Pueblo Bonito

Pueblo Bonito (Spanish for beautiful town) is the largest and best-known great house in Chaco Culture National Historical Park, northern New Mexico. It was built by the Ancestral Puebloans who occupied the structure between AD 828 and 1126.

| Pueblo Bonito | |

|---|---|

Aerial view, from the south | |

Site map | |

| Location | San Juan County, New Mexico, |

| Coordinates | 36°03′39″N 107°57′42″W |

| First occupied | 828 |

| Built by | Chacoan civilization |

| Abandoned | 1126 |

| Governing body | Private |

Located in present-day New Mexico | |

According to the National Park Service, "Pueblo Bonito is the most thoroughly investigated and celebrated cultural site in Chaco Canyon. Planned and constructed in stages between AD 850 to AD 1150 by ancestral Puebloan peoples, this was the center of the Chacoan world."[1] Anthropologist Brian Fagan has said that "Pueblo Bonito is an archeological icon, as famous as England's Stonehenge, Mexico's Teotihuacan, or Peru's Machu Picchu."[2]

In January 1941, a section of the canyon wall known as Threatening Rock, or tse biyaa anii'ahi (leaning rock gap) in Navajo, collapsed as a result of a rock fall, destroying some of the structure's rear wall and a number of rooms. The builders of Pueblo Bonito appear to have been well aware of this threat, but chose to build beneath the fractured stone anyway. The wall stood 97 feet (30 m) high and weighed approximately 30,000 tons; the Puebloans compensated by building structural reinforcements for the slab.

In 2009, traces of Mexican cacao from at least 1,200 miles (1,900 km) away were detected in pottery sherds at Pueblo Bonito. This was the first demonstration that the substance, important in rituals, had been brought into the area that became the United States at any time before the Spanish arrived around 1500. Cylindrical pottery jars, common in Central America, had previously been found there, but are rare. 111 jars have been found in Pueblo Bonito's 800 or so rooms.[3]

Discovery

United States army Lt. James H. Simpson and his guide, Carravahal, from San Ysidro, New Mexico, discovered Chaco Canyon during an 1849 military expedition.[4] They briefly examined eight large ruins in Chaco Canyon, and Carravahal gave them their Spanish names, including Pueblo Bonito, meaning beautiful village.[5] Simpson later published the first description of Chaco Canyon in his military report, with drawings by expedition artist R. H. Kern.[6]

Rancher Richard Wetherill and natural history student George H. Pepper from the American Museum of Natural History, began excavations at Pueblo Bonito in 1896 and ended in 1900. These excavations were financed by B. Talbot Hyde and Frederick E. Hyde, Jr. of New York City, who were philanthropists and collectors. During this time, the two men uncovered 190 rooms and photographed and mapped all major structures in the canyon.

Among the artifacts recovered by Pepper, eight wood flutes were found in a room in the northwestern part of Pueblo Bonito that Pepper designated as "Room 33". These flutes are in the style of the Anasazi flutes that are considered a predecessor to the Native American flute.[7][8] The rituals at Pueblo Bonito were performed with cylindrical vessels, human effigy vessels, and ceramic incense burners.[9] The Hydes donated the resulting large collection of artifacts to the American Museum of Natural History. After the excavation, Wetherill sought to gain personal control of parts of Chaco Canyon, including Pueblo Bonito, Chetro Ketl, and Pueblo Del Arroyo. He filed a homestead entry on these ruins, which was invalidated by the General Land Office in 1904 when the federal government took formal possession of these lands. Wetherill was required to stop his ongoing excavations on federal property, but continued to run a trading post at Chaco Canyon until his death in 1910.

Description

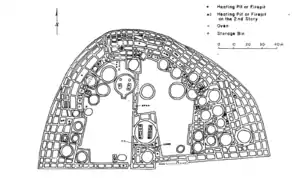

Pueblo Bonito is divided into two sections by a precisely aligned wall which runs north to south through the central plaza. A Great Kiva is situated on either side of the wall, creating a symmetrical pattern common to many of the Great Houses. In addition to the Great Kivas, over thirty other kivas or ceremonial structures have been found, many also associated with the large central courtyard. Interior living spaces were quite large by the standards of the Ancient Pueblo.

The site covers 3 acres (1.2 ha) and incorporates approximately 800 rooms.[10] In parts of the village, the tiered structure was four and five stories high. During later construction, some lower level rooms were filled with debris to better support the weight of the upper levels. The builder's use of core-and-veneer architecture and multi-story construction produced massive masonry walls as much as 3 feet (0.91 m) thick.

Population estimates for the village vary. During the early 20th century, the structures were viewed as small cities, with people residing in every room. From this perspective, Pueblo Bonito could have accommodated several thousand inhabitants at its peak. Recent analysis has lowered the estimated population to less than 800, primarily due to the small number of usable hearths in the ruins. An analysis based on architecture estimated the resident population at 12 households, or about 70 people at its peak.[11] These tend to be located on the ground floor, near the central plaza, and are associated with entrances to a series of rooms going deeper into the structure. Rooms were connected by a series of interior doorways, some of them in a T-shape. A family may have inhabited 3 to 4 rooms, with many small interior spaces being used for storage. There was generally no outside access to the room blocks other than from the central courtyard.

It is possible that Pueblo Bonito is actually neither a village nor city. While its size has the capacity for a significant population, the environment may not have been ideal for sustaining a large population. Excavations at the site have not revealed significant trash middens indicating residential areas. A common suggestion is that Pueblo Bonito was a ritual center. This is evident in not only the existence of the kivas (which are more often than not attributed to ritual function) but also the construction of the site and its relation to other Chaco Canyon sites. Although there were many occupants, only 50-60 burials were found here.[9]

The site indicates the Puebloans' comprehension of solar and lunar cycles; both of which are marked in the petroglyphs of the surrounding cliff area as well as in the architecture of Pueblo Bonito itself.

Examination of pack rat middens revealed that at the time that Pueblo Bonito was built, Chaco Canyon and the surrounding areas were wooded by trees such as ponderosa pines. Evidence of such trees can be seen within the structure of Pueblo Bonito, such as the first-floor support beams. Scientists hypothesized that during the time when the pueblo was inhabited, the valley was cleared of almost all of the trees, to provide timber for construction and fuel. This tree removal, combined with a period of drought, led the water table in the valley to drop severely, making the land infertile. This explains why Pueblo Bonito was inhabited for only about 300 years and is a good example of the effect that deforestation can have on the local environment. The Anasazi, no longer able to grow crops to sustain their population, had to move on.

Beginning in 2004, the University of New Mexico started a campaign to reopen excavations of the great house in order to obtain new data. Major excavations of Chaco Canyon occurred during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; for this reason, the nature of the incredible social transformation that developed in Chaco Canyon and its underlying causes remains poorly understood.

A multi-year field study, centered in Pueblo Bonito, was launched to gather new information on the economic conditions of the Bonito phase. The ultimate goal of this recent fieldwork is to obtain data that will enable researchers to examine the development of great-house communities in respect to relationships between demographic change and economic productivity.

Thus far, the team from the University of New Mexico has recovered and inventoried thousands of artifacts, including ceramics, animal bones, and stone fragments. As a result, the researchers have received a separate grant from the National Science Foundation to analyze more than 300,000 artifacts: the largest single-site artifact assemblage ever collected from Chaco.

Matriliny

Room 33 is one of the most well-excavated areas of Pueblo Bonito and belongs to the earliest construction phase of the site in the 9th century. A concentration of elite burials occurred in room 33, which are differentiated from other burials in Chaco Canyon since most people were buried outside the great houses.[12] The oldest burial was of a man who died violently, and archaeologists believe that room 33 was built as a crypt for him and his descendants.[13] He was buried with thousands of turquoise and shell beads and pendants, which originally formed necklaces, anklets and bracelets, making his the richest burial ever excavated in the Southwest.[14][15][13] Over the next 330 years, thirteen other individuals (both men and women) were buried in the same crypt with many elite grave goods suggesting important ritual functions in the community. Archaeogenomic analysis found that nine of these individuals shared mitochondrial DNA, meaning they were all related through the female line. Archaeologists have concluded that Pueblo Bonito was associated with an elite matriline, a powerful family who inherited their status from their mothers, for approximately 330 years. The room 33 excavations are the first archaeological evidence of matrilineal descent among the Ancestral Puebloans, which is a further link to their modern Pueblo descendants, many of whom practice matrilineal succession.[13]

Construction

The archeologist Mary Metcalf estimates that 805,000 man-hours were required to build Pueblo Bonito's main structure.[16]

Rock art

On the rock wall directly behind Pueblo Bonito is a series of petroglyphs depicting six-toed feet, a stylistic element also found in other Ancient Pueblo rock art. These images date to the late 10th or early 11th centuries.[17]

References

- National Park Service.

- Fagan 2005, p. 117.

- Thomas H. Maugh II (February 3, 2009). "Earlier traces of cacao use found in Southwest". Los Angeles Times.

- Reed 2004, pp. 16, 106.

- Reed 2004, pp. 16–7.

- Reed 2004, pp. 116–7.

- Clint Goss (2012). "The Development of Flutes in North American: The Pueblo Bonito and other Mojave Flutes". Flutopedia. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- Clint Goss (2012). "The Flutes of Pueblo Bonito". Flutopedia. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- Snow 2010, p. 131.

- Judd 1957, p. 561.

- Bernardini, Wesley (1999). "Reassessing the scale of social action at Pueblo Bonito, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico". Kiva, the Journal of Southwest Anthropology and History. 64 (4): 447–470.

- Plog, S.; Heitman, C. (November 8, 2010). "Hierarchy and social inequality in the American Southwest, A.D. 800-1200". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (46): 19619–19626. doi:10.1073/pnas.1014985107. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2993351. PMID 21059921.

- Perry, George H.; Reich, David; Whiteley, Peter M.; LeBlanc, Steven A.; Kistler, Logan; Stewardson, Kristin; Swapan Mallick; Rohland, Nadin; Skoglund, Pontus (February 21, 2017). "Archaeogenomic evidence reveals prehistoric matrilineal dynasty". Nature Communications. 8: 14115. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814115K. doi:10.1038/ncomms14115. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5321759. PMID 28221340.

- Hodge, Frederick Webb; Leary, Ella (1916). Holmes anniversary volume; anthropological essays presented to William Henry Holmes in honor of his seventieth birthday, December 1, 1916. Washington: [Printed at the J.W. Bryan press]. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.61163. hdl:2027/umn.31951p00853855t.

- Pepper, G. H. Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History Vol. XXVII, (New York, (1920).

- Fagan 2005, p. 143.

- University of Colorado Boulder.

Bibliography

- Fagan, Brian (2005). Chaco Canyon: Archaeologists Explore the Lives of an Ancient Society. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195170436.

- Judd, Neil M. (July 27, 1957). "The Architectural Evolution of Pueblo Bonito". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. National Academy of Sciences. 13 (7): 561–563. doi:10.1073/pnas.13.7.561. PMC 1085076. PMID 16587221.

- Judd, Neil M.; Allen, Glover M. (1954). The Material Culture of Pueblo Bonito: Reprints in Anthropology. 23. J. & L. Reprint Company. ASIN B00AXBGXNO.

- National Park Service. "Chaco Culture: Pueblo Bonito". US Government. Retrieved March 3, 2015.

- Neitzel, Jill E., ed. (2003). Pueblo Bonito: Center of the Chacoan World. Smithsonian Books. ISBN 978-1588341310.

- Reed, Paul F. (2004). The Puebloan Society of Chaco Canyon. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313327209.

- Snow, Dean R. (2010). Archaeology of Native North America. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 9780136156864.

- University of Colorado Boulder. "Pueblo Bonito". Archived from the original on June 3, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2015.

- Vivian, R. Gwinn; Hilpert, Bruce (2012). Chaco Handbook: An Encyclopedia Guide (2 ed.). University of Utah Press. ISBN 978-1607811954.

Further reading

- Heitman, Carrie C.; Plog, Steve, eds. (2015). Chaco Revisited: New Research on the Prehistory of Chaco Canyon, New Mexico. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0816531608.

- Nobel, David Grant, ed. (2004). In Search of Chaco: New Approaches to an Archaeological Enigma. School of American Research Press. ISBN 978-1930618428.

- Simpson, James H. (2003). McNitt, Frank (ed.). Navajo Expedition: Journal of a Military Reconnaissance from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to the Navaho Country, Made in 1849. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806135700.

- Snow, Dean R. (2010). Archaeology of Native North America. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 9780136156864.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pueblo Bonito. |

- The Mystery of Chaco Canyon a PBS documentary narrated by Robert Redford

- Chaco Canyon, a Photo Gallery

- Pueblo Bonito: 1995 Site Guide

- New Research at Pueblo Bonito