Economy of ancient Tamil country

The economy of the ancient Tamil country (Sangam era: 500 BCE – 300 CE) describes the ancient economy of a region in southern India that mostly covers the present-day states of Tamil Nadu and Kerala. The main economic activities were agriculture, weaving, pearl fishery, manufacturing and construction. Paddy was the most important crop; it was the staple cereal and served as a medium of exchange for inland trade. Pepper, millets, grams and sugarcane were other commonly grown crops. Madurai and Urayur were important centers for the textile industry; Korkai was the center of the pearl trade. Industrial activity flourished.

Inland trading was conducted primarily through barter in busy market places by merchant associations and commercial lending institutions. Merchants formed associations that operated autonomously, without interference from the state. The people of ancient Tamil country engaged in brisk overseas trade with Rome; the trade reached a peak after the discovery of a direct route for merchant ships between Tamilakam and Egypt, taking advantage of the monsoon winds. Pepper, pearls, ivory, textiles and gold ornaments were exported from Tamilakam, and the main imports were luxury goods such as glass, coral, wine and topaz. Foreign trade brought in a large amount of internationally convertible Roman currency.

The state played an important role in building and maintaining infrastructure such as roads and ports—funded through taxation—to meet the needs of economic and social activity. Wealth was unequally divided among the people, giving rise to distinct economic classes.

Agriculture

Agriculture was the main occupation of the ancient Tamils and the most respected.[1][2] Farmers were aware of different soil types, the best crops to grow and the various irrigation systems suitable for any given region. In the five geographical divisions of the Tamil country in Sangam literature, the Marutam region was the most fit for cultivation, as it had the most fertile lands. Land was classified, according to its fertility, as Menpulam (fertile land), Pinpulam (dry land), Vanpulam (hardland) and Kalarnilam or Uvarnilam (salty land). Menpulam yielded rich produce on a variety of crops, but Pinpulam was cultivated only with dry crops due to limited irrigation facilities. The yield from Vanpulam was limited, while Kalarnilam was unfit for cultivation. Some of the well known types of soil were alluvial soil, red soil, black soil, laterite soil and sandy soil.[3]

The Tamils cultivated paddy, sugarcane, millets, pepper, various pulses, coconuts, beans, cotton, plantain, tamarind and sandalwood. Paddy was the main crop, with different varieties grown in the wetland of Marutam, such as Vennel, Sennel, Pudunel, Aivananel and Torai. The peasants lived in groves of trees close to the farmlands and each house had jack, coconut, palm, areca and plantain trees. Peasants grew turmeric plants in front of their houses and laid flower gardens in between the houses. Farmers believed that ploughing, manuring, weeding, irrigation and the protection of crops must be done according to a specific method in order to obtain a good yield.[4] A wide range of tools needed for agriculture, from ploughing to harvesting, were manufactured. The basic tool was the plough also known as meli, nanchil and kalappai. Palliyadutal referred to the process of removing weeds using a toothed implement attached to a plank and drawn by oxen. Lower-class peasants used stone sling devices to scare animals and birds away from the standing crops. Sickles were used for harvesting mature rice paddies.[5] Since the rivers of the region were not perennial, several irrigation techniques were developed to ensure an adequate and continuous supply of water. Farmers used a bullock-propelled device called Kapilai for bailing out water from deep wells and a manual setup called Erram, for shallow wells. Tanks, lakes and dams were used as water storage systems and the water regulated using sluices and shutters.[5] Kallanai, a dam built on river Kaveri during this period, is one of the oldest water-regulation structure in the world.[6][7][8] Surface irrigation, sprinkler mechanism and drip irrigation methods were followed to prevent wastage of water.[9]

Most farmers cultivated their own plots of land and were known by different names such as Mallar, Ulutunbar, Yerinvalnar, Vellalar, Karalar and Kalamar.[10] There were also absentee landlords who were mostly brahmins and poets who had received donations of land from the king and who gave these donations to tenant farmers. Sometimes independent farm laborers, known as Adiyor, were hired for specific tasks. Landlords and peasants paid tax on the land and its produce – the land tax was known as Irai or Karai and the tax on produce was called Vari. One sixth of the produce was collected as tax.[11] Taxes were collected by revenue officials known as Variya and Kavidi, who were assisted by accountants called Ayakanakkar. For survey and taxation purposes, various measurements were used to measure the land and its produce. Small lots of land were known as Ma and larger tracts as Veli. Produce was measured using cubic-measures such as Tuni, Nali, Cher and Kalam and weight-measures such as Tulam and Kalanju.

Industry

During the Sangam age, crafts and trade occupations were considered secondary to agriculture. Carpenters crafted wooden wares and blacksmiths worked in simple workshops. Weaving, pearl fishing, smithy and ship building were prominent industries of ancient Tamilakam. Spinning and weaving was a source of income for craftsmen; weaving was practised part-time by the farmers in rural areas. Madurai and Urayur were important industrial centers, known for their cotton textiles. Muslin cloth was woven with fine floral work of different colors. Silk cloth was manufactured with its threads gathered in small knots at its ends. Clothing was embroidered for the nobles and aristocrats who were the main customers. Material was often dyed; the blue dye for the loin cloth was a preferred color. In addition to silk and cotton fabrics, cloth made of wood fibre called Sirai Maravuri and Naarmadi was used by the priestly class.[12] The cloth manufacturers wove long pieces of cloth and delivered it to the dealers. The textile dealers then scissored off bits of required length, called aruvai or tuni, at the time of sale. Hence, the dealers were called aruvai vanigar and the localities where they lived aruvai vidi. Tailors, called tunnagarar in Madurai and other big towns, stitched garments .[13]

Pearl fishing flourished during the Sangam age. The Pandyan port city of Korkai was the center of the pearl trade. Written records from Greek and Egyptian voyagers give details of the pearl fisheries off the Pandyan coast. According to one account, the fishermen who dove into the sea avoided attacks from sharks by bringing up the right-whorled conch and blowing on the shell.[14] Convicts were used as pearl divers in Korkai. The Periplus mentions that "Pearls inferior to the Indian sort are exported in great quantity from the marts of Apologas and Omana".[15] Pearls were woven together with muslin cloth before being exported and were the most expensive product imported by Rome from India.[15] The pearls from the Pandyan kingdom were in demand in the kingdoms of North India as well. Several Vedic mantras refer to the wide use of the pearls, describing poetically that royal chariots and horses were decked with pearls. The use of pearls was so great that the supply of pearls from the Ganges could not meet the demand.[16]

The blacksmith, working in the Panikkalari (literally: workplace), played an important role in the lives of ancient Tamils. Some of the essential items produced by blacksmiths were weapons of war, tools such as the plough, domestic utensils and iron wheels. They used a blow pipe or a pair of bellows (a turutti) to light the fire used for smelting and welding. There were not many blacksmith shops in the rural areas. Blacksmiths were overworked as they had to serve the needs of neighboring villages.[17] Shipbuilding was a native industry of Tamilakam. Ocean craft of varying sizes, from small catamarans (logs tied together) to big ships, navigated Tamil ports. Among the smaller crafts were ambi and padagu used as ferries to cross rivers and the timil, a fishing boat. Pahri, Odam, Toni, Teppam, and Navai were smaller craft. The large ship, called Kappal, had masts (Paaymaram) and sails (Paay).[18][19]

Other industries were carpentry, fishing, salt-manufacture, forestry, pottery, rope making, chank-cutting, gem cutting, the manufacture of leather sheaths for war weapons, the manufacture of jewellery, the production of jaggery, and the construction of temples, and other religion-related items such as procession cars and images. Baskets made of wicker for containing dried grains and other edible articles were also constructed.[20][21]

Inland trade

Ancient IND were active traders in various commodities, both locally and outside Tamil country. The kingdoms of northern India sought pearls, cotton fabrics and conch shells from Tamilakam in exchange for woollen clothing, hides and horses.[22] Locally most trading was in food products – agricultural produce was supplemented by products from hunters, fishermen and shepherds who traded in meat, fish and dairy products. In addition, people bought other goods such as items for personal hygiene, adornment and transportation. Mercantile transactions took place in busy market places. Traders used various modes of selling: hawking their goods from door to door, setting up shops in busy market places or stationing themselves at royal households. Sellers of fish, salt and grain hawked their goods, the textile merchants sold cloths from their shops in urban markets and the goldsmith, the lapidary and sellers of sandalwood and ivory patronised the aristocrats' quarters.[12] Merchants dealt in conches and ivory.

Most trade was by barter. Paddy was the most commonly accepted medium of exchange, followed by purified salt. Honey and roots were exchanged for fish liver oil and arrack, while sugarcane and rice flakes were traded for venison and toddy. Poems in Purananuru describe the prosperous house in Pandya land well stocked with paddy that the housewife had exchanged for grams and fish. Artisans and professionals traded their services for goods.[21] Quantities were measured by weighing balance, called the Tulakkol named after Tulam, the standard weight. Delicate balances made of ivory were used by the goldsmiths for measures of Urai, Nali and Ma.[23] A different kind of barter involving deferred exchange was known as Kuri edirppai – this involved taking a loan for a fixed quantity of a commodity to be repaid by the same quantity of the same commodity at a later date. Since barter was prevalent locally, coins were used almost exclusively for foreign trade.

Markets

Sangam works such as Maduraikkanci and Pattinappalai give a detailed description of the markets in big cities.[24][25] The market, or angadi, was located at the centre of a city.[26] It had two adjacent sections: the morning bazaar (nalangadi) and the evening bazaar (allangadi). The markets of Madurai were cosmopolitan with people of various ethnicities and languages crowding into the shops. Foreign merchants and traders came to Madurai from such northern kingdoms as Kalinga to sell merchandise wholesale.[27] According to the Mathuraikkanci, the great market was held in a large square and the items sold included garlands of flowers, fragrant pastes, coats with metallic belts, leather sandals, weapons, shields, carts, chariots and ornamented chariot steps. Garment shops sold clothing of various colours and patterns made of cotton, silk or wool, with the merchandise neatly arranged in rows. On the grain merchants' street, sacks of pepper and sixteen kinds of grains (including paddy, millet, gram, peas and sesame seeds) were heaped by the side. The jewellers, who conducted business from a separate street, sold precious articles such as diamonds, pearls, emeralds, rubies, sapphires, topaz, coral beads and varieties of gold.[25]

Vanchi, the capital of the Cheras, was a typical fortified city, with two divisions inside the fort – the Puranakar and the Akanakar. The Puranakar was the outer city adjacent to the fort wall and was occupied by the soldiers. The Akanakar, the inner city, included the king's palace and the officers' quarters. The city market was located between these two divisions; the artisans and traders lived close to the market.[28] Kaveripumpattinam, the port city of the Cholas, had its market in a central open area close to the two main suburbs of the city – Maruvurpakkam and Pattinapakkam. Maruvurpakkam was adjacent to the sea where the fishermen and the foreign merchants lived. The main streets of the market met at the centre where there was a temple dedicated to the local guardian deity of the city.[29]

The market of Kaveripumpattinam was similar to the one in Madurai. Large quantities of dyes, scented powder, flowers, textiles, salt, fish and sheep were sold. Flowers were in great demand, especially during festivals such as Indira vizha. Near the bazaar were warehouses with little ventilation located underground. Since merchants from various places thronged the bazaar, each package for sale had the name and details of its owner written on it. Simple advertisements were used to indicate the goods available at different locations.[30]

Mercantile organization

There were different types of merchants who operated in the ancient Tamil market, which gave rise to a wealth-based class distinction among them. Merchants in the lower levels of the hierarchy were of two varieties: the itinerant merchants who sold goods that they manufactured themselves and the retailers who sold goods manufactured by others. Itinerant traders were found in both the rural and urban markets, but the retailers were concentrated in the cities. In the rural markets, salt and grain merchants usually produced the goods, transported them and sold them directly to the consumers. Salt merchants, known as umanar, travelled with their families in trains of carts.[12] In the cities, artisans such as the blacksmiths and the oil mongers sold their products directly to the consumers. The bulk of the retailers operated in the textile industry. The textile dealers (aruvai vanigar) bought their products from the weavers (kaarugar) and resold them to the consumers. Merchants selling agricultural produce in the cities were also retailers. At the upper end of the merchant hierarchy, were the rich merchants who participated in the export trade. There were three classes among them - ippar, kavippar and perunkudi - based on the extent of their wealth; the perunkudi made up the wealthiest class. Foreign merchants, mainly Romans, also did business in the Tamil markets – not just in the port cities, but in inland cities such as Madurai, where they exchanged indigenous goods for their offerings. Another category of merchants were the intermediaries or the brokers, who acted as information channels and offered their services mainly to the foreign merchants.[31]

Merchants organized themselves into groups called Sattu or Nikamam. Stone inscriptions at Mangulam (c. 200 BCE) and pottery inscriptions found at Kodumanal refer to merchant guilds as nikamam and the members of the guilds as nikamattor. These findings suggest that merchant guilds were established at several industrial and trade centres of ancient Tamil country.[32] Many of these merchant associations acted in union in their public activities. They were autonomous, meaning that they enjoyed freedom from state interference but also suffered from the lack of state backing. Merchants were expected to abide by a code of conduct, which was: "Refuse to take more than your due and never stint giving to others their due". Therefore, they went about running their business by openly announcing the profit they were aiming at, known as Utiyam.[12][33] The mercantile community of Tamilakam was aware of elementary banking operations. Lending through houses specializing in monetary transactions and fixation of rates were common. This was, evidently, necessitated by the extensive overseas trade.[34] Accountants were in demand in view of monetary transactions and considerable trading activity.[35] Merchant groups from Madurai and Karur made endowments, or donations, as attested by inscriptions found in Alagarmalai (c. 1st century BCE) and Pugalur (c. 3rd century CE). These inscriptions also mention that the various commodities traded by such merchants included cloth, salt, oil, plowshares, sugar and gold.[32]

Foreign trade

The economic prosperity of the Tamils depended on foreign trade. Literary, archaeological and numismatic sources confirm the trade relationship between Tamilakam and Rome, where spices and pearls from India were in great demand. With the accession of Augustus in 27 BCE, trade between Tamilakam and Rome received a tremendous boost and culminated at the time of Nero who died in 68 CE. At that point, trade declined until the death of Caracalla (217 CE), after which it almost ceased. It was revived again under the Byzantine emperors. Under the early Roman emperors, there was a great demand for articles of luxury, especially beryl. Most of the articles of luxury mentioned by the Roman writers came from Tamilakam. In the declining period, cotton and industrial products were still imported by Rome.[36] The exports from the Tamil country included pepper, pearls, ivory, textiles and gold ornaments, while the imports were luxury goods such as glass, coral, wine and topaz.[37] The government provided the essential infrastructure such as good harbours, lighthouses, and warehouses to promote overseas trade.[38]

Trade route

The trade route taken by ships from Rome to Tamilakam has been described in detail by the writers, such as Strabo and Pliny the Elder. Roman and Arab sailors were aware of the existence of the monsoon winds that blew across the Indian Ocean on a seasonal basis. A Roman captain named Hippalus first sailed a direct route from Rome to India, using the monsoon winds. His method was later improved upon by merchants who shortened the voyage by sailing due east from the port of Cana or Cape Guardafui, finding that by this way it was possible to go directly from Rome to Tamilakam. Strabo writes that every year, about the time of the summer solstice, a fleet of one hundred and twenty vessels sailed from Myos Hormos, a port of Egypt on the Red Sea, and headed toward India. With assistance from the monsoons, the voyage took forty days to reach the ports of Tamilakam or Ceylon. Pliny writes that if the monsoons were blowing regularly, it was a forty-day trip to Muziris[39] from Ocelis located at the entrance to the Red Sea from the south. He writes that the passengers preferred to embark at Bacare (Vaikkarai) in Pandya country, rather than Muziris, which was infested with pirates. The ships returned from Tamilakam carrying rich cargo which was transported in camel trains from the Red Sea to the Nile, then up the river to Alexandria, finally reaching the capital of the Roman empire.[40] Evidence of Tamil trading presence in Egypt is seen in the form of Tamil inscriptions on pottery in Red Sea ports.

Imports and exports

Fine muslins and jewels, especially beryls (vaiduriyam) and pearls were exported from Tamilakam for personal adornment. Drugs, spices and condiments as well as crape ginger and other cosmetics fetched high prices. Even greater was the demand for pepper which, according to Pliny, sold at the price of 15 denarii (silver pieces) a pound. Sapphire, called kurundham in Tamil, and a variety of ruby were also exported. The other articles exported from Tamilakam were ivory, spikenard, betel, diamonds, amethysts and tortoiseshell. The Greek and Arabic names for rice (Oryza and urz), ginger(Gingibar and zanjabil) and cinnamon (Karpion and quarfa) are almost identical with their Tamil names, arisi, inchiver and karuva.[41] The imports were mostly luxury items such as glass, gold and wine. Horses were imported from Arabia.[22]

Foreign exchange

The flourishing trade with the Romans had a substantial impact on the economy of ancient Tamil country and the royal treasury and the export traders accumulated large sums of Roman currency. Pliny writes that India, China and Arabia between them absorbed one hundred million sesterces per annum from Rome. This sum is calculated by Mommsen to represent 1,100,000 pounds, of which nearly half went to India, the preponderance to South India.[42]

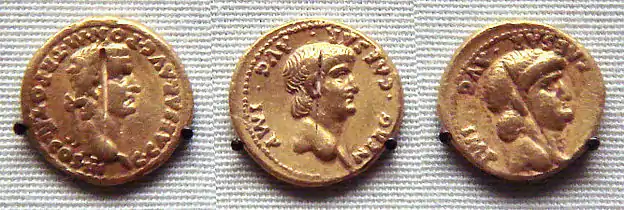

Coins hoarded by the early Roman emperors from Augustus to Nero have been found in the vicinity of the South Indian beryl mines which produced the best and purest beryl in the world. At fifty-five different locations, mostly in Madurai and Coimbatore districts, these coins have been unearthed; the number of gold coins discovered has been described as a quantity amounting to five coolly loads. The quantity of silver coins has been variously described as "a great many in a pot", "about 500 in an earthen pot", "a find of 163 coins", "some thousands enough to fill five or six Madras measures". Coins of all the Roman emperors from Augustus (27 BCE) to Alexander Severus (235 CE]) have been discovered, covering a period of nearly three centuries. By far the greatest number of these Roman coins belong to the reigns of Augustus and Tiberius. After 235 CE, for the next one hundred years, there are no coins that can be dated, suggesting a temporary abeyance of trade between Rome and South India. This could have been due to internal revolts and external attacks suffered by the Roman empire during that period. When order and good government were restored in Rome, trade with Tamilakam revived, as indicated by the finding of an increased number of coins from this period. Zeno's coins have been traced to the end of the Roman empire. Scholars believe there was a Roman settlement near Madurai and that little copper coins with the Roman Emperors' heads on them might have been minted locally.[42]

Role of the state

The role of the state in trade related to two aspects: first, to provide an adequate infrastructure necessary to sustain the trade and second, to organise an efficient administrative apparatus for taxation.[43]

During the Sangam period, the main trade routes, such those going over the Western Ghats, went through thick forests. It was the duty of the state to protect the merchant caravans on these trade routes from robbers and wild life. Main roads, known as Peruvali, were built that connected the distant parts of the country. These roads were as important to the army as they were to the merchants. Commodities like salt had to be transported long distances, such as from the sea coast to the interior villages. The state also built and expanded the infrastructure for shipping such as ports, lighthouses and warehouses near the ports to promote overseas trade. Several ports were constructed on both the east and the west coasts of Tamilakam. Kaveripumpattinam (also known as Puhar) was the chief port of the Cholas; their other ports were Nagapattinam, Marakkanam and Arikamedu, all on the east coast. The Pandyas had developed Korkai, Saliyur, Kayal, Marungurpattinam (present day Alagankulam) and Kumari (present day Kanyakumari) as their centers of trade along the east coast, while Niranam and Vilinam were their west coast ports. Muchiri, Tondi, Marandai, Naravu, Varkkalai and Porkad were the principal ports of the Cheras, all of them on the west coast.[44]

To collect revenue from commerce, the state installed customs checkposts (sungachavadi) along the highways and the ports. In the ports, duty was collected on inland goods, before being exported, and on overseas goods meant for the local markets, which were stamped with the official seal before being allowed into the country. The volume of trade in the port cities was high enough to warrant a large workforce to monitor and assess the goods. The state issued licenses to liquor shops, which were required to fly the license flag outside their premises. Flags were used by foreign merchants too, to indicate the nature of goods they were selling. The state also kept records of the weights and counts of all the goods sold by merchants. One of the significant aspects of the state intervention in commerce was that it reinforced the authority of the ruler.[43]

Personal wealth

How wealth was assessed varied from one community to another. Farmers counted the number of ploughshares owned and among the pastoral folk it was the number of cows. Wealth was distributed unequally among the people, leading to distinct economic classes - the rich, the poor and the middle class. The nobility, state officers, export traders and court poets formed the wealthy class. Most agriculturists and inland merchants made up the middle class. The lowest class consisted of labourers and wandering minstrels. It was believed that this economic division of people was the result of a divine arrangement; the poor people were made to feel that their miserable condition was due to their past sins, tivinai, and was inevitable.[45] The extreme opulence of some people as well as the abject poverty of some others are clearly portrayed in the contemporary literature. Most of the rich spent a part of their wealth on charity, the king's philanthropy setting an example. It was believed that one needed to accumulate wealth in order to give donations and perform righteous obligations. Sometimes, the men of the household undertook a long journey to the north of the Venkata Hill or the northern boundary of Tamilakam, to earn wealth. One possible region that they might have gone to is the Mysore region, where the gold mines were getting famous. F. R. Allchin, who has discussed the antiquity of gold mining in the Deccan, says that the high period of mining in South India was the last centuries of the pre-Christian era and the first two centuries of the Christian era, which coincides with the Sangam period.[46]

Sources

| Part of a series on |

| History of Tamil Nadu |

|---|

|

The most important source of ancient Tamil history is the corpus of Tamil poems, referred to as Sangam literature, dated between the last centuries of the pre-Christian era and the early centuries of the Christian era.[47][48][49] It consists of 2381 known poems, with a total of over 50000 lines, written by 473 poets.[50][51] Each poem belongs to one of two types: Akam (inside) and Puram (outside). The akam poems deal with inner human emotions such as love, while the puram poems deal with outer experiences such as society, culture and warfare. These poems contain descriptions of various aspects of life in the ancient Tamil country. The Maduraikkanci by Mankudi Maruthanaar and the Netunalvatai by Nakkirar contain a detailed description of the Pandyan capital Madurai, the king's palace and the rule of Nedunj Cheliyan, the victor of the Talaialanganam battle.[52] The Purananuru and Agananuru collections contain poems sung in praise of various kings and poems that were composed by the kings themselves. The Pathirruppaththu provides the genealogy of two collateral lines of the Cheras and describes the Chera country. The Pattinappaalai talks about the riches of the Chola port city of Kaveripumpattinam and the economic activities in the city. The historical value of the Sangam poems has been critically analysed by scholars in the 19th and 20th centuries. Historians agree that the descriptions of society, culture and economy in the poems are authentic, for the most part: many eminent scholars including Sivaraja Pillay, Kanakasabhai, K.A.N Sastri and George Hart have used information from these poems to describe the ancient Tamil society.[53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60] Herman Tieken, a Dutch scholar, has expressed his disapproval of doing so, arguing that the poems were composed much later in the 8th-9th centuries CE.[61] Tieken's methodology and his conclusions about the date of Sangam poems have been criticized by other scholars.[62][63][64]

Among literary sources in other languages, the most informative ones are Greek and Roman accounts of the maritime trade between the Roman empire and the kingdoms of Tamilakam. Strabo and Pliny the Elder give the details of the trade route between the Red Sea coast and the western coast of South India. Strabo (c. 1st century BCE) mentions the embassies sent by the Pandyas to the court of Augustus, along with a description of the ambassadors. Pliny (c. 77 CE) talks about the different items imported by the Romans from India and complains about the financial drain caused by them. He also refers to many Tamil ports in his work The Natural History. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (c. 60 - 100 CE) an anonymous work, gives an elaborate description of the Tamil country and the riches of a 'Pandian Kingdom'.

Archaeological excavations at many sites in Tamil Nadu including Arikamedu, Kodumanal, Kaveripumpattinam and Alagankulam, have yielded a variety of artifacts belonging to the Sangam era, such as various types of pottery and other items including black and red ware, rouletted ware, Russet coated ware, brick walls, ring wells, pits, industrial items, and the remains of seeds and shells.[65][66][67][68] Many of the pottery sherds contain Tamil-Brahmic inscriptions on them, which have provided additional evidence for the archaeologist to date them. Archaeologists agree that activities best illustrated in these material records are trade, hunting, agriculture and crafts.[69] These excavations have provided evidence for the existence of the major economic activities mentioned in Sangam literature. Remnants of irrigation structures like reservoirs and ring wells and charred remains of seeds attest to the cultivation of different varieties of crops and knowledge of various agricultural techniques.[70][71][72][73] Spinning whorls, cotton seeds, remains of a woven cotton cloth and dyeing vats provide evidence for the activities of the textile industry.[74][75] Metallurgy has been supported by the discovery of an ancient blast furnace, along with its base and wall, anvil, slags and crucibles. The remains have indicated that, in addition to iron, the blacksmith may have worked with steel, lead, copper and bronze.[76] The Kodumanal excavation recovered several jewellery items and semi precious stones at different stages of manufacture, suggesting that they were locally manufactured.[77] Remains of import and export articles recovered from Arikamedu indicate the important role it played as an Indo-Roman trading station.[78] Building construction, pearl fishery and painting are other activities that have been supported by findings from these excavations.[73][79][80][81]

Inscriptions are another source of deducing ancient Tamil history: most of them are written in Tamil-Brahmi script and found on rocks or pottery. The inscriptions have been used to corroborate some of the details provided by the Sangam literature. Cave inscriptions found at places such as Mangulam and Alagarmalai near Madurai, Edakal hill in Kerala and Jambai village in Villupuram district record various donations made by the kings and chieftains.[82] Brief mentions of various aspects of the Sangam society such as agriculture, trade, commodities, occupations and names of cities are found in these inscriptions.[83] Several coins issued by the Tamil kings of this age have been recovered from river beds and urban centers of their kingdoms. Most of them carry the emblem of the corresponding dynasty, such as the bow and arrow of the Cheras; some of them contain portraits and written legends. Numismatists have used these coins to establish the existence of the Tamil kingdoms during the Sangam age and associate the kings mentioned in the legends to a specific period.[84] A large number of Roman coins have been found in Coimbatore and Madurai districts, providing more evidence for the brisk maritime trade between Rome and Tamilakam.[85]

See also

Notes

- Venkata Subramanian (1988), p. 26.

- "Thirukkural".

உழுதுண்டு வாழ்வாரே வாழ்வார்மற் றெல்லாம் தொழுதுண்டு பின்செல் பவர். They live who live to plough and eat; The rest behind them bow and eat.

- Balambal (1998), p. 60.

- Pillai (1972), pp. 50–51.

- Pillai (1972), p. 51.

- Balambal (1998), p. 64.

- Singh, Vijay P.; Ram Narayan Yadava (2003). Water Resources System Operation: Proceedings of the International Conference on Water and Environment. Allied Publishers. p. 508. ISBN 81-7764-548-X.

- "This is the oldest stone water-diversion or water-regulator structure in the world" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2007. Retrieved 27 May 2007.

- Balambal (1998), p. 65.

- Balambal (1998), p. 61.

- Balambal (1998), p. 67.

- Venkata Subramanian (1988), p. 86.

- Subrahmanian (1980), pp. 240–241.

- Caldwell, Robert (1881). A Political and General History of the District of Tinnevelly. Asian Educational Services. p. 20. ISBN 978-81-206-0145-1. Retrieved 15 July 2005.

- Venkata Subramanian (1988), p. 55.

- Iyengar, P.T. Srinivasa (2001). History Of The Tamils: From the Earliest Times to 600 AD. Asian Educational Services. p. 22. ISBN 978-81-206-0145-1. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- Subrahmanian (1980), p. 241.

- Sundararajan. p. 85. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Subrahmanian (1980), p. 253.

- Subrahmanian (1980), p. 356.

- Sivathamby. pp. 173–174. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Krishnamurthy. pp. 5–6. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Venkata Subramanian (1988), p. 87.

- Venkata Subramanian (1988), p. 45.

- Husaini. p. 24. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Venkata Subramanian (1988), p. 81.

- Subrahmanian (1980), pp. 244–245.

- Venkata Subramanian (1988), pp. 75–76, 80.

- Venkata Subramanian (1988), pp. 71, 80.

- Subrahmanian (1980), p. 254.

- Mukund. pp. 17–19. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Mahadevan. p. 141. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Subrahmanian (1980), p. 246.

- Subrahmanian (1980), p. 360.

- Subrahmanian (1980), p. 357.

- Husaini. p. 20. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Krishnamurthy. p. 6. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Subrahmanian (1980), p. 359.

- Staff Reporter. "More studies needed at Pattanam". The Hindu.

- Husaini. p. 18. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Husaini. p. 19. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Husaini. pp. 20–21. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Mukund. pp. 22–23. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Krishnamurthy. p. 5. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Subrahmanian (1980), p. 232.

- Sivathamby. p. 175. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Subrahmanian (1980), p. 22.

- Sharma, TRS (2000). Ancient Indian Literature: An Anthology. Vol III. Sahitya Academy, New Delhi. p. 43.

- "Cankam literature". The Encyclopædia Britannica. 2. 2002. p. 802.

- Rajam, V. S. 1992. A reference grammar of classical Tamil poetry: 150 B.C.-pre-fifth/sixth century A.D. Memoirs of the American philosophical society, v. 199. Philadelphia, Pa: American Philosophical Society. p12

- Dr. M. Varadarajan, A History of Tamil Literature, (Translated from Tamil by E.Sa. Viswanathan), Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi, 1988 p.40

- Sastri. A History of South India from Prehistoric Times to the Fall of Vijayanagar. p. 127.

- Pillay, Sivaraja. p. 11. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Venkata Subramanian (1988), pp. 12–13.

- Subrahmanian (1980), p. 23.

- Sundararajan. p. 3. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Pillai (1972), p. 8.

- Sastri. The Pandyan Kingdom. pp. 14–15, 21, 31.

- Mukund. p. 24. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Husaini. p. 7. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Tieken, Herman Joseph Hugo (2001) Kāvya in South India: old Tamil Caṅkam poetry. Groningen: Egbert Forsten. pp. 229-230

- Hart, George (2004). "Kāvya in South India: Old Tamil Caṅkam Poetry by Herman Tieken". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 124 (1): 180–184. doi:10.2307/4132191. JSTOR 4132191.

- G.E. Ferro-Luzzi. Tieken, Herman, Kavya in South India (Book review). Asian Folklore Studies. June 2001. pp. 373-374

- Anne E. Monius, Book review, The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 61, No. 4 (Nov., 2002), pp. 1404-1406

- Begley, p. 461

- Rajan, p. 57

- Tripati et al., pp. 86, 89

- Gaur and Sundaresh, pp. 126-7

- Abraham, p. 219

- Cooke et al., pp. 342-3, 348-9

- Tripati et al., pp. 86-88

- Gaur and Sundaresh, p. 124

- Begley, p. 472

- Rajan, p. 67

- Begley, p. 475

- Rajan, pp. 65-66, 95, 98-102

- Rajan, pp. 66-67

- Begley, pp. 472, 480

- Tripati et al., pp. 86, 88-89

- Gaur and Sundaresh, p. 127

- Rajan, p. 141

- Mahadevan, pp. 7-24

- Mahadevan, pp. 115-159

- Krishnamurthy, pp. 20-23, 97-107, 132-148

- Husaini, pp. 20-21

References

|

|