Eastern Alps

Eastern Alps is the name given to the eastern half of the Alps, usually defined as the area east of a line from Lake Constance and the Alpine Rhine valley up to the Splügen Pass at the Alpine divide and down the Liro River to Lake Como in the south. The peaks and mountain passes are lower than the Western Alps, while the range itself is broader and less arched.

| Eastern Alps | |

|---|---|

Piz Bernina (centre-left) with the Biancograt to the left, Piz Scerscen (centre-right) and Piz Roseg (right), seen from Piz Corvatsch | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Piz Bernina |

| Elevation | 4,049 m (13,284 ft) |

| Coordinates | 46°22′56.6″N 9°54′29.2″E |

| Dimensions | |

| Area | 130,000 km2 (50,000 sq mi) [1] |

| Geography | |

Delimitation of Western and Eastern Alps

| |

| Countries | Switzerland, Austria, Liechtenstein, Germany, Italy and Slovenia |

| Range coordinates | 46°34.5′N 12°13.9′E |

| Parent range | Alps |

| Borders on | Wienerwald, Transdanubian hills, Dinaric Alps, Venetian Plain, Po plain and Western Alps |

| Geology | |

| Orogeny | Alpine orogeny |

Geography

The Eastern Alps include the eastern parts of Switzerland (mainly Graubünden), all of Liechtenstein, and most of Austria from Vorarlberg to the east, as well as parts of extreme Southern Germany (Upper Bavaria), northwestern Italy (Lombardy), northeastern Italy (Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, Veneto and Friuli-Venezia Giulia) and a good portion of northern Slovenia (Upper Carniola and Lower Styria). In the south the range is bound by the Italian Padan Plain; in the north the valley of the Danube river separates it from the Bohemian Massif. The easternmost spur is formed by the Vienna Woods range, with the Leopoldsberg overlooking the Danube and the Vienna basin, which is the transition zone to the arch of the Carpathian Mountains.

The highest mountain in the Eastern Alps is Piz Bernina at 4,049 m (13,284 ft) in the Bernina Group of the Western Rhaetian Alps in Switzerland.[2] The sole four-thousander of the range, its name is taken from the Bernina Pass and was given in 1850 by Johann Coaz, who also made the first ascent. The rocks composing Piz Bernina are diorites and gabbros, while the massif in general is composed of granites (Piz Corvatsch, Piz Palü).[3] Excepting other peaks in the Bernina range, the next highest is the Ortler at 3,905 m (12,812 ft) in Italian South Tyrol and third the Großglockner at 3,798 m (12,461 ft), the highest mountain of Austria. The region around the Großglockner and the adjacent Pasterze Glacier has been a special protection area within the High Tauern National Park since 1986.[4]

Mount Sulzfluh is well frequented by climbers and is situated in the Rätikon range of the Alps, on the border between Austria and Switzerland. On the eastern side is a mountain path, of grade T4,[5] allowing non-climbers to reach the 2817 metre summit. There are six known caves in the limestone mountain, with lengths between 800 and 3000 or more yards, all with entrances on the Eastern side, in Switzerland.[6]

Mount Grauspitz (Vorder Grauspitze or Vorder Grauspitz on some maps) is the highest summit of the Rätikon, located on the border between Liechtenstein and Switzerland.

The Rätikon mountain range, in the Central Eastern Alps, derives its name from Raetia.

Only about 30% of Graubünden is commonly regarded as productive land, of which forests cover about a fifth of the total area.[7] The canton is entirely mountainous, comprising the highlands of the Rhine and Inn river valleys.[7] In its southeastern part lies the only official Swiss National Park. In its northern part the mountains were formed as part of the thrust fault that was declared a geologic UNESCO World Heritage Site, under the name Swiss Tectonic Arena Sardona, in 2008. Another Biosphere Reserve is the Biosfera Val Müstair adjacent to the Swiss National Park whereas Ela Nature Park is one of the regionally supported parks.

Classification

Geomorphology

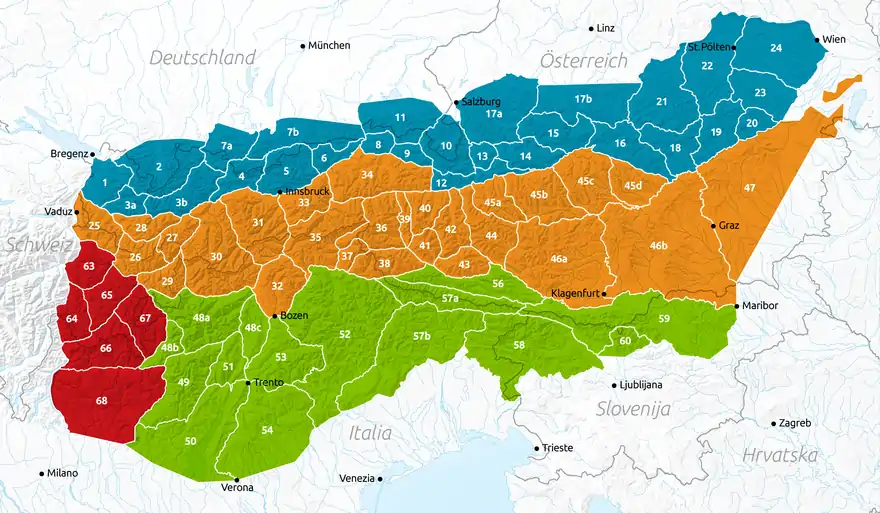

The ranges are subdivided by several deeply indented river valleys, mostly running east–west, including the Inn, Salzach, Enns, Adige, Drava and Mur valleys. According to the traditional Alpine Club classification of the Eastern Alps (AVE) widely used by Austrian and German mountaineers, these mountain chains comprise several dozen smaller mountain groups, each assigned to four larger regions:

- Northern Limestone Alps

- Central Eastern Alps

- Southern Limestone Alps

- Western Limestone Alps

For the breakdown of these regions into mountain groups see the List of mountain groups in the Alpine Club classification of the Eastern Alps. The Swiss Alpine Club (SAC) has a slightly different classification of the ranges, based on the political borders in the canton of Graubünden. In Italy the 1926 Partizione delle Alpi concept is quite common, recently superseded by the SOIUSA attempt to combine the different approaches. Other specific, especially hydrographical arrangements are also in use.

Tectonics

The Alps comprise four main nappe systems:

- The Helvetic nappes (Helveticum, French: Dauphiné), with their main ranges in the Western Alps. They consist primarily of Cretaceous and Paleogene sedimentary rocks in multiple folds.

- The Penninic nappes (Penninicum), Jurassic sediments of the Tethys Ocean stretching from the Eurasian to the Apulian Plate, pushed together during the Alpine orogeny. They comprise a Flysch zone and several crystalline rocks in geological windows, such as the Engadin window and the Hohe Tauern window in the Central Alps.

- The East Alpine system: the Northern Limestone Alps, made up of Mesozoic (Triassic) rocks, the Paleozoic slate (Kitzbühel and Salzburg Slate Alps) and the greywacke zone, as well as the crystalline Central Eastern Alps, the Precambrian and Paleozoic remnants of a main strike.

- The South Alpine system (Dinaric nappes) south of the Periadriatic Seam (Valtellina—Tonale Pass—Puster Valley—Gailtal—Karawanks). They mainly consist of Mesozoic and Paleozoic formations (Carnic Alps, Karawanks and several smaller strikes) with little faults, whose nappes and folds are oriented towards the south.

History

Ice age

During the Würm glaciation, the Eastern Alps were drier than the Western Alps, with the contiguous ice shield ending in the region of the Niedere Tauern in Austria. This allowed many species to survive the ice age in the Eastern Alps where they could not survive elsewhere. For that reason, many species of plants are endemic to the Eastern Alps.

Early history

A Bronze Age settlement at the site goes back as far as the Pfyn culture[8] (3900–3500 BC),[9] making Chur one of the oldest settlements in Switzerland. In ancient times, the area of what is today Ticino was settled by the Lepontii, a Celtic tribe. Later, probably around the reign of Augustus, it became part of the Roman Empire. By 259, Alamanni tribes had overran the Limes and caused widespread devastation of Roman cities and settlements. The Roman Empire succeeded in re-establishing the Rhine as the border, but it was now a frontier province. The late Roman influx from the north by the Alemanni also influenced the makeup of the Principality of Liechtenstein and is also evidenced by the remains of a Roman fort at Schaan.

Most of the lands of the region were once part of a Roman province called Raetia, which was established in 15 BC. The current capital of Graubünden, Chur, was known as Curia in Roman times. The area was later part of the diocese of Chur. A Roman road crossed Liechtenstein from south to north, traversing the Alps by the Splügen Pass and following the right bank of the Rhine at the edge of the floodplain, for long uninhabited because of periodic flooding. Some Roman villas have been excavated in Schaanwald and Nendeln. Nearly 2000 years later, some of the population of Graubünden still speak Romansh which has descended from Vulgar Latin.

In the 4th century Chur became the seat of the first Christian bishopric north to the Alps. Despite a legend assigning its foundation to a legendary British king, St Lucius, the first known bishop is one Asinio[10] in AD 451.

In ancient times, the region had long been inhabited by the Celts before it became part of the ancient Roman provinces of Raetia and Noricum. In the 6th century the Slavs settled the area, and the local dioceses collapsed. This is shown in archaeological culture. A Slavic language group was established in the area. The Alpine Slavs, who are reckoned to be ancestors of present-day Slovenes, also settled in the easternmost mountainous areas of Friuli, known as the Friulian Slavia, as well in as the Kras Plateau and the area north and south of Gorizia. At this time, Chur was also conquered by the Franks.[11] By the 590s AD, today's East Tyrol and Carinthia had come to be referred to in historical sources as Provincia Sclaborum (the Country of Slavs).[12][13] The territory settled by Slavs, however, was also inhabited by remnants of the indigenous Romanised Celtic and Pannonian population, who preserved the Christian faith and helped convert the Slavs of Carantania.

After the fall of the Ostrogothic Kingdom in 553, the Germanic tribe of the Lombards invaded Italy via the Tyrol and founded the Lombard Kingdom of Italy, which no longer included all of Tyrol, but only its southern part. The northern part of Tyrol came under the influence of the Bavarii, while the west was probably part of Alamannia.

Carantania was absorbed into the Frankish Empire in 745. The province of Lower Rhaetia was formed in 814.[14] Liechtenstein's borders have remained unchanged since 1434, when the Rhine was established as the border between the Holy Roman Empire and the newly formed Swiss cantons.

The city of Chur suffered several invasions: by the Magyars in 925–926, when the cathedral was destroyed, and by the Saracens (940 and 954), but afterwards it flourished thanks to its location, where the roads from several major Alpine transit routes come together and continue down the Rhine river. In 926 more Magyar raiders attacked the abbey and the nearby town of St Gallen.

Medieval history

In the years 1007 and 1027 the Emperors of the Holy Roman Empire granted the counties of Trento and Vinschgau to the Bishopric of Trent and the Bishopric of Brixen the county of Norital in 1027 and the Puster Valley in 1091 by the county of Milan and Como. By about 1100 Ticino was the centre of struggle between the free communes of Milan and Como.

The upper Rhine river had been visited by traders since Roman times, but acquired greater importance under the Ottonian dynasty of the Holy Roman Empire. Emperor Otto I appointed his vassal Hartpert as bishop of Chur in 958, and awarded the bishopric numerous privileges. In 1170 the bishop became a prince-bishop and kept total control over the road between Chur and Chiavenna. After the fall of the Western Empire, Ticino was ruled by the Ostrogoths, the Lombards and the Franks. Liechtenstein was under the Alamannii.

From upper Valais, the Walser began to spread south, west and east between the 12th and 13th centuries, in the so-called Walser migrations (Walserwanderungen).

In the 13th century Chur had some 1,300 inhabitants, and was surrounded by a line of walls. In 1367 the foundation of the Three Leagues in the area was a first step towards Chur's autonomy: a burgmeister (mayor) is first mentioned in 1413, and the bishop's residence was attacked by the inhabitants. Chur was the chief town of the Gotteshausbund or Chadé (League of the House of God), and one of the regular meeting places of the assemblies of the Leagues. As the power of the bishops, now increasingly under the influence of the nearby Habsburg County of Tyrol, decreased, in 1464 the citizens wrote a constitution which was adopted as the rule for the peoples of the local guilds and political positions.

The medieval county of Vaduz was formed in 1342 as a small subdivision of the Werdenberg county of the dynasty of Montfort of Vorarlberg.

In 1367 the League of God's House (Cadi, Gottes Haus, Ca' di Dio) was founded to resist the rising power of the Bishop of Chur. This was followed by the establishment of the Grey League (Grauer Bund), sometimes called Oberbund, in 1395 in the Upper Rhine valley.

In the 14th century it was acquired by the Visconti, Dukes of Milan. In the 15th century the Swiss Confederates conquered the valleys south of the Alps in three separate conquests.

Modern history

When Graubünden became a Swiss canton in 1803, Chur was chosen as its capital.

Mt. Piz Bernina (4,049 m) was given its name in 1850 by Johann Coaz, who also made the first ascent.[15]

The completion of the final portion of the FO railway occurred in 1926. It thus opened up the Cantons of Valais and Graubünden to further tourist development. This led to the introduction of Kurswagen (through coaches) between Brig and Chur, and between Brig and St. Moritz.[16]

Economy

Tourism in Graubünden is concentrated around the towns of Davos/Arosa, Flims and St. Moritz/Pontresina.[17]

See also

- Central Eastern Alps – also known as the Central Alps.

- Limestone Alps

- Periadriatic Seam

- Glarus thrust

References

- Umlauft, Friedrich (1889). The Alps. K. Paul, Trench & Company. p. 266.

- Piz Bernina, www.summitpost.org (accessed on May 2012)

- Geologic map of Switzerland 1:500 000, Bundesamt für Wasser und Geologie, CH-3003 Bern-Ittigen, ISBN 3-906723-39-9

- A. Tschugguel. "Das Sonderschutzgebiet"Großglockner-Pasterze"" (PDF). Österreichischer Alpenverein. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2009.

- "Hiking in Switzerland, degree of difficulty". Archived from the original on 2011-05-15.

- Biological report about Cave bear in the caves. (German)

- Federal Department of Statistics (2008). "Regional Statistics for Graubünden". Archived from the original on 2009-04-14. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- Pre-Roman History in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Schibler, J. 2006. The economy and environment of the 4th and 3rd millennia BC in the northern Alpine foreland based on studies of animal bones. Environmental Archaeology 11(1): 49–65

- Religious life in the Alps, Switzerland Historical Dictionary Archived 2009-08-24 at the Wayback Machine (in Italian)

- Franks, page at Switzerland Historical Dictionary

- Oto Luthar, ed., "The Land Between: A History of Slovenia". Frankurt am Main [etc.]: Peter Lang, cop. 2008. ISBN 978-3-631-57011-1.

- Paulus Diaconus, "Historia Langobardorum".

- Liechtenstein - History www.nationsencyclopedia.com (accessed on May 2012)

- Collomb, Robin, Bernina Alps, Goring: West Col Productions, 1988, p. 55.

- Moser, Beat; Börret, Ralph; Küstner, Thomas (2005). Glacier Express: Von St. Moritz nach Zermatt. Fürstenfeldbruck, Germany: Eisenbahn-Journal (Verlagsgruppe Bahn GmbH). ISBN 3-89610-057-2., page 102. (in German)

- Switzerland holidays Graubünden winter

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |