European emigration

European emigration can be defined as subsequent emigration waves from the European continent to other continents. The origins of the various European diasporas[35] can be traced to the people who left the European nation states or stateless ethnic communities on the European continent.[36]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 550,000,000+ 7% of the global population (7,800,000,000)[1] of full European ancestry outside Europe[2] 950,000,000+ including Latin American Mestizos and South African Coloureds of partial European ancestry | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 243,832,540[3] | |

| 110,000,000[4][5] | |

| 59,000,000[6][7][8][9] | |

| 37,000,000[6][10][11][12] | |

| 33,000,000[13] | |

| 27,386,890[14] | |

| 23,000,000[15] | |

| 19,500,350[16][17] | |

| 13,094,085[18][19][20] | |

| 11,577,670[6] | |

| 7,050,000[21] | |

| 4,586,838[22] | |

| 4,172,601[23] | |

| 3,900,000[6] | |

| 3,372,708[24] | |

| 3,101,095[25] | |

| 3,064,862[26] | |

| 2,000,000+[20] | |

| 1,400,000+[27] | |

| 1,320,000+[28] | |

| 1,300,000+[29] | |

| 1,200,000+[6] | |

| 1,105,000[30] | |

| 548,000+[20] | |

| 200,000+[31](680,000 mixed race)[32] | |

| 150,000[33] | |

| Languages | |

| Languages of Europe (mostly English, Spanish, Portuguese, minority of French, Dutch, Polish, German and Italian) | |

| Religion | |

(mostly Catholic and Protestant, some Orthodox) Irreligion · Other Religions | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Europeans | |

From 1815 to 1932, 60 million people left Europe (with many returning home), primarily to "areas of European settlement" in the Americas (especially to the United States, Canada, Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay[36]), South Africa, Australia,[37] New Zealand and Siberia.[38] These populations also multiplied rapidly in their new habitat; much more so than the populations of Africa and Asia. As a result, on the eve of World War I, 38% of the world's total population was of European ancestry.[38]

More contemporary, European emigration can also refer to emigration from one European country to another, especially in the context of the internal mobility in the European Union (intra-EU mobility) or mobility within the Eurasian Union.

From 1500 to the mid-20th century, 60-65 million people left Europe, of which less than 5% went to tropical areas (the Caribbean, Asia, and Africa).[39]

History

8th - early 5th century BC: Greeks

In Archaic Greece, trading and colonizing activities of the Greek tribes from the Balkans and Asia Minor propagated Greek culture, religion and language around the Mediterranean and Black Sea basins. Greek city-states were established in Southern Europe, northern Libya and the Black Sea coast, and the Greeks founded over 400 colonies in these areas.[40] Alexander the Great's conquest of the Achaemenid Empire marked the beginning of the Hellenistic period, which was characterized by a new wave of Greek colonization in Asia and Africa; the Greek ruling classes established their presence in Egypt, southwest Asia, and Northwest India.[41] Many Greeks migrated to the new Hellenistic cities founded in Alexander's wake, as geographically-dispersed as Uzbekistan[42] and Kuwait.[43]

Colonial settlers

The European continent has been a central part of a complex migration system, which included swaths of North Africa, the Middle East and Asia Minor well before the Modern Era. Yet, only the population growth of the late Middle Ages allowed for larger population movements, inside and outside of the continent.[44] The discovery of the Americas in 1492 stimulated a steady stream of voluntary migration from Europe. About 200,000 Spaniards settled in their American colonies prior to 1600, a small settlement compared to the 3 to 4 million Amerindians who lived in Spanish territory in the Americas.

Roughly one and a half million Europeans settled in the New World between 1500 and 1800 (see table). The Table excludes European immigrants to the Spanish Empire from 1650-1800 and to Brazil from 1700 to 1800. While the absolute number of European emigrants during the early modern period was very small compared to later waves of migration in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the relative size of these early modern migrations was nevertheless substantial.

During the 1500s, Spain and Portugal sent a steady flow of government and church officials, members of the lesser nobility, people from the working classes and their families averaging roughly three-thousand people per year from a population of around eight million. A total of around 437,000 left Spain in the 150-year period from 1500 to 1650 to Central, South America and the Caribbean Islands. It has been estimated that over 1.86 million Spaniards emigrated to Latin America in the period between 1492 and 1824, one million in the 18th century, with millions more continuing to immigrate following independence.[45]

Between 1500 and 1700 only 100,000 Portuguese crossed the Atlantic to settle in Brazil. However, with the discovery of numerous highly productive gold mines in the Minas Gerais region, the Portuguese emigration to Brazil increased by fivefold. From 1500, when the Portuguese reached Brazil, until its independence in 1822, from 500,000 to 700,000 Portuguese settled in Brazil, 600,000 of whom arrived in the 18th century alone.[46] From 1700 til 1760 over half a million Portuguese immigrants entered Brazil. In the 18th century, thanks to the gold rush, the capital of the province of Minas Gerais, the town of Villa Rica (today, Ouro Preto) became for a time one of the most populous cities in the New World. This massive influx of Portuguese immigration and influence created a city which remains to this day, one of the best examples of 18th century European architecture in the Americas.[36] However, the development of the mining economy in the 18th century raised wages and employment opportunities in the Portuguese colony and emigration increased: in the 18th century alone, about 600,000 Portuguese settled in Brazil, a mass emigration given that Portugal had a population of only 2 million people.[47]

Between one-half and two-thirds of European immigrants to the Thirteen Colonies between the 1630s and the American Revolution came under indentures.[48] The practice was sufficiently common that the Habeas Corpus Act 1679, in part, prevented imprisonments overseas; it also made provisions for those with existing transportation contracts and those "praying to be transported" in lieu of remaining in prison upon conviction.[49] In any case, while half the European immigrants to the Thirteen Colonies had been indentured servants, at any one time they were outnumbered by workers who had never been indentured, or whose indenture had expired. Free wage labour was more common for Europeans in the colonies.[50] Indentured persons were numerically important mostly in the region from Virginia north to New Jersey. Other colonies saw far fewer of them. The total number of European immigrants to all 13 colonies before 1775 was about 500,000-550,000; of these 55,000 were involuntary prisoners. Of the 450,000 or so European arrivals who came voluntarily, Tomlins estimates that 48% were indentured.[51] About 75% were under the age of 25. The age of legal adulthood for men was 24 years; those over 24 generally came on contracts lasting about 3 years.[51] Regarding the children who came, Gary Nash reports that, "many of the servants were actually nephews, nieces, cousins and children of friends of emigrating Englishmen, who paid their passage in return for their labour once in America."[52] Figures for immigration the Spanish Empire 1650-1800 and Brazil 1700-1800 are not given in the Table.

| Number of European Emigrants 1500-1783 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country of Origin | Number | Period | |

| Spain | 437,000 | 1500-1650 | |

| Portugal | 100,000 | 1500-1700 | |

| Great Britain | 400,000 | 1607-1700 | |

| Great Britain (Totals) | 322,000 | 1700-1780 | |

| Scotland, Ireland | 190,000-250,000 | ||

| France | 51,000 | 1608-1760 | |

| Germany (Southwestern, Totals) | 100,000 | 1683-1783 | |

| Switzerland, Alsace-Lorraine | |||

| Totals | 1,410,000 | 1500-1783 | |

Source:[36] | |||

In North America, immigration was dominated by British, Irish, French and other Northern Europeans.[53] Emigration to New France laid the origins of modern Canada, with important early immigration of colonists from Northern France.[47]

Post-independence emigration

Mass European emigration to the Americas, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand took place in the 19th and 20th centuries. This was the effect of a dramatic demographic transition in 19th-century-Europe, subsequent wars and political changes on the continent. From the end of the Napoleonic Wars until 1920, some 60 million Europeans emigrated. Of these, 71% went to North America, 21% to Latin America (mainly Argentina and Brazil) and 7% to Australia. About 11 million of these people went to Latin America, of whom 38% were Italians, 28% were Spaniards and 11% were Portuguese.[54]

Between 1821 and 1890, 9.55 million Europeans settled in the United States, mainly Germans, Irish, English, Scandinavians, Italians, Scots, and Poles. 18 million more arrived from 1890 to 1914, including 2.5 million from Canada. Despite the large number of immigrants arriving, people born outside of the United States formed a relatively small number of the U.S. population: in 1910, foreigners accounted for 14.7 percent of the country's population or 13.5 million people. The huge number of immigrants to Argentina, which had a much smaller population, had a much greater impact on the country's ethnic composition. By 1914, 30% of Argentina's population was foreign-born, with 12% of its population born in Italy, the largest immigrant group. Next was Canada: by 1881, 14% of Canada's population was foreign-born, and the proportion increased to 22% in 1921.

In Brazil, the proportion of immigrants in the national population was much smaller, and immigrants tended to be concentrated in the central and Southern parts of the country. The proportion of foreigners in Brazil peaked in 1920, at just 7 percent or 2 million people, mostly Italians, Portuguese, Germans and Spaniards; however, the influx of 4 million European immigrants between 1880 and 1920 significantly altered the racial composition of the country.[53] From 1901 to 1920, immigration was responsible for only 7 percent of Brazilian population growth, but in the years of high immigration, from 1891 to 1900, the share was as high as 30 percent (higher than Argentina's 26 percent in the 1880s).[55]

The countries in the Americas that received a major wave of European immigrants from 1820s to the early 1930s were: the United States (32.5 million), Argentina (6.5 million), Canada (5 million), Brazil (4.3 million), Cuba (1.3 million), Chile (728,000),[56] Uruguay (713,000).[57] Other countries that received a more modest immigration flow (accounting for less than 10 percent of total European emigration to Latin America) were: Mexico (270,000), Colombia (126,000), Puerto Rico (62,000), Peru (30,000), and Paraguay (21,000).[57][55]

Arrivals in the 19th and the 20th centuries

| European Emigrants 1800–1960 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Destination | Percent | ||

| United States | 70.0% | ||

| South America | 12.0% | ||

| Russian Siberia | 9.0% | ||

| Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa | 9.0% | ||

| Total | 100.0% | ||

Source:[58] | |||

| Destination | Years | Arrivals | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 1821–1932 | 32,244,000 | [56] |

| Argentina | 1856–1932 | 6,405,000 | [56] |

| Canada | 1831–1932 | 5,206,000 | [56] |

| Brazil | 1818–1932 | 4,431,000 | [56] |

| Australia | 1821–1932 | 2,913,000 | [56] |

| Cuba | 1901–1931 | 857,000 | [56] |

| South Africa | 1881–1932 | 852,000 | [56] |

| Chile | 1882–1932 | 726,000 | [56] |

| Uruguay | 1836–1932 | 713,000 | [56] |

| New Zealand | 1821–1932 | 594,000 | [56] |

| Mexico | 1911–1931 | 226,000 | [56] |

Legacy

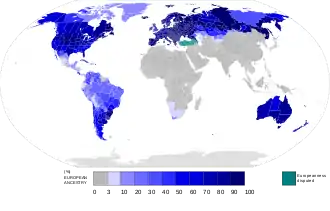

Distribution

After the Age of Discovery, different ethnic European communities began to emigrate out of Europe with particular concentrations in Australia, New Zealand, the United States, Canada, Argentina, Uruguay, Cuba, Costa Rica, Brazil, Chile, and Puerto Rico where they came to constitute a European-descended majority population.[58][59][60][61] It is important to note, however, that these statistics rely on identification with a European ethnic group in censuses, and as such are subjective (especially in the case of mixed origins). Nations and regions outside of Europe with significant populations:[62]

North America

Total European population—approximately 300,000,000

Canada

In the first Canadian census in 1871, 98.5% chose a European origin with it slightly decreasing to 96.3% declared in 1971.[63][64] In the 2016 census, 19,683,320 or 53.0% self-identified with a European ethnic origin, the largest being of British Isles origins (11,211,850). Individually, they are English (6,320,085), French (4,680,820), Scottish (4,799,005), Irish (4,627,000), German (3,322,405), Italian (1,587,965).[65] However, there is an undercount with 11,135,965 choosing "Canadian".[65]

United States

At the time of the first U.S. census in 1790, 80.7% of the American people self-identified as White, where it remained above that level, even reaching as high as 90% prior to the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. However, numerically it increased from 3.17 million (1790) to 199.6 million exactly two hundred years later (1990).[66] Today, European Americans are the largest panethnic group in the United States. The 2010 census data revealed that 72.4% of the population, or 223,800,000 people self-identified as White.[67]

Mexico

European Mexican - estimated by the government in 2010 as 47% of the population (56 million) using phenotypical traits (skin color) as the criteria.[8] If the criteria used is the presence of blond hair, it is 18%[68][69] - 23%.[70]

Caribbean and Central America

Cubans of European origin reached a peak of 74.3% or 3,553,312 of the total population in 1943.[71][72] Most recently, those self-identified as White made up 64.1% of the total population, according to the 2012 census.[73][74] They are predominately the descendants of early Spanish settlers, along with other Europeans including the Germans, English, French and Italians arriving later but in smaller numbers. However, after the mass exodus (particularly to the United States) resulting from the Cuban Revolution in 1959, the number of White Cubans actually residing in Cuba diminished.

The majority of White Dominicans are descendants from the first European settlers to arrive in Hispaniola and have ancestry of the Spanish and French who settled in the island during colonial times, as well as the Canary Islanders, Portuguese who settled in the 17th and 18th centuries. Many others also descend from Italians,[75][76] Dutch,[75][76] Germans,[75] Hungarians, Americans,[75][76] and other nationalities who have migrated between the 19th and 20th centuries.[75][76] According to a 2006 Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) survey, about 13.6% of the Dominican population (Circa 1.1 million) were reported as White.[77] The official 1960 Dominican Republic Census (the last census to ask a question on race) reported that 16.1% (489,850, 231,510 males, 258,070 females) of the total population, a slight increase over the 13.0% in 1950.[78][79] Currently Whites make up a significant minority in the country, but it is not possible to officially quantify their numbers because the National Institute of Statistics (INE) does not collect racial data because of the race taboo that originated after Rafael Trujillo’s dictatorship;[80] although the Central Electoral Board still collected racial data until 2014.[81] According to a 2011 survey by Latinobarómetro, 11% of the Dominicans surveyed identified themselves as White.[82] A study in 2012 “Cultura Política de la Democracia en la República Dominicana y en las Américas 2012: Hacia la Igualdad de Oportunidades” reported that 9.7% were self-identified as White.[83]

In Puerto Rico 75.8% of the population are estimated to be of White Puerto Ricans.[84]

South America

In Argentina 79% of the population or 38,900,000 are estimated to be of European descent and may include an unknown percentage of mestizos and mulattos.[85] Other sources[86] put 86.4% of the population.

The Falkland Islanders are mainly of European, especially British descent and can trace their heritage back 9 generations or 200 years. In 2016, the census showed that 42.9 percent were native born and 27.4 percent were born in the U.K. (the second largest birthplace) for a total of more than 70 percent.[87] The Falkland Islands were entirely unoccupied and were first claimed by Britain in 1765.[88] Settlers largely from Britain (especially Scotland and Wales arrived after the 1830s. The total population of then islands grew from a 287 estimate in 1851 to 3,200 in the most recent 2016 census.[89][90] The Origins of Falkland Islanders historically had a Gaucho presence.

In Peru the official 2017 census, 5.9% or (1.3 mil) 1,336,931 people 12 years of age and above self-identified their ancestors as White or European descent.[29]:214 This was the first time a question on race or ancestors had been asked since the 1940 census.[91] There were 619,402 (5.5%) males and 747,528 (6.3%) females. The region with the highest proportion of Peruvians with self-identified European or white origins was in the La Libertad Region (10.5%), Tumbes Region and Lambayeque Region (9.0%).[29]:214 Most are descendants of early Spanish settlers with substantial numbers of Italians and Germans.[92]

Australia and New Zealand

As at the 2016 census, it was estimated that around 58% of the Australian population were Anglo-Celtic Australians with 18% being of other European origins, a total of 76% for European ancestries as a whole.[93] As of 2016, the majority of Australians of European descent are of English 36.1%, Irish 11.0%, Scottish 9.3%, Italian 4.6%, German 4.5%, Greek 1.8% and Dutch 1.6%. A large proportion —33.5%— chose to identify as ‘Australian’, however the census Bureau has stated that most of these are of old Anglo-Celtic colonial stock.[94][95][96]

Europeans historically (especially Anglo-Celtic) and presently are still the largest ethnic group in New Zealand. Their proportion of the total New Zealand population has been decreasing gradually since the 1916 census where they formed 95.1 percent.[97] The 2018 official census had over 3 million people or 71.76% of the population were ethnic Europeans, with 64.1% choosing the New Zealand European option alone.[98]

Africa

South Africans of European descent were 4,586,838 or 8.9% of South Africa's population in the 2011 census.[99] They are predominantly descendants of Dutch, German, French Huguenots, English and other European settlers.[100][101] Culturally and linguistically, they are divided into the Afrikaans-speaking descendants of South Africa's original Dutch colonial population, known as Afrikaners, and members of a larger British diaspora in Africa. The first national census in South Africa was held in 1911 and showed a percentage peak of 21.4% or 1,276,242.[102] The population increased to its peak at 5,044,000 in 1990.[103] However, the number of White South African residents in their home country began gradually declining between 1990 and the mid-2000s as a result of increased emigration.[103]

White Ghanaians are descendants of mostly British settlers and Irish people who were forced to immigrate to Ghana. Some of these people are descendants of Portuguese, Dutch, Swedish, Danish, Norwegian, German, Italian, and Polish settlers.

Canary Islanders are the descendants of Spaniards who settled the Canary Islands. The Canarian people include long-tenured and new waves of Spanish immigrants, including Andalucians, Galicians, Castilians, Catalans, Basques and Asturians of Spain; and Portuguese, Italians, Dutch or Flemings, and French. As of 2019, 72.1% or 1,553,078 were native Canary islanders with a further 8.2% born in mainland Spain.[104] Many of European origins including those of Isleño (islander) lineage have also moved to the islands, such as those from Venezuela and Cuba. Presently there are 49,170 from Italy, 25,619 from Germany, United Kingdom (25,521) and others from Romania, France and Portugal.[105]

Asia

In Asia, European-derived populations, (specifically Russians), predominate in North Asia and some parts of Northern Kazakhstan.[106]

Anglo-Indians, Europeans in South Asia who are descended from colonizers. And Gaijin or Western/European/Caucasian residents in Japan.

Smaller Communities

Small communities of European, White American and White Australian expatriates in the Persian Gulf countries like Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar and the UAE; and in Aramco compounds in Saudi Arabia. Historically before 1970, small ethnic European (esp. Greek and Italian) enclaves were found in Egypt (Greeks in Egypt, Italian Egyptians) and Syria (Greeks in Syria). And Israel has a small non-Jewish (often Evangelical Christian) American community in a primarily ethnoreligious Jewish country.

Populations of European descent

- Albanian diaspora

- Austrian diaspora

- Belarusian diaspora

- Belgian diaspora

- Bosnian diaspora

- British diaspora

- Bulgarian diaspora

- Croatian diaspora

- Czech diaspora

- Danish diaspora

- Dutch diaspora

- Estonian diaspora

- Finnish diaspora

- French diaspora

- German diaspora

- Greek diaspora

- Hungarian diaspora

- Icelandic diaspora

- Irish diaspora

- Italian diaspora

- Latvian diaspora

- Lithuanian diaspora

- Maltese diaspora

- Macedonian diaspora

- North Caucasian diaspora

- Norwegian diaspora

- Polish diaspora

- Portuguese diaspora

- Romanian diaspora

- Russian diaspora

- Serbian diaspora

- Slovak diaspora

- Slovene diaspora

- Spanish diaspora

- Swedish diaspora

- Swiss diaspora

- Ukrainian diaspora

See also

References

- "Current World Population". Worldometers. July 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- Based on the figures given per official census results.

- "ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. December 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Pena, Sérgio D. J.; Di Pietro, Giuliano; Fuchshuber-Moraes, Mateus; Genro, Julia Pasqualini; Hutz, Mara H.; Kehdy, Fernanda de Souza Gomes; Kohlrausch, Fabiana; Magno, Luiz Alexandre Viana; Montenegro, Raquel Carvalho; Moraes, Manoel Odorico; Moraes, Maria Elisabete Amaral de; Moraes, Milene Raiol de; Ojopi, Élida B.; Perini, Jamila A.; Racciopi, Clarice; Ribeiro-Dos-Santos, Ândrea Kely Campos; Rios-Santos, Fabrício; Romano-Silva, Marco A.; Sortica, Vinicius A.; Suarez-Kurtz, Guilherme (2011). "The Genomic Ancestry of Individuals from Different Geographical Regions of Brazil is More Uniform Than Expected". PLOS ONE. 6 (2): e17063. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617063P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017063. PMC 3040205. PMID 21359226.

- http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/41/41131/tde-17122010-142628/pt-br.php

- Lizcano Fernández, Francisco (August 2005). "Composición Étnica de las Tres Áreas Culturales del Continente Americano al Comienzo del Siglo XXI" [Ethnic Composition of the Three Cultural Areas of the American Continent at the Beginning of the XXI Century]. Convergencia (in Spanish). 12 (38): 185–232.

- "Mexico: People; Ethnic groups". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- "21 de Marzo Día Internacional de la Eliminación de la Discriminación Racial" pag.7, CONAPRED, Mexico, 21 March. Retrieved on 28 April 2017.

- "Encuesta Nacional Sobre Discriminación en Mexico”, "CONAPRED", Mexico DF, June 2011. Retrieved on 28 April 2017.

- Ethnic Groups Worldwide: A Ready Reference Handbook. by David Levinson. Page 313. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1998. ISBN 1-57356-019-7

- "The World Factbook". cia.gov. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- https://genographic.nationalgeographic.com/reference-populations-next-gen/

- http://factsanddetails.com/russia/Minorities/sub9_3e/entry-5120.html

- "National Household Survey (NHS) Profile, 2011". 8 May 2013. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/document/publication/Leading%20for%20Change_Blueprint2018_FINAL_Web.pdf

- Bushnell, David (2010). Rex A. Hudson (ed.). Colombia: A Country Study. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-8444-9502-6.

- Schwartzman, Simon (2008). "Etnia, Condiciones de Vida y Discriminación" [Ethnicity, living conditions and discrimination]. In Valenzuela, Eduardo; Schwartzman, Simon; Scully, Timothy R.; Somma, Nicolas M.; Bihel, Andres (eds.). Vínculos, creencias e ilusiones: la cohesión social de los latinoamericanos (in Spanish). Uqbar Editores. pp. 61–72. ISBN 978-956-8601-17-1.

- "Resultado Basico del XIV Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda 2011" [Basic Results of the XIV National Population and Housing Census 2011] (PDF) (in Spanish). Caracas: National Institute of Statistics of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. 9 August 2012. p. 14. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "Demográficos: Censos de Población y Vivienda: Población Proyectada al 2016 - Base Censo 2011" [Demographics: Population and Housing Censuses: Population Projected to 2016 - Census Base 2011] (in Spanish). National Institute of Statistics. Retrieved 1 March 2017: adaption of the 42.2% white people from the census with current estimates

- "Ethnic groups". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- The World Factbook

- "Census 2011 Census in brief, Report No. 03-01-41" (PDF). Statistics South Africa. 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- "Численность населения Республики Казахстан по отдельным этносам на начало 2020 года". Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- "Cultural diversity". 2013 Census QuickStats about national highlights. Statistics New Zealand. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- Cabella, Wanda; Mathías Nathan; Mariana Tenenbaum (December 2013). Juan José Calvo (ed.). Atlas sociodemográfico y de la desigualdad del Uruguay, Fascículo 2: La población afro-uruguaya en el Censo 2011: Ancestry [Atlas of socio-demographics and inequality in Uruguay, Part 2: The Afro-Uruguayan population in the 2011 Census] (PDF) (in Spanish). Uruguay National Institute of Statistics. ISBN 978-9974-32-625-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 February 2014.

- 2010 Census Data. "2010 Census Data". 2010.census.gov. Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censo del Ecuador INEC.

- INE- Caracterización estadística República de Guatemala 2012 Retrieved, 2015/04/17.

- "Perú: Perfil Sociodemográfico" (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- https://www.indexmundi.com/nicaragua/demographics_profile.html

- https://www.france24.com/en/20131031-angola-portugal-row-investigation-fortune-business-trade

- https://thisisafrica.me/politics-and-society/race-relations-angola/

- https://www.news24.com/news24/africa/news/namibia-vows-to-change-status-quo-of-white-farm-ownership-20191208

- Philip Jenkins, from "The Christian Revolution," in The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity, Oxford University Press, 2002.

- The use of the term "diaspora" in reference to people of European national or ethnic origins is contested and debated- Diaspora and transnationalism : concepts, theories and methods. Bauböck, Rainer., Faist, Thomas, 1959-. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. 2010. ISBN 9789089642387. OCLC 657637171.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "To Make America": European Emigration in the Early Modern Period edited by Ida Altman, James P. P. Horn (Page: 3 onwards)

- De Lazzari, Chiara; Bruno Mascitelli (2016). "Migrant "Assimilation" in Australia: The Adult Migrant English Program from 1947 to 1971". In Bruno Mascitelli; Sonia Mycak; Gerardo Papalia (eds.). The European Diaspora in Australia: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-4438-9419-7. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- "European Migration and Imperialism". historydoctor.net. Archived from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

The population of Europe entered its third and decisive stage in the early eighteenth century. Birthrates declined, but death rates also declined as the standard of living and advances in medical science provided for longer life spans. The population of Europe including Russia more than doubled from 188 million in 1800 to 432 million in 1900. From 1815 through 1932, sixty million people left Europe, primarily to "areas of European settlement," in North and South America, Australia, New Zealand and Siberia. These populations also multiplied rapidly in their new habitat; much more so than the populations of Africa and Asia. As a result, on the eve of World War I (1914), 38 percent of the world's total population was of European ancestry. This growth in population provided further impetus for European expansion, and became the driving force behind emigration. Rising populations put pressure on land, and land hunger and led to "land hunger." Millions of people went abroad in search of work or economic opportunity. The Irish, who left for America during the great Potato famine, were an extreme but not unique example. Ultimately, one third of all European migrants came from the British Isles between 1840 and 1920. Italians also migrated in large numbers because of poor economic conditions in their home country. German migration also was steady until industrial conditions in Germany improved when the wave of migration slowed. Less than one half of all migrants went to the United States, although it absorbed the largest number of European migrants. Others went to Asiatic Russia, Canada, Argentina, Brazil, Australia and New Zealand.

- Pour une approche démographique de l'expansion coloniale de l'Europe Bouda Etemad Dans Annales de démographie historique 2007/1 (n° 113), pages 13 à 32

- Jerry H. Bentley, Herbert F. Ziegler, "Traditions and Encounters, 2/e," Chapter 10: "Mediterranean Society: The Greek Phase" Archived 2012-03-06 at the Wayback Machine (McGraw-Hill, 2003)

- Hellenistic Civilization Archived July 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Menander became the ruler of a kingdom extending along the coast of western India, including the whole of Saurashtra and the harbour Barukaccha. His territory also included Mathura, the Punjab, Gandhara and the Kabul Valley", Bussagli p101

- John Pike. "Failaka Island". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Liberal states and the freedom of movement : selective borders, unequal mobility. Mau, Steffen, 1968-. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. 2012. ISBN 9780230277847. OCLC 768167292.CS1 maint: others (link)

- MacIas, Rosario Marquez; MacÍas, Rosario Márquez (1995). La emigración española a América, 1765-1824. ISBN 9788474688566.

- (Levy & Vasques 2014, p. 250)

- 1944-, Francis, R. D. (R. Douglas) (1988). Origins : Canadian history to Confederation. Jones, Richard, 1943-, Smith, Donald B. Toronto: Holt, Rinehart and Winston of Canada. ISBN 978-0039217051. OCLC 16577780.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Galenson 1984: 1

- Charles II, 1679: An Act for the better secureing the Liberty of the Subject and for Prevention of Imprisonments beyond the Seas., Statutes of the Realm: Volume 5, 1628–80, pp 935–938. Great Britain Record Commission, (1819)

- Donoghue, John (October 2013). "Indentured Servitude in the 17th Century English Atlantic: A Brief Survey of the Literature: Indentured Servitude in the 17th Century English Atlantic". History Compass. 11 (10): 893–902. doi:10.1111/hic3.12088.

- Tomlins, Christopher (February 2001). "Reconsidering Indentured Servitude: European Migration and the Early American Labor Force, 1600–1775". Labor History. 42 (1): 5–43. doi:10.1080/00236560123269. S2CID 153628561.

- Gary Nash, The Urban Crucible: The Northern Seaports and the Origins of the American Revolution (1979) p 15

- Boris Fautos – Fazer a América: a imigração em massa para a América Latina."

- Cánovas, Marília D. Klaumann (2004). "A grande emigração européia para o Brasil e o imigrante espanhol no cenário da cafeicultura paulista: aspectos de uma (in)visibilidade" [The great European immigration to Brazil and immigrants within the Spanish scenario of the Paulista coffee plantations: one of the issues (in) visibility]. Sæculum (in Portuguese). 11: 115–136.

- Blanca Sánchez-Alonso (2005). "European Immigration into Latin America, 1870-1930" (PDF). docentes.fe.unl.pt. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2008.

- Samuel L. Baily; Eduardo José Míguez (2003). Mass Migration to Modern Latin America. Rowman & Littlefield. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-8420-2831-8. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- Baily, Samuel L.; Míguez, Eduardo José, eds. (2003). Mass Migration to Modern Latin America. Wilmington, Delaware: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8420-2831-8. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- World Civilizations: Volume II: Since 1500 By Philip J. Adler, Randall L. Pouwels

- Francisco Hernández Delgado; María Dolores Rodríguez Armas (2010). "La emigración de Lanzarote y sus causas". Archivo Histórico Municipal de Teguise (www.archivoteguise.es) (in Spanish). Teguise, Lanzarote, Canary Islands: Departamento de Cultura y Patrimonio, Ayuntamiento de Teguise. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- Ember et al 2004, p. 47.

- Marshall 2001, p. 254.

- Ethnic groups by country. Statistics (where available) from CIA Factbook.

- Ethnic origins Census of Canada (Page: 17)

- Table 1: Population by Ethnic Origin, Canada, 1921-1971 Page: 2

- Census Profile, 2016 Census - Ethnic origin population

- "Official census statistics of the United States race and Hispanic origin population" (PDF). US Statistics Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 February 2010.

- "Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010 Census Briefs" (PDF). US Census Bureau. March 2011. Archived from the original on 5 May 2011. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- "Stratification by Skin Color in Contemporary Mexico", Jstor org, available creating a free account , Retrieved on 27 January 2018.

- "Admixture in Latin America: Geographic Structure, Phenotypic Diversity and Self-Perception of Ancestry Based on 7,342 Individuals" table 1, Plosgenetics, 25 September 2014. Retrieved on 9 May 2017.

- Ortiz-Hernández, Luis; Compeán-Dardón, Sandra; Verde-Flota, Elizabeth; Flores-Martínez, Maricela Nanet (April 2011). "Racism and mental health among university students in Mexico City". Salud Pública de México. 53 (2): 125–133. doi:10.1590/s0036-36342011000200005. PMID 21537803.

- Cifras censales comparadas, 1899 - 1953 | P.189

- Revolutionizing Romance: Interracial Couples in Contemporary Cuba - By Nadine T Fernandez

- "2012 Cuban Census". One.cu. 28 April 2006. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- Grupo Copesa (8 November 2013). "Censo en Cuba concluye que la población decrece, envejece y se vuelve cada vez más mestiza". latercera.com.

- Zeller, Neicy Milagros (1977). "Puerto Plata en el siglo XIX". Estudios Dominicanos (in Spanish). eme eme. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- Ventura Almonte, Juan. "Presencia de ciudadanos ilustres en Puerto Plata en el siglo XIX" (PDF) (in Spanish). Academia Dominicana de la Historia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- "La variable étnico racial en los censos de población en la República Dominicana" [The ethnic-racial variables in the population censuses in the Dominican Republic] (PDF) (in Spanish). Dominican Republic Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- "Cuarto censo nacional de población, 1960". Oficina Nacional del Censo. 1966. p. 32 (cuadro 6). Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- "La variable étnico racial en los censos de población en la República Dominicana" [The ethnic-racial variables in the population censuses in the Dominican Republic] (PDF) (in Spanish). Dominican Republic Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- Frank Moya Pons (2010). Historia de la República Dominicana (in Spanish). 2. Santo Domingo: CSIC. pp. 50–51. ISBN 9788400092405. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- Néstor Medrano; Ramón Pérez Reyes (23 April 2014). "La JCE acelera cedulación en instituciones del país" (in Spanish). Listín Diario. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

Entre las novedades del nuevo documento no se establece como se hacía anteriormente el color de la piel de la persona, ya que, la misma fotografía consigna ese elemento.

- "Informe Latinobarómetro 2011" (in Spanish). p. 58. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- "Afro Alianza Dominicana "Desarrollo desde la Identidad"" (PDF). 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- "Puerto Rico 2010 Profile" (PDF). Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- Argentina: People: Ethnic Groups. World Factbook of CIA

- Ben Cahoon. "Argentina". worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- "2016 Falkland Island census report" (PDF). Falklandislandstimeline. p. 28. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- "Our People. Local life, traditions and services on the Islands". Falklands.gov.fk. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- "Falkland Island census data tables". Fig.gov.fk. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- "2016 Falkland Island census report" (PDF). Falklandislandstimeline. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Valdivia, Néstor (2011). El uso de categorías étnico/raciales en censos y encuestas en el Perú: balance y aportes para una discusión [The use of ethnic / racial categories in censuses and surveys in Peru: balance and contributions for a discussion] (in Spanish). GRADE Group for the Analysis of Development. ISBN 978-9972-615-57-3.

- Valdivia, Néstor (2011). El uso de categorías étnico/raciales en censos y encuestas en el Perú: balance y aportes para una discusión [The use of ethnic / racial categories in censuses and surveys in Peru: balance and contributions for a discussion] (in Spanish). GRADE Group for the Analysis of Development. ISBN 978-9972-615-57-3.

- "Australian Human Rights commission 2018" (PDF). 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics has stated that most who list "Australian" as their ancestry are part of the "Anglo-Celtic" group. "Feature Article - Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Australia (Feature Article)". January 1995. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- "THE ANCESTRIES OF AUSTRALIANS Census of Population and Housing: Reflecting Australia - Stories from the Census, 2016". abs.gov.au. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- "Census of Population and Housing: Reflecting Australia - Ancestry 2016". abs.gov.au. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- "Historical and statistical survey (P. 18)". Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- "2018 Census totals by topic – national highlights". Stats NZ. 23 September 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- "Census 2011 Census in brief, Report No. 03-01-41" (PDF). Statistics South Africa. 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Kristin Henrard (2002). Minority Protection in Post-Apartheid South Africa: Human Rights, Minority Rights, and Self-Determination. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-275-97353-7.

- James L. Gibson; Amanda Gouws (2005). Overcoming Intolerance in South Africa: Experiments in Democratic Persuasion. Cambridge University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-521-67515-4.

- Kriger, Robert; Kriger, Ethel (1997). Afrikaans Literature: Recollection, Redefinition, Restitution. Amsterdam: Rodopi BV. pp. 75–78. ISBN 978-9042000513.

- "Population of South Africa by population group" (PDF). Dammam: South African Department of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries. 2004. Archived from the original on 28 February 2005. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- "Estadística del Padrón Continuo a 1 de enero de 2019. Datos a nivel nacional, comunidad autónoma y provincia". Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- Canarias gana en un año 24.905 habitantes, el 66% de otros países Canarias7.es. Retrieved 5 October 2019

- Hill, Fiona (23 February 2004). "Russia — Coming In From the Cold?". The Globalist. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011.