Grey seal

The grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) is found on both shores of the North Atlantic Ocean. It is a large seal of the family Phocidae, which are commonly referred to as "true seals" or "earless seals". It is the only species classified in the genus Halichoerus. Its name is spelled gray seal in the US; it is also known as Atlantic seal[2] and the horsehead seal.[2][3]

| Grey Seals | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male | |

.jpg.webp) | |

| Female with pup | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Clade: | Pinnipediformes |

| Clade: | Pinnipedia |

| Family: | Phocidae |

| Genus: | Halichoerus Nilsson, 1820 |

| Species: | H. grypus |

| Binomial name | |

| Halichoerus grypus (Fabricius, 1791) | |

| |

| Grey seal range.[1] | |

Taxonomy

There are two recognized subspecies of this seal:[4]

| Image | Subspecies | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Halichoerus grypus grypus Fabricius, 1791, earlier known as H. g. macrorhynchus and H. g. balticus | Baltic Sea |

| Halichoerus grypus atlantica Nehring, 1886 | western North Atlantic stock (eastern Canada and the northeastern United States), the eastern North Atlantic stock (British Isles, Iceland, Norway, Denmark, the Faroe Islands, and Russia)[5] |

The type specimen of H. g. grypus (specimen ZMUC M11-1525, caught off the island of Amager) was rediscovered in 2016, and a DNA test showed it belonged to a Baltic Sea specimen rather than from Greenland, as had previously been assumed. The name H. g. grypus was therefore transferred to the Baltic subspecies (replacing H. g. macrorhynchus), and the name H. g. atlantica resurrected for the Atlantic subspecies.[6]

Molecular studies have indicated that the eastern and western Atlantic populations have been genetically distinct for at least one million years, and could potentially be considered separate subspecies.[7]

Description

This is a fairly large seal, with bulls in the eastern Atlantic populations reaching 1.95–2.3 m (6 ft 5 in–7 ft 7 in) long and weighing 170–310 kg (370–680 lb); the cows are much smaller, typically 1.6–1.95 m (5 ft 3 in–6 ft 5 in) long and 100–190 kg (220–420 lb) in weight. Individuals from the western Atlantic are often much larger, with males averaging up to 2.7 m (8 ft 10 in) and reaching a weight of as much as 400 kg (880 lb) and females averaging up to 2.05 m (6 ft 9 in) and sometimes weighing up to 250 kg (550 lb). Record-sized bull grey seals can reach about 3.3 m (10 ft 10 in) in length.[8][9][10][11] A common average weight in Great Britain was found to be about 233 kg (514 lb) for males and 154.6 kg (341 lb) for females whereas in Nova Scotia, Canada adult males averaged 294.6 kg (649 lb) and adult females averaged 224.5 kg (495 lb).[9][12][13] It is distinguished from the smaller harbour seal by its straight head profile, nostrils set well apart, and fewer spots on its body.[14][15] Wintering hooded seals can be confused with grey seals as they are about the same size and somewhat share a large-nosed look but the hooded has a paler base colour and usually evidences a stronger spotting.[16] Grey seals lack external ear flaps and characteristically have large snouts.[17] Bull Greys have larger noses and a less curved profile than common seal bulls. Males are generally darker than females, with lighter patches and often scarring around the neck. Females are silver grey to brown with dark patches.

Ecology and distribution

In the United Kingdom and Ireland, the grey seal breeds in several colonies on and around the coasts. Notably large colonies are at Blakeney Point in Norfolk, Donna Nook in Lincolnshire, the Farne Islands off the Northumberland Coast (about 6,000 animals), Orkney and North Rona.[18] off the north coast of Scotland, Lambay Island off the coast of Dublin and Ramsey Island off the coast of Pembrokeshire. In the German Bight, colonies exist off the islands Sylt and Amrum and on Heligoland.[19]

In the Western North Atlantic, the grey seal is typically found in large numbers in the coastal waters of Canada and south to Nantucket in the United States. In Canada, it is typically seen in areas such as the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Newfoundland, the Maritimes, and Quebec. The largest colony in the world is at Sable Island, NS. In the United States it is found year-round off the coast of New England, in particular Maine and Massachusetts. Archaeological evidence confirms grey seals in southern New England with remains found on Block Island, Martha's Vineyard and near the mouth of the Quinnipiac River in New Haven, Connecticut.[20] Its natural range now extends much further south than previously recognised with confirmed sightings in North Carolina. Also, there is a report by Farley Mowat of historic breeding colonies as far south as Cape Hatteras, North Carolina.[3]

An isolated population exists in the Baltic Sea,[1] forming the H. grypus balticus subspecies.

Besides these very large colonies, many much smaller ones exist, some of which are well known as tourist attractions despite their small size. Such colonies include one on the Carrack rocks in Cornwall.

During the winter months grey seals can be seen hauled out on rocks, islands, and shoals not far from shore, occasionally coming ashore to rest. In the spring recently weaned pups and yearlings occasionally strand on beaches after becoming separated from their group.

Grey seals are vulnerable to typical predators for a pinniped mammal. Large sharks are known to prey on grey seals in Canada, particularly great white sharks but also, upon evidence, additionally Greenland sharks.[21][22] In the waters of Great Britain, grey seals are a fairly common prey species for killer whales.[23][24] Apparently, grey seal pups are sometimes taken alive by white-tailed eagles, as well.[1]

Diet

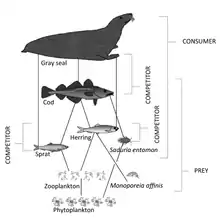

The grey seal feeds on a wide variety of fish, mostly benthic or demersal species, taken at depths down to 70 m (230 ft) or more. Sand eels (Ammodytes spp) are important in its diet in many localities. Cod and other gadids, flatfish, herring,[26] wrasse[27] and skates[28] are also important locally. However, it is clear that the grey seal will eat whatever is available, including octopus[29] and lobsters.[30] The average daily food requirement is estimated to be 5 kg (11 lb), though the seal does not feed every day and it fasts during the breeding season.

Recent observations and studies from Scotland, The Netherlands and Germany show that grey seals will also prey and feed on large animals like harbour seals and harbour porpoises.[31][32][33] In 2014, a male grey seal in the North Sea was documented and filmed killing and cannibalising 11 pups of its own species over the course of a week. Similar wounds on the carcasses of pups found elsewhere in the region suggest that cannibalism and infanticide may not be uncommon in grey seals. Male grey seals may engage in such behaviour potentially as a way of increasing reproductive success through access to easy prey without leaving prime territory.[34]

Communication

While it was originally understood that marine mammals communicate vocally, new research conducted by researchers at Monash University shows that grey seals clap their flippers as another form of communication. They clap their flippers underwater to deter a predator from attacking. If done during the mating season, the clapping can be used as a way to find a potential mate. The Monash researchers point out that seals are typically known for clapping, so this behavior may not be a surprise, but the clapping we know typically occurs in captivity. Clapping seals are associated with aquariums and zoos, but were never observed in the wild for this behavior. They were astonished at how loud these marine mammals were able to clap underwater, but it is logical for the reasons they do this.[35]

Reproduction

Grey seals are capital breeders; they forage to build up stored blubber, which is utilised when they are breeding and weaning their pups, as they do not forage for food at this time. They give birth to a single pup every year, with females' reproductive years beginning as early as 4 years old and extending up to 30 years of age. All parental care is provided by the female. During breeding, males don't provide parental care but they defend females against other males for mating.[36] The pups are born at around the mass of 14 kg.[37] They are born in autumn (September to December) in the eastern Atlantic and in winter (January to February) in the west, with a dense, soft silky white fur; at first small, they rapidly fatten up on their mothers' extremely fat-rich milk. The milk can consist of up to 60% fat.[37] Grey seal pups are precocial, with mothers returning to sea to forage once pups are weaned. Pups also undergo a post-weaning fast before leaving land and learning to swim.[38] Within a month or so they shed the pup fur, grow dense waterproof adult fur, and leave for the sea to learn to fish for themselves. In recent years, the number of grey seals has been on the rise in the west and in the U.S.[39] and Canada[40] there have been calls for a seal cull.

Seal pup first year survival rates are estimated to vary from 80-85%[41][42] to below 50%[43] depending on location and conditions. Starvation, due to difficulties in learning to feed, appears to be the main cause of pup death.[43]

Status

After near extirpation from hunting grey seals for oil, meat and skins in the United States, sightings began to increase in the late 1980s. Bounties were paid on all kinds of seals up until 1945 in Maine and 1962 in Massachusetts.[44] One year after Congress passed the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act preventing the harming or harassing of seals, a survey of the entire Maine coast found only 30 grey seals.[44] At first grey seal populations increased slowly but then rebounded from islands off Maine to Monomoy Island and Nantucket Island off of southern Cape Cod. The southernmost breeding colony was established on Muskeget Island with five pups born in 1988 and over 2,000 counted in 2008.[45] According to a genetics study, the United States population has formed as a result of recolonisation by Canadian seals.[45] By 2009, thousands of grey seals had taken up residence on or near popular swimming beaches on outer Cape Cod, resulting in sightings of great white sharks drawn close to shore to hunt the seals.[46] A count of 15,756 grey seals in southeastern Massachusetts coastal waters was made in 2011 by the National Marine Fisheries Service.[47] Grey seals are being seen increasingly in New York and New Jersey waters, and it is expected that they will establish colonies further south.

Human noise pollution continues to affect marine-life communication. This is typically important for marine mammals. It difficult to protect behaviors of mammals like the grey seal if we do not know all of their behaviors purposes. Since the recent discovery of their clapping communication, this is another factor to be aware of when looking at importance of reducing human noise.[35] Understanding species like this can ultimately help coming up with ways to protect them and allow them to thrive.

In the UK seals are protected under the Conservation of Seals Act 1970; however, it does not apply to Northern Ireland. In the UK there have also been calls for a cull from some fishermen claiming that stocks have declined due to the seals.

The population in the Baltic Sea has increased about 8% per year between 1990 and the mid 2000s, with the numbers becoming stagnant since 2005. As of 2011 hunting grey seals is legal in Sweden and Finland, with 50% of the quota being used. Other anthropogenic causes of death include drowning in fishing gear.[48]

Captivity

Grey seals have proved amenable to life in captivity and are commonly found zoo animals around their native range, particularly in Europe. Traditionally they were popular circus animals and often used in performances such as balancing and display acts. At least one grey seal, probably escaped from captivity, has been observed in the Black Sea near the coast of Ukraine.[49] Many seals in captivity are taught tricks such as clapping for human entertainment. While it was recently discovered that they clap in the wild as a means of communication, it can leave questions as to how this affects their overall communication as well.[50] They clap to ward off predators or to find mates, which are both vital components of life for the grey seal. By teaching them how to do this for entertainment purposes, the training of these tricks could be limiting their ability to effectively communicate these behaviors.

See also

References

- Bowen, D. (2016). "Halichoerus grypus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T9660A45226042. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T9660A45226042.en.

- Sokolov, Vladimir (1984). Пятиязычный словарь названий животных. Млекопитающие. Moscow.

- Mowat, Farley, Sea of Slaughter, Atlantic Monthly Press Publishing, First American Edition, 1984.

- Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- "Gray Seal". NOAA. 8 July 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- Olsen, Morten Tange; Galatius, Anders; Biard, Vincent; Gregersen, Kristian; Kinze, Carl Christian (April 2016). "The forgotten type specimen of the grey seal [Halichoerus grypus (Fabricius, 1791)] from the island of Amager, Denmark". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 178 (3): 713–720. doi:10.1111/zoj.12426.

- Boskovic, R.; et al. (1996). "Geographic distribution of mitochondrial DNA haplotypes in grey seals (Halichoerus grypus)". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 74 (10): 1787–1796. doi:10.1139/z96-199.

- Gray Seal (marine mammals) Archived 9 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine . what-when-how.com

- FAO Advisory Committee on Marine Resources Research (1982) Working Party on Marine Mammals; Mammals of the Sea, Volume 4. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

- Naughton, D. (2014). The Natural History of Canadian Mammals: Opossums and Carnivores. University of Toronto Press.

- Bjärvall, A., & Ullström, S. (1986). The mammals of Britain and Europe. London: Croom Helm.

- Lidgard, D. C., Boness, D. J., & Bowen, W. D. (2001). A novel mobile approach to investigating mating tactics in male grey seals (Halichoerus grypus). Journal of Zoology, 255(3), 313-320.

- Baker, S. R., Barrette, C., & Hammill, M. O. (1995). Mass transfer during lactation of an ice‐breeding pinniped, the grey seal (Halichoerus grypus), in Nova Scotia, Canada. Journal of Zoology, 236(4), 531-542.

- "How to identify British seals". BBC Wildlife. BBC. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- Middleton, Kevin. "Get the lowdown on seals". RSPB. Retrieved 23 October 2015.

- Perrin, W. F., Würsig, B., & Thewissen, J. G. M. (Eds.). (2009). Encyclopedia of marine mammals. Academic Press.

- Schuster, Marreno; Glen, Megan (2011). Marine Science: The Dynamic Ocean. US Satellite Laboratory: Pearson. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-13-317063-4.

- Stewart, J.E.; et al. (2014). "Finescale ecological niche modeling provides evidence that lactating grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) prefer access to fresh water in order to drink" (PDF). Marine Mammal Science. 30 (4): 1456–1472. doi:10.1111/mms.12126.

- Hahn, Melanie (13 January 2010). "Kegelrobben-Geburtenrekord auf Helgoland". Nordseewolf Magazin (in German). Archived from the original on 31 March 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- Waters, Joseph H. (February 1967). "Gray Seal Remains from Southern New England Archeological Sites". Journal of Mammalogy. 48 (1): 139–141. doi:10.2307/1378182. JSTOR 137818.

- Brodie, P., & Beck, B. (1983). Predation by sharks on the grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) in eastern Canada. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 40(3), 267-271.

- Lucas, Z. N., & Natanson, L. J. (2010). Two shark species involved in predation on seals at Sable Island, Nova Scotia, Canada. Proceedings of the Nova Scotian Institute of Science (NSIS), 45(2).

- Weir, C. R. (2002). Killer whales (Orcinus orca) in UK waters. British Wildlife, 14(2), 106-108.

- Bloc, D., & Lockyer, C. (1988). Killer whales (Orcinus area) in Faroese waters. Rit Fiskideildar.

- Karlson, A.M., Gorokhova, E., Gårdmark, A., Pekcan-Hekim, Z., Casini, M., Albertsson, J., Sundelin, B., Karlsson, O. and Bergström, L. (2020). "Linking consumer physiological status to food-web structure and prey food value in the Baltic Sea". Ambio, 49(2): 391–406. doi:10.1007/s13280-019-01201-1

- Stenman, Olavi (2007). "How does hunting grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) on Bothnian Bay spring ice influence the structure of seal and fish stocks?" (PDF). International Council for the Exploration of the Sea. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

Analysis of fish otolithes and other hard particles in the alimentary tract showed clearly that the herring (Clupea harengus) was the most important item of prey.

- Ridoux, Vincent; Spitz, J.; Vincent, Cecile; Walton, M. J. (2007). "Grey seal diet at the southern limit of its European distribution: combining dietary analyses and fatty acid profiles" (PDF). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 87 (1): 255–264. doi:10.1017/S002531540705463X. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- Savenkoff, Claude; Morissette, Lyne; Castonguay, Martin; Swain, Douglas P.; Hammill, Mike O.; Chabot, Denis; Hanson, J. Mark (2008). "Interactions between Marine Mammals and Fisheries: Implications for Cod Recovery". In Chen, Junying; Guo, Chuguang (eds.). Ecosystem Ecology Research Trends. Nova Science Publishers. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-60456-183-8.

- "Grey seal". Wales Nature & Outdoors. BBC Wales. 25 February 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- "The Grey Seal". Ask about Ireland. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- Leopold, Mardik F.; Begeman, Lineke; van Bleijswijk, Judith D. L.; IJsseldijk, Lonneke L.; Witte, Harry J.; Gröne, Andrea (2014). "Exposing the grey seal as a major predator of harbour porpoises". Proceedings of the Royal Society. 282 (1798): 20142429. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.2429. PMC 4262184. PMID 25429021.

- van Neer, Abbo; Jensen, Lasse F.; Siebert, Ursula (2015). "Grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) predation on harbour seals (Phoca vitulina) on the island of Helgoland, Germany". Journal of Sea Research. 97: 1–4. doi:10.1016/j.seares.2014.11.006.

- Hillmer, Angelika (16 February 2015). "Kegelrobben mit großem Appetit auf Schweinswale" [Grey seals with a great appetite for porpoises]. Hamburger Abendblatt (in German).

- First video footage of seal drowning and eating a pup. New Scientist (15 February 2016)

- https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2020/02/200203104510.htm

- Bubac, Christine M.; Coltman, David W.; Don Bowen, W.; Lidgard, Damian C.; Lang, Shelley L. C.; den Heyer, Cornelia E. (June 2018). "Repeatability and reproductive consequences of boldness in female gray seals". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 72 (6). doi:10.1007/s00265-018-2515-5. ISSN 0340-5443. S2CID 46975859.

- "Autumn spectacle: grey seal colonies". BBC Earth. 10 October 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- Bowen, William D.; Heyer, Cornelia E. den; McMillan, Jim I.; Iverson, Sara J. (1 April 2015). "Offspring size at weaning affects survival to recruitment and reproductive performance of primiparous gray seals". Ecology and Evolution. 5 (7): 1412–1424. doi:10.1002/ece3.1450. ISSN 2045-7758. PMC 4395171. PMID 25897381.

- Bidggod, Jess (16 August 2013) Thriving in Cape Cod’s Waters, Gray Seals Draw Fans and Foes. New York Times

- Plan to cull 70,000 grey seals gets Senate panel's approval – Newfoundland & Labrador – CBC News. Cbc.ca. 23 October 2012.

- Ailsa j, Hall; Bernie j, Mcconnell; Richard j, Barker (2008). "Factors affecting first-year survival in grey seals and their implications for life history strategy". Journal of Animal Ecology. 70: 138–149. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2001.00468.x.

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/229788805_Mortality_and_morbidity_in_Grey_seal_pups_Halichoerus_grypus_Studies_on_its_causes_effects_of_environment_the_nature_and_sources_of_infectious_agents_and_the_immunological_status_of_pups

- http://friendsofhorseyseals.co.uk/

- Barbara Lelli; David E. Harris & AbouEl-Makarim Aboueissa (2009). "Seal Bounties in Maine and Massachusetts, 1888 to 1962". Northeastern Naturalist. 16 (2): 239–254. doi:10.1656/045.016.0206. S2CID 85652019.

- Wood, S.A.; Frasier, T.R.; McLeod, B.A.; Gilbert, J.R.; White, B.N.; Bowen, W.D.; Hammill, M.O.; Waring, G.T.; Brault, S. (2011). "The genetics of recolonization: an analysis of the stock structure of grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) in the northwest Atlantic". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 89 (6): 490–497. doi:10.1139/z11-012.

- Once again, coastal waters getting seals’ approval Boston Globe. 3 October 2009.

- Gray Seal (Halichoerus grypus grypus): Western North Atlantic Stock (PDF) (Report). NMFS, NOAA. April 2014. pp. 342–350. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- Bäcklin, Britt-Marie; Moraeus, Charlotta; Kunnasranta, Mervi; Isomursu, Marja (2 September 2011). "Health Assessment in the Baltic grey seal (Halichoerus grypus)". HELCOM Indicator Fact Sheets 2011. HELCOM. Archived from the original on 3 November 2011.

- Marine Ecological Journal. Kovtun O.O. (2011) "Rare sightings and video-recording of the grey seal, Halichoerus grypus (Fabricius, 1791), in coastal grottoes of the eastern Crimea (Black Sea)". Archived 3 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine, 10(4):22. (in Russian)

- Hocking, David P.; Burville, Ben; Parker, William M. G.; Evans, Alistair R.; Park, Travis; Marx, Felix G. (2020). "Percussive underwater signaling in wild gray seals". Marine Mammal Science. 36 (2): 728–732. doi:10.1111/mms.12666.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Halichoerus grypus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Halichoerus grypus. |

- BBC Wales Nature: Grey Seal video clips

- Grey Seals on pinnipeds.org

- ARKive – images and movies of the grey seal from Atlantic (Halichoerus grypus)

- images of the grey seal from North Sea (Halichoerus grypus)

- Grey Seal Conservation Society (GSCS)

- The first filming of the grey seal in Eastern Crimea, Ukraine

- Photos of Grey seal on Sealife Collection