Endangered language

An endangered language or moribund language is a language that is at risk of disappearing as its speakers die out or shift to speaking other languages. Language loss occurs when the language has no more native speakers and becomes a "dead language". If no one can speak the language at all, it becomes an "extinct language". A dead language may still be studied through recordings or writings, but it is still dead or extinct unless there are fluent speakers.[1] Although languages have always become extinct throughout human history, they are currently dying at an accelerated rate because of globalization, imperialism, neocolonialism[2] and linguicide (language killing).[3]

.jpg.webp)

Language shift most commonly occurs when speakers switch to a language associated with social or economic power or spoken more widely, the ultimate result being language death. The general consensus is that there are between 6,000[4] and 7,000 languages currently spoken and that between 50% and 90% of them will have become extinct by the year 2100.[2] The 20 most common languages, each with more than 50 million speakers, are spoken by 50% of the world's population, but most languages are spoken by fewer than 10,000 people.[2] On a more general level, 0.2% of the world's languages are spoken by half of the world's population. Furthermore, 96% of the world's languages are spoken by 4% of the population.

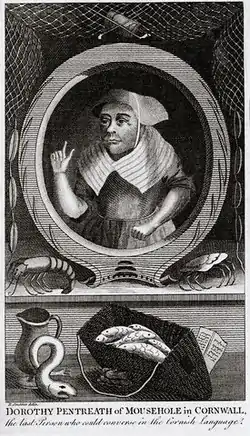

The first step towards language death is potential endangerment. This is when a language faces strong external pressure, but there are still communities of speakers who pass the language to their children. The second stage is endangerment. Once a language has reached the endangerment stage, there are only a few speakers left and children are, for the most part, not learning the language. The third stage of language extinction is seriously endangered. During this stage, a language is unlikely to survive another generation and will soon be extinct. The fourth stage is moribund, followed by the fifth stage extinction.

Many projects are under way aimed at preventing or slowing language loss by revitalizing endangered languages and promoting education and literacy in minority languages, often involving joint projects between language communities and linguists.[5] Across the world, many countries have enacted specific legislation aimed at protecting and stabilizing the language of indigenous speech communities. Recognizing that most of the world's endangered languages are unlikely to be revitalized, many linguists are also working on documenting the thousands of languages of the world about which little or nothing is known.

Number of languages

The total number of contemporary languages in the world is not known, and it is not well defined what constitutes a separate language as opposed to a dialect. Estimates vary depending on the extent and means of the research undertaken, and the definition of a distinct language and the current state of knowledge of remote and isolated language communities. The number of known languages varies over time as some of them become extinct and others are newly discovered. An accurate number of languages in the world was not yet known until the use of universal, systematic surveys in the later half of the twentieth century.[6] The majority of linguists in the early twentieth century refrained from making estimates. Before then, estimates were frequently the product of guesswork and very low.[7]

One of the most active research agencies is SIL International, which maintains a database, Ethnologue, kept up to date by the contributions of linguists globally.[8]

Ethnologue's 2005 count of languages in its database, excluding duplicates in different countries, was 6,912, of which 32.8% (2,269) were in Asia, and 30.3% (2,092) in Africa.[9] This contemporary tally must be regarded as a variable number within a range. Areas with a particularly large number of languages that are nearing extinction include: Eastern Siberia, Central Siberia, Northern Australia, Central America, and the Northwest Pacific Plateau. Other hotspots are Oklahoma and the Southern Cone of South America.

Endangered sign languages

Almost all of the study of language endangerment has been with spoken languages. A UNESCO study of endangered languages does not mention sign languages.[10] However, some sign languages are also endangered, such as Alipur Village Sign Language (AVSL) of India,[11] Adamorobe Sign Language of Ghana, Ban Khor Sign Language of Thailand, and Plains Indian Sign Language.[12][13] Many sign languages are used by small communities; small changes in their environment (such as contact with a larger sign language or dispersal of the deaf community) can lead to the endangerment and loss of their traditional sign language. Methods are being developed to assess the vitality of sign languages.[14]

Defining and measuring endangerment

While there is no definite threshold for identifying a language as endangered, UNESCO's 2003 document entitled Language vitality and endangerment[15] outlines nine factors for determining language vitality:

- Intergenerational language transmission

- Absolute number of speakers

- Proportion of speakers existing within the total (global) population

- Language use within existing contexts and domains

- Response to language use in new domains and media

- Availability of materials for language education and literacy

- Government and institutional language policies

- Community attitudes toward their language

- Amount and quality of documentation

Many languages, for example some in Indonesia, have tens of thousands of speakers but are endangered because children are no longer learning them, and speakers are shifting to using the national language (e.g. Indonesian) in place of local languages. In contrast, a language with only 500 speakers might be considered very much alive if it is the primary language of a community, and is the first (or only) spoken language of all children in that community.

Asserting that "Language diversity is essential to the human heritage", UNESCO's Ad Hoc Expert Group on Endangered Languages offers this definition of an endangered language: "... when its speakers cease to use it, use it in an increasingly reduced number of communicative domains, and cease to pass it on from one generation to the next. That is, there are no new speakers, adults or children."[15]

UNESCO operates with four levels of language endangerment between "safe" (not endangered) and "extinct" (no living speakers), based on intergenerational transfer: "vulnerable" (not spoken by children outside the home), "definitely endangered" (children not speaking), "severely endangered" (only spoken by the oldest generations), and "critically endangered" (spoken by few members of the oldest generation, often semi-speakers).[4] UNESCO's Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger categorises 2,473 languages by level of endangerment.[16] More than 200 languages have become extinct around the world over the last three generations.[17]

Using an alternative scheme of classification, linguist Michael E. Krauss defines languages as "safe" if it is considered that children will probably be speaking them in 100 years; "endangered" if children will probably not be speaking them in 100 years (approximately 60–80% of languages fall into this category) and "moribund" if children are not speaking them now.[18]

Many scholars have devised techniques for determining whether languages are endangered. One of the earliest is GIDS (Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale) proposed by Joshua Fishman in 1991.[19] In 2011 an entire issue of Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development was devoted to the study of ethnolinguistic vitality, Vol. 32.2, 2011, with several authors presenting their own tools for measuring language vitality. A number of other published works on measuring language vitality have been published, prepared by authors with varying situations and applications in mind.[20][21][22][23][24]

Causes

According to the Cambridge Handbook of Endangered Languages,[2] there are four main types of causes of language endangerment:

Causes that put the populations that speak the languages in physical danger, such as:

- War and genocide. Examples of this are the language(s) of the native population of Tasmania who died from diseases, and many extinct and endangered languages of the Americas where indigenous peoples have been subjected to genocidal violence. The Miskito language in Nicaragua and the Mayan languages of Guatemala have been affected by civil war.

- Natural disasters, famine, disease. Any natural disaster severe enough to wipe out an entire population of native language speakers has the capability of endangering a language. An example of this is the languages spoken by the people of the Andaman Islands, who were seriously affected by the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami.

Causes which prevent or discourage speakers from using a language, such as:

- Cultural, political, or economic marginalization creates a strong incentive for individuals to abandon their language (on behalf of themselves and their children as well) in favor of another more prestigious language; one example of this is assimilatory education. This frequently happens when indigenous populations and ethnic groups who were once subjected to colonisation and/or earlier conquest, in order to achieve a higher social status, have a better chance to get employment and/or acceptance in a given social network only when they adopt the cultural and linguistic traits of other groups with enough power imbalance to culturally integrate them, through various means of ingroup and outgroup coercion (see below); examples of this kind of endangerment are the cases of Welsh,[25] Scottish Gaelic, and Scots in Great Britain, Irish in Ireland and Great Britain, the Sardinian language in Italy,[26][27] the Ryukyuan and Ainu languages in Japan,[28] and the Chamorro language in Guam. This is also the most common cause of language endangerment.[2] Ever since the Indian government adopted Hindi as the official language of the union government, Hindi has taken over many languages in India.[29] Other forms of cultural imperialism include religion and technology; religious groups may hold the belief that the use of a certain language is immoral or require its followers to speak one language that is the approved language of the religion (like the Arabic language as the language of the Quran, with the pressure for many North African groups of Amazigh or Egyptian descent to Arabize[30]). There are also cases where cultural hegemony may often arise not from an earlier history of domination or conquest, but simply from increasing contact with larger and more influential communities through better communications, compared with the relative isolation of past centuries.

- Political repression. This has frequently happened when nation-states, as they work to promote a single national culture, limit the opportunities for using minority languages in the public sphere, schools, the media, and elsewhere, sometimes even prohibiting them altogether. Sometimes ethnic groups are forcibly resettled, or children may be removed to be schooled away from home, or otherwise have their chances of cultural and linguistic continuity disrupted. This has happened in the case of many Native American, Louisiana French and Australian languages, as well as European and Asian minority languages such as Breton, Occitan, or Alsatian in France and Kurdish in Turkey.

- Urbanization. The movement of people into urban areas can force people to learn the language of their new environment. Eventually, later generations will lose the ability to speak their native language, leading to endangerment. Once urbanization takes place, new families who live there will be under pressure to speak the lingua franca of the city.

- Intermarriage can also cause language endangerment, as there will always be pressure to speak one language to each other. This may lead to children only speaking the more common language spoken between the married couple.

Often multiple of these causes act at the same time. Poverty, disease and disasters often affect minority groups disproportionately, for example causing the dispersal of speaker populations and decreased survival rates for those who stay behind.

Marginalization and endangerment

Among the causes of language endangerment cultural, political and economic marginalization accounts for most of the world's language endangerment. Scholars distinguish between several types of marginalization: Economic dominance negatively affects minority languages when poverty leads people to migrate towards the cities or to other countries, thus dispersing the speakers. Cultural dominance occurs when literature and higher education is only accessible in the majority language. Political dominance occurs when education and political activity is carried out exclusively in a majority language.

Historically, in colonies, and elsewhere where speakers of different languages have come into contact, some languages have been considered superior to others: often one language has attained a dominant position in a country. Speakers of endangered languages may themselves come to associate their language with negative values such as poverty, illiteracy and social stigma, causing them to wish to adopt the dominant language which is associated with social and economical progress and modernity.[2] Immigrants moving into an area may lead to the endangerment of the autochthonous language.[31]

Effects

Language endangerment affects both the languages themselves and the people that speak them. Also, this effect the essence of a culture.

Effects on communities

As communities lose their language they often also lose parts of their cultural traditions which are tied to that language, such as songs, myths, poetry, local remedies, ecological and geological knowledge and language behaviors that are not easily translated.[32] Furthermore, the social structure of one's community is often reflected through speech and language behavior. This pattern is even more prominent in dialects. This may in turn affect the sense of identity of the individual and the community as a whole, producing a weakened social cohesion as their values and traditions are replaced with new ones. This is sometimes characterized as anomie. Losing a language may also have political consequences as some countries confer different political statuses or privileges on minority ethnic groups, often defining ethnicity in terms of language. That means that communities that lose their language may also lose political legitimacy as a community with special collective rights. Language can also be considered as scientific knowledge in topics such as medicine, philosophy, botany, and many more. It reflects a communities practices when dealing with the environment and each other. When a language is lost, this knowledge is lost as well.[33]

In contrast, language revitalization is correlated with better health outcomes in indigenous communities.[34]

Effects on languages

During language loss—sometimes referred to as obsolescence in the linguistic literature—the language that is being lost generally undergoes changes as speakers make their language more similar to the language that they are shifting to. For example, gradually losing grammatical or phonological complexities that are not found in the dominant language.[35][36]

Ethical considerations and attitudes

Generally the accelerated pace of language endangerment is considered to be a problem by linguists and by the speakers. However, some linguists, such as the phonetician Peter Ladefoged, have argued that language death is a natural part of the process of human cultural development, and that languages die because communities stop speaking them for their own reasons. Ladefoged argued that linguists should simply document and describe languages scientifically, but not seek to interfere with the processes of language loss.[37] A similar view has been argued at length by linguist Salikoko Mufwene, who sees the cycles of language death and emergence of new languages through creolization as a continuous ongoing process.[38][39][40]

A majority of linguists do consider that language loss is an ethical problem, as they consider that most communities would prefer to maintain their languages if given a real choice. They also consider it a scientific problem, because language loss on the scale currently taking place will mean that future linguists will only have access to a fraction of the world's linguistic diversity, therefore their picture of what human language is—and can be—will be limited.[41][42][43][44][45]

Some linguists consider linguistic diversity to be analogous to biological diversity, and compare language endangerment to wildlife endangerment.[46]

Response

Linguists, members of endangered language communities, governments, nongovernmental organizations, and international organizations such as UNESCO and the European Union are actively working to save and stabilize endangered languages.[2] Once a language is determined to be endangered, there are three steps that can be taken in order to stabilize or rescue the language. The first is language documentation, the second is language revitalization and the third is language maintenance.[2]

Language documentation is the documentation in writing and audio-visual recording of grammar, vocabulary, and oral traditions (e.g. stories, songs, religious texts) of endangered languages. It entails producing descriptive grammars, collections of texts and dictionaries of the languages, and it requires the establishment of a secure archive where the material can be stored once it is produced so that it can be accessed by future generations of speakers or scientists.[2]

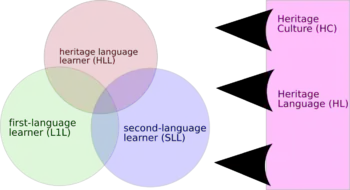

Language revitalization is the process by which a language community through political, community, and educational means attempts to increase the number of active speakers of the endangered language.[2] This process is also sometimes referred to as language revival or reversing language shift.[2] For case studies of this process, see Anderson (2014).[47] Applied linguistics and education are helpful in revitalizing endangered languages.[48] Vocabulary and courses are available online for a number of endangered languages.[49]

Language maintenance refers to the support given to languages that need for their survival to be protected from outsiders who can ultimately affect the number of speakers of a language.[2] UNESCO's strides towards preventing language extinction involves promoting and supporting the language in aspects such as education, culture, communication and information, and science.[50]

Another option is "post-vernacular maintenance": the teaching of some words and concepts of the lost language, rather than revival proper.[51]

As of June 2012 the United States has a "J-1 specialist visa, which allows indigenous language experts who do not have academic training to enter the U.S. as experts aiming to share their knowledge and expand their skills".[52]

See also

- Language ideology

- Language death

- Language Documentation & Conservation (peer-reviewed open-access academic journal)

- Language policy

- Language revitalization

- List of endangered languages with mobile apps

- Lists of endangered languages

- Lists of extinct languages

- List of revived languages

- Minority language

- Native American Languages Act of 1990

- Red Book of Endangered Languages

- The Linguists (documentary film)

- Treasure language

- Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights

- World Poetry Day

Notes

- Crystal, David (2002). Language Death. Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 0521012716.

A language is said to be dead when no one speaks it any more. It may continue to have existence in a recorded form, of course traditionally in writing, more recently as part of a sound or video archive (and it does in a sense 'live on' in this way) but unless it has fluent speakers one would not talk of it as a 'living language'.

- Austin, Peter K; Sallabank, Julia (2011). "Introduction". In Austin, Peter K; Sallabank, Julia (eds.). Cambridge Handbook of Endangered Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88215-6.

- See pp. 55-56 of Zuckermann, Ghil‘ad, Shakuto-Neoh, Shiori & Quer, Giovanni Matteo (2014), Native Tongue Title: Proposed Compensation for the Loss of Aboriginal Languages, Australian Aboriginal Studies 2014/1: 55-71.

- Moseley, Christopher, ed. (2010). Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger. Memory of Peoples (3rd ed.). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 978-92-3-104096-2. Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- Grinevald, Collette & Michel Bert. 2011. "Speakers and Communities" in Austin, Peter K; Sallabank, Julia, eds. (2011). Cambridge Handbook of Endangered Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88215-6. p.50

- Crystal, David (2002). Language Death. England: Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 0521012716.

As a result, without professional guidance, figures in popular estimation see-sawed wildly, from several hundred to tens of thousands. It took some time for systematic surveys to be established. Ethnologue, the largest present-day survey, first attempted a world-wide review only in 1974, an edition containing 5,687 languages.

- Crystal, David (2000). Language Death. Cambridge. p. 3. ISBN 0521653215.

- Grenoble, Lenore A.; Lindsay J. Whaley (1998). "Preface" (PDF). In Lenore A. Grenoble; Lindsay J. Whaley (eds.). Endangered languages: Current Issues and Future Prospects. Cambridge University Press. pp. xi–xii. ISBN 0-521-59102-3.

- "Statistical Summaries". Ethnologue Web Version. SIL International. 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- Endangered languages in Europe: indexes

- ELAR – The Endangered Languages Archive

- "Hand Talk: American Indian Sign Language". Archived from the original on 2014-10-24. Retrieved 2017-09-21.

- Hederpaly, Donna. Tribal "hand talk" considered an endangered language Billings Gazette, August 13, 2010

- Bickford, J. Albert, M. Paul Lewis, Gary F. Simons. 2014. Rating the vitality of sign languages. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 36(5):1-15.

- UNESCO Ad Hoc Expert Group on Endangered Languages (2003). "Language Vitality and Endangerment" (PDF). Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- "UNESCO Interactive Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger". UNESCO.org. 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Languages on Papua Vanish Without a Whisper". Dawn.com. July 21, 2011.

- Krauss, Michael E. (2007). "Keynote – Mass Language Extinction and Documentation: The Race Against Time". In Miyaoka, Osahito; Sakiyama, Osamu; Krauss, Michael E. (eds.). The Vanishing Languages of the Pacific Rim (illustrated ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 3–24. ISBN 978-0199266623. 9780199266623.

- Fishman, Joshua. 1991. Reversing Language Shift. Clevendon: Multilingual Matters.

- Dwyer, Arienne M. 2011. Tools and techniques for endangered-language assessment and revitalization

- Ehala, Martin. 2009. An Evaluation Matrix for Ethnolinguistic Vitality. In Susanna Pertot, Tom Priestly & Colin Williams (eds.), Rights, promotion and integration issues for minority languages in Europe, 123–137. Houndmills: PalgraveMacmillan.

- M. Lynne Landweer. 2011. Methods of Language Endangerment Research: A Perspective from Melanesia. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 212: 153–178.

- Lewis, M. Paul & Gary F. Simons. 2010. Assessing Endangerment: Expanding Fishman’s GIDS. Revue Roumaine de linguistique 55(2). 103–120. Online version Archived 2015-12-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Lee, Nala Huiying, and John Van Way. 2016. Assessing levels of endangerment in the Catalogue of Endangered Languages (ELCat) using the Language Endangerment Index (LEI). Language in Society 45(02):271-292.

- Fulton, Helen (2012). Conceptualizing Multilingualism in England, c. 800 – c. 1250, edited by Elizabeth M. Tyler, Studies in the Early Middle Ages 27, Turnhout, Brepols, pp. 145–170

- With reference to a language shift and Italianization which first started in Sardinia under Savoyard rule in the late 18th century, it is noted that «come conseguenza dell’italianizzazione dell’isola – a partire dalla seconda metà del XVIII secolo ma con un’accelerazione dal secondo dopoguerra – si sono verificati i casi in cui, per un lungo periodo e in alcune fasce della popolazione, si è interrotta la trasmissione transgenerazionale delle varietà locali. [...] Potremmo aggiungere che in condizioni socioeconomiche di svantaggio l’atteggiamento linguistico dei parlanti si è posto in maniera negativa nei confronti della propria lingua, la quale veniva associata ad un’immagine negativa e di ostacolo per la promozione sociale. [...] Un gran numero di parlanti, per marcare la distanza dal gruppo sociale di appartenenza, ha piano piano abbandonato la propria lingua per servirsi della lingua dominante e identificarsi in un gruppo sociale differente e più prestigioso.» Gargiulo, Marco (2013). La politica e la storia linguistica della Sardegna raccontata dai parlanti, in Lingue e diritti. Lingua come fattore di integrazione politica e sociale, Minoranze storiche e nuove minoranze, Atti a cura di Paolo Caretti e Andrea Cardone, Accademia della Crusca, Firenze, pp. 132-133

- In a social process of radical "De-Sardization" amongst the Sardinian families (Bolognesi, Roberto; Heeringa Wilbert, 2005. Sardegna fra tante lingue, il contatto linguistico in Sardegna dal Medioevo a oggi, Cagliari, Condaghes, p. 29), the language shift to Italian and resulting pressure to Italianize commonly seems to entail a general «rifiuto del sardo da parte di chi vuole autopromuoversi socialmente e [chi] si considera "moderno" ne restringe l'uso a persona e contesti "tradizionali" (cioè socialmente poco competitivi), confermando e rafforzando i motivi del rifiuto per mezzo del proprio giudizio sui sardoparlanti» (ivi, pp. 22-23)

- Mary Noebel Noguchi, Sandra Fotos (edited by) (2000). Studies in Japanese Bilingualism. Multilingual Matters Ltd. p. 45–67; 68–97.

- Lalmalsawma, By David. "India speaks 780 languages, 220 lost in last 50 years – survey". Reuters Blogs. Retrieved 2017-01-07.

- Vermondo Brugnatelli (2011). Non solo arabi: le radici berbere nel nuovo Nordafrica, in Limes 5 - 11. pp. 258–259.

- Paris, Brian. The impact of immigrants on language vitality: A case study of Awar and Kayan. Language and Linguistics in Melanesia 32.2: 62-75. Web access.

- Eschner, Kat. "Four Things That Happen When a Language Dies". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2020-01-22.

- Guerin, Valerie (2013). "Language Endangerment". Language of the Pacific Islands: 185.

- Whalen, D. H.; Moss, Margaret; Baldwin, Daryl (9 May 2016). "Healing through language: Positive physical health effects of indigenous language use". F1000Research. 5: 852. doi:10.12688/f1000research.8656.1.

- Dorian, Nancy C. 1978. The Fate of Morphological Complexity in Language Death: Evidence from East Sutherland Gaelic. Language Vol. 54, No. 3: 590–609.

- Schmidt, Annette. 1985. "The Fate of Ergativity in Dying Dyirbal". Language Vol. 61, No. 2: 378–396.

- Ladefoged, Peter 1992. Another view of endangered languages. Language 68(4): 809–11.

- Mufwene, Salikoko (2004). "Language birth and death". Annual Review of Anthropology 33: 201–222.

- Mufwene, Salikoko (2001). The ecology of language evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-511-01934-3.

- Mufwene, Salikoko (2008). Language Evolution: Contact, Competition and Change. Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Hale, Krauss, Watahomigie, Yamamoto, Craig, & Jeanne 1992

- Austin & Sallabank 2011

- Nettle & Romaine 2000

- Skuttnabb-Kangas 2000

- Austin 2009

- Maffi L, ed. 2001. On Biocultural Diversity: Linking Language, Knowledge, and the Environment. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Inst. Press

- "Saving Endangered Languages Before They Disappear". The Solutions Journal. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

- Anderson, Gregory D. S. (2011). "Language Hotspots: what (applied) linguistics and education should do about language endangerment in the twenty-first century". Language and Education. 25 (4): 273–289. doi:10.1080/09500782.2011.577218. S2CID 145802559.

- "Reviews of Language Courses". Lang1234. Retrieved 11 Sep 2012.

- "FAQ on endangered languages | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (August 26, 2009). "Aboriginal Languages Deserve Revival". The Australian Higher Education. Archived from the original on September 23, 2009. Retrieved September 5, 2009.

- "Infinity of Nations: Art and History in the Collections of the National Museum of the American Indian – George Gustav Heye Center, New York". Retrieved 2012-03-25.

References

- Ahlers, Jocelyn C. (September 2012). "Special issue: gender and endangered languages". Gender and Language. Equinox. 6 (2).

- Abley, Mark (2003). Spoken Here: Travels Among Threatened Languages. London: Heinemann.

- Crystal, David (2000). Language Death. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521012713.

- Evans, Nicholas (2001). "The Last Speaker is Dead – Long Live the Last Speaker!". In Newman, Paul; Ratliff, Martha (eds.). Linguistic Field Work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 250–281..

- Hale, Kenneth; Krauss, Michael; Watahomigie, Lucille J.; Yamamoto, Akira Y.; Craig, Colette; Jeanne, LaVerne M. et al. 1992. Endangered Languages. Language, 68 (1), 1–42.

- Harrison, K. David. 2007. When Languages Die: The Extinction of the World's Languages and the Erosion of Human Knowledge. New York and London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-518192-1.

- McConvell, Patrick; Thieberger, Nicholas (2006). "Keeping Track of Language Endangerment in Australia". In Cunningham, Denis; Ingram, David; Sumbuk, Kenneth (eds.). Language Diversity in the Pacific: Endangerment and Survival. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. pp. 54–84. ISBN 1853598674.

- McConvell, Patrick and Thieberger, Nicholas. 2001. State of Indigenous Languages in Australia – 2001 (PDF), Australia State of the Environment Second Technical Paper Series (Natural and Cultural Heritage), Department of the Environment and Heritage, Canberra.

- Nettle, Daniel and Romaine, Suzanne. 2000. Vanishing Voices: The Extinction of the World's Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Skutnabb-Kangas, Tove (2000). Linguistic Genocide in Education or Worldwide Diversity and Human Rights?. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 0-8058-3468-0.

- Zuckermann, Ghil'ad and Walsh, Michael. 2011. 'Stop, Revive, Survive: Lessons from the Hebrew Revival Applicable to the Reclamation, Maintenance and Empowerment of Aboriginal Languages and Cultures', Australian Journal of Linguistics Vol. 31, No. 1, pp. 111–127.

- Austin, Peter K; Sallabank, Julia, eds. (2011). Cambridge Handbook of Endangered Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88215-6.

- Fishman, Joshua. 1991. Reversing Language Shift. Clevendon: Multilingual Matters.

- Ehala, Martin. 2009. An Evaluation Matrix for Ethnolinguistic Vitality. In Susanna Pertot, Tom Priestly & Colin Williams (eds.), Rights, Promotion and Integration Issues for Minority Languages in Europe, 123–137. Houndmills: PalgraveMacmillan.

- Landweer, M. Lynne. 2011. Methods of Language Endangerment Research: a Perspective from Melanesia. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 212: 153–178.

- Lewis, M. Paul & Gary F. Simons. 2010. Assessing Endangerment: Expanding Fishman's GIDS. Revue Roumaine de linguistique 55(2). 103–120. Online version of the article.

- Hinton, Leanne and Ken Hale (eds.) 2001. The Green Book of Language Revitalization in Practice. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Gippert, Jost; Himmelmann, Nikolaus P. and Mosel, Ulrike (eds.) 2006. Essentials of Language Documentation (Trends in Linguistics: Studies and Monographs 178). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Fishman, Joshua. 2001a. Can Threatened Languages be Saved? Reversing Language Shift, Revisited: A 21st Century Perspective. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Dorian, Nancy. 1981. Language Death: The Life Cycle of a Scottish Gaelic Dialect. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Campbell, Lyle and Muntzel, Martha C.. 1989. The Structural Consequences of Language Death. In Dorian, Nancy C. (ed.), Investigating Obsolescence: Studies in Language Contraction and Death, 181–96. Cambridge University Press.

- Boas, Franz. 1911. Introduction. In Boas, Franz (ed.) Handbook of American Indian Languages Part I (Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 40), 1–83. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Austin, Peter K. (ed.). 2009. One Thousand Languages: Living, Endangered, and Lost. London: Thames and Hudson and Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- “One Thousand Languages: Living, Endangered and Lost,” edited by Peter K. Austin. University of California Press (2008) http://www.economist.com/node/12483451.

- Whalen, D. H., & Simons, G. F. (2012). Endangered language families. Language, 88(1), 155–173.

Further reading

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Endangered languages |

- "Endangered Languages at the UNESCO official Website".

- "Endangered Language Resources at the LSA".

- Resource Network for Linguistic Diversity

- Endangered Languages Project

- Akasaka, Rio; Machael Shin; Aaron Stein (2008). "Endangered Languages: Information and Resources on Dying Languages". Endangered-Languages.com. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- "Bibliography of Materials on Endangered Languages". Yinka Déné Language Institute (YDLI). 2006. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- Constantine, Peter (2010). "Is There Hope for Europe's Endangered Native Tongues?". The Quarterly Conversation. Archived from the original on 2010-06-24. Retrieved 2010-06-29.

- "Endangered languages". SIL International. 2009. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- Headland, Thomas N. (2003). "Thirty Endangered Languages in the Philippines" (PDF). Dallas, Texas: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

- Horne, Adele; Peter Ladefoged; Rosemary Beam de Azcona (2006). "Interviews on Endangered Languages". Arlington, Virginia: Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- Malone, Elizabeth; Nicole Rager Fuller (2008). "A Special Report: Endangered Languages". National Science Foundation. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- "Nearly Extinct Languages". Electronic Metadata for Endangered Languages Data (E-MELD). 2001–2008. Archived from the original on 2011-07-26. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- Salminen, Tapani (1998). "Minority Languages in a Society in Turmoil: The Case of the Northern Languages of the Russian Federation". In Ostler, Nicholas (ed.). Endangered Languages: What Role for the Specialist? Proceedings of the Second FEL Conference (new ed.). Edinburgh: Foundation for Endangered Languages & Helsinki University. pp. 58–63.

- "Selected Descriptive, Theoretical and Typological Papers (index)". Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages. 1997–2007. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- "Winona LaDuke Speaks on Biocultural Diversity, Language and Environmental Endangerment". The UpTake. 2012-03-29. Retrieved 2012-08-08.

Organizations

- Linguistic Society of America

- Hans Rausing Endangered Languages Project

- Documenting Endangered Languages, National Science Foundation

- Society to Advance Indigenous Vernaculars of the United States, (Savius.org)

- Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival

- Indigenous Language Institute

- International Conference on Language Documentation and Conservation

- Sorosoro

- Enduring Voices Project, National Geographic

- Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages

- Endangered Language Alliance, New York City

- Endangered Languages Project

- DoBeS Documentation of endangered languages

- CILLDI, Canadian Indigenous Languages Literacy and Development Institute

Technologies

- Recording your elder/Native speaker, practical vocal recording tips for non-professionals

- Learning indigenous languages on Nintendo

- Pointers on How to Learn Your Language (scroll to link on page)

- First Nations endangered languages chat applications

- Do-it-yourself grammar and reading in your language, Breath of Life 2010 presentations