Effigy mound

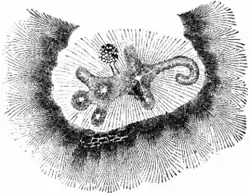

An effigy mound is a raised pile of earth built in the shape of a stylized animal, symbol, religious figure, human, or other figure. Effigy mounds were primarily built during the Late Woodland Period (350-1300 CE).

.jpg.webp)

Effigy mounds were constructed in many Native American cultures. Scholars believe they were primarily for religious purposes, although some also fulfilled a burial mound function. The builders of the effigy mounds are usually referred to as the Mound Builders. Native American societies in Wisconsin built more effigy mounds than did those in any other region of North America—between 15,000 and 20,000 mounds, at least 4,000 of which remain today.

Native North American effigy mounds have been compared to the large-scale geoglyphs such as the Nazca Lines of Peru.

History

Early European observations

Effigy mounds are limited to the Northern and Eastern United States, and most likely the French were the first Europeans to see them in their expeditions southward from Canada after 1673.

Early surveyors and settlers noticed and mapped many effigy mounds, but farming and other development erased numerous sites despite efforts to preserve them.

Mythology

After the "discovery" of effigy mounds, and other mounds all over the country, wild theories began to be developed as to how and by whom they were built. The first theories were the most accurate; people in the late 17th century assumed that the mounds had been built by the Native American people who still lived in the vicinity. These logical assumptions lost popularity as more fantastic theories were developed. The most popular of these theories in the 19th century was that an extinct race of Mound Builder people had built the mounds and then vanished. This theory was laid to rest by archaeologists at the Smithsonian Institution in the 1880s.

Origin theories

The Ho-Chunk suggest that effigy mounds were used as places of refuge as well as burial. Some archaeologists today believe that the mounds were built by particular clans or groups to honor their representative animal. Some believe that the animal shape is the clan or extended family of the person or person's buried in the mound. Others believe that the mounds were burial sites for everyday people, while still others believe that the depicted animal might be somehow responsible for transitioning the deceased into the next world. The mounds may also indicate hunting and gathering territories of different groups. Other evidence suggests that effigy mounds were used for all manner of rites and ceremonies, from birth ceremonies to funeral rites.

Appearance

Common shapes

Common shapes for effigy mounds include birds, bear, deer, bison, lynx, panther, turtles, and water spirits. These are somewhat arbitrary names given to the mound shapes by archaeologists who were simply looking for words that would help them classify the mounds. These shapes were most likely chosen for their particular religious or spiritual significance. The earliest mounds are 'conical'; they are essentially bumps of earth - the simplest and arguably the most intuitive kind of burial. Successive conicals likely evolved into linear mounds. Bird mounds likely came next as modifying a linear mound to make a bird mound required only the addition of a head and a tail. From there many different animal forms emerged. These often expressed a kind of abstract elongation.

Aesthetics

In addition to the obvious elongation of tails and the abstracted nature of many of the shapes, colored silts and sand were often used to decorate the mounds. The land was often scraped or raked to move earth from surface soils towards a new mound and in doing so, artful colored sand and silt patterning was sometimes employed as adornment. In terms of positioning, some mounds may have had celestial alignments although with certainty bird mounds were placed in such a way as to suggest that they were flying up or down a hillside, and animal mounds were often placed so as to suggest animals walking along natural landform as well such as a ridge or hillside. It is possible that predominant wind patterns may have been taken into consideration when choosing locations and orientations for bird mounds. In addition bird mounds sometimes appear in different conformations where the wings of the bird may be folded or unfolded to different degrees, suggesting various postures in flying. There are some instances where these different poses may suggest a freeze frame view of a bird flying - wings outstretched, wings partially folded, and wings outstretched again.

Hochunk ancestors naturally buried their dead next to lakes and rivers, and on hillsides. These locations would later become valued as some of the best places to live by settlers. This is one factor that contributed to high rates of mound destruction. Many mounds were destroyed by people grading earth surrounding their houses or what would become the foundations of houses. In some cases linear mounds were used as foundational fill for new house construction. Looting of mounds by settlers was common and this also contributed to the destruction and defacement of many.[1]

Locations

According to the National Park Service, the area in which effigy mounds are found "extends from Dubuque, Iowa, north into southeast Minnesota, across southern Wisconsin from the Mississippi to Lake Michigan, and along the Wisconsin–Illinois boundary."[2]

Contents

The Effigy Mound Builders buried one, two, or three people in a single mound. These burials were most often done singly – one atop the other in successive years. The effigy mound builders did not include with their dead the wealth of material the Ohio Hopewellians did. This almost complete lack of artifacts accompanying the dead clearly indicates a culture distinct from the Hopewellian, even though mounds with Hopewell-type grave goods have been excavated in the same area, and apparently were constructed at roughly the same time as the effigy mounds. Some have speculated that due to the lack of burial goods, that the effigy mound builders were egalitarian peoples.

Current condition

Preservation

Hundreds of effigy mounds have been lost due to plowing, farming, and other development. Many of the remaining effigy mound sites are parts of national, state, county, or municipal parks. All effigy mounds are currently protected under state laws that prohibit disturbance to burial sites or, if on federal or tribal land, the Archaeological Resources Protection Act, the Antiquities Act, and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

See also

- Adena culture

- Effigy Mounds National Monument

- Hopewell culture

- Indian Mounds Park (disambiguation) (15 sites)

- Lizard Mound County Park

- Rock Eagle Effigy Mound

- Rock Hawk Effigy Mound

- Serpent Mound

References

- "Brown, Charles E. "Undescribed Groups of Lake Mendota Mounds", Wisconsin Archaeologist, Vol 11 No. 1.

- National Park Service. "Effigy Moundbuilders," August 1, 2006. Accessed October 22, 2009.

Sources

- Birmingham, Robert. Spirits of Earth: The Effigy Mound Landscape of Madison and the Four Lakes. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2010.

- Birmingham, Robert, and Leslie Eisenberg. Indian Mounds of Wisconsin. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2000.

- Brown, Charles E. "Undescribed Groups of Lake Mendota Mounds." The Wisconsin Archaeologist 11.1 (1912-1913), 7-33.

- Highsmith, Hugh. The Mounds of Koshkonong and Rock River: A History of Ancient Indian Earthworks in Wisconsin. Fort Atkinson, WI: Fort Atkinson Historical Society and Highsmith Press, 1997.

- Kavasch, E. Barrie. The Mound Builders of Ancient North America. Lincoln, NE: iUniverse, 2004.

- McKern, W.C. "Regarding the Origin of Wisconsin Effigy Mounds." American Anthropologist 31.3 (1929), 562-564.

- Peet, Stephen Denison. '"Emblematic Mounds and Animal Effigies." Prehistoric America, Vol. II. Antiquarian Library, American Antiquarian Office, Chicago, Ill., 1890.

- Silverberg, Robert. The Mound Builders of Ancient America. Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society, 1968. 1986 abridged edition

- Smith, Watson (1969). "Review of Mound Builders of Ancient America: The Archaeology of a Myth by Robert Silverberg". American Antiquity. 34 (2): 184. doi:10.2307/278051. ISSN 0002-7316.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Effigy mounds. |

- Effigy Mounds Culture Wisconsin Historical Society

- Effigy Moundbuilders Effigy Mounds National Monument (U.S. National Park Service)