Italianization

Italianization (Italian: Italianizzazione; Croatian: talijanizacija; French: italianisation; Slovene: poitaljančevanje; German: Italianisierung; Greek: Ιταλοποίηση) is the spread of Italian culture, language and identity by way of integration or assimilation.[1][2]

It is also known for a process organized by the Kingdom of Italy to force cultural and ethnic assimilation of the native populations living, primarily, in the former Austro-Hungarian territories that were transferred to Italy after World War I in exchange for Italy having joined the Triple Entente in 1915; this process was mainly conducted during the period of Fascist rule between 1922 and 1943.

Regions and populations affected

Between 1922 and the beginning of World War II, the affected people were the German-speaking and Ladin-speaking populations of Trentino-Alto Adige, and Slovenes and Croats in the Julian March. The program was later extended to areas annexed during World War II, affecting Slovenes in the Province of Ljubljana, and Croats in Gorski Kotar and coastal Dalmatia, Greeks in the Ionian islands and, to a lesser extent, to the French- and Arpitan-speaking regions of the western Alps (such as the Aosta valley). On the other hand, the island of Sardinia had already undergone cultural and linguistic Italianization starting from an earlier period.

Istria, Julian March and Dalmatia

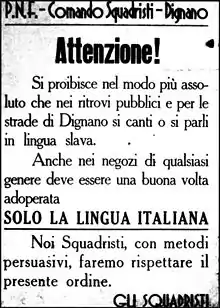

The former Austrian Littoral (later renamed the Julian March) was occupied by the Italian Army after the Armistice with Austria. Following the annexation of the March by Italy, 400[3] cultural, sporting (for example Sokol), youth, social and professional Slavic organizations, and libraries ("reading rooms"), three political parties, 31 newspapers and journals, and 300 co-operatives and financial institutions had been forbidden, and specifically so later with the Law on Associations (1925), the Law on Public Demonstrations (1926) and the Law on Public Order (1926), the closure of the classical lyceum in Pazin, of the high school in Volosko (1918), the closure of the 488[3] Slovene and Croat primary schools followed.

The period of violent persecution of Slovenes in Trieste began with riots on 13 April 1920, which were organized as a retaliation for the assault on the Italian occupying troops by the local Croatian population in the 11 July Split incident. Many Slovene-owned shops and buildings were destroyed during the riots, which culminated in the burning down of the Narodni dom ("National House"), the community hall of the Triestine Slovenes, by a group of Italian Fascists, led by Francesco Giunta.[4] Benito Mussolini praised this action as a "masterpiece of the Triestine fascism". Two years later he became prime minister of Italy.[5]

In September 1920, Mussolini said:

When dealing with such a race as Slavic – inferior and barbaric – we must not pursue the carrot, but the stick policy. We should not be afraid of new victims. The Italian border should run across the Brenner Pass, Monte Nevoso and the Dinaric Alps. I would say we can easily sacrifice 500,000 barbaric Slavs for 50,000 Italians.

This expressed a common Fascist opinion against the Croatian and Slovene minority in the Julian March.[5]

Italian teachers were assigned to schools and the use of Croatian and Slovene languages in the administration and in the courts restricted. After March 1923 these languages were prohibited in administration, and after October 1925 in law courts, as well. In 1923, in the context of the organic school reform prepared by the fascist minister Giovanni Gentile, teaching in languages different from Italian was abolished. In the Julian March this meant the end of teaching in Croatian and Slovenian. Some 500 Slovene teachers, nearly half of all Slovene teachers in the Littoral region, were moved by the Italians from the area, to the interior of Italy, while Italian teachers were sent to teach Slovene children Italian.[7] However, in Šušnjevica (it: Valdarsa) the use of Istro-Rumanian language was allowed after 1923.[8]

In 1926, claiming that it was restoring surnames to their original Italian form, the Italian government announced the Italianization of German, Slovene and Croat surnames.[9][10] In the Province of Trieste alone, 3,000 surnames were modified and 60,000 people had their surnames amended to an Italian-sounding form.[3] First or given names were also Italianized.

Slovene and Croat societies and sporting and cultural associations had to cease every activity in line with a decision of provincial Fascist secretaries dated 12 June 1927. On a specific order from the prefect of Trieste on 19 November 1928, the Edinost political society was also dissolved. Croat and Slovene financial co-operatives in Istria, which at first were absorbed by the Pula or Trieste savings banks, were gradually liquidated.[11]

In 1927, Giuseppe Cobolli Gigli, the minister for public works in fascist Italy, wrote in Gerarchia magazine, a Fascist publication, that "The Istrian muse named as Foibe those places suitable for burial of enemies of the national [Italian] characteristics of Istria".[12][13][14][15]

The Slovene militant anti-Fascist organization TIGR emerged in 1927. It co-ordinated the Slovene resistance against Fascist Italy until its dismantlement by the Fascist secret police in 1941. At the time, some TIGR ex-members joined the Slovene Partisans.

As a result of the repression, more than 100,000 Slovenes and Croats emigrated from Italian territory between the two world wars, the vast majority to Yugoslavia.[7] Among the notable Slovene émigrés from Trieste were the writers Vladimir Bartol and Josip Ribičič, the legal theorist Boris Furlan, and the architect Viktor Sulčič.

World War II war crimes

During World War II Italy attacked Yugoslavia, and occupied large portions of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Montenegro, Serbia and Macedonia, directly annexing Ljubljana Province, Gorski Kotar and Central Dalmatia along with most Croatian islands. In Dalmatia the Italian government made stringent efforts to Italianize the region. Italian occupying forces were accused of committing war crimes in order to transform occupied territories into ethnic Italian territories.[16]

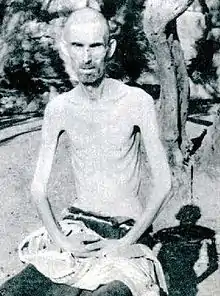

The Italian government sent tens-of-thousands of Slavic citizens, among them many women and children, to Italian concentration camps,[17] such as Rab concentration camp, Gonars, Monigo, Renicci, Molat, Zlarin, Mamula, etc. From Ljubljana Province alone, historians estimate the Italians sent 25,000 to 40,000[18] Slovenes to concentration camps, which represents 8-12% of the total population. Thousands died in the camps, including hundreds of children.[19] Survivors received no compensation from Italy after the war.

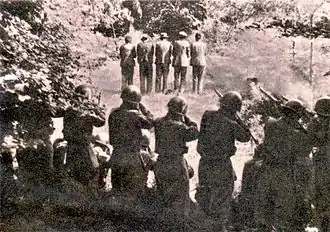

Mario Roatta was the commander of the Italian 2nd Army in Yugoslavia. To suppress the mounting resistance led by the Slovene and Croat partisans, he adopted tactics of "summary executions, hostage-taking, reprisals, internments and the burning of houses and villages."[20] After the war the Yugoslav government sought unsuccessfully to have him extradited for war crimes from Spain, where he was protected by Francisco Franco.[21] Mario Robotti issued an order in line with a directive received from Mussolini in June 1942: "I would not be opposed to all (sic) Slovenes being imprisoned and replaced by Italians. In other words, we should take steps to ensure that political and ethnic frontiers coincide."[21]

Ionian Islands

The cultural remnants of the Venetian period were Mussolini's pretext to incorporate the Ionian Islands into the Kingdom of Italy.[22] Even before the outbreak of World War II and the Greek-Italian 1940-1941 Winter War, Mussolini had expressed his wish to annex the Ionian Islands as an Italian province.[23] After the fall of Greece in early April 1941, the Italians occupied much of the country, including the Ionians. Mussolini informed General Carlo Geloso that the Ionian Islands would form a separate Italian province through a de facto annexation, but the Germans would not approve it. Nevertheless, the Italian authorities continued to prepare the ground for the annexation. Finally, on 22 April 1941, after discussions between the German and Italian rulers, Hitler agreed that Italy could proceed with a de facto annexation of the islands. Thus on 10 August 1941 the islands of Corfu, Cephalonia, Zakynthos, Lefkada and some minor islands were officially annexed by Italy as part of the Grande Communità del Nuovo Impero Romano (Great Community of the New Roman Empire).

As soon as the fascist governor Piero Parini had installed himself on Corfu he vigorously began a forced Italianization policy that lasted until the end of the war.[24] The islands passed through a phase of Italianization in all areas, from their administration to their economy. Italian was designated the islands' only official language; a new currency, the Ionian drachma, was introduced with the aim to hamper trade with the rest of Greece, which was forbidden by Parini. Transportation with continental Greece was limited; in the courts, judges had to apply Italian law, and schooling followed the educational model of the Italian mainland. Greek administrative officials were replaced by Italian ones, administrative officials of non-Ionic origin were expelled, the local gendarmes were partially replaced by Italian Carabinieri, although Parini initially allowed the Greek judges to continue their work, they were ultimately replaced by an Italian Military Court based in Corfu. The "return to the Venetian order" and the italianization as pursued by Parini were even more drastic than the italianization policies elsewhere, as their aim was a forced and abrupt cessation of all cultural and historical ties with the old mother country. The only newspaper on the islands was the Italian language "Giornale del Popolo".[24][25][26][27] By early 1942 pre-war politicians in the Ionian Islands began to protest Parini's harsh policies. Parini reacted by opening a concentration camp on the island of Paxi, to which two more camps were added on Othonoi and Lazaretto islands. Parini's police troops arrested about 3,500 people, which were imprisoned at these three camps.[24] The Italianization efforts in the Ionian islands ended in September 1943, after the armistice of Cassibile.

Dodecanese islands

The twelve major islands of the Dodecanese, of which the largest is Rhodos, were ruled by Italy between 1912 and 1945. After a period of military rule, civil governors were appointed in 1923 shortly after Fascists began to rule Italy and Italians were settled on the islands. The first governor, Mario Lago, encouraged intermarriage between Italian settlers and Greeks, provided scholarships for young Greeks to study in Italy and set up a Dodecanese church to limit the influence of the Greek Orthodox Church. Fascist youth organizations were introduced on the islands, and the Italianization of names was encouraged by the Italian authorities. The islanders did, however, not receive full citizenship and were not required to serve in the Italian armed forces. The population was allowed to elect their own mayors. Lagos' successor, Cesare Maria De Vecchi, embarked on a forced Italianization campaign in 1936. The Italian language became compulsory in education and the public life, with Greek being only an optional subject in schools. In 1937 the elected mayors were replaced by appointed loyal fascists. in 1938, the new Italian Racial Laws were introduced to the islands.[28]

South Tyrol

In 1919, at the time of its annexation, the southern part of Tyrol was inhabited by almost 90% German speakers.[29] In October 1923, the use of the Italian language became mandatory (although not exclusive) on all levels of federal, provincial and local government.[30] Regulations by the fascist authorities required that all kinds of signs and public notices be in Italian only. Maps, postcards and other graphic material had to show Italian place names.[30] In September 1925, Italian became the sole permissible language in courts of law.[30] Illegal Katakombenschulen ("Catacomb schools") were set up by the local German-speaking minority to teach children the German language. The government created incentives to encourage immigration of native Italians to the South Tyrol.

Several factors limited the effects of the Italian policy, namely the adverse nature of the territory (mainly mountains and valleys of difficult access), the difficulty for the Italian-speaking individuals to adapt to a completely different environment and, later on, the alliance between Germany and Italy: under the 1939 South Tyrol Option Agreement, Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini determined the status of the German people living in the province. They either had to opt for emigration to Germany or stay in Italy and become fully Italianized. Because of the outbreak of World War II, this agreement was never fully implemented and most ethnic Germans remained or returned at the end of the war.

Following World War II, South Tyrol was one of the first regions to be granted autonomy on the ground of its peculiar linguistic situation; any further attempts at Italianization were formerly abandoned. In the 21st century, just over 100 years after the Italian annexation of the region,[31] 64% of the population of South Tyrol speak German dialects as their first and everyday language.

Sardinia

In 1720, the island of Sardinia had been ceded to Alpine House of Savoy, which at the time already controlled a number of other states in the Italian mainland, most notably Piedmont. The Savoyards had imposed the Italian language on Sardinia as part of a wider cultural policy designed to bind the island to the Mainland in such a way as to prevent either future attempts of political separation or curb a renewed interest on the part of Spain. In fact, the complex linguistic composition of the islanders, theretofore extraneous to Italian and its cultural sphere, had been previously roofed by Spanish as the prestige language of the upper class for centuries; in this context, Italianization, while difficult, was intended as a cultural policy whereby the social and economic structures of the island could become increasingly intertwined with the Mainland and expressly Piedmont, where the Kingdom's central power lay.[32] The 1847 Perfect Fusion, performed with an assimilationist intent[33] and politically analogous to the Acts of Union between Britain and Ireland, determined the conventional moment wherefrom the Sardinian language ceased to be regarded as an identity marker of a specific ethnic group, and was instead lumped in with the Mainland's dialectal conglomerate already subordinate to the national language.[34][35] The jurist Carlo Baudi di Vesme, in his 1848 essay Considerazioni politiche ed economiche sulla Sardegna, stated that Sardinian was one of the most significant barriers separating the islanders from the Italian Mainland, and only the suppression of their dialects could ensure that they might understand the governmental instructions, issued in Italian, and become properly "civilized" subjects of the Savoyard Kingdom.[36]

However, it was not until the rise of fascism that Sardinian was actively banned and/or excluded from any residual cultural activities to enforce a thorough shift to Italian.[37][38][39]

After the end of the Second World War, efforts continued to be made to further Italianize the population, with the justification that by doing so, as the principles of the modernization theory ran, the island could rid itself of the ancient "traditional practices" which held it back, regarded as a legacy of barbarism to be disposed of at once in order to join the Mainland's economic growth;[40] Italianization had thus become a mass phenomenon, taking roots in the hitherto predominantly Sardinian-speaking villages.[41] To many Sardinians, abandoning their language and acquiring Italian as a cultural norm represented a means through which they could distance themselves from their original group, which they perceived as marginalized and lacking in prestige, and thereby incorporate themselves into an altogether different social group.[42] The Sardinians have been thus led to part with their language as it bore the mark of a stigmatized identity,[43] the embodiment of a long-suffered social and political subordination in a chained society, as opposed to the social advancement granted them by embracing Italian.[44] Research on ethnolinguistic prejudice has pointed to feelings of inferiority amongst the Sardinians in relation with Italians and the Italian language, perceived as a symbol of continental superiority and cultural dominance.[45] Many indigenous cultural practices were to go extinct, shifting towards other forms of socialization.[41] Within a few generations Sardinian, as well as Alghero's Catalan dialect, would become a minority language spoken by fewer and fewer Sardinian families, the majority of whom have turned into monolingual and monocultural Italians.[46][47] This process has been slower to take hold in the countryside than in the main cities, where it became most evident instead.[48]

Nowadays, the Sardinians are linguistically and culturally Italianized and, despite the official recognition conferred to Sardinian by the national law, "identify with their language to lesser degree than other linguistic minorities in Italy, and instead seem to identify with Italian to a higher degree than other linguistic minorities in Italy".[49][35] It is estimated that around 10 to 13 percent of the young people born in Sardinia are still competent in Sardinian,[50][51] and the language is currently used exclusively by 0.6% of the total population.[52] A 2012 study conducted by the University of Cagliari and Edinburgh found that the interviewees from Sardinia with the strongest sense of Italian identity were also those expressing the most unfavourable opinion towards Sardinian, as well as the promotion of regional autonomy.[53]

References

- "Processo di assimilazione alla cultura italiana." "Italianizzazione". Dizionario della Lingua Italiana Sabatini Coletti.

- «1)Trans.: Rendere italiano; comunicare, trasfondere la cultura, i sentimenti, gli ideali, le abitudini, le leggi e il linguaggio propri degli Italiani. 2) Far assumere una forma italiana a un nome, a un vocabolo, a una struttura letteraria; adattare secondo le leggi fonetiche, morfologiche, grammaticali della lingua italiana; tradurre in italiano. 3) Intr. con la particella pronom.: Diventare italiano; uniformarsi ai modi, alle tradizioni, alle abitudini, alle leggi degli Italiani; assimilarne i sentimenti, le aspirazioni, gli ideali.» Battaglia, Salvatore (1961). Grande dizionario della lingua italiana, UTET, Torino, V. VIII, p.625.

- Cresciani, Gianfranco (2004) Clash of civilisations, Italian Historical Society Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, p. 4

- "90 let od požiga Narodnega doma v Trstu" [90 Years From the Arson of the National Hall in Trieste]. Primorski dnevnik [The Littoral Daily] (in Slovenian). 2010. pp. 14–15. COBISS 11683661. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

|chapter=ignored (help) - Sestani, Armando, ed. (10 February 2012). "Il confine orientale: una terra, molti esodi" [The Eastern Border: One Land, Multiple Exoduses]. Gli esuli istriani, dalmati e fiumani a Lucca [The Istrian, Dalmatian and Rijeka Refugees in Lucca] (in Italian). Instituto storico della Resistenca e dell'Età Contemporanea in Provincia di Lucca. pp. 12–13.

- Verginella, Marta (2011). "Antislavismo, razzismo di frontiera?". Aut aut (in Italian). ISBN 9788865761069.

- "dLib.si – Izseljevanje iz Primorske med obema vojnama". www.dlib.si. Retrieved 2020-04-08.

- PUŞCARIU, Sextil. Studii istroromâne. Vol. II, București: 1926

- Regio decreto legge 10 Gennaio 1926, n. 17: Restituzione in forma italiana dei cognomi delle famiglie della provincia di Trento

- Mezulić, Hrvoje; R. Jelić (2005) Fascism, baptiser and scorcher (O Talijanskoj upravi u Istri i Dalmaciji 1918–1943.: nasilno potalijančivanje prezimena, imena i mjesta), Dom i svijet, Zagreb, ISBN 953-238-012-4

- A Historical Outline Of Istria Archived 2008-01-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Gerarchia, vol. IX, 1927: "La musa istriana ha chiamato Foiba degno posto di sepoltura per chi nella provincia d'Istria minaccia le caratteristiche nazionali dell'Istria"(in Serbian)

- (in Serbian)http://www.danas.rs/20050217/dijalog1.html Archived 2012-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Italian) http://www.lavocedifiore.org/SPIP/article.php3?id_article=1692

- (in Italian)http://www.osservatoriobalcani.org/article/articleview/3901/1/176/

- Z. Dizdar: "Italian Policies Toward Croatians In Occupied Territories During The Second World War", Review of Croatian History Issue no.1 /2005

- Elenco Dei Campi Di Concentramento Italiani

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2002). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia: 1941–1945. Stanford University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-8047-7924-1.

- Oltre il filo (Trailer), retrieved 2020-04-09

- General Roatta's War against the Partisans in Yugoslavia: 1942, IngentaConnect

- Tommaso Di Francesco and Giacomo Scotti, "Sixty Years of Ethnic Cleansing", Le Monde Diplomatique, 8 May 1999

- Rodogno, Davide (2003). Il nuovo ordine mediterraneo : le politiche di occupazione dell'Italia fascista in Europa (1940 - 1943) (1. ed.). Torino: Bollati Boringhieri. p. 586. ISBN 978-8833914329.

- MacGregor, Knox (1986). Mussolini Unleashed, 1939-1941: Politics and Strategy in Fascist Italy's Last War. Cambridge University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0521338356.

- Commissione Italiana di Storia Militare (1993). L'Italia in Guerra - Il Terzo Anno 1942. Rome: Italian Ministry of Defense. p. 370. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- Vallianatos, Markos (2014). The untold history of Greek collaboration with Nazi Germany (1941–1944). p. 74. ISBN 978-1304845795.

- Commissione Italiana di Storia Militare (1993). L'Italia in Guerra – Il Terzo Anno 1942. Rome: Italian Ministry of Defense. p. 370. Retrieved 5 November 2016.

- Rodogno, Davide (3 August 2006). Fascism's European Empire: Italian Occupation During the Second World War. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521845151.

- Aegeannet, The Dodecanese under Italian Rule Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Oscar Benvenuto (ed.): "South Tyrol in Figures 2008", Provincial Statistics Institute of the Autonomous Province of South Tyrol, Bozen/Bolzano 2007, p. 19, Table 11

- Steininger, Rolf (2003), p. 23-24

- "astat info Nr. 38" (PDF). Table 1 — Declarations of which language group belong to/affiliated to — Population Census 2011. Retrieved 2012-06-12.

- Omar Onnis (2015). La Sardegna e i sardi nel tempo. Arkadia. p. 143.

- According to Pietro Martini, who stood at the forefront for the cause and rose to become one of its leading exponents, the Fusion may have opened the way to "the transplant, without any reserves and obstacles, of the culture and civilization of the Italian Mainland to Sardinia, and thereby form a single civil family under a Father better than a King, the great Charles Albert". (Pietro Martini (1847). Sull'unione civile della Sardegna colla Liguria, col Piemonte e colla Savoia. Cagliari: Timon. p. 4.)

- «...la 'lingua della sarda nazione' perse il valore di strumento di identificazione etnica di un popolo e della sua cultura, da codificare e valorizzare, per diventare uno dei tanti dialetti regionali subordinati alla lingua nazionale." Dettori, Antonietta, 2001. Sardo e italiano: tappe fondamentali di un complesso rapporto, in Argiolas, Mario; Serra, Roberto. Limba lingua language: lingue locali, standardizzazione e identità in Sardegna nell'era della globalizzazione, Cagliari, CUEC, p. 88

- Naomi Wells (2012). Multilinguismo nello Stato-Nazione, in Contarini, Silvia; Marras, Margherita; Pias, Giuliana. L'identità sarda del XXI secolo tra globale, locale e postcoloniale. Nuoro: Il Maestrale. p. 158.

- Carlo Baudi di Vesme (1848). Considerazioni politiche ed economiche sulla Sardegna. Dalla Stamperia Reale. pp. 49–51.

- "Dopo pisani e genovesi si erano susseguiti aragonesi di lingua catalana, spagnoli di lingua castigliana, austriaci, piemontesi ed, infine, italiani [...] Nonostante questi impatti linguistici, la "limba sarda" si mantiene relativamente intatta attraverso i secoli. [...] Fino al fascismo: che vietò l'uso del sardo non solo in chiesa, ma anche in tutte le manifestazioni folkloristiche.» De Concini, Wolftraud (2003). Gli altri d'Italia : minoranze linguistiche allo specchio, Pergine Valsugana : Comune, p.195-196.

- "Il ventennio fascista – come ha affermato Manlio Brigaglia ‒ segnò il definitivo ingresso della Sardegna nel 'sistema' nazionale. L'isola fu colonialisticamente integrata nella cultura nazionale: modi di vita, costumi, visioni generali, parole d'ordine politiche furono imposte sia attraverso la scuola, dalla quale partì un'azione repressiva nei confronti dell'uso della lingua sarda, sia attraverso le organizzazioni del partito." Garroni, M. (2010). La Sardegna durante il ventennio fascista

- Omar Onnis (2015). La Sardegna e i sardi nel tempo. Arkadia. p. 204.

- Omar Onnis (2015). La Sardegna e i sardi nel tempo. Arkadia. pp. 215–216.

- Omar Onnis (2015). La Sardegna e i sardi nel tempo. Arkadia. p. 216.

- "Come conseguenza dell'italianizzazione dell'isola – a partire dalla seconda metà del XVIII secolo ma con un'accelerazione dal secondo dopoguerra – si sono verificati i casi in cui, per un lungo periodo e in alcune fasce della popolazione, si è interrotta la trasmissione transgenerazionale delle varietà locali. [...] Potremmo aggiungere che in condizioni socioeconomiche di svantaggio l'atteggiamento linguistico dei parlanti si è posto in maniera negativa nei confronti della propria lingua, la quale veniva associata ad un'immagine negativa e di ostacolo per la promozione sociale. [...] Un gran numero di parlanti, per marcare la distanza dal gruppo sociale di appartenenza, ha piano piano abbandonato la propria lingua per servirsi della lingua dominante e identificarsi in un gruppo sociale differente e più prestigioso.» Gargiulo, Marco (2013). La politica e la storia linguistica della Sardegna raccontata dai parlanti, in Lingue e diritti. Lingua come fattore di integrazione politica e sociale, Minoranze storiche e nuove minoranze, Atti a cura di Paolo Caretti e Andrea Cardone, Accademia della Crusca, Firenze, pp. 132-133

- «La tendenza che caratterizza invece molti gruppi dominati è quella di gettare a mare i segni che indicano la propria appartenenza a un'identità stigmatizzata. È quello che accade in Sardegna con la sua lingua (capp. 8-9, in questo volume)." Mongili, Alessandro (2015). Topologie postcoloniali. Innovazione e modernizzazione in Sardegna, Chapt. 1: Indicible è il sardo

- "...Per la più gran parte dei parlanti, la lingua sarda è sinonimo o comunque connotato di un passato misero e miserabile che si vuole dimenticare e di cui ci si vuole liberare, è il segno della subordinazione sociale e politica; la lingua di classi più che subalterne e per di più legate a modalità di vita ormai ritenuta arcaica e pertanto non desiderabile, la lingua degli antichi e dei bifolchi, della ristrettezza e della chiusura paesane contro l'apertura, nazionale e internazionale, urbana e civile." Virdis, Maurizio (2003). La lingua sarda oggi: bilinguismo, problemi di identità culturale e realtà scolastica, cit. in Convegno dalla lingua materna al plurilinguismo, Gorizia, 4.

- "It turns out that the Italian: Sardinian dichotomy is not so much realized in the form of affective group-images, but that Italian is generally perceived as symbolizing continental superiority and cultural dominance. In her dissertation on ethnolinguistic prejudice, Diana (1981) points to the feelings of inferiority Sardinians have in relation to Italians.» Rebecca Posner, John N. Green (1993). Bilingualism and Linguistic Conflict in Romance. De Gruyter Mouton. p. 279.

- «Gli effetti di una italianizzazione esasperata - iniziata e voluta dai Savoia fin dal lontano 1861 con l'Unità d'Italia - riprendevano fiato e vigore, mentre il vocabolario sardo andava ormai alleggerendosi, tagliando molti di quei termini perché non più appropriati alla tecnologia emergente o perché lontani dalla dalla mentalità e dall'azione delle nuove generazioni che andavano ormai identificandosi nella lingua e nella cultura imposte dal "sistema" italiano, che ignorava la lingua e la cultura dei nostri padri.» Melis Onnis, Giovanni (2014). Fueddariu sardu campidanesu-italianu, Domus de Janas, Presentazione

- «...se è vero che la lingua è memoria attiva, struttura del ragionamento, cosmo delle emozioni; altrimenti tutto ciò che ci appartiene rischia di esser visto, anche e proprio a casa nostra, da noi stessi voglio dire, con gli occhi dello straniero che guarda l'esotico: e non esagero nel dire ciò, nei centri urbani e nei ceti urbanizzati si pensa alle cose della tradizione o della specificità sarda con le parole della pubblicità di un agenzia turistica. [...] Bisogna partire dal constatare che il processo di 'desardizzazione' culturale ha trovato spunto e continua a trovare alimento nella desardizzazione linguistica, e che l'espropriazione culturale è venuta e viene a rimorchio dell'espropriazione linguistica." Virdis, Maurizio (2003). La lingua sarda oggi: bilinguismo, problemi di identità culturale e realtà scolastica, cit. in Convegno dalla lingua materna al plurilinguismo, Gorizia, 5-6.

- "The results of the Oristano surveys seem to show that the change in the use of the two languages is taking place very quickly ([...]), while the detailed studies of Ottava and Bonorva (Province of Sassari) show that Italianization in the countryside is hampered by the lack of social mobility and by the normative pressure of the rural Sardinian-speaking community network." Rosita Rinler Shjerve (1997). Kontaktlinguistik / Contact Linguistics / Linguistique de contact, v. 2. Berlin & New-York: Walter de Gruyter. p. 1379.

- "[I sardi] si identificano con loro lingua meno di quanto facciano altre minoranze linguistiche esistenti in Italia, e viceversa sembrano identificarsi con l'italiano più di quanto accada per altre minoranze linguistiche d'Italia." Paulis, Giulio (2001). Il sardo unificato e la teoria della panificazione linguistica, in Argiolas, Mario; Serra, Roberto, Limba lingua language: lingue locali, standardizzazione e identità in Sardegna nell’era della globalizzazione, Cagliari, CUEC, p. 16)

- Coretti, Paolo, 04/11/2010, La Nuova Sardegna, Per salvare i segni dell'identità

- Piras, Luciano, 05/02/2019, La Nuova Sardegna, Silanus diventa la capitale dei vocabolari dialettali

- ISTAT, lingue e dialetti, tavole

- Gianmario Demuro; Francesco Mola (2013). Ilenia Ruggiu (ed.). Identità e autonomia in Sardegna e Scozia. Santarcangelo di Romagna: Maggioli Editore. pp. 38–39.