White Puerto Ricans

White Puerto Ricans are Puerto Ricans who are of predominantly European descent. As of the 2010 U.S. census, people who self-identified as White constituted the majority in Puerto Rico, making up 75.8% of the population. People who identified themselves as being of mixed-race origin, predominantly of European and West African ancestry, constitute 3.3% of the population.[2][1] However, despite 75% of Puerto Ricans identifying as white, only about 25% are of pure European ancestry, with many self-identified White Puerto Ricans also having high amounts of West African and Native Taino blood, a cultural practice dating back to the mid 1800s Regla del Sacar law, opposite of the US One-drop rule.[3][4]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2,825,100[1] 75.8% of the total population (2010) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Throughout Puerto Rico | |

| Languages | |

| Spanish • English | |

| Religion | |

| Catholicism • Protestantism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| White Latin Americans, White Hispanic and Latino Americans, Puerto Rican Americans, White Cubans, White Dominicans |

Aside from Spanish—largely Canarian—settlers, additional Europeans of many families from France, the United Kingdom, Portugal, Italy, Germany, Ireland, among others, immigrated to Puerto Rico during Spain's five-hundred year-long occupation of the island, particularly during the 1800s due to the Royal Decree of Graces of 1815, where Spain encouraged and allowed immigration from all European countries to Puerto Rico.[5][6][7][8][9] Also during the 1800s, many whites from former Spanish colonies settled in Puerto Rico after their homeland gained independence, especially from nearby Dominican Republic and Venezuela. Since the modern era, Puerto Rico has been receiving moderate numbers of white immigrants from the mainland United States, Spain, Israel, Lebanon, as well as many other countries in Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa, as well as other White Latin Americans from other countries in the region such as Cuba and Colombia.[10][11]

Population history

An early Census on the island was conducted by Governor Lieutenant General Francisco Manuel de Landó in 1530.[12] An exhaustive 1765 census was taken by Lieutenant General Alexander O'Reilly which (according to some sources) showed 17,572 whites out of a total population of 44,883.[13][14] The censuses from 1765 to 1887 were taken by the Spanish government who conducted at irregular intervals. The 1899 census was taken by the War Ministry of the United States. Since 1910 Puerto Rico has been included in every decennial census taken by the United States.

| European / white population 1530 - 2010 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Population | % of Puerto Rico | Ref(s) | Year | Population | % of Puerto Rico | Ref(s) |

| 1530 | 333a, 426b | 8.0-10.0 | [15][16] | 1887 | 474,933 | 59.5 | [17] |

| 1765 | 17,572 | - | [13] | 1897 | 573,187 | 64.3 | [17] |

| 1775 | 30,709 | 40.4 | [18] | 1899 | 589,426 | 61.8 | [17] |

| 1787 | 46,756 | 45.5 | [18] | 1910 | 732,555 | 65.5 | [19] |

| 1802 | 78,281 | 48.0 | [17] | 1920 | 948,709 | 73.0 | [19] |

| 1812 | 85,662 | 46.8 | [17] | 1930 | 1,146,719 | 74.3 | [19] |

| 1820 | 102,432 | 44.4 | [17] | 1940 | 1,430,744 | 76.5 | [20] |

| 1827 | 150,311 | 49.7 | [17] | 1950 | 1,762,411 | 79.7 | [20] |

| 1830 | 162,311 | 50.1 | [17] | 2000 | 3,064,862 | 80.5 | [21] |

| 1836 | 188,869 | 52.9 | [17] | 2010 | 2,825,100 | 75.8 | [22] |

| 1860 | 300,406 | 51.5 | [17] | ||||

| 1877 | 411,712 | 56.3 | [17] | ||||

| Source: Official census statistics. | |||||||

Spain

Puerto Rico was a Spanish Overseas Province for nearly 400 years. The bulk of Puerto Ricans' European ancestry is from Spain. In 1899, one year after the United States invaded and took control of the island, 61.8% of people were identified as White. In the 2010 United States Census the total of Puerto Ricans that identified as White was 75.8%.[6][23] The European heritage of Puerto Ricans comes primarily from one source: Spaniards (including Canarians, Catalans, Castilians, Galicians, Asturians, and Andalusians) and Basques. Though, the Canary Islands of Spain has had the most influence on Puerto Rico, and is where most Puerto Ricans can trace their ancestry.[24][25][26][27] It is estimated up to 82% of persons in certain parts of Puerto Rico descend in part from Canarian people.[25][28] The table shows that in the twentieth century, the foreign-born made up a very small percentage of the total population of the Island. However, in 1910 people born in Europe composed 75.3% of the total foreign-born population, with Spain alone making up 60.9%.[29]

Canary Islander influence

The first wave of Canarian migration to Puerto Rico seems to be in 1695, followed by others in 1714, 1720, 1731, and 1797. The number of Canarians that immigrated to Puerto Rico in the first three centuries of Iberian rule is not known to any degree of precision. However, Dr. Estela Cifré de Loubriel and other scholars of the Canarian migration to America, such as Dr. Manuel González Hernández of the University of La Laguna, Tenerife, agree that they formed the bulk of the jíbaro, or white peasant stock, of the mountainous interior of the island.[24]

The Isleños increased their commercial traffic and immigration to the two remaining Spanish colonies in America, Puerto Rico and Cuba. Even after the Spanish–American War of 1898, Canarian immigration to the Americas continued. Successive waves of Canarian immigration continued to arrive in Puerto Rico, where entire villages were founded by relocated islanders.[30]

| European-born population in Puerto Rico[29][31] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Spain | Italy | France | Germany | UK | Other Europe | |

| 1899 | 7,690 | . | . | . | . | . | |

| 1910 | 6,630 | 362 | 681 | 192 | 313 | 387 | |

| 1920 | 4,975 | 233 | 580 | 94 | 183 | 129 | |

| 1930 | 3,506 | 166 | 367 | 91 | 137 | 112 | |

| 1940 | 2,532 | 118 | 224 | 98 | 138 | 180 | |

| 1950 | 2,851 | 120 | 222 | 126 | 123 | 302 | |

| 1960 | 2,558 | . | . | . | . | . | |

| 1970 | 4,120 | . | . | . | . | . | |

| 1980 | 5,200 | . | . | . | . | . | |

| 1990 | 4,579 | . | . | . | . | . | |

| 2000 | 3,800 | . | . | . | . | . | |

| 2010 | 2,676 | - | - | - | - | ||

In the 1860s, Canarian immigration to America took place at the rate of over 2,000 per year, at a time when the total island population was 237,036. In the two-year period 1885–1886, more than 4,500 Canarians emigrated to Spanish possessions, with only 150 to Puerto Rico. Between 1891 and 1895 Canarian immigrants to Puerto Rico numbered 600. These are official figures; if illegal or concealed emigration is taken into account, the numbers may be much larger.[32]

The Canarian cultural influence in Puerto Rico is one of the most important components in that many villages were founded by these immigrants, starting in 1493 until 1890 and beyond. Many Spaniards, especially Canarians, chose Puerto Rico because of its Hispanic ties and relative proximity in comparison with other former Spanish colonies. They searched for security and stability in an environment similar to that of the Canary Islands and Puerto Rico was the most suitable. This began as a temporary exile which became a permanent relocation and the last significant wave of Spanish or European migration to Puerto Rico.[33][32]

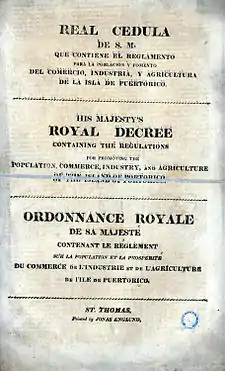

Royal Decree of Graces of 1815

By 1825, the Spanish Empire had lost all of its territories in the Americas with the exception of Cuba and Puerto Rico. These two possessions, however, had been demanding more autonomy since the formation of pro-independence movements in 1808. Realizing that it was in danger of losing its two remaining Caribbean territories, the Spanish Crown revived the Royal Decree of Graces of 1815.

The decree was printed in three languages—Spanish, French, and English—intending to attract mainland Spaniards and other Europeans, with the hope that the independence movements would lose their popularity and strength with the arrival of new settlers.

Under the Spanish Royal Decree of Graces, immigrants were granted land and initially given a "Letter of Domicile" after swearing loyalty to the Spanish Crown and allegiance to the Catholic Church. After five years they could request a "Letter of Naturalization" that would make them Spanish subjects. The Royal Decree was intended for non-Hispanic Europeans and not Asians nor people that were not Christian.

In 1897, the Spanish Cortes also granted Puerto Rico a Charter of Autonomy, which recognized the island's sovereignty and right to self-government. By April 1898, the first Puerto Rican legislature was elected and called to order.

Corsica

Hundreds of Corsicans and their families immigrated to Puerto Rico from as early as 1830, and their numbers peaked in the early 1900s. The first Spanish settlers settled and owned the land in the coastal areas, the Corsicans tended to settle the mountainous southwestern region of the island, primary in the towns of Adjuntas, Lares, Utuado, Ponce, Coamo, Yauco, Guayanilla and Guánica. However, it was Yauco whose rich agricultural area attracted the majority of the Corsican settlers. The three main crops in Yauco were coffee, sugar cane and tobacco. The new settlers dedicated themselves to the cultivation of these crops and within a short period of time some were even able to own and operate their own grocery stores. However, it was with the cultivation of the coffee bean that they would make their fortunes. The descendants of the Corsican settlers were also to become influential in the fields of education, literature, journalism and politics.[34]

Today the town of Yauco is known as both the "Corsican Town" and "The Coffee Town". There's a memorial in Yauco with the inscription, "To the memory of our citizens of Corsican origin, France, who in the C19 became rooted in our village, who have enriched our culture with their traditions and helped our progress with their dedicated work - the municipality of Yauco pays them homage." The Corsican element of Puerto Rico is very much in evidence, Corsican surnames such as Paoli, Negroni and Fraticelli are common.[35]

France

The French immigration to Puerto Rico began as a result of the economic and political situations which occurred in various places such as Louisiana (United States) and Saint-Domingue (Haiti). Upon the outbreak of the French and Indian War, also known as the Seven Years' War (1754–1763), between the Kingdom of Great Britain and its North American Colonies against France, many of the French settlers fled to Puerto Rico.[36] French immigration from mainland France and its territories to Puerto Rico was the largest in number, second only to Spanish immigrants and today a great number of Puerto Ricans can claim French ancestry; 16 percent of the surnames on the island are either French or French-Corsican.[34]

Their influence in Puerto Rican culture is very much present and in evidence in the island's cuisine, literature and arts.[37] Their contributions can be found, but are not limited to, the fields of education, commerce, politics, science and entertainment.

Germany

.jpg.webp)

German immigrants arrived in Puerto Rico from Curaçao and Austria during the early 19th century. Many of these early German immigrants established warehouses and businesses in the coastal towns of Fajardo, Arroyo, Ponce, Mayaguez, Cabo Rojo and Aguadilla. One of the reasons that these businessmen established themselves in the island was that Germany depended mostly on Great Britain for such products as coffee, sugar and tobacco. By establishing businesses dedicated to the exportation and importation of these and other goods, Germany no longer had to pay the high tariffs which the English charged them. Not all of the immigrants were businessmen; some were teachers, farmers and skilled laborers.[38]

In Germany the European Revolutions of 1848 in the German states erupted, leading to the Frankfurt Parliament. Ultimately, the rather non-violent "revolution" failed. Disappointed, many Germans immigrated to the Americas, including Puerto Rico, and were dubbed the Forty-Eighters. The majority of these came from Alsace-Lorraine, Baden, Hesse, Rheinland and Württemberg.[39] German immigrants were able to settle in the coastal areas and establish their businesses in towns such as Fajardo, Arroyo, Ponce, Mayagüez, Cabo Rojo and Aguadilla. Those who expected free land under the terms of the Spanish Royal Decree, settled in the central mountainous areas of the island in towns such as Adjuntas, Aibonito and Ciales among others. They made their living in the agricultural sector and in some cases became owners of sugar cane plantations. Others dedicated themselves to the fishing industry.[40]

In 1870, the Spanish Courts passed the Acta de Culto Condicionado (Conditional Cult Act), a law granting the right of religious freedom to all those who wished to worship another religion other than the Catholic religion. The Anglican Church, the Iglesia Santísima Trinidad, was founded by German and English immigrants in Ponce in 1872.[40]

By the beginning of the 20th century, many of the descendants of the first German settlers had become successful businessmen, educators, and scientists and were among the pioneers of Puerto Rico's television industry. Among the successful businesses established by the German immigrants in Puerto Rico were Mullenhoff & Korber, Frite, Lundt & Co., Max Meyer & Co. and Feddersen Willenk & Co. Korber Group Inc., one of Puerto Rico's largest advertising agencies, was founded by the descendants of William Korber.[41]

Ireland

From the 16th to the 19th century, there was considerable Irish immigration to Puerto Rico, for a number of reasons. During the 16th century many Irishmen, who were known as "Wild Geese", fled the English Army and joined the Spanish Army. Some of these men were stationed in Puerto Rico and remained there after their military service to Spain was completed.[42] During the 18th century men such as Field Marshal Alejandro O'Reilly and Colonel Tomas O'Daly were sent to the island to revamp the capital's fortifications.[43][44] O'Reilly was later appointed governor of colonial Louisiana in 1769 where he became known as "Bloody O'Reilly".[45] Irish immigrants played an instrumental role in the island's economy. One of the most important industries of the island was the sugar industry. Besides Tomás O'Daly, whose plantation was a success, other Irishmen became successful businessmen in this industry, among them Miguel Conway, who owned a plantation in the town of Hatillo and Juan Nagle whose plantation was located in Río Piedras. Puerto Ricans of Irish descent also played an instrumental role in the development of the island's tobacco industry. Miguel Conboy is credited with being the founder of the tobacco trade in Puerto Rico and the Quinlan family established two tobacco plantations, one in the town of Toa Baja and the other in Loíza.[46]

The Irish element in Puerto Rico is very much in evidence. Their contributions to Puerto Rico's agricultural industry and to the field of politics and education are highly notable.[47]

Jews

Even though the first Jews who arrived and settled in Puerto Rico were "Crypto-Jews" or "secret Jews", the Jewish community did not flourish on the island until after the Spanish–American War. Jewish-American soldiers were assigned to the military bases in Puerto Rico and many chose to stay and live on the island. Large numbers of Jewish immigrants began to arrive in Puerto Rico in the 1930s as refugees from Nazi occupied Europe. The majority settled in the island's capital, San Juan, where in 1942 they established the first Jewish Community Center of Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico is home to the largest and wealthiest Jewish community in the Caribbean with almost 3,000 Jewish inhabitants.[48] Puerto Rican Jews have made many contributions to the Puerto Rican way of life. Their contributions can be found in, but are not limited to, the fields of education, commerce and entertainment. Among the many successful businesses which they have established are Supermercados Pueblo (Pueblo Supermarkets), Almacenes Kress (clothing store), Doral Bank, Pitusa and Me Salve.[49][50][51]

Other immigration sources

Other sources of European populations are Basques, Portuguese, Italians, French people, Scots, Dutch, English, Danes and Jews. Further sources include white populations originating from New World countries like the United States, the Dominican Republic[52] and Cuba.

Present day Puerto Rico

.jpg.webp)

By the middle of the 20th century, Puerto Rico was nearly 80% white, in part due to the Royal Decree of Graces of 1815, when the central government of Spain granted free land to mainland Spaniards and other European Catholics willing to settle in Puerto Rico.[6][23][56][57][58] Though most Puerto Ricans self identified as white only, many have varying degrees of Taino (Native Puerto Rican) ancestry as well. In 1802, the options available on the Census documents were either "black" or "white" and people were no longer able to indicate Indio on the census self identification, so they were no longer counted. Before that, in 1797, 2,312 had self-identified as Indio. Evidence suggests that some Taíno men and African women inter-married and lived in relatively isolated Maroon communities in the interior of the islands, where they evolved into a hybrid rural or campesino population with little or no interference from the Spanish authorities.[59]

Studies have shown that European ancestry is strongest on the west side of the island, African ancestry mostly found on the east, and consistent levels of Taino ancestry throughout the island.[60] In fact, even though 75% of Puerto Ricans self-identify as white only, it is estimated only about 25% are of nearly pure European ancestry with little to no non-European admixture.[61][62][63] As mentioned above, this is partly due to North African ancestry inherited from Spanish immigrants from the Canary Islands, and even moreso due to the white European/North African settler population in Puerto Rico reproducing with Native Tainos and black West African slaves.[64][65][66][67][68]

Population by Municipalities in the 2010 Census

The population who self-identified as white in the census by municipality is as follows:

- Adjuntas 93.1%

- Aguada 86.6%

- Aguadilla 83.0%

- Aguas Buenas 72.5%

- Aibonito 83.5%

- Añasco 82.0%

- Arecibo 84.5%

- Arroyo 53.5%

- Barceloneta 80.7%

- Barranquitas 86.0%

- Bayamón 78.3%

- Cabo Rojo 84.1%

- Caguas 76.1%

- Camuy 87.9%

- Canóvanas 61.2%

- Carolina 64.3%

- Cataño 70.7%

- Cayey 79.9%

- Ceiba 70.6%

- Ciales 89.5%

- Cidra 76.6%

- Coamo 76.8%

- Comerío 78.6%

- Corozal 85.4%

- Culebra 56.9%

- Dorado 69.5%

- Fajardo 64.8%

- Florida 90.4%

- Guánica 79.9%

- Guayama 68.2%

- Guayanilla 81.9%

- Guaynabo 79.4%

- Gurabo 72.5%

- Hatillo 87.3%

- Hormigueros 81.2%

- Humacao 66.1%

- Isabela 83.4%

- Jayuya 90.7%

- Juana Díaz 75.3%

- Juncos 71.7%

- Lajas 80.6%

- Lares 91.1%

- Las Marías 86.3%

- Las Piedras 70.5%

- Loíza 26.5%

- Luquillo 65.5%

- Manatí 81.8%

- Maricao 89.2%

- Maunabo 47.9%

- Mayagüez 78.7%

- Moca 89.5%

- Morovis 88.4%

- Naguabo 71.1%

- Naranjito 84.2%

- Orocovis 86.7%

- Patillas 61.7%

- Peñuelas 81.8%

- Ponce 82.0%

- Quebradillas 89.2%

- Rincón 85.7%

- Río Grande 61.9%

- Sabana Grande 85.3%

- Salinas 67.4%

- San Germán 83.4%

- San Juan 68.0%

- San Lorenzo 76.1%

- San Sebastián 88.5%

- Santa Isabel 73.0%

- Toa Alta 76.3%

- Toa Baja 70.2%

- Trujillo Alto 72.1%

- Utuado 92.7%

- Vega Alta 71.2%

- Vega Baja 77.3%

- Vieques 58.7%

- Villalba 82.1%

- Yabucoa 65.6%

- Yauco 83.0%

See also

References

- "Puerto Rico 2010 Profile" (PDF). Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- "CIA - The World Factbook -- Puerto Rico". CIA. Retrieved 2013-10-12.

- "35% of Puerto Rican Women Sterilized". Uic.edu. Archived from the original on April 30, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- Via, Mark; Gignoux, Christopher R.; Roth, Lindsey; Fejerman, Laura; Galander, Joshua; Choudhry, Shweta; Toro-Labrador, Gladys; Viera-Vera, Jorge; Oleksyk, Taras K.; Beckman, Kenneth; Ziv, Elad; Risch, Neil; González Burchard, Esteban; Nartínez-Cruzado, Juan Carlos (2011). "History Shaped the Geographic Distribution of Genomic Admixture on the Island of Puerto Rico". PLOS ONE. 6 (1): e16513. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...616513V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016513. PMC 3031579. PMID 21304981.

- Vincent, Ted (July 30, 2002). "Racial Amnesia — African Puerto Rico & Mexico: Emporia State University professor publishes controversial Mexican history". Stewartsynopsis.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- "How Puerto Rico Became White: An Analysis of Racial Statistics in the 1910 and 1920 Censuses" (PDF). Ssc.wisc.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 7, 2012. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- Duany, Jorge (2005). "Neither White nor Black: The Politics of Race and Ethnicity among Puerto Ricans on the Island and in the U.S. Mainland" (PDF). Max Webber, Social Sciences, Hunter College. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- "The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- "2010 Census Data". US Census Bureau. 2011. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011.

- "Officials and Employees of the City of San Juan de Puerto Rico (1897)". Rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- "1974 Analysis" (PDF). Rcsdigital.homestead.com. Retrieved 2017-08-02.

- "Historia de Puerto Rico" (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 17. Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- R. Haines, Michael; H. Steckel, Richard. "A Population History of North America". Retrieved August 30, 2020.

- "El crecimiento poblacional en Puerto Rico: 1493 al presente" (PDF). August 30, 2020.

- "El -Censo de Lando (1530)" (PDF). Sp.rcm.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- HISTORIA DE PUERTO RICO Page 17.

- Report on the census of Porto Rico, 1899 Census of "Porto Rico" (Old Spelling) Page 57.

- El crecimiento poblacional en Puerto Rico: 1493 al presente Archived 2015-10-03 at the Wayback Machine (Population of Puerto Rico 1493 - present)

- Puerto Rico Census of 1910, 1920 & 1930. (See page 136).

- The population of the United States and Puerto Rico See (page 53-26).

- Summary Population, Housing Characteristics. Puerto Rico: 2000 Census. (Page 52).

- Puerto Rico: 2010 - Summary Population and Housing Characteristics 2010 Census of Population and Housing.

- "2010.census.gov". 2010.census.gov. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- Hernández, Miguel. "Passenger - Canary Islands to Puerto Rico". Rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- "American Taíno: Puerto Rico's Canary Islands Connection". Americantaino.blogspot.com. 28 March 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- "St. Bernard Isleños : LOUISIANA'S SPANISH TREASURE". Losislenos.org. Archived from the original on 2015-02-03. Retrieved 2017-08-02.

- NTI. "LA EMIGRACIAN CANARIA A AMERICA A TRAVOS DE LA HISTORIA". Gobiernodecanarias.org. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- Las raíces isleñas de Mayagüez (in Spanish: The island roots of Mayagüez) by Federico Cedó Alzamora, Official Historian of Mayagüez.

- GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS Table 21.-NATIVITY AND COUNTRY OF BIRTH OF THE POPULATION, FOR PUERTO RICO, URBAN AND RURAL 1950, AND FOR PUERTO RICO, 1910 TO 1940

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-02-24. Retrieved 2014-10-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- PLACE OF BIRTH FOR THE FOREIGN-BORN POPULATION IN PUERTO RICO Archived 2020-02-14 at Archive.today Universe: Foreign-born population in Puerto Rico excluding population born at sea. 2010-2014 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates

- "THE SPANISH OF THE CANARY ISLANDS". Personal.psu.edu. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- "MANUEL MORA MORALES: Canarios en Puerto Rico. CANARIAS EMIGRACIÓN". YouTube. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- "Corsican immigration to Puerto Rico". rootsweb.com. Archived from the original on 28 October 2007. Retrieved July 31, 2007.

- Corsican Immigrants to Puerto Rico, retrieved July 31, 2007

- "レーシックが向いている人と向いていない人". Historicalpreservation.org. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- chefbrad (3 April 2008). "Puerto Rico: Recipes and Cuisine". Whats4eats.com. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- "Dr. Ursula Acosta: Genealogy: My Passion and Hobby". home.coqui.net. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- Breunig, Charles (1977), The Age of Revolution and Reaction, 1789–1850 (ISBN 0-393-09143-0)

- "La presencia germanica en Puerto Rico". Preb.com. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- Group

- "Irish and Scottish Military Migration to Spain". Trinity College Dublin. 2008-11-29. Retrieved 26 May 2008.

- Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña

- "The Celtic Connection". Archived from the original on August 13, 2006. Retrieved November 29, 2008.

- Alejandro O'Reilly 1725-1794 Archived 2008-12-05 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved November 29, 2008

- Irish and Puerto Rico, Retrieved November 29, 2008

- "Emerald Reflections Online". Angelfire.com. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- The Virtual Jewish History Tour Puerto Rico, Jewish Virtual Library, Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- Toppel, 84, supermarket mogul, philanthropist, Palm Beach Post, Retrieved January 9, 2009

- Puerto Rico Companies Archived 2005-05-03 at the Wayback Machine, Right Management, Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- Work hard and improve constantly. (Israel Kopel, president of Almacenes Pitusa) (Top 10 Business Leaders of Puerto Rico: 1991), Caribbean Business, Retrieved January 9, 2009

- Duany, Jorge (1992). "Caribbean Migration to Puerto Rico: A Comparison of Cubans and Dominicans" (PDF). The International Migration Review. 26 (1): 46–66. doi:10.1177/019791839202600103. JSTOR 2546936. PMID 12285046. S2CID 10506772.

- "Yo soy papa y mama a mis hijos". Vanity Fair (in Spanish). Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- Galaz, Mabel (November 4, 2011). "El gobierno concede a Ricky Martin la nacionalidad española para poder casarse". El País. Retrieved November 8, 2011.

- Martin, Ricky (November 2, 2010). Me. Penguin. ISBN 9781101475041. Retrieved April 8, 2020 – via Google Books.

- "Representation of racial identity among Puerto Ricans and in the u.s. mainland". Mona.uwi.edu. Archived from the original on 12 December 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- CIA World Factbook Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- Puerto Rico's Historical Demographics Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- Baracutei Estevez, Jorge (14 October 2019). "Meet the survivors of a 'paper genocide'". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- "Mapping Puerto Rican Heritage with Spit and Genomics". M.livescience.com. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- "How Puerto Rico Became White : An Analysis of Racial Statistics in the 1910 and 1920 Censuses" (PDF). Ssc.wisc.edu. Retrieved 2017-08-02.

- "Your Regional Ancestry: Reference Populations". Genographic.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- González Burchard, E; Borrell, LN; Choudhry, S; et al. (December 2005). "Latino populations: a unique opportunity for the study of race, genetics, and social environment in epidemiological research". Am J Public Health. 95 (12): 2161–8. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.068668. PMC 1449501. PMID 16257940.

- Pino-Yanes, María; Corrales, Almudena; Basaldúa, Santiago; Hernández, Alexis; Guerra, Luisa; Villar, Jesús; Flores, Carlos (2011). O'Rourke, Dennis (ed.). "North African Influences and Potential Bias in Case-Control Association Studies in the Spanish Population". PLOS ONE. 6 (3): e18389. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...618389P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018389. PMC 3068190. PMID 21479138.

- Fregel, Rosa; Pestano, Jose; Arnay, Matilde; Cabrera, Vicente M; Larruga, Jose M; González, Ana M (2009). "The maternal aborigine colonization of La Palma (Canary Islands)". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (10): 1314–24. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2009.46. PMC 2986650. PMID 19337312.

- Falcón in Falcón, Haslip-Viera and Matos-Rodríguez 2004: Ch. 6

- Juan C. Martínez Cruzado (2002). "The Use of Mitochondrial DNA to Discover Pre-Columbian Migrations to the Caribbean: Results for Puerto Rico and Expectations for the Dominican Republic" (PDF). Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology. ISSN 1562-5028. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-06-22. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 12 February 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2017.