Julian (emperor)

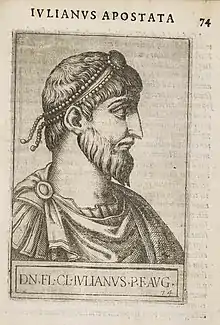

Julian[lower-roman 1] (Latin: Flavius Claudius Julianus; Greek: Ἰουλιανός; 331 – 26 June 363) was Roman emperor from 361 to 363, as well as a notable philosopher and author in Greek.[3] His rejection of Christianity, and his promotion of Neoplatonic Hellenism in its place, caused him to be remembered as Julian the Apostate by the Christian Church.[4][5]

| Julian | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

-CNG.jpg.webp) Portrait of Emperor Julian on a bronze coin from Antioch. Legend: d n Fl Cl Iulianus p f aug. | |||||||||

| Roman emperor | |||||||||

| Augustus | 3 November 361 – 26 June 363 (proclaimed in early 360) | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Constantius II | ||||||||

| Successor | Jovian | ||||||||

| Caesar | 6 November 355 – early 360 | ||||||||

| Born | 331 Constantinople | ||||||||

| Died | 26 June 363 (aged 31 or 32) Frygium, Mesopotamia | ||||||||

| Burial | |||||||||

| Spouse | Helena | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynasty | Constantinian | ||||||||

| Father | Julius Constantius | ||||||||

| Mother | Basilina | ||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||

A member of the Constantinian dynasty, Julian was orphaned as a child. He was raised by the Gothic slave Mardonius, who had a profound influence on him, providing Julian with an excellent education.[6] Julian became caesar over the western provinces by order of Constantius II in 355, and in this role he campaigned successfully against the Alamanni and Franks. Most notable was his crushing victory over the Alamanni at the Battle of Argentoratum (Strasbourg) in 357, leading his 13,000 men against a Germanic army three times larger. In 360, Julian was proclaimed Augustus by his soldiers at Lutetia (Paris), sparking a civil war with Constantius. However, Constantius died before the two could face each other in battle, and named Julian as his successor.

In 363, Julian embarked on an ambitious campaign against the Sasanian Empire. The campaign was initially successful, securing a victory outside Ctesiphon in Mesopotamia.[7] However, he did not attempt to besiege the capital and moved into Persia's heartland, but soon faced supply problems and was forced to retreat northwards while ceaselessly being harassed by Persian skirmishes. During the Battle of Samarra, Julian was mortally wounded under mysterious circumstances.[8][6] He was succeeded by Jovian, a senior officer in the imperial guard, who was obliged to cede territory, including Nisibis, in order to save the trapped Roman forces.[9]

Julian was a man of unusually complex character: he was "the military commander, the theosophist, the social reformer, and the man of letters".[10] He was the last non-Christian ruler of the Roman Empire, and he believed that it was necessary to restore the Empire's ancient Roman values and traditions in order to save it from dissolution.[11] He purged the top-heavy state bureaucracy, and attempted to revive traditional Roman religious practices at the expense of Christianity. His attempt to build a Third Temple in Jerusalem was probably intended to harm Christianity rather than please Jews.[6] Julian also forbade the Christians from teaching and learning classical texts.[12]

Life

Early life

Flavius Claudius Julianus was born at Constantinople in 331,[13] the son of Julius Constantius,[14] consul in 335 and half-brother of the emperor Constantine, by his second wife, Basilina, a woman of Greek origin.[15][16] Both of his parents were Christians. Julian's paternal grandparents were the emperor Constantius Chlorus and his second wife, Flavia Maximiana Theodora. His maternal grandfather was Julius Julianus, Praetorian Prefect of the East under the emperor Licinius from 315 to 324, and consul suffectus in 325.[17] The name of Julian's maternal grandmother is unknown.

In the turmoil after the death of Constantine in 337, in order to establish himself and his brothers, Julian's zealous Arian cousin Constantius II appears to have led a massacre of most of Julian's close relatives. Constantius II allegedly ordered the murders of many descendants from the second marriage of Constantius Chlorus and Theodora, leaving only Constantius and his brothers Constantine II and Constans I, and their cousins, Julian and Constantius Gallus (Julian's half-brother), as the surviving males related to Emperor Constantine. Constantius II, Constans I, and Constantine II were proclaimed joint emperors, each ruling a portion of Roman territory. Julian and Gallus were excluded from public life, were strictly guarded in their youth, and given a Christian education. They were likely saved by their youth and at the urging of the Empress Eusebia. If Julian's later writings are to be believed, Constantius would later be tormented with guilt at the massacre of 337.

Initially growing up in Bithynia, raised by his maternal grandmother, at the age of seven Julian was under the guardianship of Eusebius, the semi-Arian Christian Bishop of Nicomedia, and taught by Mardonius, a Gothic eunuch, about whom he later wrote warmly. After Eusebius died in 342, both Julian and Gallus were exiled to the imperial estate of Macellum in Cappadocia. Here Julian met the Christian bishop George of Cappadocia, who lent him books from the classical tradition. At the age of 18, the exile was lifted and he dwelt briefly in Constantinople and Nicomedia.[18] He became a lector, a minor office in the Christian church, and his later writings show a detailed knowledge of the Bible, likely acquired in his early life.[19]

Julian's conversion from Christianity to paganism happened at around the age of 20. Looking back on his life in 362, Julian wrote that he had spent twenty years in the way of Christianity and twelve in the true way, i.e., the way of Helios.[20] Julian began his study of Neoplatonism in Asia Minor in 351, at first under Aedesius, the philosopher, and then Aedesius' student Eusebius of Myndus. It was from Eusebius that Julian learned of the teachings of Maximus of Ephesus, whom Eusebius criticized for his more mystical form of Neoplatonic theurgy. Eusebius related his meeting with Maximus, in which the theurgist invited him into the temple of Hecate and, chanting a hymn, caused a statue of the goddess to smile and laugh, and her torches to ignite. Eusebius reportedly told Julian that he "must not marvel at any of these things, even as I marvel not, but rather believe that the thing of the highest importance is that purification of the soul which is attained by reason." In spite of Eusebius' warnings regarding the "impostures of witchcraft and magic that cheat the senses" and "the works of conjurers who are insane men led astray into the exercise of earthly and material powers", Julian was intrigued, and sought out Maximus as his new mentor. According to the historian Eunapius, when Julian left Eusebius, he told his former teacher "farewell, and devote yourself to your books. You have shown me the man I was in search of."[21]

Constantine II died in 340 when he attacked his brother Constans. Constans in turn fell in 350 in the war against the usurper Magnentius. This left Constantius II as the sole remaining emperor. In need of support, in 351 he made Julian's half-brother, Gallus, caesar of the East, while Constantius II himself turned his attention westward to Magnentius, whom he defeated decisively that year. In 354 Gallus, who had imposed a rule of terror over the territories under his command, was executed. Julian was summoned to Constantius' court in Mediolanum (Milan) in 354, and held for a year, under suspicion of treasonable intrigue, first with his brother and then with Claudius Silvanus; he was cleared, in part because Empress Eusebia intervened on his behalf, and he was permitted to study in Athens (Julian expresses his gratitude to the empress in his third oration).[22] While there, Julian became acquainted with two men who later became both bishops and saints: Gregory of Nazianzus and Basil the Great. In the same period, Julian was also initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries, which he would later try to restore.

Caesar in Gaul

After dealing with the rebellions of Magnentius and Silvanus, Constantius felt he needed a permanent representative in Gaul. In 355, Julian was summoned to appear before the emperor in Mediolanum and on 6 November was made caesar of the West, marrying Constantius' sister, Helena. Constantius, after his experience with Gallus, intended his representative to be more a figurehead than an active participant in events, so he packed Julian off to Gaul with a small retinue, assuming his prefects in Gaul would keep Julian in check. At first reluctant to trade his scholarly life for war and politics, Julian eventually took every opportunity to involve himself in the affairs of Gaul.[23] In the following years he learned how to lead and then run an army, through a series of campaigns against the Germanic tribes that had settled on both sides of the Rhine.

Campaigns against Germanic kingdoms

During his first campaign in 356, Julian led an army to the Rhine, where he engaged the inhabitants and recovered several towns that had fallen into Frankish hands, including Colonia Agrippina (Cologne). With success under his belt he withdrew for the winter to Gaul, distributing his forces to protect various towns, and choosing the small town of Senon near Verdun to await the spring.[24] This turned out to be a tactical error, for he was left with insufficient forces to defend himself when a large contingent of Franks besieged the town and Julian was virtually held captive there for several months, until his general Marcellus deigned to lift the siege. Relations between Julian and Marcellus seem to have been poor. Constantius accepted Julian's report of events and Marcellus was replaced as magister equitum by Severus.[25][26]

The following year saw a combined operation planned by Constantius to regain control of the Rhine from the Germanic peoples who had spilt across the river onto the west bank. From the south his magister peditum Barbatio was to come from Milan and amass forces at Augst (near the Rhine bend), then set off north with 25,000 soldiers; Julian with 13,000 troops would move east from Durocortorum (Rheims). However, while Julian was in transit, a group of Laeti attacked Lugdunum (Lyon) and Julian was delayed in order to deal with them. This left Barbatio unsupported and deep in Alamanni territory, so he felt obliged to withdraw, retracing his steps. Thus ended the coördinated operation against the Germanic peoples.[27][28]

With Barbatio safely out of the picture, King Chnodomarius led a confederation of Alamanni forces against Julian and Severus at the Battle of Argentoratum. The Romans were heavily outnumbered[lower-roman 2] and during the heat of battle a group of 600 horsemen on the right wing deserted,[29] yet, taking full advantage of the limitations of the terrain, the Romans were overwhelmingly victorious. The enemy was routed and driven into the river. King Chnodomarius was captured and later sent to Constantius in Milan.[30][31] Ammianus, who was a participant in the battle, portrays Julian in charge of events on the battlefield[32] and describes how the soldiers, because of this success, acclaimed Julian attempting to make him Augustus, an acclamation he rejected, rebuking them. He later rewarded them for their valor.[33]

Rather than chase the routed enemy across the Rhine, Julian now proceeded to follow the Rhine north, the route he followed the previous year on his way back to Gaul. At Moguntiacum (Mainz), however, he crossed the Rhine in an expedition that penetrated deep into what is today Germany, and forced three local kingdoms to submit. This action showed the Alamanni that Rome was once again present and active in the area. On his way back to winter quarters in Paris he dealt with a band of Franks who had taken control of some abandoned forts along the Meuse River.[31][34]

In 358, Julian gained victories over the Salian Franks on the Lower Rhine, settling them in Toxandria in the Roman Empire, north of today's city of Tongeren, and over the Chamavi, who were expelled back to Hamaland.

Taxation and administration

At the end of 357 Julian, with the prestige of his victory over the Alamanni to give him confidence, prevented a tax increase by the Gallic praetorian prefect Florentius and personally took charge of the province of Belgica Secunda. This was Julian's first experience with civil administration, where his views were influenced by his liberal education in Greece. Properly it was a role that belonged to the praetorian prefect. However, Florentius and Julian often clashed over the administration of Gaul. Julian's first priority, as caesar and nominal ranking commander in Gaul, was to drive out the barbarians who had breached the Rhine frontier. However, he sought to win over the support of the civil population, which was necessary for his operations in Gaul and also to show his largely Germanic army the benefits of Imperial rule. He therefore felt it was necessary to rebuild stable and peaceful conditions in the devastated cities and countryside. For this reason, Julian clashed with Florentius over the latter's support of tax increases, as mentioned above, and Florentius's own corruption in the bureaucracy.

Constantius attempted to maintain some modicum of control over his caesar, which explains his removal of Julian's close adviser Saturninius Secundus Salutius from Gaul. His departure stimulated the writing of Julian's oration, "Consolation Upon the Departure of Salutius".[35]

Rebellion in Paris

In the fourth year of Julian's stay in Gaul, the Sassanid emperor, Shapur II, invaded Mesopotamia and took the city of Amida after a 73-day siege. In February 360, Constantius II ordered more than half of Julian's Gallic troops to join his eastern army, the order by-passing Julian and going directly to the military commanders. Although Julian at first attempted to expedite the order, it provoked an insurrection by troops of the Petulantes, who had no desire to leave Gaul. According to the historian Zosimus, the army officers were those responsible for distributing an anonymous tract[36] expressing complaints against Constantius as well as fearing for Julian's ultimate fate. Notably absent at the time was the prefect Florentius, who was seldom far from Julian's side, though now he was kept busy organizing supplies in Vienne and away from any strife that the order could cause. Julian would later blame him for the arrival of the order from Constantius.[37] Ammianus Marcellinus even suggested that the fear of Julian gaining more popularity than himself caused Constantius to send the order on the urging of Florentius.[38]

The troops proclaimed Julian Augustus in Paris, and this in turn led to a very swift military effort to secure or win the allegiance of others. Although the full details are unclear, there is evidence to suggest that Julian may have at least partially stimulated the insurrection. If so, he went back to business as usual in Gaul, for, from June to August of that year, Julian led a successful campaign against the Attuarian Franks.[39][40] In November, Julian began openly using the title Augustus, even issuing coins with the title, sometimes with Constantius, sometimes without. He celebrated his fifth year in Gaul with a big show of games.[41]

In the spring of 361, Julian led his army into the territory of the Alamanni, where he captured their king, Vadomarius. Julian claimed that Vadomarius had been in league with Constantius, encouraging him to raid the borders of Raetia.[42] Julian then divided his forces, sending one column to Raetia, one to northern Italy and the third he led down the Danube on boats. His forces claimed control of Illyricum and his general, Nevitta, secured the pass of Succi into Thrace. He was now well out of his comfort zone and on the road to civil war.[43] (Julian would state in late November that he set off down this road "because, having been declared a public enemy, I meant to frighten him [Constantius] merely, and that our quarrel should result in intercourse on more friendly terms..."[44])

However, in June, forces loyal to Constantius captured the city of Aquileia on the north Adriatic coast, an event that threatened to cut Julian off from the rest of his forces, while Constantius's troops marched towards him from the east. Aquileia was subsequently besieged by 23,000 men loyal to Julian.[45] All Julian could do was sit it out in Naissus, the city of Constantine's birth, waiting for news and writing letters to various cities in Greece justifying his actions (of which only the letter to the Athenians has survived in its entirety).[46] Civil war was avoided only by the death on November 3 of Constantius, who, in his last will, is alleged by some sources to have recognized Julian as his rightful successor.

Empire and administration

On December 11, 361, Julian entered Constantinople as sole emperor and, despite his rejection of Christianity, his first political act was to preside over Constantius' Christian burial, escorting the body to the Church of the Apostles, where it was placed alongside that of Constantine.[46] This act was a demonstration of his lawful right to the throne.[47] He is also now thought to have been responsible for the building of Santa Costanza on a Christian site just outside Rome as a mausoleum for his wife Helena and sister-in-law Constantina.[48]

The new Emperor rejected the style of administration of his immediate predecessors. He blamed Constantine for the state of the administration and for having abandoned the traditions of the past. He made no attempt to restore the tetrarchal system begun under Diocletian. Nor did he seek to rule as an absolute autocrat. His own philosophic notions led him to idealize the reigns of Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius. In his first panegyric to Constantius, Julian described the ideal ruler as being essentially primus inter pares ("first among equals"), operating under the same laws as his subjects. While in Constantinople, therefore, it was not strange to see Julian frequently active in the Senate, participating in debates and making speeches, placing himself at the level of the other members of the Senate.[49]

He viewed the royal court of his predecessors as inefficient, corrupt and expensive. Thousands of servants, eunuchs and superfluous officials were therefore summarily dismissed. He set up the Chalcedon tribunal to deal with the corruption of the previous administration under the supervision of Magister Militum Arbitio. Several high-ranking officials under Constantius, including the chamberlain Eusebius, were found guilty and executed. (Julian was conspicuously absent from the proceedings, perhaps signaling his displeasure at their necessity.)[50] He continually sought to reduce what he saw as a burdensome and corrupt bureaucracy within the Imperial administration whether it involved civic officials, secret agents or the imperial postal service.

Another effect of Julian's political philosophy was that the authority of the cities was expanded at the expense of the imperial bureaucracy as Julian sought to reduce direct imperial involvement in urban affairs. For example, city land owned by the imperial government was returned to the cities, city council members were compelled to resume civic authority, often against their will, and the tribute in gold by the cities called the aurum coronarium was made voluntary rather than a compulsory tax. Additionally, arrears of land taxes were cancelled.[51] This was a key reform reducing the power of corrupt imperial officials, as the unpaid taxes on land were often hard to calculate or higher than the value of the land itself. Forgiving back taxes both made Julian more popular and allowed him to increase collections of current taxes.

While he ceded much of the authority of the imperial government to the cities, Julian also took more direct control himself. For example, new taxes and corvées had to be approved by him directly rather than left to the judgment of the bureaucratic apparatus. Julian certainly had a clear idea of what he wanted Roman society to be, both in political as well as religious terms. The terrible and violent dislocation of the 3rd century meant that the Eastern Mediterranean had become the economic locus of the Empire. If the cities were treated as relatively autonomous local administrative areas, it would simplify the problems of imperial administration, which as far as Julian was concerned, should be focused on the administration of the law and defense of the empire's vast frontiers.

In replacing Constantius's political and civil appointees, Julian drew heavily from the intellectual and professional classes, or kept reliable holdovers, such as the rhetorician Themistius. His choice of consuls for the year 362 was more controversial. One was the very acceptable Claudius Mamertinus, previously the Praetorian prefect of Illyricum. The other, more surprising choice was Nevitta, Julian's trusted Frankish general. This latter appointment made overt the fact that an emperor's authority depended on the power of the army. Julian's choice of Nevitta appears to have been aimed at maintaining the support of the Western army which had acclaimed him.

Clash with the Antiochenes

After five months of dealings at the capital, Julian left Constantinople in May and moved to Antioch, arriving in mid-July and staying there for nine months before launching his fateful campaign against Persia in March 363. Antioch was a city favored by splendid temples along with a famous oracle of Apollo in nearby Daphne, which may have been one reason for his choosing to reside there. It had also been used in the past as a staging place for amassing troops, a purpose which Julian intended to follow.[52]

His arrival on 18 July was well received by the Antiochenes, though it coincided with the celebration of the Adonia, a festival which marked the death of Adonis, so there was wailing and moaning in the streets—not a good omen for an arrival.[53][54]

Julian soon discovered that wealthy merchants were causing food problems, apparently by hoarding food and selling it at high prices. He hoped that the curia would deal with the issue for the situation was headed for a famine. When the curia did nothing, he spoke to the city's leading citizens, trying to persuade them to take action. Thinking that they would do the job, he turned his attention to religious matters.[54]

He tried to resurrect the ancient oracular spring of Castalia at the temple of Apollo at Daphne. After being advised that the bones of 3rd-century bishop Babylas were suppressing the god, he made a public-relations mistake in ordering the removal of the bones from the vicinity of the temple. The result was a massive Christian procession. Shortly after that, when the temple was destroyed by fire, Julian suspected the Christians and ordered stricter investigations than usual. He also shut up the chief Christian church of the city, before the investigations proved that the fire was the result of an accident.[55][56]

When the curia still took no substantial action in regards to the food shortage, Julian intervened, fixing the prices for grain and importing more from Egypt. Then landholders refused to sell theirs, claiming that the harvest was so bad that they had to be compensated with fair prices. Julian accused them of price gouging and forced them to sell. Various parts of Libanius' orations may suggest that both sides were justified to some extent[57][58] while Ammianus blames Julian for "a mere thirst for popularity".[59]

Julian's ascetic lifestyle was not popular either, since his subjects were accustomed to the idea of an all-powerful Emperor who placed himself well above them. Nor did he improve his dignity with his own participation in the ceremonial of bloody sacrifices.[60] David S. Potter, an assistant secretary of the US Navy, said after nearly two millennia:

They expected a man who was both removed from them by the awesome spectacle of imperial power, and would validate their interests and desires by sharing them from his Olympian height (...) He was supposed to be interested in what interested his people, and he was supposed to be dignified. He was not supposed to leap up and show his appreciation for a panegyric that it was delivered, as Julian had done on January 3, when Libanius was speaking, and ignore the chariot races.[61]

He then tried to address public criticism and mocking of him by issuing a satire ostensibly on himself, called Misopogon or "Beard Hater". There he blames the people of Antioch for preferring that their ruler have his virtues in the face rather than in the soul.

Even Julian's intellectual friends and fellow pagans were of a divided mind about this habit of talking to his subjects on an equal footing: Ammianus Marcellinus saw in that only the foolish vanity of someone "excessively anxious for empty distinction", whose "desire for popularity often led him to converse with unworthy persons".[62]

On leaving Antioch he appointed Alexander of Heliopolis as governor, a violent and cruel man whom the Antiochene Libanius, a friend of the emperor, admits on first thought was a "dishonourable" appointment. Julian himself described the man as "undeserving" of the position, but appropriate "for the avaricious and rebellious people of Antioch".[63]

Persian campaign

Julian's rise to Augustus was the result of military insurrection eased by Constantius's sudden death. This meant that, while he could count on the wholehearted support of the Western army which had aided his rise, the Eastern army was an unknown quantity originally loyal to the Emperor he had risen against, and he had tried to woo it through the Chalcedon tribunal. However, to solidify his position in the eyes of the eastern army, he needed to lead its soldiers to victory and a campaign against the Sassanid Persians offered such an opportunity.

An audacious plan was formulated whose goal was to lay siege on the Sassanid capital city of Ctesiphon and definitively secure the eastern border. Yet the full motivation for this ambitious operation is, at best, unclear. There was no direct necessity for an invasion, as the Sassanids sent envoys in the hope of settling matters peacefully. Julian rejected this offer.[64] Ammianus states that Julian longed for revenge on the Persians and that a certain desire for combat and glory also played a role in his decision to go to war.[65]

Into enemy territory

On 5 March 363, despite a series of omens against the campaign, Julian departed from Antioch with about 65,000–83,000,[66][67] or 80,000–90,000 men[68] (the traditional number accepted by Gibbon[69] is 95,000 effectives total), and headed north toward the Euphrates. En route he was met by embassies from various small powers offering assistance, none of which he accepted. He did order the Armenian King Arsaces to muster an army and await instructions.[70] He crossed the Euphrates near Hierapolis and moved eastward to Carrhae, giving the impression that his chosen route into Persian territory was down the Tigris.[71] For this reason it seems he sent a force of 30,000 soldiers under Procopius and Sebastianus further eastward to devastate Media in conjunction with Armenian forces.[72] This was where two earlier Roman campaigns had concentrated and where the main Persian forces were soon directed.[73] Julian's strategy lay elsewhere, however. He had had a fleet built of over 1,000 ships at Samosata in order to supply his army for a march down the Euphrates and of 50 pontoon ships to facilitate river crossings. Procopius and the Armenians would march down the Tigris to meet Julian near Ctesiphon.[72] Julian's ultimate aim seems to have been "regime change" by replacing king Shapur II with his brother Hormisdas.[73][74]

After feigning a march further eastward, Julian's army turned south to Circesium at the confluence of the Abora (Khabur) and the Euphrates arriving at the beginning of April.[72] Passing Dura on April 6, the army made good progress, bypassing towns after negotiations or besieging those which chose to oppose him. At the end of April the Romans captured the fortress of Pirisabora, which guarded the canal approach from the Euphrates to Ctesiphon on the Tigris.[75] As the army marched toward the Persian capital, the Sassanids broke the dikes which crossed the land, turning it into marshland, slowing the progress of the Roman army.[76]

Ctesiphon

By mid-May, the army had reached the vicinity of the heavily fortified Persian capital, Ctesiphon, where Julian partially unloaded some of the fleet and had his troops ferried across the Tigris by night.[77] The Romans gained a tactical victory over the Persians before the gates of the city, driving them back into the city.[78] However, the Persian capital was not taken, the main Persian army was still at large and approaching, while the Romans lacked a clear strategic objective.[79] In the council of war which followed, Julian's generals persuaded him not to mount a siege against the city, given the impregnability of its defenses and the fact that Shapur would soon arrive with a large force.[80] Julian, not wanting to give up what he had gained and probably still hoping for the arrival of the column under Procopius and Sebastianus, set off east into the Persian interior, ordering the destruction of the fleet.[78] This proved to be a hasty decision, for they were on the wrong side of the Tigris with no clear means of retreat and the Persians had begun to harass them from a distance, burning any food in the Romans' path. Julian had not brought adequate siege equipment, so there was nothing he could do when he found that the Persians had flooded the area behind him, forcing him to withdraw.[81] A second council of war on 16 June 363 decided that the best course of action was to lead the army back to the safety of Roman borders, not through Mesopotamia, but northward to Corduene.[82][83]

Death

During the withdrawal, Julian's forces suffered several attacks from Sassanid forces.[83] In one such engagement on 26 June 363, the indecisive Battle of Samarra near Maranga, Julian was wounded when the Sassanid army raided his column. In the haste of pursuing the retreating enemy, Julian chose speed rather than caution, taking only his sword and leaving his coat of mail.[84] He received a wound from a spear that reportedly pierced the lower lobe of his liver, the peritoneum and intestines. The wound was not immediately deadly. Julian was treated by his personal physician, Oribasius of Pergamum, who seems to have made every attempt to treat the wound. This probably included the irrigation of the wound with a dark wine, and a procedure known as gastrorrhaphy, the suturing of the damaged intestine. On the third day a major hemorrhage occurred and the emperor died during the night.[85][lower-roman 3] As Julian wished, his body was buried outside Tarsus, though it was later removed to Constantinople.[86]

In 364, Libanius stated that Julian was assassinated by a Christian who was one of his own soldiers;[87] this charge is not corroborated by Ammianus Marcellinus or other contemporary historians. John Malalas reports that the supposed assassination was commanded by Basil of Caesarea.[88] Fourteen years later, Libanius said that Julian was killed by a Saracen (Lakhmid) and this may have been confirmed by Julian's doctor Oribasius who, having examined the wound, said that it was from a spear used by a group of Lakhmid auxiliaries in Persian service.[89] Later Christian historians propagated the tradition that Julian was killed by Saint Mercurius.[90] Julian was succeeded by the short-lived Emperor Jovian who reestablished Christianity's privileged position throughout the Empire.

Libanius says in his epitaph of the deceased emperor (18.304) that "I have mentioned representations (of Julian); many cities have set him beside the images of the gods and honour him as they do the gods. Already a blessing has been besought of him in prayer, and it was not in vain. To such an extent has he literally ascended to the gods and received a share of their power from him themselves." However, no similar action was taken by the Roman central government, which would be more and more dominated by Christians in the ensuing decades.

Considered apocryphal is the report that his dying words were νενίκηκάς με, Γαλιλαῖε, or Vicisti, Galilaee ("You have won, Galilean"),[lower-roman 4] supposedly expressing his recognition that, with his death, Christianity would become the Empire's state religion. The phrase introduces the 1866 poem Hymn to Proserpine, which was Algernon Charles Swinburne's elaboration of what a philosophic pagan might have felt at the triumph of Christianity. It also ends the Polish Romantic play The Undivine comedy written in 1833 by Zygmunt Krasiński.

Tomb

As he had requested,[92] Julian's body was buried in Tarsus. It lay in a tomb outside the city, across a road from that of Maximinus Daia.[93]

However, chronicler Zonaras says that at some "later" date his body was exhumed and reburied in or near the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, where Constantine and the rest of his family lay.[94] His sarcophagus is listed as standing in a "stoa" there by Constantine Porphyrogenitus.[95] The church was demolished by the Ottoman Turks after the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Today a sarcophagus of porphyry, believed by Jean Ebersolt to be Julian's, stands in the grounds of the Archaeological Museum in Istanbul.[96]

Religious issues

Beliefs

Julian's personal religion was both pagan and philosophical; he viewed the traditional myths as allegories, in which the ancient gods were aspects of a philosophical divinity. The chief surviving sources are his works To King Helios and To the Mother of the Gods, which were written as panegyrics, not theological treatises.[14]

As the last pagan ruler of the Roman Empire, Julian's beliefs are of great interest for historians, but they are not in complete agreement. He learned theurgy from Maximus of Ephesus, a student of Iamblichus;[97] his system bears some resemblance to the Neoplatonism of Plotinus; Polymnia Athanassiadi has brought new attention to his relations with Mithraism, although whether he was initiated into it remains debatable; and certain aspects of his thought (such as his reorganization of paganism under High Priests, and his fundamental monotheism) may show Christian influence. Some of these potential sources have not come down to us, and all of them influenced each other, which adds to the difficulties.[98]

According to one theory (that of Glen Bowersock in particular), Julian's paganism was highly eccentric and atypical because it was heavily influenced by an esoteric approach to Platonic philosophy sometimes identified as theurgy and also Neoplatonism. Others (Rowland Smith, in particular) have argued that Julian's philosophical perspective was nothing unusual for a "cultured" pagan of his time, and, at any rate, that Julian's paganism was not limited to philosophy alone, and that he was deeply devoted to the same gods and goddesses as other pagans of his day.

Because of his Neoplatonist background Julian accepted the creation of humanity as described in Plato's Timaeus. Julian writes, "when Zeus was setting all things in order there fell from him drops of sacred blood, and from them, as they say, arose the race of men."[99] Further he writes, "they who had the power to create one man and one woman only, were able to create many men and women at once..."[100] His view contrasts with the Christian belief that humanity is derived from the one pair, Adam and Eve. Elsewhere he argues against the single pair origin, indicating his disbelief, noting for example, "how very different in their bodies are the Germans and Scythians from the Libyans and Ethiopians."[101][102]

The Christian historian Socrates Scholasticus was of the opinion that Julian believed himself to be Alexander the Great "in another body" via transmigration of souls, "in accordance with the teachings of Pythagoras and Plato".[103]

The diet of Julian is said to have been predominantly vegetable-based.[104]

Restoration of state paganism

After gaining the purple, Julian started a religious reformation of the empire, which was intended to restore the lost strength of the Roman state. He supported the restoration of Hellenistic polytheism as the state religion. His laws tended to target wealthy and educated Christians, and his aim was not to destroy Christianity but to drive the religion out of "the governing classes of the empire — much as Chinese Buddhism was driven back into the lower classes by a revived Confucian mandarinate in 13th century China."[105]

He restored pagan temples which had been confiscated since Constantine's time, or simply appropriated by wealthy citizens; he repealed the stipends that Constantine had awarded to Christian bishops, and removed their other privileges, including a right to be consulted on appointments and to act as private courts. He also reversed some favors that had previously been given to Christians. For example, he reversed Constantine's declaration that Majuma, the port of Gaza, was a separate city. Majuma had a large Christian congregation while Gaza was still predominantly pagan.

On 4 February 362, Julian promulgated an edict to guarantee freedom of religion. This edict proclaimed that all the religions were equal before the law, and that the Roman Empire had to return to its original religious eclecticism, according to which the Roman state did not impose any religion on its provinces. The edict was seen as an act of favor toward the Jews, in order to upset the Christians.

Since the persecution of Christians by past Roman Emperors had seemingly only strengthened Christianity, many of Julian's actions were designed to harass Christians and undermine their ability to organize resistance to the re-establishment of paganism in the empire.[106] Julian's preference for a non-Christian and non-philosophical view of Iamblichus' theurgy seems to have convinced him that it was right to outlaw the practice of the Christian view of theurgy and demand the suppression of the Christian set of Mysteries.[107]

In his School Edict Julian required that all public teachers be approved by the Emperor; the state paid or supplemented much of their salaries. Ammianus Marcellinus explains this as intending to prevent Christian teachers from using pagan texts (such as the Iliad, which was widely regarded as divinely inspired) that formed the core of classical education: "If they want to learn literature, they have Luke and Mark: Let them go back to their churches and expound on them", the edict says.[105] This was an attempt to remove some of the influence of the Christian schools which at that time and later used ancient Greek literature in their teachings in their effort to present the Christian religion as being superior to paganism. The edict also dealt a severe financial blow to many Christian scholars, tutors and teachers, as it deprived them of students.

In his Tolerance Edict of 362, Julian decreed the reopening of pagan temples, the restitution of confiscated temple properties, and the return from exile of dissident Christian bishops. The latter was an instance of tolerance of different religious views, but it may also have been an attempt by Julian to foster schisms and divisions between different Christian sects, since conflict between rival Christian sects was quite fierce.[108]

His care in the institution of a pagan hierarchy in opposition to that of the Christians was due to his wish to create a society in which every aspect of the life of the citizens was to be connected, through layers of intermediate levels, to the consolidated figure of the Emperor — the final provider for all the needs of his people. Within this project, there was no place for a parallel institution, such as the Christian hierarchy or Christian charity.[109]

Paganism's shift under Julian

Julian's popularity among the people and the army during his brief reign suggest that he might have brought paganism back to the fore of Roman public and private life.[110] In fact, during his lifetime, neither pagan nor Christian ideology reigned supreme, and the greatest thinkers of the day argued about the merits and rationality of each religion.[111] Most importantly for the pagan cause, though, Rome was still a predominantly pagan empire that had not wholly accepted Christianity.[112]

Even so, Julian's short reign did not stem the tide of Christianity. The emperor's ultimate failure can arguably be attributed to the manifold religious traditions and deities that paganism promulgated. Most pagans sought religious affiliations that were unique to their culture and people, and they had internal divisions that prevented them from creating any one ‘pagan religion.’ Indeed, the term pagan was simply a convenient appellation for Christians to lump together the believers of a system they opposed.[113] In truth, there was no Roman religion, as modern observers would recognize it.[114] Instead, paganism came from a system of observances that one historian has characterized as “no more than a spongy mass of tolerance and tradition.”[114]

This system of tradition had already shifted dramatically by the time Julian came to power; gone were the days of massive sacrifices honoring the gods. The communal festivals that involved sacrifice and feasting, which once united communities, now tore them apart—Christian against pagan.[115] Civic leaders did not even have the funds, much less the support, to hold religious festivals. Julian found the financial base that had supported these ventures (sacred temple funds) had been seized by his uncle Constantine to support the Christian Church.[116] In all, Julian's short reign simply could not shift the feeling of inertia that had swept across the Empire. Christians had denounced sacrifice, stripped temples of their funds, and cut priests and magistrates off from the social prestige and financial benefits accompanying leading pagan positions in the past. Leading politicians and civic leaders had little motivation to rock the boat by reviving pagan festivals. Instead, they chose to adopt the middle ground by having ceremonies and mass entertainment that were religiously neutral.[117]

After witnessing the reign of two emperors bent on supporting the Church and stamping out paganism, it is understandable that pagans simply did not embrace Julian's idea of proclaiming their devotion to polytheism and their rejection of Christianity. Many chose to adopt a practical approach and not support Julian's public reforms actively for fear of a Christian revival. However, this apathetic attitude forced the emperor to shift central aspects of pagan worship. Julian's attempts to reinvigorate the people shifted the focus of paganism from a system of tradition to a religion with some of the same characteristics that he opposed in Christianity.[118] For example, Julian attempted to introduce a tighter organization for the priesthood, with greater qualifications of character and service. Classical paganism simply did not accept this idea of priests as model citizens. Priests were elites with social prestige and financial power who organized festivals and helped pay for them.[116] Yet Julian's attempt to impose moral strictness on the civic position of priesthood only made paganism more in tune with Christian morality, drawing it further from paganism's system of tradition.

Indeed, this development of a pagan order created the foundations of a bridge of reconciliation over which paganism and Christianity could meet.[119] Likewise, Julian's persecution of Christians, who by pagan standards were simply part of a different cult, was quite an un-pagan attitude that transformed paganism into a religion that accepted only one form of religious experience while excluding all others—such as Christianity.[120] In trying to compete with Christianity in this manner, Julian fundamentally changed the nature of pagan worship. That is, he made paganism a religion, whereas it once had been only a system of tradition.

Juventinus and Maximus

Despite this inadvertent reconciliation of paganism to Christianity, however, many of the Church fathers viewed the emperor with hostility, and told stories of his supposed wickedness after his death. A sermon by Saint John Chrysostom, entitled On Saints Juventinus and Maximinus, tells the story of two of Julian's soldiers at Antioch, who were overheard at a drinking party, criticizing the emperor's religious policies, and taken into custody. According to John, the emperor had made a deliberate effort to avoid creating martyrs of those who disagreed with his reforms; but Juventinus and Maximinus admitted to being Christians, and refused to moderate their stance. John asserts that the emperor forbade anyone from having contact with the men, but that nobody obeyed his orders; so he had the two men executed in the middle of the night. John urges his audience to visit the tomb of these martyrs.[121]

Charity

The fact that Christian charities were open to all, including pagans, put this aspect of Roman citizens' lives out of the control of Imperial authority and under that of the Church. Thus Julian envisioned the institution of a Roman philanthropic system, and cared for the behaviour and the morality of the pagan priests, in the hope that it would mitigate the reliance of pagans on Christian charity, saying: "These impious Galileans not only feed their own poor, but ours also; welcoming them into their agapae, they attract them, as children are attracted, with cakes."[122]

Attempt to rebuild the Jewish Temple

In 363, not long before Julian left Antioch to launch his campaign against Persia, in keeping with his effort to oppose Christianity, he allowed Jews to rebuild their Temple.[123][124][125] The point was that the rebuilding of the Temple would invalidate Jesus’ prophecy about its destruction in 70, which Christians had cited as proof of Jesus' truth.[123] But fires broke out and stopped the project.[126] A personal friend of his, Ammianus Marcellinus, wrote this about the effort:

Julian thought to rebuild at an extravagant expense the proud Temple once at Jerusalem, and committed this task to Alypius of Antioch. Alypius set vigorously to work, and was seconded by the governor of the province; when fearful balls of fire, breaking out near the foundations, continued their attacks, till the workmen, after repeated scorchings, could approach no more: and he gave up the attempt.

The failure to rebuild the Temple has been ascribed to the Galilee earthquake of 363. Although there is contemporary testimony for the miracle, in the Orations of St. Gregory Nazianzen, this may be taken to be unreliable.[127] Other possibilities are accidental fire or deliberate sabotage. Divine intervention was for centuries a common view among Christian historians,[128] and it was seen as proof of Jesus’ divinity.[123]

Julian's support of Jews caused Jews to call him "Julian the Hellene".[129]

Works

Julian wrote several works in Greek, some of which have come down to us.

| Budé | Date | Work | Comment | Wright |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 356/7[130] | Panegyric In Honour Of Constantius | Written to reassure Constantius that he was on his side. | I |

| II | ~June 357[130] | Panegyric In Honour Of Eusebia | Expresses gratitude for Eusebia's support. | III |

| III | 357/8[131] | The Heroic Deeds Of Constantius | Indicates his support of Constantius, while being critical. (Sometimes called "second panegyric to Constantius".) | II |

| IV | 359[35] | Consolation Upon the Departure of Salutius[132] | Grapples with the removal of his close advisor in Gaul. | VIII |

| V | 361[133] | Letter To The Senate And People of Athens | An attempt to explain the actions leading up to his rebellion. | – |

| VI | early 362[134] | Letter To Themistius The Philosopher | Response to an ingratiating letter from Themistius, outlining J.'s political reading | – |

| VII | March 362[135] | To The Cynic Heracleios | Attempt to set Cynics straight regarding their religious responsibilities. | VII |

| VIII | ~March 362[136] | Hymn To The Mother Of The Gods | A defense of Hellenism and Roman tradition. | V |

| IX | ~May 362[137] | To the Uneducated Cynics | Another attack on Cynics who he thought didn't follow the principles of Cynicism. | VI |

| X | December 362[138] | The Caesars[139] | Satire describing a competition among Roman emperors as to who was the best. Strongly critical of Constantine. | – |

| XI | December 362[140] | Hymn To King Helios | Attempt to describe the Roman religion as seen by Julian. | IV |

| XII | early 363[141] | Misopogon, Or, Beard-Hater | Written as a satire on himself, while attacking the people of Antioch for their shortcomings. | – |

| – | 362/3[142] | Against the Galilaeans | Polemic against Christians, which now only survives as fragments. | – |

| – | 362[lower-roman 5] | Fragment Of A Letter To A Priest | Attempt to counteract the aspects that he thought were positive in Christianity. | – |

| – | 359–363 | Letters | Both personal and public letters from much of his career. | – |

| – | ? | Epigrams | Small number of short verse works. | – |

- Budé indicates the numbers used by Athanassiadi given in the Budé edition (1963 & 1964) of Julian's Opera.[lower-roman 6]

- Wright indicates the oration numbers provided in W.C.Wright's edition of Julian's works.

The religious works contain involved philosophical speculations, and the panegyrics to Constantius are formulaic and elaborate in style.

The Misopogon (or "Beard Hater") is a light-hearted account of his clash with the inhabitants of Antioch after he was mocked for his beard and generally scruffy appearance for an Emperor. The Caesars is a humorous tale of a contest among some of the most notable Roman Emperors: Julius Caesar, Augustus, Trajan, Marcus Aurelius, Constantine, and also Alexander the Great. This was a satiric attack upon the recent Constantine, whose worth, both as a Christian and as the leader of the Roman Empire, Julian severely questions.

One of the most important of his lost works is his Against the Galileans, intended to refute the Christian religion. The only parts of this work which survive are those excerpted by Cyril of Alexandria, who gives extracts from the three first books in his refutation of Julian, Contra Julianum. These extracts do not give an adequate idea of the work: Cyril confesses that he had not ventured to copy several of the weightiest arguments.

Problems regarding authenticity

Julian's works have been edited and translated several times since the Renaissance, most often separately; but many are translated in the Loeb Classical Library edition of 1913, edited by Wilmer Cave Wright. Wright mentions, however, that there are many problems surrounding Julian's vast collection of works, mainly the letters ascribed to Julian.[143] The collections of letters we have today are the result of many smaller collections which contained varying numbers of Julian's works in various combinations. For example, in Laurentianus 58.16 the largest collection of letters ascribed to Julian was found, containing 43 manuscripts. it is unclear what the origins of many letters in these collections are.

Joseph Bidez & François Cumont compiled all of these different collections together in 1922 and got a total of 284 items. 157 of these were considered genuine and 127 were regarded spurious. This contrasts starkly with Wright's earlier mentioned collection which contains only 73 items which are considered genuine and 10 apocryphal letter. Michael Trapp notes however that when comparing Bidez & Cumont's work with Wright, they regard as many as sixteen of Wright's genuine letters as spurious.[144] Which works can be ascribed to Julian is thus very much up to debate.

The problems surrounding Julian's collection of works are exacerbated by the fact that Julian was a very motivated writer, which means it is possible that many more letters could have circulated, despite his short reign. Julian himself attests to the large amount of letters he had to write in one of the letters which is likely to be genuine.[145] Julian's religious agenda gave him even more work than the average emperor as he sought to instruct his newly-styled pagan priests and he had to deal with discontent Christian leaders and communities. An example of him instructing his pagan priests is visible in a fragment in the Vossianus MS., inserted in the Letter to Themistius.[146]

Additionally, Julian's hostility towards the Christian faith inspired vicious counteractions by Christian authors as can be seen in Gregory of Nazianzus' invectives against Julian.[147][148] Christians no doubt suppressed some of Julian's works as well.[149] This Christian influence is still visible in Wright's much smaller collection of Julian's letters. She comments on how some letters are suddenly cut off when the contents become hostile towards Christians, believing them to be the result of Christian censoring. Notable examples of this are in the Fragment of a letter to a Priest and the letter to High-Priest Theodorus.[150][151]

In popular culture

Literature

- In 1681 Lord Russell, an outspoken opponent of King Charles II of England and his brother The Duke of York, got his chaplain to write a Life of Julian the Apostate. This work made use of the Roman Emperor's life in order to address contemporary English political and theological debates – specifically, to reply to the conservative arguments of Dr Hickes's sermons, and defend the lawfulness of resistance in extreme cases.

- In 1847, the controversial German theologian David Friedrich Strauss published in Mannheim the pamphlet Der Romantiker auf dem Thron der Cäsaren ("A Romantic on the Throne of the Caesars"), in which Julian was satirised as "an unworldly dreamer, a man who turned nostalgia for the ancients into a way of life and whose eyes were closed to the pressing needs of the present". In fact, this was a veiled criticism of the contemporary King Frederick William IV of Prussia, known for his romantic dreams of restoring the supposed glories of feudal Medieval society.[152]

- Julian's life inspired the play Emperor and Galilean by Henrik Ibsen.

- The late nineteenth century English novelist George Gissing read an English translation of Julian's work in 1891[153]

- Julian's life and reign were the subject of the novel The Death of the Gods (Julian the Apostate) (1895) in the trilogy of historical novels entitled "Christ and Antichrist" (1895–1904) by the Russian Symbolist poet, novelist and literary theoretician Dmitrii S. Merezhkovskii.

- The opera Der Apostat (1924) by the composer and conductor Felix Weingartner is about Julian.

- In 1945 Nikos Kazantzakis authored the tragedy Julian the Apostate in which the emperor is depicted as an existentialist hero committed to a struggle which he knows will be in vain. It was first staged in Paris in 1948.

- Julian was the subject of a novel, Julian (1964), by Gore Vidal, describing his life and times. It is notable for, among other things, its scathing critique of Christianity.

- Julian appeared in Gods and Legions, by Michael Curtis Ford (2002). Julian's tale was told by his closest companion, the Christian saint Caesarius, and accounts for the transition from a Christian philosophy student in Athens to a pagan Roman Augustus of the old nature.

- Julian's letters are an important part of the symbolism of Michel Butor's novel La Modification.

- The fantasy alternate history The Dragon Waiting by John M. Ford, while set in the time of the Wars of the Roses, uses the reign of Julian as its point of divergence. His reign not being cut short, he was successful in disestablishing Christianity and restoring a religiously eclectic societal order which survived the fall of Rome and into the Renaissance. Characters in the novel refer to him as "Julian the Wise".

- The dystopian speculative fiction novel by Robert Charles Wilson, Julian Comstock: A Story of 22nd-Century America, parallels the life of Julian with the title character as the hereditary president of an oligarchic future United States of America who tries to restore science and combat the fundamentalist Christianity that has taken over the country.

Film

- An Italian movie treatment of his life, Giuliano l'Apostata, appeared in 1919.

See also

- Against the Galilaeans

- Peroz-Shapur, the ancient town of Perisabora destroyed by Julian in 363

- Diodorus of Tarsus

- Itineraries of the Roman emperors, 337–361

- List of Byzantine emperors

Notes

- Rarely Julian II. The iteration distinguishes him from Didius Julianus; it does not account for the usurper Sabinus Julianus.[2]

- Ammianus says that there were 35,000 Alamanni, Res Gestae, 16.12.26, though this figure is now thought to be an overestimate – see David S. Potter, p. 501.

- Note that Ammianus Marcellinus (Res Gestae, 25.3.6 & 23) is of the view that Julian died the night of the same day that he was wounded.

- First recorded by Theodoret[91] in the 5th century.

- Not dealt with in Athanassiadi, or dated by Bowersock, but reflects a time when Julian was emperor, and he had other issues to deal with later.

- Julian's Opera, edited by J.Bidez, G.Rochefort, and C.Lacombrade, with French translations of all the principal works except Against the Galilaeans, which is only preserved in citations in a polemic work by Cyril.

References

Citations

- Browning, p. 103.

- David Sear, Roman Coins and Their Values, Volume 5 (London: Spink, 2014), p. 267.

- Grant, Michael (1980). Greek and Latin authors, 800 B.C.–A.D. 1000, Part 1000. H. W. Wilson Co. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-8242-0640-6.

JULIAN THE APOSTATE (Flavins Claudius Julianus), Roman emperor and Greek writer, was born at Constantinople in ad 332 and died in 363.

- Gibbon, Edward. "Chapter 23". The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

- A Companion to Julian the Apostate. Brill. 2020-01-20. ISBN 978-90-04-41631-4.

- "Julian". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- Phang et al. 2016, p. 998.

- "Ancient Rome: The reign of Julian". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- Potter, David (2009). Rome in the Ancient World - From Romulus to Justinian. Thames & Hudson. p. 289. ISBN 978-0500251522.

- Glanville Downey, "Julian the Apostate at Antioch", Church History, Vol. 8, No. 4 (December, 1939), pp. 303–315. See p. 305.

- Athanassiadi, p. 88.

- Potter, David (2009). Rome in the Ancient World - From Romulus to Justinian. Thames & Hudson. p. 288. ISBN 978-0500251522.

- Tougher, 12, citing Bouffartigue: L'Empereur Julien et la culture de son temps p. 30 for the argument for 331; A.H. Jones, J.R. Martindale, and J. Morris "Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Vol. I", p. 447 (Iulianus 29) argues for May or June 332. Bowersock, p. 22, wrote that the month attribution originated in an error and considers that the weight of evidence points to 331, against 332.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 548.

- Norwich, John Julius (1989). Byzantium: the early centuries. Knopf. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-394-53778-8.

Julius Constantius...Constantine had invited him, with his second wife and his young family, to take up residence in his new capital; and it was in Constantinople that his third son Julian was born, in May or June of the year 332. The baby's mother, Basilina, a Greek from Asia Minor, died a few weeks later...

- Bradbury, Jim (2004). The Routledge companion to medieval warfare. Routledge. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-415-22126-9.

JULIAN THE APOSTATE, FLAVIUS CLAUDIUS JULIANUS, ROMAN EMPEROR (332–63) Emperor from 361, son of Julius Constantius and a Greek mother Basilina, grandson of Constantius Chlorus, the only pagan Byzantine Emperor.

- Jones, Martindale, and Morris (1971) Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire volume 1, pp. 148, 478–479. Cambridge.

- Cambridge Ancient History, v. 13, pp. 44–45.

- Boardman, p. 44, citing Julian to the Alexandrians, Wright's letter 47, of November or December 362. Ezekiel Spanheim 434D. Twelve would be literal, but Julian is counting inclusively.

- Julian. "Letter 47: To the Alexandrians", translated by Emily Wilmer Cave Wright, v. 3, p. 149.

The full text of Letters of Julian/Letter 47 at Wikisource

The full text of Letters of Julian/Letter 47 at Wikisource - "Maximus Lives of the Philosophers and Sophists (English translation)". www.tertullian.org. 1921. pp. 343–565. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- R. Browning, The Emperor Julian (London, 1975), pp. 74–75. However, Shaun Tougher, "The Advocacy of an Empress: Julian and Eusebia" (The Classical Quarterly, New Series, Vol. 48, No. 2 (1998), pp. 595–599), argues that the kind Eusebia of Julian's panegyric is a literary creation and that she was doing the bidding of her husband in bringing Julian around to doing what Constantius had asked of him. See especially p. 597.

- David S. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay AD 180–395, p. 499.

- Most sources give the town as Sens, which is well into the interior of Gaul. See John F. Drinkwater, The Alamanni and Rome 213–496, OUP Oxford 2007, p. 220.

- Cambridge Ancient History, v. 13, p. 49.

- David S. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay AD 180–395, p. 501.

- David S. Potter, p. 501.

- Cambridge Ancient History, v.13, pp. 50–51.

- D. Woods, "On the 'Standard-Bearers' at Strasbourg: Libanius, or. 18.58–66", Mnemosyne, Fourth Series, Vol. 50, Fasc. 4 (August, 1997), p. 479.

- David S. Potter, pp. 501–502.

- Cambridge Ancient History, v.13, p. 51.

- Ammianus Marcellinus Res Gestae, 16.12.27ff, 38ff, 55

- Ammianus Marcellinus Res Gestae, 16.12.64–65

- John F. Drinkwater, The Alamanni and Rome 213–496, pp. 240–241.

- Athanassiadi, p. 69.

- grammation: cf. Zosimus, Historia Nova, 3.9, commented by Veyne, L'Empire Gréco-Romain, p. 45

- Julian, Letter to the Athenians, 282C.

- Ammianus Marcellinus Res Gestae, 20.4.1–2

- Ammianus Marcellinus. Res Gestae, 20.10.1–2

- Cambridge Ancient History, v. 13, pp. 56–57.

- David S. Potter, p. 506.

- Cambridge Ancient History v. 13, p. 58.

- Cambridge Ancient History v. 13, p. 59.

- In a private letter to his Uncle Julian, in W.C. Wright, v. 3, p. 27.

- J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Early Centuries, 89

- Cambridge Ancient History v. 13, p. 60.

- Athanassiadi, p. 89.

- Webb, Matilda. The Churches and Catacombs of Early Christian Rome: A Comprehensive Guide, pp. 249–252, 2001, Sussex Academic Press, ISBN 1-902210-58-1, 978-1-902210-58-2, google books

- Cambridge Ancient History v. 13, pp. 63–64.

- Cambridge Ancient History v. 13, p. 61.

- Cambridge Ancient History v. 13, p. 65.

- Bowersock, p. 95.

- Cambridge Ancient History v. 13, p. 69.

- Bowersock, p. 96.

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 22.12.8 – 22.13.3

- Socrates of Constantinople, Historia ecclesiastica, 3.18

- Libanius, Orations, 18.195 & 16.21

- Libanius, Orations, 1.126 & 15.20

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 22.14.1

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 22.14.3

- David S. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay, pp. 515–516

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 22.7.1, 25.4.17 (Commented by Veyne, L"Empire Gréco-Romain, p. 77)

- See Letter 622 by Libanius: "That Alexander was appointed to the government at first, I confess, gave me some concern, as the principal persons among us were dissatisfied. I thought it dishonourable, injurious, and unbecoming a prince; and that repeated fines would rather weaken than improve the city...." and the translator's note upon it: "This is the Alexander of whom Ammianus says (23.2), "When Julian was going to leave Antioch, he made one Alexander of Heliopolis, governor of Syria, a turbulent and severe man, saying that 'undeserving as he was, such a ruler suited the avaricious and contumellious Antiochians'." As the letter makes clear, Julian handed the city over to be looted by a man he himself regarded as unworthy, and the Christian inhabitants, who had dared to oppose his attempt to restore paganism, to be forced to attend and applaud pagan ceremonies at sword-point; and be 'urged' to cheer more loudly."

- Libanius, Oration 12, 76–77

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 22.12.1–2

- Zosimus, Historia Nova, book 3, chapter 12. Zosimus' text is ambiguous and refers to a smaller force of 18,000 under Procopius and a larger force of 65,000 under Julian himself; it's unclear if the second figure includes the first.

- Elton, Hugh, Warfare in Roman Europe AD 350–425, p. 210, using the higher estimate of 83,000.

- Bowersock, Julian the Apostate, p. 108.

- The Decline And Fall Of The Roman Empire, (The Modern Library, 1932), chapter XXIV., p. 807

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 23.2.1–2

- Ridley, Notes, p. 318.

- Bowersock, Julian the Apostate, p. 110.

- David S, Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay, p. 517.

- Libanius, Epistulae, 1402.2

- Dodgeon & Lieu, The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars, p. 203.

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 24.3.10–11.

- Dodgeon & Lieu, The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars, p. 204.

- Cambridge Ancient History, p. 75.

- Adrian Goldsworth, How Rome fell. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0-300-13719-4 , p. 232

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 24.7.1.

- David S. Potter, Rome in the ancient world, pp. 287–290.

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 24.8.1–5.

- Dodgeon & Lieu, The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars, p. 205.

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 25.3.3

- Lascaratos, John and Dionysios Voros. 2000 Fatal Wounding of the Byzantine Emperor Julian the Apostate (361–363 A.D.): Approach to the Contribution of Ancient Surgery. World Journal of Surgery 24: 615–619. See p. 618.

- Grant, Michael. The Roman Emperors. (New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 1997), p. 254.

- Libanius, Orations, 18.274

- John Malalas, Chronographia, pp. 333–334. Patrologia Graeca XCII, col. 496.

- evidence preserved by Philostorgius, see David S. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay AD 180–395, p. 518.

- Sozomenus, Historia ecclesiastica, 6.2

- Theodoret, Historia ecclesiastica, 3.25

- Kathleen McVey (Editor), The Fathers of the Church: Selected Prose Works (1994) p. 31

- Libanius, Oration 18, 306; Ammianus Marcellinus 23, 2.5 and 25, 5.1. References from G. Downey,The tombs of the Byzantine emperors at the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, Journal of Hellenic Studies 79 (1959) p. 46

- Downey gives the text: '...later the body was transferred to the imperial city' (xiii 13, 25)

- Glanville Downey, The tombs of the Byzantine emperors at the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, Journal of Hellenic Studies 79 (1959) 27–51. On p. 34 he states that the Book of Ceremonies of Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus gives a list of tombs, ending with: "43. In this stoa, which is to the north, lies a cylindrically-shaped sarcophagus, in which lies the cursed and wretched body of the apostate Julian, porphyry or Roman in colour. 44 Another sarcophagus, porphyry, or Roman, in which lies the body of Jovian, who ruled after Julian."

- Vasiliev, A. A. (1948). "Imperial Porphyry Sarcophagi in Constantinople" (PDF). Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 4: 1+3–26. doi:10.2307/1291047. JSTOR 1291047.

- The emperor's study of Iamblichus and of theurgy are a source of criticism from his primary chronicler, Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 22.13.6–8 and 25.2.5

- Tougher, Shaun (2007). Julian the Apostate. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 27ff, 58f. ISBN 9780748618873.

- Julian, "Letter to a Priest", 292. Transl. W.C. Wright, v. 2, p. 307.

- As above. Wright, v. 2, p. 305.

- Julian, "Against the Galilaeans", 143. Transl. W.C. Wright, v. 3, p. 357.

- Thomas F. Gossett, Race: The History of an Idea in America, 1963 (Southern Methodist University Press) /1997 (Oxford University Press, US), p. 8.

- Socrates Scholasticus, Church History, iii, 21.

- Gibbon, Edward. The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Chapter 22.

- Brown, Peter, The World of Late Antiquity, W. W. Norton, New York, 1971, p. 93.

- Julian, Epistulae, 52.436A ff.

- Richard T. Wallis, Jay Bregman (1992). Neoplatonism and Gnosticism. p. 22. ISBN 9780791413371.

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 22.5.4.

- See Roberts and DiMaio.

- Adrian Murdoch, The Last Pagan (UK: Sutton Publishing Limited, 2003), 3.

- Adrian Murdoch, The Last Pagan (UK: Sutton Publishing Limited, 2003), 4.

- Scott Bradbury, "Julian's Pagan Revival and the Decline of Blood Sacrifice," Phoenix 49 (1995), 331.

- Scott Bradbury, "Julian's Pagan Revival and the Decline of Blood Sacrifice," Phoenix 49 (1995).

- Jonathan Kirsch, God against the Gods (New York: Penguin Group, 2004), 9.

- Scott Bradbury, "Julian's Pagan Revival and the Decline of Blood Sacrifice," Phoenix 49 (1995): 333.

- Scott Bradbury, "Julian's Pagan Revival and the Decline of Blood Sacrifice," Phoenix 49 (1995): 352.

- Scott Bradbury, "Julian's Pagan Revival and the Decline of Blood Sacrifice," Phoenix 49 (1995): 354.

- Harold Mattingly, “The Later Paganism,” The Harvard Theological Review 35 (1942): 178.

- Harold Mattingly, “The Later Paganism,” The Harvard Theological Review 35 (1942): 171.

- James O’Donnell, “The Demise of Paganism,” Traditio 35 (1979): 53, accessed September 23, 2014, JSTOR 27831060

- St. John Chrysostom, The Cult of the Saints (select homilies and letters), Wendy Mayer & Bronwen Neil, eds., St. Vladimir's Seminary Press (2006).

- Quoted in : Schmidt, Charles (1889). The Social Results of Early Christianity (2 ed.). Wm. Isbister. p. 328. Retrieved 2013-02-09.

- Jacob Neusner (15 September 2008). Judaism and Christianity in the Age of Constantine: History, Messiah, Israel, and the Initial Confrontation. University of Chicago Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-226-57647-3.

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 23.1.2–3.

- Kavon, Eli (4 December 2017). "Julian and the dream of a Third Temple". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica: Or, Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature, Volume 8; Volume 12. Little, Brown & Company. 1856. p. 744.

In A.D. 363, the Emperor Julian undertook to rebuild the temple, but after considerable preparations and much expense he was compelled to desist by flames which burst forth from the foundations. Repeated attempts have been made to account for these igneous explosions by natural causes; for instance, by the ignition of gases which had long been pent up in the subterraneous vaults.

- Edward Gibbon, The Decline And Fall Of The Roman Empire, (The Modern Library), chapter XXIII., pp. 780–82, note 84

- See "Julian and the Jews 361–363 CE" (Fordham University, The Jesuit University of New York) and "Julian the Apostate and the Holy Temple" Archived 2005-10-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Falk, Avner, A Psychoanalytic History of the Jews (1996), Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, London, ISBN 0-8386-3660-8.

- Athanassiadi, p. 61.

- Athanassiadi, pp. 62–63.

- The manuscript tradition uses the name "Sallustius", but see Bowersock, p. 45 (footnote #12), and Athanassiadi, p. 20.

- Athanassiadi, p. 85.

- Athanassiadi, p. 90.

- Athanassiadi, p. 131.

- Athanassiadi, p. 141, "at the same time" as To The Cynic Heracleios.

- Athanassiadi, p. 137.

- Athanassiadi, p. 197, written for the Saturnalia festival, which began December 21.

- "Julian: Caesars – translation". www.attalus.org.

- Athanassiadi, p. 148, doesn't supply a clear date. Bowersock, p. 103, dates it to the celebration of Sol Invictus, December 25, shortly after the Caesars was written.

- Athanassiadi, p. 201, dates it "towards the end of his stay in Antioch".

- Athanassiadi, p. 161. – Wikisource:Against the Galileans

- Wright, Wilmer (1923). Letters. Epigrams. Against the Galilaeans. Fragments. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. xxvii–xxviii. ISBN 9781258198077.

- Trapp, Michael (2012). Baker-Brian & Tougher, Nicholas & Shaun (ed.). The Emperor's Shadow: Julian in his Correspondence. Emperor and Author: The Writings of Julian the Apostate. Swansea: Classical Press of Wales. p. 105. ISBN 978-1905125500.

- Wright, Wilmer (1923). Julian. Letters. Epigrams. Against the Galilaeans. Fragments. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 208-209. ISBN 978-0674991736.

- Wright, Wilmer (1913). Julian, Volume II. Orations 6–8. Letters to Themistius. To The Senate and People of Athens. To a Priest. The Caesars. Misopogon. Loeb Classical Library (Book 29). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 295. ISBN 978-0674990326.

- Pearse, Roger (2003). "Oration 4: First Invective Against Julian".

- Pearse, Roger (2003). "Oration 5: Second Invective Against Julian".

- Wright, Wilmer (1923). Julian. Letters. Epigrams. Against the Galilaeans. Fragments. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 453–454. ISBN 9781258198077.

- Wright, Wilmer (1913). Julian, Orations 6–8. Letters to Themistius, To the Senate and People of Athens, To a Priest. The Caesars. Misopogon. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 338–339. ISBN 978-0674990326.

- Wright, Wilmer (1923). Julian. Letters. Epigrams. Against the Galilaeans. Fragments. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 9781258198077.

- Christopher Clark, "Iron Kingdom", p. 446

- Coustillas, Pierre ed. London and the Life of Literature in Late Victorian England: the Diary of George Gissing, Novelist. Brighton: Harvester Press, 1978, p. 237.

Ancient sources

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, Libri XV-XXV (books 15–25). See J.C. Rolfe, Ammianus Marcellinus, Harvard University Press, Cambridge Mass., 1935/1985. 3 Volumes.

- Ammianus Marcellinus, The Roman History of Ammianus Marcellinus During the Reigns of the Emperors Constantius, Julian, Jovianus, Valentinian, and Valens. Translated by C. D. Yonge. Full text at Internet Archive at The Roman History of Ammianus Marcellinus During the Reigns of the Emperors Constantius, Julian, Jovianus, Valentinian, and Valens. Gutenberg etext# 28587.

- Julian the emperor: containing Gregory Nazianzen's two Invectives and Libanius' Monody : with Julian's extant theosophical works., Translated by C.W. King. George Bell and Sons, London, 1888. At the Internet Archive

- Claudius Mamertinus, "Gratiarum actio Mamertini de consulato suo Iuliano Imperatori", Panegyrici Latini, panegyric delivered in Constantinople in 362, also as a speech of thanks at his assumption of the office of consul of that year

- Gregory Nazianzen, Orations, "First Invective Against Julian", "Second Invective Against Julian". Both transl. C.W. King, 1888.

- Libanius, Monody — Funeral Oration for Julian the Apostate. Transl. C.W. King, 1888.

Modern sources

- Athanassiadi, Polymnia (1992) [1981]. Julian: An Intellectual Biography. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-07763-X.

- Baker-Brian, Nicholas; Tougher, Shaun. (2012). Emperor and Author: The Writings of Julian the Apostate. The Classical Press of Wales. Swansea. ISBN: 978-1-905125-50-0. http://www.classicalpressofwales.co.uk/emperor_author.htm

- Bowersock, G.W. (1978). Julian the Apostate. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-1262-X.

- Browning, Robert (1975). The Emperor Julian. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-77029-2.

- Dodgeon, Michael H. & Samuel N.C. Lieu, The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars AD 226–363, Routledge, London, 1991. ISBN 0-203-42534-0

- Drinkwater, John F., The Alamanni and Rome 213–496 (Caracalla to Clovis), OUP Oxford 2007. ISBN 0-19-929568-9

- Lascaratos, John and Dionysios Voros. 2000 Fatal Wounding of the Byzantine Emperor Julian the Apostate (361–363 A.D.): Approach to the Contribution of Ancient Surgery. World Journal of Surgery 24: 615–619

- Murdoch, Adrian. The Last Pagan: Julian the Apostate and the Death of the Ancient World, Stroud, 2005, ISBN 0-7509-4048-4

- Phang, Sara E.; Spence, Iain; Kelly, Douglas; Londey, Peter, eds. (2016). Conflict in Ancient Greece and Rome: The Definitive Political, Social, and Military Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO.

- Potter, David S. The Roman Empire at Bay AD 180–395, Routledge, New York, 2004. ISBN 0-415-10058-5

- Ridley, R.T., "Notes on Julian's Persian Expedition (363)", Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, Vol. 22, No. 2, 1973, pp. 317–330

- Roberts, Walter E. & DiMaio, Michael (2002), "Julian the Apostate (360–363 A.D.)", De Imperatoribus Romanis

- Smith, Rowland. Julian's gods: religion and philosophy in the thought and action of Julian the Apostate, London, 1995. ISBN 0-415-03487-6

- Veyne, Paul. L'Empire Gréco-Romain. Seuil, Paris, 2005. ISBN 2-02-057798-4

- Wiemer, Hans-Ulrich & Stefan Rebenich, eds. (2020). A Companion to Julian the Apostate. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-41456-3.

Further reading

- García Ruiz, María Pilar, "Julian's Self-Representation in Coins and Texts." In Imagining Emperors in the Later Roman Empire, Ed. D.W.P. Burgersdijk and A.J. Ross. Leiden. Brill. 2018. 204-233. ISBN. 978-90-04-37089-0.

- Gardner, Alice, Julian Philosopher and Emperor and the Last Struggle of Paganism Against Christianity, G.P. Putnam's Son, London, 1895. ISBN 0-404-58262-1 / ISBN 978-0-404-58262-3. Downloadable at Julian, philosopher and emperor.

- Hunt, David. "Julian". In The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 13 (Averil Cameron & Peter Garnsey editors). CUP, Cambridge, 1998. ISBN 0-521-30200-5

- Kettenhofen, Erich (2009). "JULIAN". JULIAN – Encyclopaedia Iranica. Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XV, Facs. 3. pp. 242–247.

- Lenski, Noel Emmanuel Failure of Empire: Valens and the Roman State in the Fourth Century AD University of California Press: London, 2003

- Lieu, Samuel N.C. & Dominic Montserrat: editors, From Constantine to Julian: A Source History Routledge: New York, 1996. ISBN 0-203-42205-8