Thunderbird (mythology)

The thunderbird is a legendary creature in certain North American indigenous peoples' history and culture. It is considered a supernatural being of power and strength. It is especially important, and frequently depicted, in the art, songs and oral histories of many Pacific Northwest Coast cultures, but is also found in various forms among some peoples of the American Southwest, East Coast of the United States, Great Lakes, and Great Plains.

| |

| Grouping | Legendary creature |

|---|---|

| Region | North America |

General description

The thunderbird is said to create thunder by flapping its wings (Algonqian,[1] ), and lightning by flashing its eyes (Algonquian, Iroquois.[2])

Algonquian

The thunderbird myth and motif is prevalent among Algonquian peoples in the "Northeast", i.e., Eastern Canada (Ontario, Quebec, and eastward) and Northeastern United States, and the Iroquois peoples (surrounding the Great Lakes).[3] The discussion of the "Northeast" region has included Algonquian-speaking people in the Lakes-bordering U.S. Midwest states (e.g., Ojibwe in Minnesota[4]).

In Algonquian mythology, the thunderbird controls the upper world while the underworld is controlled by the underwater panther or Great Horned Serpent. The thunderbird creates not just thunder (with its wing-flapping), but lightning bolts, which it cast at the underworld creatures.[1]

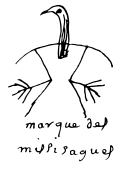

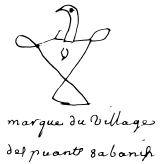

Thunderbirds in this tradition may be depicted as a spread-eagled bird (wings horizontal head in profile), but also quite commonly with the head facing forward, thus presenting an X-shaped appearance overall[4] (see under §Iconography below).

Ojibwe

The Ojibwe version of the myth states that the thunderbirds were created by Nanabozho for the purpose of fighting the underwater spirits. They were also used to punish humans who broke moral rules. The thunderbirds lived in the four directions and arrived with the other birds in the springtime. In the fall they migrated south after the ending of the underwater spirits' most dangerous season.[5]

Menominee

The Menominee of Northern Wisconsin tell of a great mountain that floats in the western sky on which dwell the thunderbirds. They control the rain and hail and delight in fighting and deeds of greatness. They are the enemies of the great horned snakes - the Misikinubik - and have prevented these from overrunning the earth and devouring mankind. They are messengers of the Great Sun himself.[6]

Siouan

The thunderbird motif is also seen in Siouan-speaking peoples, which include tribes traditionally occupying areas around the Great Lakes.

Iconography

X-shapes

In Alogonquian an X-shaped thunderbird is often used to depict the thunderbird with its wings alongside its body and the head facing forwards instead of in profile.[3]

The depiction may be stylized and simplified. A headless X-shaped thunderbird was found on an Ojibwe midewiwin disc dating to 1250–1400AD.[8] In an 18th century manuscript (a "daybook" ledger) written by the namesake grandson of Governor Matthew Mayhew the thunderbird pictograms varies from a "recognizable birds to simply an incised X".[9]

Scientific interpretation

The historians Adrienne Mayor and Tom Holland have suggested that thunderbird stories are based on discoveries of pterosaur fossils by Native Americans.[10][11]

In modern usage

- In 1925, Aleuts were recorded as using the term to describe the Douglas World Cruiser aircraft which passed through Atka on the first aerial circumnavigation by a US Army team the previous year.[12]:100

- In one of his speeches, which took place few days before the Iranian revolution, Shapour Bakhtiar, the last Prime Minister of Imperial Iran, said: "I am a thunderbird. I am not afraid of the storm".[lower-alpha 1] Due to this, Bakhtiar is known as the Thunderbird.[13]

See also

Explanatory notes

- A verse of "the Thunderbird" poem, by the Iranian poet "Radi Azarkhshi".

References

- Citations

- Cleland, Chute & Haltiner (1984), p. 240

- Lenik (2012), p. 163

- Lenik (2012), p. 163.

- Lenik (2012), p. 181.

- Vecsey, Christopher (1983). Traditional Ojibwa Religion and Its Historical Changes. 152. American Philosophical Society. p. 75. ISBN 9780871691521.

- Lankford, George E. (2011). Native American Legends of the Southeast: Tales from the Natchez, Caddo, Biloxi, Chickasaw, and other Nations. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. p. 77. ISBN 9780817356897.

- Burlin, Nathalie C. (1907). The Indians' Book: An Offering by the American Indians of Indian Lore, Musical and Narrative, to Form a Record of the Songs and Legends of Their Race. Harper and Brothers.

- Bouck & Richardson (2007), p. 15, citing Cleland (1984), p. 240, figure 2C; Lenik (1985), p. 132, figure 5.

- Bouck & Richardson (2007), p. 15.

- Fossil Legends of the First Americans

- BBC Four - Dinosaurs, Myths and Monsters

- Thomas, Lowell (1925). The First World Flight. Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- طنزپرداز, هادی خرسندی شاعر، نویسنده و. "بختیار؛ او مرغ طوفان بود و ما طوطی ایوان". BBC News فارسی (in Persian). Retrieved 2019-10-12.

- Bibliography

- Bouck, Jill; Richardson, James B., III (2007). "Enduring Icon: A Wampanoag Thunderbird on an Eighteenth Century English Manuscript From Martha's Vineyard". Archaeology of Eastern North America. 35: 11–19. JSTOR 40914506.

External links

![]() Media related to Thunderbird (mythology) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Thunderbird (mythology) at Wikimedia Commons

.svg.png.webp)