Muslin

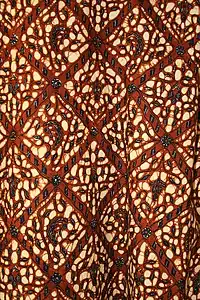

Muslin (Bengali: মসলিন) (/ˈmʌzlɪn/) is a cotton fabric of plain weave.[1][2] It is made in a wide range of weights from delicate sheers to coarse sheeting.[2][3] It gets its name from the city of Mosul, Iraq which the Europeans believed to be its place of origin, however, its origins have now proved to have been farther east — in particular Dhaka in Bangladesh.[3][4][5][2]

Early muslin was handwoven of uncommonly delicate handspun yarn, especially in the region of what today is Bangladesh.[3] It was imported into Europe for much of the 17th and early 18th-centuries.[3]

In 2013, the traditional art of weaving Jamdani muslin in Bangladesh was included in the list of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.[6]

Also in late 2020 it gets recognition of Geographical indication as a product of Bangladesh by the effort of the Government of Bangladesh.[7] Muslin will be the fourth GI certified products after Jamdani saree, Hilsa fish and Khirsapat mango.

History

— Description of muslin by Amir Khusrau [8]

Earliest Muslin was known as Mulmul or Malmal which is an antiquated variety of Muslin. It was a handwoven fabric made with the finest handspun yarns.[9] [10][11]There were muslin qualities with 2425 thread count, which are questionable even with advanced technology. Some notable qualities of Muslin were Mulmul khas or Kings muslin,[12] Eksuti malmal,[13] and Alibal malmals, etc. The yarn count, weights and textures, thread count, origin, and particular use were the main criteria to differentiate them from each other. Muslin then was one of the legendary cloths of East India. These were made with localy grown cotton "Phuti karpas" a species of cotton with name Gossypium arboreum var. neglecta, The cotton was grown along side the river banks of Brahmaputra.Some notable varieties were as following. Muslin from eastern parts of ancient India was praised in the international market as woven wind ' and ' wonder gossamer, ' earned a great price.[14] [15][16]

The process of manufacturing

Since all the processes were manual, manufacturing involves many artisans for yarn spinning and weaving activities, but the leading role lies with the material and Weaving.

- Ginning: To removing trash and cleaning and combing the fibers and making them parallel ready for spinning a boalee (upper jaw of catfish) was used.

- Spinning and Weaving: For extra humidity they used to weave during the rainy season for elasticity in the yarns and to avoid breakages. The process was so sluggish that it could take over five months to weave one piece of mulmul.[17]

The muslins were originally made of cotton only. These were very thin, transparent, delicate and feather light breathable fabrics. There could be 1000-1800 yarns in warp and weighing 3.8 Ounces ( for 1yard X10 yards) . Some varieties of Muslin were so thin that they could even pass through the aperture of a lady finger-ring.[18][19][20]

In 1298 CE, Marco Polo described the cloth in his book The Travels. He said it was made in Mosul, Iraq.[21] The 16th-century English traveler Ralph Fitch lauded the muslin he saw in Sonargaon.[22] During the 17th and 18th centuries, Mughal Bengal emerged as the foremost muslin exporter in the world, with Mughal Dhaka as capital of the worldwide muslin trade.[23][24] It became highly popular in 18th-century France and eventually spread across much of the Western world.

Types

— Ralph Fitch a consultant for the British East India Company [25]

As per mentions in Ain-i-Akbari (16th-century detailed document) the Khasa[26] , Tansukh,[27] [28]Nainsook, Chautar,[29] [30]and varieties of mulmul (Sarkar ali, Sarbati, Tarindam)[31] were among the most delicate cotton muslins produced in the Indian subcontinent.[32][33][34]

Extinction

Under British rule, the British East India company could not compete with local muslin with their own export of cloth to the Indian subcontinent. The colonial government favored imports of British textiles. Colonial authorities attempted to suppress the local weaving culture. Muslin production greatly declined and the knowledge of weaving was nearly eradicated. It is alleged that in some instances the weavers were rounded up and their thumbs chopped off, although this has been refuted as an alleged misreading of a report from 1772.[35][36][37][38] The Bengali muslin industry was suppressed by various colonial policies.[39] As a result, the quality of muslin suffered and the finesse of the cloth was lost as British cloths emerged in India.

Uses

Dress-making and sewing

When sewing clothing, a dressmaker may test the fit of a garment, using an inexpensive muslin fabric before cutting pieces from expensive fabric, thereby avoiding potential costly mistakes. This garment is often called a "muslin," and the process is called "making a muslin." In this context, "muslin" has become the generic term for a test or fitting garment, regardless of what it is made from. The equivalent term in British English is Toile.

Muslin is also often used as a backing or lining for quilts, and thus can often be found in wide widths in the quilting sections of fabric stores.

In Asia, Muslin is used for making sarees. Bengali or Dhakai Muslin Saree is popular in Asia.

Shellac polishing

Muslin is used as a French polishing pad.

Culinary

Muslin can be used as a filter:

- In a funnel when decanting fine wine or port to prevent sediment from entering the decanter

- To separate liquid from mush (for example, to make apple juice: wash, chop, boil, mash, then filter by pouring the mush into a muslin bag suspended over a jug)

- To retain a liquidy solid (for example, in home cheese-making, when the milk has curdled to a gel, pour into a muslin bag and squash between two saucers (upside down under a brick) to squeeze out the liquid whey from the cheese curd)

Muslin is the material for the traditional cloth wrapped around a Christmas pudding.

Muslin is the fabric wrapped around the items in barmbrack, a fruitcake traditionally eaten at Halloween in Ireland.

Muslin is used when making traditional Fijian Kava as a filter.

Beekeepers use muslin to filter melted beeswax to clean it of particles and debris.

Theatre and photography

Muslin is often the cloth of choice for theatre sets. It is used to mask the background of sets and to establish the mood or feel of different scenes. It receives paint well and, if treated properly, can be made translucent.

It also holds dyes well. It is often used to create nighttime scenes because when dyed, it often gets a wavy look with the color varying slightly, such that it resembles a night sky. Muslin shrinks after it is painted or sprayed with water, which is desirable in some common techniques such as soft-covered flats.

In video production as well, muslin is used as a cheap greenscreen or bluescreen, either pre-colored or painted with latex paint (diluted with water). It is commonly used as a background for the chroma key technique.

Muslin is the most common backdrop material used by photographers for formal portrait backgrounds. These backdrops are usually painted, most often with an abstract mottled pattern.

In the early days of silent film-making, and up until the late 1910s, movie studios did not have the elaborate lights needed to illuminate indoor sets, so most interior scenes were sets built outdoors with large pieces of muslin hanging overhead to diffuse sunlight.

Medicine

Surgeons use muslin gauze in cerebrovascular neurosurgery to wrap around aneurysms or intracranial vessels at risk for bleeding.[40] The thought is that the gauze reinforces the artery and helps prevent rupture. It is often used for aneurysms that, due to their size or shape, cannot be microsurgically clipped or coiled.[41]

Early aviation

The Wright Brothers, in search of a light and strong covering for their gliders and the 1903 Wright Flyer (the first heavier-than-air powered aircraft), selected Pride of the West muslin as a covering for wings and control surfaces. A large piece of the fabric used on the original Wright Flyer (1903) was passed down to Wright descendants. The fabric was made available to The Wright Experience[42] (reproduction of the Wright gliders and Flyer and reenactment of the first flight on its 100th anniversary) for examination as it was no longer commercially available a century after its use by the Wrights. To create an authentic modern reproduction of the original fabric, three different companies were needed which produced the thread, the weaving, and the finishing.

See also

Notes

- muslin (noun), Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, March 2003

- muslin (noun), Webster's Unabridged Dictionary

- muslin, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- The Fairchild Books Dictionary of Textiles, A&C Black, 2013, pp. 404–, ISBN 978-1-60901-535-0

- muslin (noun), etymology, Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, March 2003

- "Jamdani recognised as intangible cultural heritage by Unesco". the daily star. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- "Muslin belongs to Bangladesh". Prothom Alo. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ''a piece of cloth the texture of which was so fine that the body was visible through it . One could fold a whole piece of this cloth inside one's nail ; yet it was large enough to cover the world when unfolded .'' Page 108 Life and Conditions of the People of Hindustan, 1200-1550 ...books.google.co.in › books Kunwar Muhammad Ashraf · 1978

- Lewandowski, Elizabeth J. (24 October 2011). The Complete Costume Dictionary. Scarecrow Press. pp. 198, 441. ISBN 978-0-8108-7785-6.

- Rohatgi, Sushila (1988). Musings. Pradeep Publications. p. 84.

- Tripathy, Rasananda (1986). Crafts and Commerce in Orissa in the Sixteenth-seventeenth Centuries. Mittal Publications. p. 141.

- Watson, J. Forbes (John Forbes); India Museum; Great Britain. India Office, publisher; Eyre & Spottiswoode, printer (1866). The textile manufactures and the costumes of the people of India. Getty Research Institute.

- Baden-Powell, Baden Henry (1872). Hand-book of the Manufactures & Arts of the Punjab: With a Combined Glossary & Index of Vernacular Trades & Technical Terms ... Forming Vol. Ii to the "Hand-book of the Economic Products of the Punjab" Prepared Under the Orders of Government. Punjab printing Company. p. 2.

- Mukhopādhyāẏa, Trailokyanātha (1888). Art-manufactures of India: Specially Compiled for the Glasgow International Exhibition, 1888. Superintendant of Government Printing.

- India Perspectives. Produced by PTI for the Ministry of External Affairs. 1998. p. 33.

- "mulmul", The Free Dictionary, retrieved 26 November 2020

- Ashmore, Sonia (1 October 2018). "Handcraft as luxury in Bangladesh: Weaving jamdani in the twenty-first century". International Journal of Fashion Studies. 5 (2): 389–397. doi:10.1386/infs.5.2.389_7.

- Watson, John Forbes (1867). The Textile Manufactures and the Costumes of the People of India. Allen. p. 75.

- Balfour, Edward (1885). The Cyclopædia of India and of Eastern and Southern Asia, Commercial Industrial, and Scientific: Products of the Mineral, Vegetable, and Animal Kingdoms, Useful Arts and Manufactures. Bernard Quaritch. p. 830.

- Indian Journal of Economics. University of Allahabad, Department of Economics. 1998. p. 435.

- Polo, Marco. The most noble and famous travels of Marco Polo, together with the travels of Nicoláo de' Conti. Translated by John Frampton, London, A. and C. Black, 1937, p.28.

- Shamim, Shahid Hussain; Selim, Lala Rukh (2007), "Handloom Textiles", in Selim, Lala Rukh (ed.), Art and Crafts, Cultural survey of Bangladesh series, Volume 8, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh, p. 552, OCLC 299379796

- Eaton, Richard Maxwell (1996), The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760, University of California Press, p. 202, ISBN 978-0-520-20507-9

- Karim, Abdul (2012), "Muslin", in Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh

- Eaton, Richard M. (31 July 1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20507-9.

- Museum, Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II; Museum, Maharaja of Jaipur (1979). Textiles and Costumes from the Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum. Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum Trust. pp. XII.

- Khadi Gramodyog. Khadi & Village Industries Commission. 2001. p. 88.

- Congress, Indian History (1967). Proceedings. Indian History Congress. p. 243.

- Burnell, Arthur Coke (15 May 2017). The Voyage of John Huyghen van Linschoten to the East Indies: From the Old English Translation of 1598. The First Book, containing his Description of the East. In Two Volumes Volume I. Taylor & Francis. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-317-01231-3.

- Sangar, Pramod (1993). Growth of the English Trade Under the Mughals. ABS Publications. p. 171. ISBN 978-81-7072-044-7.

- Sinha, Narendra Krishna (1961). The Economic History of Bengal from Plassey to the Permanent Settlement. Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay. p. 177.

- ''Cotton clothes: 1. Khasa per piece (than) - 3 rupiya to 15 muhr 2. Chautar per piece - 2 rupiya to 9 muhr 3. Malmal per piece - 4 rupiya 4. Tansukh per piece - 4 rupiya to 5 muhr'' Page 87 https://ir.nbu.ac.in/bitstream/123456789/2751/13/13_chapter%205.pdf

- Chaudhury, Sushil (10 March 2020). Spinning Yarns: Bengal Textile Industry in the Backdrop of John Taylor’s Report on ‘Dacca Cloth Production’ (1801). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-07920-3.

- Bhattacharya, Ranjit Kumar; Chakrabarti, S. B. (2002). Indian Artisans: Social Institutions and Cultural Values. Anthropological Survey of India, Government of India, Ministry of Culture, Youth Affairs and Sports, Department of Culture. p. 87. ISBN 978-81-85579-56-6.

- Bolts, William (1772), Considerations on India affairs, J Almon, p. 194

- Edwards, Michael (June 1976), Growth of the British Cotton Trade 1780–1815, Augustus M Kelley Pubs, p. 37, ISBN 0-678-06775-9

- Marshall, P. J. (1988), India and Indonesia during the Ancien Regime, E.J. Brill, p. 90, ISBN 978-90-04-08365-3

- Samuel, T. John (2013), Many avatars : challenges, achievements and the future, [S.l.]: Friesenpress, ISBN 978-1-4602-2893-7

- Bolts, William (1772), Considerations on India affairs: particularly respecting the present state of Bengal and its dependencies, Printed for J. Almon, pp. 194–195

- Pool, J. (1976), "Muslin gauze in intracranial vascular surgery. Technical note.", Journal of Neurosurgery, 44 (1): 127–128, doi:10.3171/jns.1976.44.1.0127, PMID 1244428

- Berger, C.; Hartmann, M.; Wildemann, B. (March 2003), "Progressive visual loss due to a muslinoma – report of a case and review of the literature", European Journal of Neurology, 10 (2): 153–158, doi:10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00546.x, PMID 12603290, S2CID 883414

- The Wright Experience

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Muslin. |

References

- Asher, Catherine B.; Talbot, Cynthia (2006), India Before Europe, Cambridge University Press, pp. 281–, ISBN 978-0-521-80904-7

- Eaton, Richard M. (1996), The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760, University of California Press, pp. 202–, ISBN 978-0-520-20507-9

- Islam, Khademul. 2016. Our Story of Dhaka Muslin. AramcoWorld. Volume 67 (3). May/June 2016. Pages 26–32. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/895830331.

- Prakash, Om (1998), European Commercial Enterprise in Pre-Colonial India, Cambridge University Press, pp. 202–, ISBN 978-0-521-25758-9

- Riello, Giorgio; Parthasarathi, Prasannan, eds. (2011), The Spinning World: A Global History of Cotton Textiles, 1200-1850, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-969616-1

- Riello, Giorgio; Roy, Tirthankar, eds. (2009), How India Clothed the World: The World of South Asian Textiles, 1500-1850, BRILL, pp. 219–, ISBN 978-90-04-17653-9

- Staples, Kathleen A.; Shaw, Madelyn C. (2013), Clothing Through American History: The British Colonial Era, ABC-CLIO, pp. 96–, ISBN 978-0-313-08460-7

| Look up muslin in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

.svg.png.webp)

'.jpg.webp)