Estonian Centre Party

The Estonian Centre Party (Estonian: Eesti Keskerakond) is a social-liberal[2][3][4] and populist[5][6][7] political party in Estonia. It is one of the two largest political parties in Estonia and currently has 26 seats in the Estonian Parliament. The party is a member of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE) and Renew Europe.

Estonian Centre Party Eesti Keskerakond | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leader | Jüri Ratas |

| Founded | 12 October 1991 |

| Preceded by | Popular Front of Estonia |

| Headquarters | Narva mnt. 31-M1 Tallinn 10120 |

| Membership (2021) | |

| Ideology |

Factions: Russian minority politics[8][9] |

| Political position | Centre[2][10] to centre-left[11][12] |

| European affiliation | Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe |

| European Parliament group | Renew Europe |

| Colours | Green |

| Riigikogu | 25 / 101 |

| European Parliament (Estonian seats) | 1 / 7 |

| Website | |

| http://www.keskerakond.ee/ | |

The party was founded on 12 October 1991 from the basis of the Popular Front of Estonia after several parties split from it. At that time, the party was called the People's Centre Party (Rahvakeskerakond) in order to differentiate from the smaller centre-right Rural Centre Party (Maa-Keskerakond). The Centre Party chairman since 5 November 2016 has been Jüri Ratas.[13] The party is described as centrist[2][10] and in favour of the social market economy.[14]

As of 26 January 2021, the party has been a member of the Kallas government, a grand coalition with the Estonian Reform Party.

History

In the parliamentary elections of March 1995, the Centre Party was placed third with 14.2% of votes and 16 seats. It entered the coalition, Edgar Savisaar taking the position of the Minister of Internal Affairs, and 4 other ministerial positions (Social Affairs, Economy, Education and Transportation& Communications). After the "tape scandal" (secret taping of talks with other politicians) in which Savisaar was involved, the party was forced to go to opposition. A new party was formed by those who were disappointed by their leader's behaviour. Savisaar became the Chairman of the City Council of the capital city Tallinn.

In 1996, CPE candidate Siiri Oviir ran for the presidency of Estonia.

In the parliamentary elections of March 1999, the Centre Party, whose main slogan was progressive income tax, gained 23.4% of votes (the first result) and 28 seats in the Riigikogu. CPE members are active in its 26 branches – eight of them are active in Tallinn, 18 in towns and counties.

The Centre Party became a member of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Party (then known as the European Liberal Democrat and Reform Party) at the organisation's July 2003 London Congress. The party also applied for the membership of the Liberal International (LI) in 2001, but the LI decided to reject the party's application in August 2001, as Savisaar's conduct was adjudged to 'not always conform to liberal principles'.[15]

In 2001, Kreitzberg unsuccessfully ran for the presidency of Estonia.

Savisaar was the Mayor of Tallinn, the capital of Estonia, from 2001 to fall 2004, when he was forced to step down after a vote of no confidence. He was replaced by Tõnis Palts of Res Publica.

In January 2002, the Centre Party and the Estonian Reform Party formed a new governmental coalition where Centre Party got 8 ministerial seats (Minister of Defense, Education, Social Affairs, Finances, Economy & Communications, Interior, Agriculture and Minister of integration and national minorities). The coalition stayed until the new elections in 2003, in which the party won 28 seats. Though the Centre Party won the greatest percent of votes, it was in opposition until March, 2005 when Juhan Parts' government collapsed.

In 2003, the majority of the party's assembly did not support Estonia's joining the European Union (EU). Savisaar did not express clearly his position.

A number of Centre Party members exited the party in autumn 2004, mostly due to objections with Savisaar's autocratic tendencies and the party's EU-sceptic stance, forming the Social Liberal group. Some of them joined the Social Democratic Party, others the Reform Party and others the People's Party. One of these MPs later rejoined the Centre Party. Since Estonia's accession to the EU, the party has largely revised its formerly EU-sceptic positions.[12]

In 2004 the Centre Party gained one member in the European Parliament – Siiri Oviir. The Centre Party gathered 17.5% share of votes on the elections to the European Parliament. Oviir joined the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE) Group.

The Centre Party participated in government with the Estonian Reform Party and the People's Union of Estonia from 12 April 2005 until a new government took office after the March 2007 elections. The Centre Party had 5 minister portfolios (Edgar Savisaar as Minister of Economy, also Minister of Social Affairs, Education, Culture and Interior).

Local elections on 16 October 2005 were very successful to the Centre Party. It managed to win 32 seats out of 63 in Tallinn City Council, having now an absolute majority in that municipality. One of the factors behind this success in Tallinn was probably the immense popularity of Centre Party among Russian speaking voters. The controversial contract of co-operation between the Estonian Centre Party and the Russia's dominant political party of power United Russia has probably contributed to the success in ethnic Russian electorate as well.

Centre Party formed one-party government in Tallinn led by Jüri Ratas, a 27-year-old politician elected the Mayor of Tallinn in November 2005. He was replaced by Savisaar in April 2007.[16] The Centre Party is also a member of coalitions in 15 other major towns of Estonia like Pärnu, Narva, Haapsalu and Tartu.

In the 2007 Estonian parliamentary election, the party received 143,528 votes (26.1% of the total), an improvement of +0.7%. They took 29 seats, a gain of one seat compared to the 2003 elections, though due to the 2004 defections which had decreased their strength, they actually gained 10 seats. They are now the second largest party in Parliament and the largest opposition party. In 2008, the party criticised Andrus Ansip's policies, that in Centre Party's opinion have contributed to Estonia's economic problems of recent times. On June 16, 2007, Edgar Savisaar and Jaan Õmblus published a proposal of how to improve what they regard as Estonia's economic crisis.[17]

In the European Parliament elections of 2009, the Centre Party gained the most votes and 2 out of 6 Estonian seats, which were filled by Siiri Oviir and Vilja Savisaar.

In local elections of 2009, the party strengthened its absolute majority in the Tallinn city council. Despite their absolute majority, they formed a coalition with the Social Democratic Party. Recent polls suggest the party is especially popular amongst Estonia's Russophone minority.[18]

On 9 April 2012 eight prominent Centre Party members decided to leave the party citing frustration of their attempts to bring openness and transparency into party leadership. Previously MP Kalle Laanet was expelled on 21 March for his criticism of the party leadership. The leaving politicians included MEPs Siiri Oviir and Vilja Savisaar-Toomast, MPs Inara Luigas, Lembit Kaljuvee, Deniss Boroditš and Rainer Vakra, and also Ain Seppik, Toomas Varek.[19]

In the local elections of 20 October 2013, the Center Party and its leader Edgar Savisaar were successful, obtaining the absolute majority in the city of Tallinn with 53% of votes, winning 46 seats out of 79 (2 more than the 2009 results), considerably more than the second party, the Pro Patria and Res Publica Union, which received 19% of votes and 16 seats.[20]

The Estonian Centre Party obtained a good result in the 2015 election, obtaining 24.8% of votes and electing 27 MPs. The party remained in opposition to the new government of Taavi Rõivas, which was supported by the Estonian Reform Party, the Social Democratic Party and the Pro Patria and Res Publica Union.

In Autumn 2016 Savisaar stepped down as party leader and Jüri Ratas was elected in his place.

In November 2016 the Social Democratic Party and the Pro Patria Union withdrew from the government coalition and entered a no-confidence motion against the government, together with the Estonian Centre Party. On 9 November 2016 the Riigikogu approved the motion with a 63–28 vote and Rõivas was forced to resign; in a following coalition talk, the Centre Party, SDE and IRL formed a new coalition led by Center Party's chairman Jüri Ratas. The new government was sworn in on 23 November.[21][22]

Parliamentary elections of 2019

In the 2019 parliamentary election, the Centre Party lost support while the opposition Estonian Reform Party gained support and won a plurality in election. After the election, the head of the Centre Party, Jüri Ratas turned down an offer by the Reform Party for coalition talks and entered into talks with Isamaa and Conservative People's Party of Estonia (EKRE), the latter widely considered a far-right party. Ratas had previously ruled out forming a coalition with EKRE during the election campaign because of its hostile views.[23] The inclusion of EKRE in coalition talks after the elections was met with local and international criticism. In a poll conducted after the start of the coalition talks, the party of Jüri Ratas further lost support.[24][25][26]

The critics of the decision have claimed that Ratas is willing to sacrifice his party's values, the confidence of his voters and the stability and reputation of the country to keep his position as prime minister. Ratas has countered that his first duty is to look for ways to get his party included in the government to be able to work in the benefit of his voters and that the coalition would continue to firmly support the EU, NATO and would be sending out messages of tolerance.[27][28][29]

Some key members and popular candidates of the party have been critical of the decision, with Raimond Kaljulaid leaving the board of the party in protest. Yana Toom, a member of the Centre Party and its representative in the European Parliament expressed criticism of the decision. Mihhail Kõlvart, popular among the Russian-speaking voters, has said the Centre Party cannot govern with EKRE's approach.[30][31][32] On 5 April 2019, Raimond Kaljulaid announced his decision to quit the party, deciding to sit as an independent member of the Parliament.[33]

In January 2021, after the resignation of Jüri Ratas as Prime Minister, Kaja Kallas formed a Estonian Reform Party-led grand coalition government with the Estonian Centre Party.[34]

Ideology

The party claims that its goal is the formation of a strong middle class in Estonia. The Centre Party declares itself as a "middle class liberal party"; however, against the backdrop of Estonia's economically liberal policies, the Centre Party has a reputation of having more left-leaning policies. This is despite the fact that the party holds positions considered contrary to social liberalism on a number of issues. For example, the party suggests that Estonia should deliberate re-establishing criminal punishments for the possession of even small amounts of illegal substances.[35] Nor could Centre Party's parliamentary faction agree on its stance in regards to same-sex marriage,[36] which is traditionally supported by social liberals. In an Estonian Public Broadcasting program 'Foorum', Estonian Reform Party parliamentarian Remo Holsmer listed the ideologies of other three political parties represented in the Parliament, but could not name the ideological position of the Centre Party. Centre Party parliamentarian Kadri Simson then tried to clarify that the ideology of the Centre Party is "Centre Party," meaning a unique ideology independent of other established ones.[37]

The party is often described as populist[5][6][7] and critics have accused its long-time leader Edgar Savisaar of authoritarianism until a new leader was elected in 2016.[38]

Historically, the party has been the most popular party among Russian-speaking citizens. In 2012, it was supported by up to 75% of ethnic non-Estonians.[39]

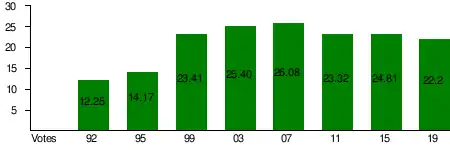

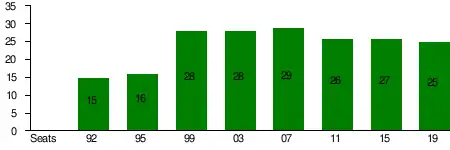

Electoral performance

| Election | Votes | % | Seats | +/– | Position | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 56,124 | 12.2 | 15 / 101 |

Opposition | ||

| 1995 | 76,634 | 14.2 | 16 / 101 |

Coalition | ||

| 1999 | 113,378 | 23.4 | 28 / 101 |

Coalition (2002–2003) | ||

| 2003 | 125,709 | 25.4 | 28 / 101 |

Opposition | ||

| 2007 | 143,518 | 26.1 | 29 / 101 |

Opposition | ||

| 2011 | 134,124 | 23.3 | 26 / 101 |

Opposition | ||

| 2015 | 142,442 | 24.8 | 27 / 101 |

Coalition (2016–2019) | ||

| 2019 | 118,561 | 23.0 | 26 / 101 |

Coalition |

References

- "The list of the members: Eesti Keskerakond". e-business register. Retrieved 15 Jan 2021.

- Nordsieck, Wolfram (2019). "Estonia". Parties and Elections in Europe.

- World and Its Peoples. Marshall Cavendish. 2010. p. 1060. ISBN 978-0-7614-7896-6.

- Elisabeth Bakke (2010). "Central and East European party systems since 1989". In Sabrina P. Ramet (ed.). Central and East European party systems since 1989. Central and Southeast European Politics since 1989. Cambridge University Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-139-48750-4.

- Bugajski, Janusz; Teleki, Ilona (2007), Atlantic Bridges: America's New European Allies, Rowman & Littlefield, p. 192

- Huang, Mel (2005), "Estonia", Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands and Culture, ABC-CLIO, p. 89

- "Estonian Centre Party", A Political and Economic Dictionary of Eastern Europe (First ed.), Cambridge International Reference on Current Affairs, p. 201, 2002

- Aidarov, Aleksandr; Drechsler, Wolfgang (2011). "The Law & Economics of the Estonian Law on Cultural Autonomy for National Minorities and of Russian National Cultural Autonomy in Estonia" (PDF). Halduskultuur. 12 (1): 43–61. ISSN 1736-6089.

- Sebald, Christoph; Matthews-Ferrero, Daniel; Papalamprou, Ery; Steenland, Robert (14 May 2019). "EU country briefing: Estonia". EURACTIV. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- Andrejs Plakans (2011), A Concise History of the Baltic States, Cambridge University Press, p. 424

- Micael Castanheira; Gaëtan Nicodème; Paola Profeta (2010), "On the Political Economics of Taxation", Public choice e political economy, FrancoAngeli, p. 94

- Allan Sikk (2011), "The Case of Estonia", Party Politics in Central and Eastern Europe: Does EU membership matter?, Routledge, p. 60

- , Postimees, 5 November 2016

- Olesk, Peeter (19 July 2017). "Mis on Keskerakonna ideoloogia?" [What is Centre Party's ideology?] (in Estonian). Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- Day, Alan John (2002). Political parties of the world. London: John Harper. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-9536278-7-5.

- "Article". baltictimes.com.

- "Keskerakond". Archived from the original on 2008-06-19.

- "Keskerakond on jätkuvalt muulaste seas populaarseim erakond - Eesti uudised". Postimees. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- Sivonen, Erkki (9 April 2012). "Eight Top-Ranking Members to Leave Centre Party". Eesti Rahvusringhääling. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- "Valimistulemused". Delfi.ee. 21 October 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ERR (2016-11-09). "Prime Minister loses no confidence vote, forced to resign". ERR. Retrieved 2018-10-15.

- ERR (2016-11-23). "President appoints Jüri Ratas' government". ERR. Retrieved 2018-10-15.

- ERR (22 November 2018). "Ratas peab koalitsiooni EKRE-ga võimatuks". ERR.

- "Kõlvart: erakonna püsimine on tähtsam kui olemine opositsioonis". Poliitika. 13 March 2019.

- "Uuring: valijad eelistavad kõike muud kui Keskerakonna-EKRE-Isamaa liitu". Poliitika. 14 March 2019.

- "Estonian PM invites far-right to join cabinet". 12 March 2019 – via www.reuters.com.

- "Jüri Ratase ränk solvumine: Keskerakonna esimees on võimu nimel kõigeks valmis". Eesti Ekspress. 12 March 2019.

- "Keskerakond ei nõustu Reformierakonna ühiskondlikku ebavõrdsust suurendava ettepanekuga - Keskerakond". keskerakond.ee.

- "Jüri Ratas: "See küsimus on juba eos vale"". Poliitika. 14 March 2019.

- ERR, Mait Ots (12 March 2019). "Kaljulaid ERR-ile: enne lõhenegu Keskerakond, kui EKRE võimule aidatakse". ERR.

- ERR (11 March 2019). "Toom: ma ei näe EKRE-s väärilist partnerit". ERR.

- "Kõlvart on EKRE's views: We cannot govern with their approach". ERR. 12 March 2019.

- "Raimond Kaljulaid quits Centre Party". ERR. ERR. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- "Kaja Kallas to become Estonia's first female prime minister". euronews. 2021-01-24. Retrieved 2021-01-25.

- "Yana Toom: narkomaane peab karmimalt karistama". Arvamus. Retrieved 11 September 2012. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Merje Pors. "Keskerakond ei jõua partnerlusseaduse osas kokkuleppele". Postimees. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- Simson, Kadri (2012-05-23). Foorum (Motion picture) (in Estonian). Tallinn, Estonia: Estonian Public Broadcasting. Event occurs at 21:47. Archived from the original on 2012-07-11.

- Jeffries, Ian (2004), The Countries of the Former Soviet Union at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century: The Baltic and European states in transition, Routledge, p. 141

- Keskerakond on mitte-eestlaste seas jätkuvalt populaarseim partei, Postimees, 23 September 2012