European herring gull

The European herring gull (Larus argentatus) is a large gull, up to 66 cm (26 in) long. One of the best-known of all gulls along the shores of Western Europe, it was once abundant.[2] It breeds across Northern Europe, Western Europe, Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Scandinavia, and the Baltic states. Some European herring gulls, especially those resident in colder areas, migrate further south in winter, but many are permanent residents, e.g. in Ireland, Britain, Iceland, or on the North Sea shores. They have a varied diet, including fish, crustaceans, and dead animals, as well as some plants.

| European herring gull | |

|---|---|

| |

| Breeding-plumaged adult on Heligoland | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Laridae |

| Genus: | Larus |

| Species: | L. argentatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Larus argentatus Pontoppidan, 1763 | |

| |

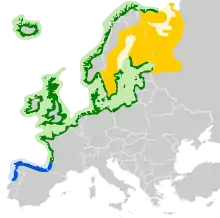

| Range of L. argentatus Breeding range Year-round range Wintering range | |

While herring gull numbers appear to have been harmed in recent years, possibly by fish population declines and competition, they have proved able to survive in human-adapted areas and can often be seen in towns acting as scavengers.

Taxonomy

Their scientific name is from Latin. Larus appears to have referred to a gull or other large seabird and argentatus means decorated with silver.[3]

The taxonomy of the herring gull/lesser black-backed gull complex is very complicated, with different authorities recognising between two and eight species.

This group has a ring distribution around the Northern Hemisphere. Differences between adjacent forms in this ring are fairly small, but by the time the circuit is completed, the end members, herring gull and lesser black-backed gull, are clearly different species. The terminal forms do not interbreed, though they coexist in the same localities.[4]

The Association of European Rarities Committees recognises six species:

- European herring gull, L. argentatus

- American herring gull, L. smithsonianus

- Caspian gull, L. cachinnans

- Yellow-legged gull, L. michahellis

- Vega gull, L. vegae

- Armenian gull, L. armenicus

Subspecies

- L. a. argentatus – Pontoppidan, 1763, the nominate form, sometimes known as the Scandinavian herring gull, breeds in Scandinavia and northwestern Russia. Northern and eastern populations migrate southwest in winter. It is a large, bulky gull with extensive white in the wingtips.

- L. a. argenteus – Brehm & Schilling, 1822, sometimes known as the Western European herring gull breeds in Western Europe in Iceland, the Faroes, Britain, Ireland, France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany. Many birds are resident while others make short-distance migratory journeys. It is smaller than L. a. argentatus with more black and less white in the wingtips and paler upper parts.

These taxa are classified as subspecies of Larus argentatus by some authorities such as the American Ornithologists' Union and Handbook of the Birds of the World. Others such as the Association of European Rarities Committees, British Ornithologists' Union, and the International Ornithological Union now regard them as one or two separate species.[5][6]

- L. (a.) smithsonianus, the American herring gull, breeds in Alaska, Canada, and the Northeast United States. Many birds migrate southwards in winter, reaching as far as Central America and the West Indies. Immature birds tend to be darker and more uniformly brown than European herring gulls and have a dark tail.

- L. (a.) vegae, the Vega gull, breeds in northeastern Siberia. It winters in Japan, Korea, eastern China, and Taiwan.

Several other gulls have been included in this species in the past, but are now normally considered separate, e.g. the yellow-legged gull (L. michahellis), the Caspian gull (L. cachinnans), the Armenian gull (L. armenicus) and Heuglin's gull (L. heuglini).

Description

The male European herring gull is 60–67 cm (24–26 in) long and weighs 1,050–1,525 g (2.315–3.362 lb), while the female is 55–62 cm (22–24 in) and weighs 710–1,100 g (1.57–2.43 lb). The wingspan can range from 125 to 155 cm (49 to 61 in).[7][8][9][10] Among standard measurements, the wing chord is 38 to 48 cm (15 to 19 in), the bill is 4.4 to 6.5 cm (1.7 to 2.6 in) and the tarsus is 5.3 to 7.5 cm (2.1 to 3.0 in).[8] Adults in breeding plumage have a grey back and upper wings and white head and underparts. The wingtips are black with white spots known as "mirrors". The bill is yellow with a red spot and a ring of bare yellow skin is seen around the pale eye. The legs are normally pink at all ages, but can be yellowish, particularly in the Baltic population, which was formerly regarded as a separate subspecies "L. a. omissus". Non-breeding adults have brown streaks on their heads and necks. Male and female plumage are identical at all stages of development, but adult males are often larger.[11]

Juvenile and first-winter birds are mainly brown with darker streaks and have a dark bill and eyes. Second-winter birds have a whiter head and underparts with less streaking and the back is grey. Third-winter individuals are similar to adults, but retain some of the features of immature birds such as brown feathers in the wings and dark markings on the bill. The European herring gull attains adult plumage and reaches sexual maturity at an average age of four years.[12]

_juvenile.jpg.webp) Juvenile, Portugal

Juvenile, Portugal Juvenile in first winter plumage

Juvenile in first winter plumage_second_winter.jpg.webp) Juvenile (second winter)

Juvenile (second winter) Juvenile (third winter)

Juvenile (third winter)_adult_non-breeding_plumage.jpg.webp) Adult (non-breeding plumage), Portugal

Adult (non-breeding plumage), Portugal

Yellow-legged variety

At least in the south-west part of the Baltic Sea and surrounding areas, the European herring gull (L. argentatus) actually can be seen with yellow legs. They are not considered as a subspecies, since they regularly breed with grey/flesh-coloured legged herring gulls. The offspring may get yellow or normal-coloured legs. They must not be confused with the in general yellow-legged gull (L. michahellis), which are more common in the Mediterranean area, but single birds may reach more northern seas.

_-_Omissus_-_Ystad-2020.jpg.webp)

Similar species

Adult European herring gulls are similar to ring-billed gulls, but are much larger, have pinkish legs, and a much thicker yellow bill with more pronounced gonys. First-winter European herring gulls are much browner, but second- and third-winter birds can be confusing since soft part colours are variable and third-year herring gull often show a ring around the bill. Such birds are most easily distinguished by the larger size and larger bill of European herring gull.

The European herring gull can be differentiated from the closely related, slightly smaller lesser black-backed gull by the latter's dark grey (not actually black) back and upper wing plumage and its yellow legs and feet.

The smaller silver gull is largely confined to Australia.

Voice

Their loud, laughing call is well known in the Northern Hemisphere, and is often seen as a symbol of the seaside in countries such as the United Kingdom. The European herring gull also has a yelping alarm call and a low, barking anxiety call. The most distinct and best known call produced by European herring gulls – which is shared with their American relative – is the raucous territorial 'long call', used to signal boundaries to other birds; it is performed by the gull initially with its head bowed, then raised as the call continues.[13]

European herring gull chicks and fledglings emit a distinctive, repetitive, high-pitched 'peep', accompanied by a head-flicking gesture when begging for food from or calling to their parents. Adult gulls in urban areas also exhibit this behaviour when fed by humans.

Behaviour

European herring gull flocks have a loose pecking order, based on size, aggressiveness, and physical strength. Adult males are usually dominant over females and juveniles in feeding and boundary disputes, while adult females are typically dominant when selecting their nesting sites.[12] Communication between these birds is complex and highly developed —employing both calls and body language. The warning sounds to chicks are the most obvious to interpret.

The warning to their chicks sounds almost like a bark from a small dog. If the danger closes in, the bark is repeated, and when very close, the warning is three quick barks. If a chick is "grounded", the bird makes itself appear bigger to intimidate the threat. If other adult birds are present, they will help in the same way. For instance, a person with a dog (or someone who chases the chick) may be attacked by many adult birds, even if just one chick is in danger.

The warning sound from a flying bird to a flock of fully fledged birds sounds very different. All kinds of gulls seemingly understand the "general alert warning sound" of all other gulls. Little doubt remains that the gull's screaming is a language for communication. It is limited to the present tense, but includes rather complex matters such as "follow me".

Two identical vocalizations can have very different (sometimes opposite) meanings. For example, it depends on the position of the head, body, wings, and tail relative to each other and the ground.

Unlike many flocking birds, European herring gulls do not engage in social grooming and keep physical contact between individuals to a minimum. Outside the male/female and parent/chick relationships, each gull attempts to maintain a respectful 'safe distance' from others of its kind. However, the bird must be considered a social bird that dislikes being alone, and fights mainly occur over food or to protect their eggs and chicks. If a few birds discover a piece of food, the first one to land by the food piece often unfolds its wings (together with a sound) to proclaim "this food is mine". This is very often opposed by another gull, and during a short fight, a third bird may grab the food while the two other are arguing. However, if much food is found, especially at a "dangerous location" (such as in the backyard of a tall building), the bird that discovered the food will call to other gulls close by (of any species). The first bird may dare to land, but waits before eating; the others then feel safe to land, and they eat. If a large feast is found at a safer location, the gull that discovers it calls to other gulls, but starts eating immediately. The conclusion is that if more food is available than one bird can eat, it shares the food with other gulls.

During the winter, large flocks can be seen at (snow-free) fields (agricultural or grass), especially if the ground has a high degree of moisture. At first sight, it the birds appear to be just standing there, but then on closer inspection, only their bodies are not moving; the birds actually are trampling the soil, most likely to trick worms to crawl closer to the surface of the soil.

During early spring and late autumn, many herring gulls feed heavily on earthworms, but they are very opportunistic birds that seem to have many sources of food. For instance in southern Scandinavia and northern Germany, this species recently has become the most common of all gulls, and the increase has mostly occurred in urban or suburban environments.

The great black-backed gull (L. marinus) was around 1900 as common as the herring gull in the mentioned parts, but has not increased as much (if at all), though some signs indicate the bigger gull has learned (adopted) some of the herring gull's behaviour within urban environments. Where the herring gull is breeding in coastal urban environments, the great black-backed gull seems to do the same, but in a lesser scale.

Herring gulls are good at producing all three eggs into flying birds. This means that at least one (often two) of the newly flying chicks loses both its parents within days after first flight. Some of these can later be seen in flocks of smaller gulls like the black-headed gull (Chroicocephalus ridibundus) or the common gull (L. canus). They are probably not welcomed in such flocks, but follow them for some months, anyway, and do thereby learn where to find food. Lonely juvenile herring gulls born in urban environments can also be seen staying for a some weeks close to outdoor restaurants and similar facilities, squeaking and begging for food from humans. By November or December, most juveniles have found other "flockmates", usually in areas near water.

The herring gull does not need swimming, but seems to enjoy all kind of waters, especially on hot summer days. It can only catch slow creatures, like small crabs, which it often drops from some altitude to crack them open. The bird has little real power in its jaws while biting, but it may "stab" with better strength. Fish on land, eggs of other birds, and helpless chicks of smaller ducks (and similar birds where the female is the only caretaker of up to 9 eggs and chicks) are about as much predator the bird gets. It is then far more successful as a scavenger. Like vultures, an adult bird can dig its whole head and neck into a dead rabbit, for instance. Although not always appreciated by mankind due to their droppings and screaming, the herring gull must be regarded as a "natural cleaner", and just as with crows, they help by keeping rats away from the surface in urban environment, not by killing rats, but by eating the potential rat food before the rats get the chance. Unlike real scavengers, herring gulls also eat most other things than meat, like wasted food of all kinds, from bread to human vomit. They seldom eat fresh fruit, but windfalls and rotten fruit seem more desired.

In cities, herring gulls have been witnessed attacking and killing feral pigeons.

The European herring gull has long been believed to have extremely keen vision in daylight and night vision equal or superior to that of humans;[14] however, this species is also capable of seeing ultraviolet light.[15] This gull also appears to have excellent hearing and a sense of taste that is particularly responsive to salt and acidity.[14]

Parasites of European herring gulls include the fluke Microphallus piriformes.

Distribution

Ireland: Copeland Bird Observatory, Co Down.[16]

Britain: Since 2009, herring gulls in the United Kingdom have been on the red list of birds of conservation concern,[17] including County Durham.[18]

Europe: Recorded from all the coasts of Europe including the Mediterranean and occasionally inland.[19]

Diet

These are omnivores and opportunists like most Larus gulls, and scavenge from garbage dumps, landfill sites, and sewage outflows, with refuse comprising up to half of the bird's diet. It also steals the eggs and young of other birds (including those of other gulls), as well as seeking suitable small prey in fields, on the coast or in urban areas, or robbing plovers or lapwings of their catches. European herring gulls may also dive from the surface of the water or engage in plunge diving in the pursuit of aquatic prey, though they are typically unable to reach depths greater than 1–2 m (3.3–6.6 ft) due to their natural buoyancy.[20] Despite their name, they have no special preference for herrings — in fact, examinations have shown that echinoderms and crustaceans comprised a greater portion of these gulls' stomach contents than fish, although fish is the principal element of regurgitations for nestlings.[21] European herring gulls can frequently be seen to drop shelled prey from a height to break the shell. In addition, the European herring gull has been observed using pieces of bread as bait with which to catch goldfish.[22] Vegetable matter, such as roots, tubers, seeds, grains, nuts, and fruit, is also taken to an extent.[12] Captive European herring gulls typically show aversion to spoiled meat or heavily salted food, unless they are very hungry. The gulls may also rinse food items in water in an attempt to clean them or render them more palatable before swallowing.[14]

European herring gulls may be observed rhythmically drumming their feet upon the ground for prolonged periods of time in a behaviour that superficially resembles Irish stepdancing, for the purpose of creating vibrations in the soil, driving earthworms to the surface, which are then consumed by the gull.[23] These vibrations are thought to mimic those of digging moles, eliciting a surface-escape behaviour from the earthworm, beneficial in encounters with this particular predator, which the European herring gull then exploits to its own benefit in a similar manner to human worm charmers.[24]

Whilst the European herring gull is fully capable (unlike humans) of consuming seawater, using specialized glands located above the eyes to remove excess salt from the body (which is then excreted in solution through the nostrils and drips from the end of the bill), it drinks fresh water in preference, if available.[12][21]

Courtship and reproduction

When forming a pair bond, the hen approaches the cock on his territory with a hunched, submissive posture, while making begging calls (similar to those emitted by young gulls). If the cock chooses not to attack her and drive her away, he responds by assuming an upright posture and making a mewing call. This is followed by a period of synchronised head-tossing movements, after which the cock then regurgitates some food for his prospective mate. If this is accepted, copulation follows. A nesting site is then chosen by both birds which is returned to in successive years.[12] European herring gulls are almost exclusively sexually monogamous and may pair up for life, provided the couple is successful in hatching their eggs.[20]

Two to four eggs, usually three, are laid on the ground or cliff ledges in colonies, and are defended vigorously by this large gull. The eggs are usually olive-brown in colour with dark speckles or blotches. They are incubated by both parents for 28–30 days. The chicks hatch with their eyes open, covered with fluffy down, and they are able to walk around within hours. Breeding colonies are preyed upon by great black-backed gulls, harriers, corvids and herons.

Juveniles use their beaks to peck at the red spot on the beaks of adults to indicate hunger. Parents then typically disgorge food for their offspring.[25] The young birds are able to fly 35–40 days after hatching and fledge at five or six weeks of age. Chicks are generally fed by their parents until they are 11–12 weeks old, but the feeding may continue for more than six months of age if the young gulls continue to beg. The male feeds the chick more often than the female before fledging, with the female more often feeding after fledging.[12]

Like most gulls, European herring gulls are long-lived, with a maximum age of 49 years recorded.[26] Raptors (especially owls, peregrine falcons, and gyrfalcons) and seals (especially grey seals) occasionally prey on the non-nesting adults.[20]

Mating

Mating On nest

On nest Chick with an egg in nest

Chick with an egg in nest Adult regurgitating food for its chicks

Adult regurgitating food for its chicks Adult feeding one of its chicks

Adult feeding one of its chicks

Interactions with humans

In the UK, the species, when taken as a whole, is declining significantly across the country, despite an increase in urban areas. The UK European herring gull population has decreased by 50% in 25 years[27] and it is protected by law: since January 2010, Natural England has allowed lethal control only with a specific individual licence that is available only in limited circumstances.[28] Natural England made the change following a public consultation[29] in response to the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds in 2009 placing the species on its 'Red List' of threatened bird species, affording it the highest possible conservation status.[30] (Previously, killing the species was allowed under a general licence obtainable by authorised persons (e.g. landowners or occupiers) under certain circumstances (e.g. to prevent serious damage to crops or livestock, to prevent disease, or to preserve public health or safety) without requiring additional permission beyond the general licence.[27])

The European herring gull is an increasingly common roof-nesting bird in urban areas of the UK, and many individual birds show little fear of humans. The Clean Air Act 1956 forbade the burning of refuse at landfill sites, providing the European herring gull with a regular and plentiful source of food. As a direct result, European herring gull populations in Britain skyrocketed. Faced with a lack of space at their traditional colonies, the gulls ventured inland in search of new breeding grounds. Dwindling fish stocks in the seas around Britain may also have been a significant factor in the gulls' move inland.

The gulls are found all year round in the streets and gardens of Britain, due to the presence of street lighting (which allows the gulls to forage at night), discarded food in streets, food waste contained in easy-to-tear plastic bin bags, food intentionally left out for other birds (or the gulls themselves), the relative lack of predators, and readily available, convenient, warm and undisturbed rooftop nesting space in towns and cities. Particularly large urban gull colonies (composed primarily of European herring gulls and lesser black-backed gulls) are now present in Cardiff, Bristol, Gloucester, Swindon, London, and Aberdeen.[31] to name but a few.

The survival rate for urban gulls is much higher than their counterparts in coastal areas, with an annual adult mortality rate less than 5%. Also, each European herring gull pair commonly rears three chicks per year. This, when combined with their long-lived nature, has resulted in a massive increase in numbers over a relatively short period of time and has brought urban-dwelling members of the species into conflict with humans.[31]

Once familiar with humans, urban European herring gulls show little hesitation in swooping down to steal food from the hands of humans, although a study conducted in 2019 demonstrated that the gulls are more averse to snatching food in proximity to humans if the experimenter made eye contact with the bird.[32] During the breeding season, the gulls also aggressively 'dive bomb' and attempt to strike with claws and wings (sometimes spraying faeces or vomit at the same time) at humans that they perceive to be a threat to their eggs and chicks —often innocent passers-by or residents of the buildings on which they have constructed their nests. Large amounts of gull excrement deposited on property and the noise from courting pairs and begging chicks in the summer is also considered to be a nuisance by humans living alongside the European herring gull.[31]

Nonlethal attempts to deter the gulls from nesting in urban areas have been largely unsuccessful. The European herring gull is intelligent and will completely ignore most 'bird-scaring' technology after determining that it poses no threat. Rooftop spikes, tensioned wires, netting, and similar are also generally ineffective against this species, as it has large, wide feet with thick, leathery skin, which affords the seagull excellent weight distribution and protection from sharp objects (the bird may simply balance itself on top of these obstacles with little apparent concern). If nests are removed and eggs are taken, broken, or oiled, the gulls simply rebuild and/or relay, or choose another nest site in the same area and start again.[31]

Man-made models of birds of prey placed on top of buildings are generally ignored by the gulls once they realise they are not real, and attempts to scare the gulls away using raptors are similarly ineffective. Although they are intimidated by birds of prey, European herring gulls, in addition to being social birds with strength in numbers, are large, powerful, and aggressive as individuals and are more than capable of fighting back against the potential predator, particularly if they consider their chicks to be at risk; in fact, the gulls may actually pose a greater threat to a raptor than vice versa.[33] European herring gulls are also naturally accustomed to predators (such as skuas and great black-backed gulls) living in the vicinity of their nest sites in the wild and are not particularly discouraged from breeding by their presence.[31]

Gallery

_Ystad-2017.jpg.webp)

Flying

Flying Standing atop a pole

Standing atop a pole Fledgling

Fledgling A sub-adult

A sub-adult In flight

In flight in flight

in flight In flight, facing

In flight, facing Preening

Preening

A flock of fledglings

A flock of fledglings Standing on rail

Standing on rail Drinking

Drinking Yawning

Yawning Close up, head plumage damaged and incomplete

Close up, head plumage damaged and incomplete Parent and chick

Parent and chick Standing

Standing Standing

Standing ID composite

ID composite_Ystad-2018.jpg.webp) Herring gull eating a flatfish.

Herring gull eating a flatfish.%252C_Amrum.jpg.webp) Screeching, North Frisian Islands Amrum

Screeching, North Frisian Islands Amrum Facing the wind

Facing the wind top of wings visible

top of wings visible

References

- Symes, A. (2015). "Larus argentatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T62030608A83943414. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T62030608A83943414.en.

- Gilliard, E. Thomas (1958). Living Birds of the World. New York: Doubleday & Company. p. 174.

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 54, 219. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Mayr, Ernst (1964). Systematics and the Origin of Species. New York: Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-0-486-21212-8.

- "AERC TAC's Taxonomic Recommendations" (PDF). www.aerc.be. AERC TAC. 1 December 2003. Retrieved 5 May 2008.

- Sangster, George J.; Collinson, Martin; Knox, Alan G.; Parkin, David T.; Svensson, Lars (2007). "Taxonomic recommendations for British birds: Fourth report". Ibis. 149 (4): 853–857. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2007.00758.x.

- Pierotti, R.J.; Good, T.P. (1994). Poole, A. (ed.). "Distinguishing Characteristics — Herring Gull — Birds of North America Online". The Birds of North America Online. doi:10.2173/bna.124. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- Olsen, Klaus Malling; Larsson, Hans (2004). Gulls: of North America, Europe, and Asia. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691119977.

- Harrison, Peter (1991). Seabirds: An Identification Guide. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-395-60291-1.

- Dunning, John B. Jr., ed. (1992). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- "Herring gull". All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- Spencer, S.; Omland, K. (2008). "Larus argentatus (On-line)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 12 June 2009.

- "Herring Gull Sounds, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 2020-04-02.

- Strong, R. M. (April 1914). "On the Habits and Behavior of the Herring Gull, Larus Argentatus Pont (Concluded)". The Auk. 31 (2): 178–199. doi:10.2307/4071717. JSTOR 4071717.

- Marcus, Adam (2006). "Feather Colors: What Birds See". Birder's World. p. 52. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- Copeland Bird Observatory. Annual Report for 2010

- "Birds of Conservation Concern" (PDF). British Trust for Ornithology. 2009.

- Bowey, K.; Newsome, M. (2012). The Birds of Durham. Durham Bird Club. ISBN 978-1-874701-03-3.

- Peterson, R.; Mountfort, G.; Hollom, P.A.D. (1967). A Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe (11th impression ed.). London: Collins.

- Pierotti, R.J.; Good, T.P. (1994). Poole, A. (ed.). "Behavior — Herring Gull — Birds of North America Online". The Birds of North America Online. doi:10.2173/bna.124. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- Pierotti, R.J.; Good, T.P. (1994). Poole, A. (ed.). "Food Habits — Herring Gull — Birds of North America Online". The Birds of North America Online. doi:10.2173/bna.124. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- Henry, Pierre-Yves; Aznar, Jean-Christophe (June 2006). "Tool-use in Charadrii: Active Bait-Fishing by a Herring Gull". Waterbirds. 29 (2): 233–234. doi:10.1675/1524-4695(2006)29[233:TICABB]2.0.CO;2.

- Tinbergen, N. (1960). The Herring Gull's World. New York: Basic Books, Inc. p. 297.

- Catania, Kenneth C.; Brosnan, Sarah Frances (22 October 2008). "Worm Grunting, Fiddling, and Charming—Humans Unknowingly Mimic a Predator to Harvest Bait". PLOS ONE. 3 (10): e3472. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3472C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003472. PMC 2566961. PMID 18852902.

- "National Audubon Society – Waterbirds – Herring Gull". audubon.org. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- "AnAge entry for Larus argentatus". The Animal Ageing and Longevity Database. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- "Guidance Note on applications for a licence to control gulls" (PDF). Natural England - Wildlife Management & Licensing. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-10-08. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- "Advice on how to deal with problem seagulls". Natural England – part of the U.K. government. 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- "General licence consultation follow up". Natural England – part of the U.K. government. 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-05-18. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- Fitch, Davey (28 May 2009). "Red alert for one fifth of UK's bird species!". The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- Rock, Peter (May 2003). "Birds of a feather flock together". Environmental Health Journal. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsbl.2019.0405

- "Lethal Bird Control (Culling)". Pigeon Control Advisory Service. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

Further reading

- Darwin, Charles (1979). The Illustrated Origin of Species. Abridged and Introduced by Richard Leakey. Faber and Faber. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-571-11477-1.

- Harris, Alan; Tucker, Laurel; Vinicombe, Keith (1994). The Macmillan Field Guide to Bird Identification. London: Macmillan.

- Snow, D.W.; Perrins, C.M. (1998). Birds of the Western Palearctic. Vol. 1 (Concise ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Larus argentatus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Larus argentatus. |

- Herring Gull videos from the BBC

- Map of Herring Gull distribution in summer and winter in Europe

- How Nature Works: Gull Territoriality – from Cornell Lab of Ornithology on YouTube

- Sound recordings of European herring gulls at BioAcoustica

- BirdLife species factsheet for Larus argentatus

- "Larus argentatus". Avibase.

- "Herring gull media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Herring gull photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Larus argentatus at IUCN Red List maps

- Herring gull – Larus argentatus – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Audio recordings of Europeanherring gull on Xeno-canto.

- Larus argentatus in Field Guide: Birds of the World on Flickr

- European herring gull media from ARKive