanshah Mazyadids dependent on them. Thus, in the beginning of the X century the Sajid state included territories from Zanjan in the south to Derbent in the north, the Caspian Sea in the east, to the cities of Ani and Dabil in the west, covering most of the lands of modern Azerbaijan.[83]

During the reign of Yusuf ibn Abu Saj, Russian merchants attacked the Sajid territory from the north through the Volga in 913-914. Yusuf ibn Abu Saj repaired the Derbent wall to strengthen the northern borders of the state. He also rebuilt the collapsed part of the wall inside the sea.[85]

In 914, Yusuf Ibn Abu-Saj organized a campaign towards Georgia. Tbilisi was chosen as the center of military operations. He first occupied Kakheti and captured the fortresses of Ujarma and Bochorma, and returned after capturing several territories.[84][86]

After the death of Yusuf ibn Abu Saj, the last ruler of the Sajid dynasty Deysam ibn Ibrahim was defeated by the ruler of Daylam (Gilan) Marzban ibn Muhammad who ended the Sajid dynasty and founded the Sallarid dynasty in 941 with its capital in Ardabil.[86][84]

Sallarid dynasty

The Sallarid dynasty was an Islamic dynasty that ruled the territories of Azerbaijan, as well as Iranian Azerbaijan from 941 until 979.[87][84]

Marzuban ibn Muhammad, ended the existence of the Sajid dynasty and founded the Sallarid dynasty in 941, was the son of the founder of the Musafirid dynasty, Muhammad ibn Musafir , who ruled in Daylam. In 941, Marzuban, together with his brother Vahsudan, overthrew their father. In the same year, Marzuban set out to conquer Azerbaijan. He captured Ardabil and Tabriz, then extended his power to Barda, Derbent and also to North-Western regions of Azerbaijan. Shirvanshahs agreed become Marzuban's vassal and pay tribute. [88][84]

In 943-944, the Russians organized another campaign to the Caspian region, which was many times more brutal than the 913/14 March. As a result of this campaign, which affected the economic situation in the region, Barda lost its position and essence as a large city and gave this position to Ganja.[89][90][91]

The Sallarid army was defeated several times. The Rus captured Barda, the capital of Arran. The Rus' allowed the local people to retain their religion in exchange for recognition of their overlordship; it is possible that the Rus' intended to settle permanently. According to ibn Miskawaih, the local people broke the peace by stone-throwing and other abuse directed against the Rus', who then demanded that the inhabitants evacuate the city. This ultimatum was rejected, and the Rus' began killing people and holding many for ransom. The slaughter was briefly interrupted for negotiations, which soon broke down. The Rus' stayed in Bardha'a for several months, using it as a base for plundering the adjacent areas, and amassed substantial spoils.[84]

The city was saved only by an outbreak of dysentery among the Rus'. Marzuban then laid siege to Barda, but received news that the Hamdanid amir of Mosul, Marzuban left a small force to keep the Rus in check, and in a winter campaign (945-946), defeated al-Husain. The Rus meanwhile decided to leave, taking as much loot and prisoners as they could.[84]

In 948, Marzuban was defeated by Hamadan and the ruler of Isfahan, Rukn ed-Daula, and was taken prisoner at Samiram Castle. After that, the territory of Sallarids became the place of a ruthless struggle for power between Marzuban's brother Vahsudan, his sons and Deysam Sajid. This momentary weakness in the central administration allowed the Rawadids and Shaddadids to take control of the areas to the northeast of Tabriz and Dvin, respectively.[84]

After Marzuban’s death, Ibrahim, the youngest son of him, was appointed ruler of Dvin (957–979) and later Azerbaijan (962–966 and 966–979) by the caliph. According to Wilferd Madelung, in 968 Sallaryd İbrahim al Marzuban reaffirmed Sallarids authority over Shirvan and al-Bab (Darband). The Sallaryid dynasty was forced to recognize the rule of the Shaddadids, which strengthened in Ganja in 971. Then, they was assimilated by the Seljuk Turks at the end of the 11th century.[92][84]

Shaddadids

The Shaddadids were a Muslim dynasty that ruled the area between the rivers Kura and Araxes from 951 to 1199 AD.[93]

Muhammad ibn Shaddad was considered the founder of the Shaddadid dynasty.Taking advantage of the weakening of Sallarids, Muhammad ibn Shaddad took control over the city of Dvin and established his state.The Shaddadids eventually extended their power over the territories of Azerbaijan and ruled major cities such as Barda and Ganja.[93]

According to Minorsky, Laskari ibn Muhammad and his brother Fadl ibn Muhammad fortified in Ganja in 969 or 970 during the war with the Sallaryd dynasty, then captured Shamkir and Barda and began to rule in Azerbaijan.Lashkari I ended Musafirid influence in Arran by taking Ganja in 971.[93]

Laskari ruled in Ganja for eight years, thenFadl ibn Muhammad established himself as emir of Arran from 985 to 1031.Al-Fadhl was the first Shaddadid emir to issue coinage, locating his mint first at Partav (Barda'a), and was later transferred to Ganja. He expanded Shaddadids’ realm in Arran, capturing Baylagan in 993.[93]

Fadl ibn Muhammad built the Khodaafarin Bridges along the Aras River to reconnect the territories between the north and south banks of Aras. In 1030, he organized an expedition against the Khazar khaganate.[94]

In 1030, a new attack on Shirvanshahs by 38 Russian ships took place, Shirvanshah Manučehr was heavily defeated. At that time, Fadl I's son Askuya rebelled in Beylagan. Fadl I's loyal son Musa paid money to the Russians to save Beylagan. As a result, Askuya's revolt was suppressed, and he was executed.[93]

According to Minorsky, the period of AbulaswarShavur, who came to power after several changes in the throne, was called the zenith period of the Shaddadids. He was the last independent ruling Shaddadid emir. The Ziyarid prince Kaykāvus b. Eskandar mentioned Abu’l-Aswār as “a great king” in his Qābus-nāma written when he lived for several years in Ganja fighting against the Byzantines.During Shavur’s reign, the Shaddadids recognized the rule of the Seljuk sultan Togrul, prevented the attacks of the Alans from the north in 1063-1064, and maintained an allied relationship with thepeople of Tbilisi.[93]

After Abulaswar Shavur died in Ganja in 1067, the rule of Shaddadids in Ganja also came to an end. The person who continued the rule of the Shaddadids in Arran was Fadl III, who ascended the throne in Ganja in 1073. In 1075 Alp Arslan annexed the last of the Shaddadid territories. According to the anonymous Tariḵ Bab al-abwab, Alp Arslan appointed al-Bab and Arran as iqta to his slave Sav Tegin who seized these areas by force from Fażlun in 1075 and ended the dynasty’s reign.A branch of the Shaddadids continued to rule in the Ani emirate as vassals of the Seljuq Empire, while the others were assimilated by the Seljuqs.[95][92]

See also

References

- Verda, Matteo (2014). Azerbaijan: An introduction to the Country. Edizioni Epoké. ISBN 9788898014361.

- O. Olson, James; Brigance Pappas, Lee; C. J. Pappas, Nicholas (1994). An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 27. ISBN 9780313274978.

- "SASANIAN DYNASTY – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- Abū Jaʿfar Muḥammad, Al-Ṭabarī (1999). The History of al-Ṭabarī (PDF). 5. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0791443566.

- ISMAILOV, DILGAM (2017). HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN (PDF). Baku: Nəşriyyat – Poliqrafiya Mərkəzi.

- Azərbaycan tarixi. Yeddi cilddə. II cild (III-XIII əsrin I rübü. Bakı: Elm. 2007. ISBN 978-9952-448-34-4.

- "ALBANIA – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- Zardabli, Ismail bey (2014). THE HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN: from ancient times to the present day. Lulu.com. p. 61. ISBN 9781291971316.

- Farrokh, Kaveh; SÁNCHEZ-GRACIA, Javier; MAKSYMIUK, Katarzyna (2019). "Caucasian Albanian warriors in the armies of pre-Islamic Iran". Historia i Świat. Siedlce. 8: 21–46. doi:10.34739/his.2019.08.02. ISSN 2299-2464 – via Academia.edu.

- A. West, Barbara (2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 148. ISBN 9781438119137.

- "Ancient Iran - The Sāsānian period". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- Recueil Des Cours. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. 1968. p. 205. ISBN 9789028615021.

- Yarshater, Ehsan, ed. (1983). The Cambridge History of Iran. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 141. ISBN 9780521200929.

- Vladimir, Minorsky (1958). A History of Sharvan and Darband in the 10th-11th Centuries. Cambridge.

- "Бакинско-Азербайджанская епархия РПЦ | VII. Последующая судьба Албанской Церкви". baku.eparhia.ru. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- Marcellinus, Ammianus (1939). ROLFE, J.C. (ed.). The later Roman Empire. Cambridge.

- Hughes, Ian (2013). Imperial Brothers: Valentinian, Valens and the Disaster at Adrianople. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781473828636.

- Dasxuranci, Movses (1961). The History of the Caucasian Albanians By Movses Dasxuranci. Translated by Dowsett, C. J. F. Oxford University Press.

- "CTESIPHON – Encyclopaedia Iranica". web.archive.org. 2016-05-17. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- Brummell, Paul (2005). Turkmenistan. Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 9781841621449.

- "ḴOSROW II – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008). Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781845116453.

- Dasxuranci, Movses (1961). The History of the Caucasian Albanians. Oxford University Press.

- "Бакинско-Азербайджанская епархия РПЦ | Святой Елисей". baku.eparhia.ru. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- Wood, Philip (2013). The Chronicle of Seert: Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq. Oxford University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0199670673.

- "ARRĀN – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- "Бакинско-Азербайджанская епархия РПЦ | VIII. Архитектурное наследие Албанской Церкви". baku.eparhia.ru. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- Liberman, Sherri (2003). A Historical Atlas of Azerbaijan. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 9780823944972.

- "Internet History Sourcebooks Project". sourcebooks.fordham.edu. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- "DASTGERD – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- M. Diakonoff, Igor (1999). The Paths of History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521643986.

- Мамедова, Фарида (2005). Кавказская Албания и албаны. Azərnəşr. ISBN 9789952807301.

- History of al-Tabari. The Conquest of Iran A.D. 641-643. 14. Translated by G., Rex Smith. SUNY Press. 2005. ISBN 9781438420394.

- "BAYLAQĀN – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- "BARḎAʿA – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- "NAḴJAVĀN – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- Alan Brook, Kevin (2006). The Jews of Khazaria. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 126. ISBN 9781442203020.

- Yahya Blankinship, Khalid (1994). The End of the Jihad State: The Reign of Hisham Ibn 'Abd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. SUNY Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780791418277.

- Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi. 4. Peter de Ridder Press. 1975.

- D.M., Dunlop (1954). The History of the Jewish Khazars. Princeton University Press.

- Dunlop, D. M. (2012-04-24). "al-D̲j̲arrāḥ b. ʿAbd Allāh". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition.

- "AZERBAIJAN iv. Islamic History to 1941 – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- Hawting, G. R (2002). The First Dynasty of Islam: The Umayyad Caliphate AD 661-750. Routledge. ISBN 9781134550586.

- L. Esposito, John (2000). The Oxford History of Islam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199880416.

- "ШАМХОР - это... Что такое ШАМХОР?". Словари и энциклопедии на Академике (in Russian). Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- "ḴORRAMIS – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- Crone, Patricia (2012). The Nativist Prophets of Early Islamic Iran: Rural Revolt and Local Zoroastrianism. Cambridge University Press. p. 46. ISBN 9781139510769.

- Spuler, Bertold (1968). The Muslim World: The age of the Caliphs. E. J. Brill.

- "BĀBAK ḴORRAMI – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- Nafīsī, S. (1963). Bābak-e Ḵorramdīn. Tehran.

- ʻUmar, Fārūq, ed. (2001). دراسات في تاريخ الفرق في العصر الإسلامي الوسيط. Al al-Bayt University.

- Bahramian, Ali; Hirtenstein, Stephen; Gholami, Rahim (2013-12-04). "Bābak Khurram-Dīn". Encyclopaedia Islamica.

- K̲h̲ān Najībābādī, Akbar Shāh (2001). Mubārakfūrī, Ṣafī al-Raḥmān (ed.). History of Islam. Darussalam. pp. 445–451. ISBN 9789960892887.

- Signes Codoñer, Juan (2016). The Emperor Theophilos and the East, 829–842: Court and Frontier in Byzantium during the Last Phase of Iconoclasm. Routledge. p. 250. ISBN 9781317034278.

- Kaldellis, Anthony (2019). Romanland: Ethnicity and Empire in Byzantium. Harvard University Press. p. 127. ISBN 9780674986510.

- Joseph Saunders, John (1978). A History of Medieval Islam. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415059145.

- "Abbasid caliphate | Achievements, Capital, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- "Umayyad dynasty | Achievements, Capital, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- "Kharāj | Islamic tax". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- "jizyah | Definition & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- "JEZYA – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- Shah, Nasim Hasan (1988). "The concept of Al‐Dhimmah and the rights and duties of Dhimmis in an Islamic state". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 9 (2): 217–222. doi:10.1080/02666958808716075. ISSN 0266-6952.

- Bowering, Gerhard, ed. (2013). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton University Press.

- Visser, Hans (2009). Islamic Finance: Principles and Practice. Edward Elgar Pub. ISBN 978-1845425258.

- "GANJA – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- "ŠERVĀN – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- "ŠERVĀNŠAHS – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- Aşurbəyli, Sara (2006). Şirvanşahlar dövləti. Əbilov, Zeynalov və oğulları. ISBN 5-87459-229-6.

- ŞƏRİFLİ, M.X (2013). IX ƏSRİN İKİNCİ YARISI – XI ƏSRLƏRDƏ AZƏRBAYCAN FEODAL DÖVLƏTLƏRİ (PDF). AZƏRBAYCAN MİLLİ ELMLƏR AKADEMİYASI TARİX İNSTİTUTU.

- Vladimir Minorsky. A History of Sharvan and Darband in the 10th-11th Centuries.

- "ŠERVĀN – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- Barthold, W.; Bosworth, C. E. (2012-04-24). "S̲h̲īrwān S̲h̲āh". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition.

- Жузе, П.К. (1937). Мутагаллибы в Закавказьи в IX-X вв. (К истории феодализма в Закавказьи). p. 179.

- Abū al-Ḥasan, Masudi (2015). MEADOWS OF GOLD. TAYLOR & FRANCIS.

- Ryzhov, K.V (2004). All the monarchs of the world. The Muslim East. VII-XV centuries. Veche.

- "AZERBAIJAN iv. Islamic History to 1941".

- Стэнли, Лэн-Пуль (2004). Мусульманские династии. Хронологические и генеалогические таблицы с историческими введениями. pp. 92–93.

- Bayne Fisher, William, ed. (1975). The Cambridge History of Iran, Том 4. ISBN 9780521200936.

- Minorskiy, Vladimir (1957). Studies in Caucasian history. Cambridge University Press. p. 111.

- Muir, William (2004). The Caliphate: Its Rise, Decline and Fall from Original Sources. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 1417948892.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Madelung, W (1975). The Minor Dynasties of Northern Iran. Cambridge University Press. pp. 198–249. ISBN 0-521-20093-8.

- Aliyarli, Suleyman (2009). History of Azerbaijan. Chirag. p. 209.

- Yarshater, Ehsan, ed. (1983). The Cambridge History of Iran. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 141. ISBN 9780521200929.

- Василий Владимирович, Бартольд (1924). Место Прикаспийских областей в истории мусульманского мира. Баку.

- ISMAILOV, DILGAM (2017). HISTORY OF AZERBAIJAN (PDF). Baku: Nəşriyyat – Poliqrafiya Mərkəzi.

- Clifford Edmund, Bosworth (1996). The New Islamic Dynasties. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231107143.

- Ryzhov, K.V (2004). All the monarchs of the world. Muslim East VII-XV centuries. Veche. ISBN 5-94538-301-5.

- "BARḎAʿA – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-12-28.

- "AZERBAIJAN iv. Islamic History to 1941 – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-08-31.

- Abu '. Ibn Miskawaih, Ahmad Ibn Muhammad (2014). The Tajarib Al-Umam; Or, History of Ibn Miskawayh. Nabu Press. ISBN 978-1295768103.

- Vladimir Minorsky. Studies in Caucasian History.

- "SHADDADIDS – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-12-28.

- "ARAXES RIVER – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-12-28.

- "SHADDADIDS – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-12-28.