Elfern

Elfern, also known as Eilfern, Figurenspiel or Elfmandeln, is a very old, German and Austrian 6-card, no-trump, trick-and-draw game for two players using a 32-card, French-suited Piquet pack or German-suited Skat pack. The object is to win the majority of the 20 honours: the Ace, King, Queen, Jack and Ten in a Piquet pack or the Ace, King, Ober, Unter and Ten in a Skat pack. Elfern is at least 250 years old and a possible ancestor to the Marriage family of card games, yet it is still played by German children.[2][3]

| "An old game that's very easy and enjoyable"[1] | |

The 'honours' in the suit of Leaves. | |

| Origin | Germany |

|---|---|

| Type | Point-trick |

| Players | 2 |

| Cards | 32 |

| Deck | German or French |

| Play | Alternate |

| Card rank (highest first) | A K Q J 10 9 8 7 or A K O U 10 9 8 7 |

| Related games | |

| Bohemian Schneider | |

History and Etymology

Elfern is a primitive German game, similar to Bohemian Schneider, that is mentioned as early as 1759 in a letter by Christian Fürchtegott Gellert;[2] its rules appearing in Hammer's Taschenbuch in 1811[4] and in the Neuester Spielalmanach published in Berlin in 1820.[5] It was described in 1855 as "played in many parts of Germany, albeit not very commonly"[6] and, in 1862, as "the simplest drinking game", the winner of the majority of honours, earning the "right of drinking from the glasses of his opponents."[7][8] Although Parlett states that the game was "not recorded before the nineteenth century", he suggests that its non-trump nature points to its being much older and possibly ancestral to Marriage family of card games. It is still played by German children.[3]

Elfern, formerly also called Eilfern, is German for "playing Elevens", and Elfmandeln is Austrian and Bavarian German for "eleven little men". Thus both names refer to the score of 11 points required for winning. Figurenspiel is also German and can be roughly translated as "honours game". This name evidently refers to the fact that only the court cards plus aces and tens contribute to the score.[3]

Cards

From the earliest days both "the usual Piquet pack" of 32 cards was used or the game was played with German-suited cards. Cards rank in their natural order: A > K > Q > J > 10 > 9 > 8 > 7 and there are no trumps. In 1835 Pierer states that Elfern or Eilfern is a card game played with German-suited cards. In this case they rank D > K > O > U > 10 > 9 > 8 > 7 where D is the Deuce, O is the Ober and U is the Unter.[9]

Rules

| Rank | A | K | Q/O | J/U | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 1 | – | ||||||

The first dealer is chosen by lots; the player who draws the lower-ranking card dealing first. Both players are then dealt a hand of 6 cards in batches of 2. There are no trumps, and tens rank low in trick-play. Forehand leads to the first trick. A trick is won by the player of the highest card of the suit led. In the first phase of the game, the winner of a trick draws a card from the stock, followed by the other player, before leading to the next trick. Players need not follow suit in this phase.[5]

The second phase begins as soon as the stock is depleted. In the second phase, players use up their hand cards and must follow suit, as revoking can now be proved in all cases.[5]

Except for ranks 7–9, which are worthless, every card is worth one point for a total of 20. The deal is won with a score of 11 or more, won double (opponent is schneider, tailor) with a score of 15 or more, and won triple (opponent is schwarz, literally "black") with a score of 20.[5]

The winner becomes the dealer in the next game. If the game is tied with both players winning 10 points, this is called a Ständer (formerly Stender). No game points are awarded; instead the winner of the next game wins both, i.e. the win is doubled. There are two way of choosing the dealer for this second game: either the dealer remains the same or, more commonly, is decided by drawing lots (e.g. cards) as at the start. In case of a second tie, the next game does not count quadruple.[1][5][6]

Scoring

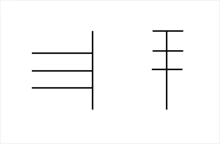

Various scoring systems have been used. Tendler describes one in which the winner receives one stake for a simple win, double if he wins schneider (15 points or more) and three times the basic stake if he wins schwarz (20 points). However, he goes on to say that, in practice, players usually record the scores in writing by chalking up one line for a simple win, two for schneider and 3 for schwarz. Four lines are drawn in the shape of a so-called flag or banner (Fahne, see illustration).[lower-alpha 1] The game ends when one player is first to score an agreed number of banners and the difference in scores is then settled by payment. This avoids the "boring toing and froing of payments for each deal won or lost".[10]

Gööck (1967) follows Tendler's scoring scheme,[11] however the Altenburg rule book (1988) introduces a more intricate, soft score system, as follows:[1]

- 20 honours - 5 points

- 18-19 honours - 4 points

- 16-17 honours - 3 points

- 14-15 honours - 2 points

- 11-13 honours - 1 point

Tactics

Von Abenstein advises players to pay close attention to the all-important honours in order to avoid throwing them away unnecessarily. At the start of the game try to lose all non-counters, keeping back one or two suits which your opponent cannot beat. Try to use these near the end of the game because, by then, most of the blanks have been discarded and you can now reckon on winning an honour with almost every trick.[5]

Try to avoid winning tricks when your opponent plays a non-counter, but as soon as an honour is played it is usually good to take it. However, there are times when this could do great damage and you may lose the game over it. For example. if you have an Ace and your opponent has a strong card in the same suit, you may increase his strength by playing your Ace too early without capturing an honour. Equally, if you have the Ace, Jack and Ten of a suit, you don't have to win the trick immediately your opponent plays the King because, if he also has the Queen, he is likely to play it next and now you can capture it and free up your Jack and Ten as trick-winners. A singleton Ten is a risk and should be played the first time your opponent plays a non-counter of the same suit, otherwise you are in danger of losing it.[5]

If you have two or more cards in sequence and the first wins an honour, you should continue to play in that suit. Even if your opponent takes it with a higher card, you may now have freed up your lower honours as unbeatable cards (Freiblätter). The closer the game approaches the end, the more you should try to gain and retain the lead, otherwise you may end up discarding honours to your opponent's unbeatable cards.[5]

Variations

Recorded variations include:

- Trump suit. After dealing the top card of the talon is turned as trumps. Once the talon is used up, players must follow suit or, if unable, trump.[12] In addition:

- Refined scoring schedule. 11–13 honours 1 point, 14–15 honours 2 points, 16–17 honours 3 points, 18–19 honours 4 points, 20 honour 5 points. [1]

- Fewer hand cards. The game may be played with hands of fewer than 6 cards,[5] but then it becomes harder for the player who is not leading to a trick to recapture the lead and they can easily lose good cards because they are unable to follow suit.[6]

Footnotes

- Tendler gives one illustration of the 'banner' and von Abenstein another; both are shown.

References

- _ 1988, pp. 107/108.

- Reynolds 1987, p. 287.

- Parlett 1991, p. 281.

- Hammer 1811, pp. 265-274.

- von Abenstein 1820, pp. 198-202.

- von Alvensleben 1853, pp. 212-215.

- Parlett 2008, p. 255.

- Lese-Stübchen 1862, p. 238.

- Pierer 1835, p. 647.

- Tendler 1830, p. 203.

- Gööck 1967, pp. 33/34.

- von Thalberg 1860, p. 137.

Literature

- _ (1862) Lese-Stübchen: Illustrirte Unterhaltungs-Blätter für Familie und Haus, Vol. 3. Brünn.

- _ (1988). Erweitertes Spielregelbüchlein aus Altenburg, 8th edn., Altenburger Spielkartenfabrik, Altenburg.

- Gööck, Roland (1967). Freude am Kartenspiel, Bertelsmann, Gütersloh.

- Hammer, Paul (1811). Taschenbuch der Kartenspiele, Weygandschen Buchhandlung, Leipzig.

- Müller, Reiner F. (1994). Die bekanntesten Kartenspiele. Neff, Berlin. ISBN 3-8118-5856-4

- Parlett, David (1990), The Oxford guide to card games: a historical survey, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-214165-1.

- Parlett, David (1991), A History of Card Games, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-282905-X.

- Parlett, David (2008), The Penguin Book of Card Games (3rd ed.), Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-14-103787-5.

- Pierer, Heinrich August (1835). Universal-Lexikon oder neuestes vollständiges encyclopädisches Wörterbuch, Volume 6, Credo-Eliwager. Pierer, Altenburg.

- Reynolds, John F. (1987). C.F. Gellerts Briefwechsel, Vol. 2 (1756-1759). de Gruyter, Berlin/New York.

- Tendler, F. (1830). Verstand und Glück im Bunde. Ein theoretisch-practisches Spielbuch aller bis jetzt bekannten, älteren und neuesten, ihrer Solidarität wegen beliebten und erlaubten Kartenunterhaltungen... F. J. P. Sollinger, Vienna.

- von Abenstein, G.W. (1820) Neuester Spielalmanach für Karten-, Schach-, Brett-, Billard-, Kegel- und Ball-Spieler. Hann, Berlin.

- Von Alvensleben, L. (1853). Encyclopädie der Spiele: enthaltend alle bekannten Karten-, Bret-, Kegel-, Billard-, Ball-, Würfel-Spiele und Schach. Otto Wigand, Leipzig.

- von Thalberg, Baron F. (1860). Der perfecte Kartenspiele. S. Mode, Berlin.