Shaki, Azerbaijan

Shaki (Azerbaijani: Şəki; until 1968 Nukha, Azerbaijani: Nuxa) is a city in northwestern Azerbaijan, surrounding the district of the same name.

Shaki

Şəki | |

|---|---|

City Subordinate to the Republic | |

| |

Seal | |

Shaki Location of Shaki in Azerbaijan | |

| Coordinates: 41°11′31″N 47°10′14″E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Sheki-Zagatala |

| Government | |

| • Head of the Executive Power | Elkhan Usubov |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9 km2 (3 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 700 m (2,300 ft) |

| Population (2017)[2] | |

| • Total | 68,360 |

| • Density | 7,600/km2 (20,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (AZT) |

| Postcode | AZ5500 |

| Area code(s) | +994 02424 |

| Website | sheki-ih |

Shaki is in northern Azerbaijan on the southern part of the Greater Caucasus mountain range, 240 km (150 mi) from Baku. The population is 63,000.

Etymology

According to the Azerbaijani historians, the name of the town goes back to the ethnonym of the Sakas, who reached the territory of modern-day Azerbaijan in the 7th century BC and populated it for several centuries.[3] In the medieval sources, the name of the town is found in various forms such as Sheke, Sheki, Shaka, Shakki, Shakne, Shaken, Shakkan, Shekin.[4]

History

Shaki was founded in the 8th century BC.[5] It was one of the biggest cities of the Albanian states in the 1st century. The main temple of the ancient Albanians was located there. The kingdom of Shaki was divided into 11 administrative provinces. Shaki was one of the important political and economic cities before the Arab invasion. But as a result of the invasion, Shaki was annexed to the third emirate. An independent Georgia principality, Hereti, was established in times when the Arab caliphate was weak.[4] The city was also ruled by the Atabegs of Azerbaijan and the Khwarazmian Empire.

Antiquity

There are traces of large-scale settlements in Shaki dating back to more than 2700 years ago. The Sakas were an Iranian people that wandered from the north side of the Black Sea through Derbend passage and to the South Caucasus and from there to Asia Minor in the 7th century B.C. They occupied a good deal of the fertile lands in South Caucasus in an area called Sakasena. The city of Shaki was one of the areas occupied by the Sakas. The original settlement dates back to the late Bronze Age.

Shaki was one of the biggest cities of the Albanian states in the 1st century. The main temple of the ancient Albanians was located there. The kingdom of Shaki was divided into 11 administrative provinces.

As a result of archaeological excavations conducted in 1902 in the village of Boyuk-Dakhna in the Shaki region, various ceramic products and a stone tombstone dating back to the II century AD and containing inscriptions in Greek were discovered.[6]

Shaki was one of the important political and economic cities before the Arab invasion.[7] But as a result of the invasion in 654, Shaki was annexed to the third emirate. An independent Georgia principality, Hereti, was established in times when the Arab caliphate was weak.[8] In 1117, the region was captured by the army of the Georgian king David IV[9]

The city was also ruled by the Atabegs of Azerbaijan and the Khwarazmian Empire, before the Mongol invasion.

Feudal era

Around the turn of the 9th century Šakē formed with Kʿambēčan (to the west) [10] In the XIII-XIV centuries, the territory of the present Shaki district was a part of the state of Shirvanshahs. Management of Shaki was entrusted to the son of Rashid al-Din Hamadani – Jalat[11] In the 30s of the XIV century, the local Oirat tribe took power.[12] After the collapse of the Hulagu Khan's rule in the first half of the 14th century, Shaki gained independence under the rule of Sidi Ahmed Orlat.[13] In 1392, Emir Timur captured Shaki, and the ruler of Shaki, Seyid Ali, was killed. Seyid Ali's son, Seyid Ahmed, who came to power, along with Shirvanshah Ibrahim I Derbendi, accompanied Timur on his third campaign against Azerbaijan in 1399.[14][15]

In the early 1500s, Safavid king Ismail I (r. 1501–1524) conquered the area, but the town continued to be governed by its hereditary rulers, under Safavid suzerainty.[16] Ismail's son and successor Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524–1576) put an end to this, and in 1551, he appointed the first Qizilbash governor to rule the town.[16] The territory was annexed to the Safavid dynasty as the independent Sheki beylerbey reigned by Toygun-bey Qajar.[17][18]

Safavid rule was twice briefly interrupted by the Ottomans between 1578 and 1603 and 1724–1735.

In 1734-1735, there was a revolt of poor people against the policy of Nadir Shah in the village of Bilecik (Shaki)[4]

In 1741, there was another uprising against the local ruler, Melik Najaf. Appointed by Nadir Shah, Haji Chelebi announced the formation of an independent Sheki khanate in 1743. Upon learning of this, Nadir Shah Afshar sent his army to Shaki. Haji Chelebi took refuge in the fortress of Gelesen-Geresen. In 1746, Haji Celebi was forced to recognize the authority of Nadir Shah. However, new uprisings and the death of Nadir Shah allowed Haji Chelebi to re-declare himself Khan[5][19] During the existence of Shaki khanate, the local population of the city was engaged in silkworm breeding, craft and trade.[8] As a result of a flood in the river Kish, the city of Shaki was partially ruined and the population was resettled in the present day city.[20]

In alliance with the Shamakhi Khan, in 1748 Haji Chelebi attempted to besiege the Bayat fortress. The defeat in the battle of Bayat, which lasted for a month, had been a serious setback for allies.[21]

The Jaro-Balakan Jamaat, Qabala and Ares sultanates were dependent on the Shaki khanate[22]

In 1751, Haji Chelebi defeated the army of the Kakheti king Heraclius II. At the initiative of Heraclius II, a political conspiracy of the Kakheti Kingdom, the Karabakh, Ganja, Irevan, Nakhichevan, and Karadag khanates against the Shaki khan was arranged. In 1752, in the area of Kyzylgaya, Georgian troops unexpectedly attacked the khans: they were captured. Haji Celebi himself defeated the Georgians in the battle near Ganja and came to the aid of the khans. The army of Shaki khan captured Gazakh and Borchali.[23]

In 1767, the Western part of the Shamakhi khanate was annexed to the Shaki khanate.[22]

In 1785, the Shaki khanate became dependent on the Guba khanate. However, this did not last long: after the death of Fatali khan of Guba, the Shaki khanate regained its independence.[24][25]

During the reign of Selim khan, the territory of the khanate was conditionally divided into 8 magals, which were ruled by naibs directly appointed by the khan himself.[23]

On May 21, 1805, the treaty of Kyurekchay was signed between Russia and the Shaki khanate, the main condition of which was the annexation of the Shaki khanate to Russia. In 1806, the Russian army moved to Shaki. Selim khan was removed from positions of power. A temporary Board of Pro-Russian beks was created.[26]

Modern era

The area was fully annexed by Russia by the Treaty of Gulistan in 1813 and the khanate was abolished in 1819 and the Shaki province was established in its place.[27][28] Shaki province was merged with provinces of Shemakha, Baku, Susha, Lankaran, Derbent and Kuban in 1840 and Caspian Oblast was created. At the same time Shaki was renamed as Nuha. The oblast was dissolved in 1846 and it was raion center of Shemakha Governorate. After the earthquake in Shemakha in 1859, the governorate was renamed as Baku Governorate. On 19 February 1868, raion of Nuha was passed to newly created Yelizavetpol Governorate with one of Susha. After founding of USSR, it was the center of Nuha raion. Its one was abolished on 4 January 1963 and was bounded to one of Vartashen. Nuha one was founded again in 1965 and finally, city and raion regained traditional name in 1968.

During its history, the town saw devastation many times and because of that, the oldest historic and architectural monuments currently preserved are dated to only the 16th–19th centuries. For many centuries, Shaki has been famous for being the center of silkworm-breeding. Originally located on the left bank of the river Kish, the town sat lower down the hill, however Shaki was moved to its present location after a devastating flood in 1772 and became the capital of Shaki Khanate. As the new location was near the village of Nukha, the city also became known as Nukha, until 1968 when it reverted to the name Shaki.[29][30]

In 1829, the Khanabad factory was opened in Shaki. The products of the Nukha silk-winding factory, which opened in 1861, were awarded a medal in London in 1862.[31] The Shaki uprising of 1838 had an impact on the administrative, judicial, and agrarian reforms of the 1840s.

In 1917, Soviets of Workers' deputies were formed in a number of cities of Azerbaijan, including Shaki.[32]

In May 1920, Soviet power was established in Shaki, as well as in other cities of Azerbaijan.[31]

In 1930, an uprising against the policy of collectivization in the Azerbaijan SSR broke out in the village of Bash Goynyuk in the Shaki district. The Soviet regime was abolished. Soon, Red Army units moved into the city. The rebels were subject to execution.[33]

Republic era

A letter from the Chairman of the Kyoto City Council, Daisaku Kadokawa, on 8 December 2008, said that Sheki was a member of the World Historical Cities League. Sheki became a member after the meeting of the Board of the World Cities League in October 2008.

Works to be done in the field of renovation and construction in 2012 were identified: Together with Sheki City Executive Authority and Architectural Urbanization Committee, Shaki City General Plan was prepared. According to the General Plan, it was planned to implement a number of infrastructure projects, as well as the expansion of the city to the west, inclusion of city of Oxud, İncə, Shaki, Kish, and Qoxmuq villages to Shaki.[34]

Geography

Shaki is surrounded by snowy peaks of the Greater Caucasus, which in some places reaches 3000–3600 m. Shaki's climate includes a range of cyclones and anticyclones, air masses and local winds. The average annual temperature in Shaki is 12 °C. In June and August, the average temperature varies between 20 and 25 °C.

The mountain forests around the area prevent the city from floods and overheating of the area during summer. The main rivers of the city are the Kish and Gurjhana. During the Soviet rule of Azerbaijan, many ascended to Shaki to bathe in its prestigious mineral springs.

Demographics

The number of Shaki population is 174.1 thousand people. Including, the rural population is 105.7 thousand people, while the urban population is 66.9 thousand people. Population density is 72 people per 1 square kilometer. Of the total population, 86.4 thousand or 49.6% of men, 87.7 thousand or 50.4% are women. 38.4 percent of the population lives in the city and 61.6 percent lives in the village.[35]

Religion

A home to ancient Caucasian Albanian churches, religion is highly important to the people of Shaki due to its historical religious diversity. There are many churches and mosques in the city. Some churches such as the Church of Kish in the vicinity of Shaki are thought to be approximately 1,500 years old.[36] The Khan's Mosque, Omar Efendi Mosque and Gileili Minaret are considered important places of worship in the city.[37]

Economy

During 1850–70, Shaki became international silk production centre.[38] More than 200 European companies opened offices in the city, while silkworms to the tune of 3 million roubles were sold to them in a year.[38]

Shaki possesses a small silk industry and relies on its agricultural sector, which produces tobacco, grapes, cattle, nuts, cereals and milk. The main production facilities of Shaki are the silk factory, gas-power plant, brick factory, wine factory, sausage factory, conserve factory, and a dairy plant with its integrated big scale Pedigree Dairy Farm.

Tourism and shopping

In 2010, Shaki was visited by 15,000 foreign tourists from all around the world.[39]

Culture

Shaki has one of the greatest density of cultural resources and monuments that include 2700 years of Azerbaijani history. The city boasts a lot of houses with red roofs. In pop culture, probably the most famous feature of Shakinians are their nice sense of humor and comic tales.[40] Shaki's comic tales hero Hacı dayı (Uncle Haji) is the subject of nearly all jokes in the area.[41][42]

Shaki has always played a central role in Azerbaijani art and more generally in the art and architecture of Azerbaijan. Under the name of Nukha, the city is the scene of much of the action in Brecht's play The Caucasian Chalk Circle.[43]

In the second half of the XIX century. Nukha was ranked second in terms of trade and industry development. New types of city and county schools were created.[44]

According to the Resolution of the Council of Ministers of the Azerbaijani SSR No. 97 of March 6, 1968, the "Yukhary Bash" area in Nukha was declared an architectural reserve.[45]

In 1975, the construction of the drama theater building was completed in Shaki.[46]

In 1983, the Shaki craft Museum opened.[9]

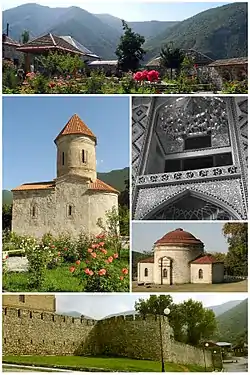

Architecture

Architecture in Shaki has largely been shaped by Shaki's history. It goes back to a time, when it was a market center on the Silk Road, linking Dagestan, Russia to the northern trade routes through the Caucasus.[47]

The city's central and main open city squares are dominated by two Soviet towers.[37] Many public places and private houses in Shaki are decorated with shebeke, a wooden lattice of pieces of coloured glass, held together without glue or a single nail.[48] The technique is complex and known only to a few artisans who pass their meticulous craft from generation to generation.[48]

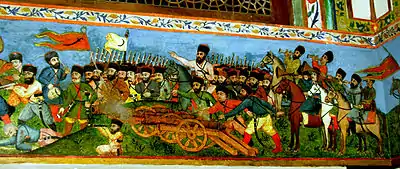

The Palace of Shaki Khans which was a summer residence of Shaki Khans, still remains one of the most visible landmarks of Shaki. Constructed in 1762 without a single nail is one of the most marvelous monuments of its epoch.[37] Displayed within the palace are Azerbaijani Khanate-era artifacts, as well as displays of the art scene, considered to be among the finest in the world.[49][50] Historic Centre of Sheki with the Khan's Palace was added to UNESCO's World Heritage List during the 43rd session of the World Heritage Committee held in July 2019.[51]

The Shaki Castle which was built by the founder of the Shaki Khanate Haji Chelebi Khan (1743–1755), near the village of Nukha on the southern foothills of the Caucasus. The fortress walls are close to a thousand and two hundred meters long and over two meters thick.[52] Protected by numerous bastions, the fortress is entered by two main gates from the north and south. At the height of the khanate, the fortress contained a gated palatial complex and public and commercial structures of the city, while the residential quarter was situated outside its walls. It was restored extensively between 1958 and 1963.[53] Many years Shaki fortress safeguarded approaches to the city, the acts of bravery by its defendants of fight with foreign oppressors had been written in many history books. In Leo Tolstoy's well-known Hadji Murat novel, Shaki fortress had selected as place of events.[40]

Sightseeing places

- The fortress (XVIII century);

- Shaki Khan's mosque (XVIII century);

- Upper caravanserai (XVIII century);

- Lower caravanserai (XVIII century);

- The house of Shaki khans (XVIII century);

- The minaret of the Gileyli mosque (XVIII century)

- Gedek mosque; (XIX century);

- Juma mosque (XIX century);

- Mosque of Omar Effendi (XIX century);

- Mosque "Kyshlak" (XIX century);

- Underground bath (XIX century);

- "Aguantar" bath (XIX century);

- "Kyshlak" bath (XIX century);

- The round temple (XIX century);

- The bridge on the Gurjanachai river (XVIII—XIX centuries);

- The remains of the Gelesan-Goresen fortress

- The house-museum of Mirza Fatali Akhundov;

- The house-museum of Rashid Bey Efendiyev;

- The house-Museum of Sabit Rahman.[54]

Cuisine

Perhaps the best-known aspect of Shaki cooking is its rich sweet dishes. Shaki is traditionally held as the home of special type of baklava, called Shaki Halva.[55] Others include nabat boiled sugar and sweet pesheveng.[40]

Shaki also has some famous dishes, including girmabadam, zilviya, piti, a stew created with meat and potatoes and prepared in a terracotta pot.[40][55]

Language

The city of Shaki has developed its own dialect of Azerbaijani language, which is mainly spoken in the city, and the region of Shaki Rayon. Residents of city are known for their cheerful intonation of the words.

Museums

Shaki hosts a wealth of historical museums and some of the most important in the country. The Shaki History Museum is one of the main museums, considered one of the most important for artifacts of the Khanate period.[37]

As of the 18th century, five big Caravanserais (Isfahan, Tabriz, Lezgi, Ermeni and Taze) were active in Shaki but only two of them have survived.[20] The upper and lower Caravanserais were built in the 18th century and used by merchants to store their goods in cellars, who traded on the first floor, and lived on the second. Both Caravanserais includes view of all convenience and safety of merchants and their goods.[37]

Music and media

The city is home of the annual Mugham Festival and Silk Road International Music Festival.[56]

The regional channel Kanal-S, newspapers Shaki and Shakinin Sasi are headquartered in the city.[57]

Transport

There is a daily overnight train to and from Baku on the Baku - Balakan route

Education

Shaki branch of the Azerbaijan Pedagogical University, Sheki Regional College, 84 general and vocational schools operate in Shaki.[58]

Notable residents

The city's notable residents include: Fatali Khan Khoyski, prime minister of Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, Ahmadiyya Jabrayilov, an activist of the French Resistance, poet Bakhtiyar Vahabzadeh, composer Jovdat Hajiyev, film director Rasim Ojagov, actor Lutfali Abdullayev, religious leader Mahammad Hasan Movlazadeh Shakavi, and others.

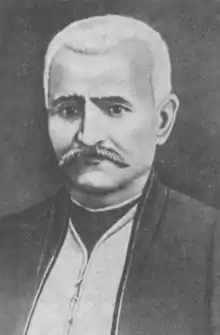

Mirza Fatali Akhundov, founder of materialism and atheism movement in Azerbaijan and modern Iranian literature, as well as one of the forerunners of Iranian nationalism

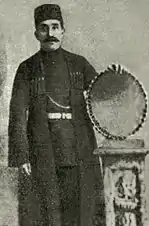

Mirza Fatali Akhundov, founder of materialism and atheism movement in Azerbaijan and modern Iranian literature, as well as one of the forerunners of Iranian nationalism Shakili Alasgar, mugham performer.

Shakili Alasgar, mugham performer. Abdulali bey Amirjanov, was member of Azerbaijani National Council.

Abdulali bey Amirjanov, was member of Azerbaijani National Council. Mahammad Hasan Movlazadeh Shakavi, the first scholar who translated Quran into the Azerbaijani language.

Mahammad Hasan Movlazadeh Shakavi, the first scholar who translated Quran into the Azerbaijani language. Fatali Khan Khoyski, the first Prime Minister of the independent Azerbaijan Democratic Republic.[59]

Fatali Khan Khoyski, the first Prime Minister of the independent Azerbaijan Democratic Republic.[59] Salman Mumtaz, Azerbaijani literary scholar and poet.

Salman Mumtaz, Azerbaijani literary scholar and poet.

Gallery

Ancient house in Shaki

Ancient house in Shaki Shaki House of Culture

Shaki House of Culture Front view of Albanian church

Front view of Albanian church One of the old streets of Shaki

One of the old streets of Shaki Door of Shaki Khan Palace

Door of Shaki Khan Palace A 6th-century Caucasian Albanian church

A 6th-century Caucasian Albanian church View of Shaki's Karavansarai

View of Shaki's Karavansarai Omer Efendi Mosque

Omer Efendi Mosque Shaki fortress

Shaki fortress Khan's Palace of Shaki

Khan's Palace of Shaki House of Shakikhanovs

House of Shakikhanovs Sheki Caravanserai

Sheki Caravanserai Ashagi Caravanserai

Ashagi Caravanserai House of Farhadbayovs

House of Farhadbayovs House of Alijanbayovs

House of Alijanbayovs Minaret of Friday mosque

Minaret of Friday mosque.jpg.webp) Ömər Əfəndi mosque

Ömər Əfəndi mosque Ağvanlar bath

Ağvanlar bath Undergraund bath in Shaki

Undergraund bath in Shaki Former Albanian church in Shaki

Former Albanian church in Shaki

Twin towns – sister cities

References

- "Shaki, Azerbaijan Page". Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- World Gazetteer: Azerbaijan – World-Gazetteer.com

- "Narinqala: Shaki's History". Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- "AZƏRBAYCAN MİLLİ ENSİKLOPEDİYASI". ensiklopediya.gov.az. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- "КЕРИМ АГА ФАТЕХ. КРАТКАЯ ИСТОРИЯ ШЕКИНСКИХ ХАНОВ. DrevLit.Ru - библиотека древних рукописей". drevlit.ru. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- оглы, Османов, Фазиль Латиф (8 June 2006). История и культура Кавказской Албании IV в. до н.э. - III в. н.э.: (на основании археологических материалов) (in Russian). Баку, «Тахсил».

- Буниятов, З. (1965). Азербайджан в VII-IX вв. Баку: Изд-во АН Азербайджанской ССР.

- "Sheki history". Azerbaijan Tour Agency. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- Musxelišvili, Davitʻ (1982). Из исторической географии восточной Грузии: Шаки и Гогарена (in Russian). Тбилиси: Изд-во "Мецниереба". OCLC 10925348.

- Encyclopaedia Iranica. Arrān

- "IL-KHANIDS – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Петрушевский, И. П. (1949). Государства Азербайджана в XV веке. Шеки в XV веке // Сборник статей по истории Азербайджана. Издательство Академии наук Азербайджанской ССР.

- "Shaki", in Historical Dictionary of Azerbaijan 1999, p. 117

- "History of Azerbaijan" (PDF).

- Uljaeva, Shohistahon. "Амир Темур в истории Азербайджана". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Nasiri, Ali Naqi; Floor, Willem M. (2008). Titles and Emoluments in Safavid Iran: A Third Manual of Safavid Administration. Mage Publishers. p. 279. ISBN 978-1933823232.

- var; ejwrote; Var, 2020-05-20 20:11:00; Var, Ej; Ej 2020-05-20 20:11:00. "Шеки (Нуха). Часть 1: Новый город и общий колорит". varandej.livejournal.com. Retrieved 7 January 2021.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Welcome to Heydar Aliyevs Heritage Research Center". lib.aliyev-heritage.org. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- "Shaki khanate".

- Sharifov, Azad. "Paradise in the Caucasus Foothills". azer.com. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- "History of Shaki" (PDF).

- "Welcome to Heydar Aliyevs Heritage Research Center". lib.aliyev-heritage.org. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Левиатов, В. (1948). Очерки из истории Азербайджана в XVIII веке,. Изд-во АН Азербайджанской ССР.

- "Khanate period".

- Абдуллаев, Г. (1958). Из истории Северо-Восточного Азербайджана в 60-80-х гг. XVIII в.,. Изд-во АН Азербайджанской ССР.

- Мустафаев, Дж. (1989). Северные ханства Азербайджана и Россия: конец XVIII-начало XIX века. «Элм».

- "Гюлистанский мирный договор 1813 года и Российская политика на Южном Кавказе в XIX веке". cyberleninka.ru. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Василий Потто (2006). Кавказская война. От древнейших времен до Ермолова. Москва: Центрполиграф.

- Şəki Şəhərinin Tarixi (in Azerbaijani)

- Рзаев Н. (1973). О происхождении Шеки и Нухи // Доклады Академии наук Азербайджанской ССР. Баку. p. 88.

- Эльдар Исмаилов. (2010). Очерки по истории Азербайджана. —. Издательство “Флинта”.

- "История Азербайджана :: Азербайджан XIX, XX, XXI вв". www.orexca.com. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- "Северный Азербайджан в период советской власти (1920-1991)". a-r.az. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- General Plan of Shaki City

- belediyye.io.ua General information about Shaki

- "Norwegians Help Restore Ancient Church". Azerbaijan International. Winter 2000. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- "Azerbaijan24: Sheki". Archived from the original on 13 December 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- Aliyarli, Suleyman. "The Great Silk Road and trade between the Caspian and Europe". www.visions.az. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- "Зарегистрировано увеличение туристического потока в Шекинский район". 1news.az. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- "SHEKİ DISTRICT". Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- "Təhsilimizin Hacı dayısı". Gunbaki. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- Ismayilli, Sevda. "Novella Cəfəroğlu: Referendumdan sonra elə gülürəm". azadlig.org. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- Gantz, Jeffrey. "On Chelsea waterfront, a moving story of motherhood". www.bostonglobe.com. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- "Welcome to Heydar Aliyevs Heritage Research Center". lib.aliyev-heritage.org. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- Саламзаде А. Р., Исмаилов А. И., Мамед-заде К. М. (1988). Шеки. Историко-архитектурный очерк / Под ред. М. А. Усейнова. Элм.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "История города Шеки - Афаг ТАИРОВА". Issuu. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- "CNN stops at Shaki City on the main Silk Road". teas.eu. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- Bayramova, Jeyran. "SHEKI'S MYSTERIES – STAINED GLASS AND THE SWEETEST HALVA". www.visions.az. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- "GENERAL INFORMATION ON AZERBAIJANI CULTURE". Embassy of Azerbaijan in Kuwait. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- Gink, Kalory (1979). Azerbaijan: Mosques, Turrets, Palaces. Corvina-Kiado. pp. 60–61.

- "Six cultural sites added to UNESCO's World Heritage List". UNESCO. 7 July 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- Mammadov, Farid (1994). Azerbaijan: Fortresses-Castles. Iterturan Inc. pp. 195–201.

- "Fortress and Summer Residence of the Khans of Sheki". Archnet.org. Archived from the original on 14 December 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- Т. А. Ханларов. (1972). Архитектура Советского Азербайджана. Москва: Стройиздат. p. 56.

- "SHAKI: WHAT TO EAT IN SHAKI". guidepicker.com. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- "5th International music festival "Silk Road" to open in Shaki". www.news.az. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- "Radio-TV yayımı" (in Azerbaijani). Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- "Şəki rayonu ümumi təhsil müəssisələri və internat məktəbi haqqında". www.sheki-ih.gov.az (in Azerbaijani). Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- "Presidential Library. Fatali Khan Khoyski" (PDF). p. 70. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- "Qardaşlaşmış şəhərlər". sheki-ih.gov.az (in Azerbaijani). Shaki. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shaki. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Sheki. |

_(semi-secession).svg.png.webp)