Owl

Owls are birds from the order Strigiformes /ˈstrɪdʒɪfɔːrmiːz/, which includes over 200 species of mostly solitary and nocturnal birds of prey typified by an upright stance, a large, broad head, binocular vision, binaural hearing, sharp talons, and feathers adapted for silent flight. Exceptions include the diurnal northern hawk-owl and the gregarious burrowing owl.

| Owl | |

|---|---|

%252C_Raigad%252C_Maharashtra.jpg.webp) | |

| Eastern barn owl (Tyto javanica stertens) Mangaon, Maharashtra, India | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Clade: | Afroaves |

| Order: | Strigiformes Wagler, 1830 |

| Families | |

|

Strigidae | |

| |

| Range of the owl, all species. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Strigidae sensu Sibley & Ahlquist | |

Owls hunt mostly small mammals, insects, and other birds, although a few species specialize in hunting fish. They are found in all regions of the Earth except the polar ice caps and some remote islands.

Owls are divided into two families: the true (or typical) owl family, Strigidae, and the barn-owl family, Tytonidae.

A group of owls is called a "parliament."[1]

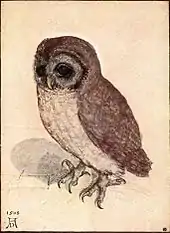

Anatomy

Owls possess large, forward-facing eyes and ear-holes, a hawk-like beak, a flat face, and usually a conspicuous circle of feathers, a facial disc, around each eye. The feathers making up this disc can be adjusted to sharply focus sounds from varying distances onto the owls' asymmetrically placed ear cavities. Most birds of prey have eyes on the sides of their heads, but the stereoscopic nature of the owl's forward-facing eyes permits the greater sense of depth perception necessary for low-light hunting. Although owls have binocular vision, their large eyes are fixed in their sockets—as are those of most other birds—so they must turn their entire heads to change views. As owls are farsighted, they are unable to clearly see anything within a few centimeters of their eyes. Caught prey can be felt by owls with the use of filoplumes—hairlike feathers on the beak and feet that act as "feelers". Their far vision, particularly in low light, is exceptionally good.

Owls can rotate their heads and necks as much as 270°. Owls have 14 neck vertebrae compared to seven in humans, which makes their necks more flexible. They also have adaptations to their circulatory systems, permitting rotation without cutting off blood to the brain: the foramina in their vertebrae through which the vertebral arteries pass are about 10 times the diameter of the artery, instead of about the same size as the artery as in humans; the vertebral arteries enter the cervical vertebrae higher than in other birds, giving the vessels some slack, and the carotid arteries unite in a very large anastomosis or junction, the largest of any bird's, preventing blood supply from being cut off while they rotate their necks. Other anastomoses between the carotid and vertebral arteries support this effect.[2][3]

The smallest owl—weighing as little as 31 g (1 3⁄32 oz) and measuring some 13.5 cm (5 1⁄4 in)—is the elf owl (Micrathene whitneyi).[4] Around the same diminutive length, although slightly heavier, are the lesser known long-whiskered owlet (Xenoglaux loweryi) and Tamaulipas pygmy owl (Glaucidium sanchezi).[4] The largest owls are two similarly sized eagle owls; the Eurasian eagle-owl (Bubo bubo) and Blakiston's fish owl (Bubo blakistoni). The largest females of these species are 71 cm (28 in) long, have a 190 cm (75 in) wing span, and weigh 4.2 kg (9 1⁄4 lb).[4][5][6][7][8]

Different species of owls produce different sounds; this distribution of calls aids owls in finding mates or announcing their presence to potential competitors, and also aids ornithologists and birders in locating these birds and distinguishing species. As noted above, their facial discs help owls to funnel the sound of prey to their ears. In many species, these discs are placed asymmetrically, for better directional location.

Owl plumage is generally cryptic, although several species have facial and head markings, including face masks, ear tufts, and brightly colored irises. These markings are generally more common in species inhabiting open habitats, and are thought to be used in signaling with other owls in low-light conditions.[9]

Sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is a physical difference between males and females of a species. Females owls are typically larger than the males.[10] The degree of size dimorphism varies across multiple populations and species, and is measured through various traits, such as wing span and body mass.[10] Overall, female owls tend to be slightly larger than males. The exact explanation for this development in owls is unknown. However, several theories explain the development of sexual dimorphism in owls.

One theory suggests that selection has led males to be smaller because it allows them to be efficient foragers. The ability to obtain more food is advantageous during breeding season. In some species, female owls stay at their nest with their eggs while it is the responsibility of the male to bring back food to the nest.[11] However, if food is scarce, the male first feeds himself before feeding the female.[12] Small birds, which are agile, are an important source of food for owls. Male burrowing owls have been observed to have longer wing chords than females, despite being smaller than females.[12] Furthermore, owls have been observed to be roughly the same size as their prey.[12] This has also been observed in other predatory birds,[11] which suggests that owls with smaller bodies and long wing chords have been selected for because of the increased agility and speed that allows them to catch their prey.

Another popular theory suggests that females have not been selected to be smaller like male owls because of their sexual roles. In many species, female owls may not leave the nest. Therefore, females may have a larger mass to allow them to go for a longer period of time without starving. For example, one hypothesized sexual role is that larger females are more capable of dismembering prey and feeding it to their young, hence female owls are larger than their male counterparts.[10]

A different theory suggests that the size difference between male and females is due to sexual selection: since large females can choose their mate and may violently reject a male's sexual advances, smaller male owls that have the ability to escape unreceptive females are more likely to have been selected.[12]

If the character is stable, there can be different optimums for both sexes. Selection operates on both sexes at the same time; therefore it is necessary to explain not only why one of the sexes is relatively bigger, but also why the other sex is smaller.[13] If owls are still evolving towards smaller bodies and longer wing chords, according to V. Geodakyan's Evolutionary Theory of Sex, males should be more advanced on these characters. Males are viewed as an evolutionary vanguard of a population, and sexual dimorphism on the character, as an evolutionary “distance” between the sexes. “Phylogenetic rule of sexual dimorphism” states that if there exists a sexual dimorphism on any character, then the evolution of this trait goes from the female form towards the male one.[14]

Adaptations for hunting

All owls are carnivorous birds of prey and live mainly on a diet of insects and small rodents such as mice, rats, and hares. Some owls are also specifically adapted to hunt fish. They are very adept in hunting in their respective environments. Since owls can be found in nearly all parts of the world and across a multitude of ecosystems, their hunting skills and characteristics vary slightly from species to species, though most characteristics are shared among all species.

Flight and feathers

Most owls share an innate ability to fly almost silently and also more slowly in comparison to other birds of prey. Most owls live a mainly nocturnal lifestyle and being able to fly without making any noise gives them a strong advantage over their prey that are listening for the slightest sound in the night. A silent, slow flight is not as necessary for diurnal and crepuscular owls given that prey can usually see an owl approaching. Owls’ feathers are generally larger than the average birds’ feathers, have fewer radiates, longer pennulum, and achieve smooth edges with different rachis structures.[15] Serrated edges along the owl's remiges bring the flapping of the wing down to a nearly silent mechanism. The serrations are more likely reducing aerodynamic disturbances, rather than simply reducing noise.[16] The surface of the flight feathers is covered with a velvety structure that absorbs the sound of the wing moving. These unique structures reduce noise frequencies above 2 kHz,[17] making the sound level emitted drop below the typical hearing spectrum of the owl's usual prey[17][18] and also within the owl's own best hearing range.[19][20] This optimizes the owl's ability to silently fly to capture prey without the prey hearing the owl first as it flies in. It also allows the owl to monitor the sound output from its flight pattern.

The feather adaption that allows silent flight means that barn owl feathers are not waterproof. To retain the softness and silent flight, the barn owl cannot use the preen oil or powder dust that other species use for waterproofing. In wet weather, they cannot hunt and this may be disastrous during the breeding season. Barn owls are frequently found drowned in livestock drinking troughs, since they land to drink and bathe, but are unable to climb out. Owls can struggle to keep warm, because of their lack of waterproofing, so large numbers of downy feathers help them to retain body heat.[21]

Vision

Eyesight is a particular characteristic of the owl that aids in nocturnal prey capture. Owls are part of a small group of birds that live nocturnally, but do not use echolocation to guide them in flight in low-light situations. Owls are known for their disproportionally large eyes in comparison to their skulls. An apparent consequence of the evolution of an absolutely large eye in a relatively small skull is that the eye of the owl has become tubular in shape. This shape is found in other so-called nocturnal eyes, such as the eyes of strepsirrhine primates and bathypelagic fishes.[22] Since the eyes are fixed into these sclerotic tubes, they are unable to move the eyes in any direction.[23] Instead of moving their eyes, owls swivel their heads to view their surroundings. Owls' heads are capable of swiveling through an angle of roughly 270°, easily enabling them to see behind them without relocating the torso.[23] This ability keeps bodily movement at a minimum, thus reduces the amount of sound the owl makes as it waits for its prey. Owls are regarded as having the most frontally placed eyes among all avian groups, which gives them some of the largest binocular fields of vision. However, owls are farsighted and cannot focus on objects within a few centimeters of their eyes.[22][24] These mechanisms are only able to function due to the large-sized retinal image.[25] Thus, the primary nocturnal function in the vision of the owl is due to its large posterior nodal distance; retinal image brightness is only maximized to the owl within secondary neural functions.[25] These attributes of the owl cause its nocturnal eyesight to be far superior to that of its average prey.[25]

Hearing

Owls exhibit specialized hearing functions and ear shapes that also aid in hunting. They are noted for asymmetrical ear placements on the skull in some genera. Owls can have either internal or external ears, both of which are asymmetrical. Asymmetry has not been reported to extend to the middle or internal ear of the owl. Asymmetrical ear placement on the skull allows the owl to pinpoint the location of its prey. This is especially true for strictly nocturnal species such as the barn owls Tyto or Tengmalm's owl.[23] With ears set at different places on its skull, an owl is able to determine the direction from which the sound is coming by the minute difference in time that it takes for the sound waves to penetrate the left and right ears. The owl turns its head until the sound reaches both ears at the same time, at which point it is directly facing the source of the sound. This time difference between ears is about 30 microseconds. Behind the ear openings are modified, dense feathers, densely packed to form a facial ruff, which creates an anterior-facing, concave wall that cups the sound into the ear structure.[26] This facial ruff is poorly defined in some species, and prominent, nearly encircling the face, in other species. The facial disk also acts to direct sound into the ears, and a downward-facing, sharply triangular beak minimizes sound reflection away from the face. The shape of the facial disk is adjustable at will to focus sounds more effectively.[23]

The prominences above a great horned owl's head are commonly mistaken as its ears. This is not the case; they are merely feather tufts. The ears are on the sides of the head in the usual location (in two different locations as described above).

Talons

While the auditory and visual capabilities of the owl allow it to locate and pursue its prey, the talons and beak of the owl do the final work. The owl kills its prey using these talons to crush the skull and knead the body.[23] The crushing power of an owl's talons varies according to prey size and type, and by the size of the owl. The burrowing owl (Athene cunicularia), a small, partly insectivorous owl, has a release force of only 5 N. The larger barn owl (Tyto alba) needs a force of 30 N to release its prey, and one of the largest owls, the great horned owl (Bubo virginianus) needs a force over 130 N to release prey in its talons.[27] An owl's talons, like those of most birds of prey, can seem massive in comparison to the body size outside of flight. The Tasmanian masked owl has some of the proportionally longest talons of any bird of prey; they appear enormous in comparison to the body when fully extended to grasp prey.[28] An owl's claws are sharp and curved. The family Tytonidae has inner and central toes of about equal length, while the family Strigidae has an inner toe that is distinctly shorter than the central one.[27] These different morphologies allow efficiency in capturing prey specific to the different environments they inhabit.

Beak

The beak of the owl is short, curved, and downward-facing, and typically hooked at the tip for gripping and tearing its prey. Once prey is captured, the scissor motion of the top and lower bill is used to tear the tissue and kill. The sharp lower edge of the upper bill works in coordination with the sharp upper edge of the lower bill to deliver this motion. The downward-facing beak allows the owl's field of vision to be clear, as well as directing sound into the ears without deflecting sound waves away from the face.

Camouflage

The coloration of the owl's plumage plays a key role in its ability to sit still and blend into the environment, making it nearly invisible to prey. Owls tend to mimic the coloration and sometimes the texture patterns of their surroundings, the barn owl being an exception. The snowy owl (Bubo scandiacus) appears nearly bleach-white in color with a few flecks of black, mimicking their snowy surroundings perfectly, while the speckled brown plumage of the tawny owl (Strix aluco) allows it to lie in wait among the deciduous woodland it prefers for its habitat. Likewise, the mottled wood-owl (Strix ocellata) displays shades of brown, tan and black, making the owl nearly invisible in the surrounding trees, especially from behind. Usually, the only tell-tale sign of a perched owl is its vocalizations or its vividly colored eyes.

Behavior

Most owls are nocturnal, actively hunting their prey in darkness. Several types of owls, however, are crepuscular—active during the twilight hours of dawn and dusk; one example is the pygmy owl (Glaucidium). A few owls are active during the day, also; examples are the burrowing owl (Speotyto cunicularia) and the short-eared owl (Asio flammeus).

Much of the owls' hunting strategy depends on stealth and surprise. Owls have at least two adaptations that aid them in achieving stealth. First, the dull coloration of their feathers can render them almost invisible under certain conditions. Secondly, serrated edges on the leading edge of owls' remiges muffle an owl's wing beats, allowing an owl's flight to be practically silent. Some fish-eating owls, for which silence has no evolutionary advantage, lack this adaptation.

An owl's sharp beak and powerful talons allow it to kill its prey before swallowing it whole (if it is not too big). Scientists studying the diets of owls are helped by their habit of regurgitating the indigestible parts of their prey (such as bones, scales, and fur) in the form of pellets. These "owl pellets" are plentiful and easy to interpret, and are often sold by companies to schools for dissection by students as a lesson in biology and ecology.[29]

Breeding and reproduction

Owl eggs typically have a white color and an almost spherical shape, and range in number from a few to a dozen, depending on species and the particular season; for most, three or four is the more common number. In at least one species, female owls do not mate with the same male for a lifetime. Female burrowing owls commonly travel and find other mates, while the male stays in his territory and mates with other females.[30]

Evolution and systematics

The systematic placement of owls is disputed. For example, the Sibley–Ahlquist taxonomy of birds finds that, based on DNA-DNA hybridization, owls are more closely related to the nightjars and their allies (Caprimulgiformes) than to the diurnal predators in the order Falconiformes; consequently, the Caprimulgiformes are placed in the Strigiformes, and the owls in general become a family, the Strigidae. A recent study indicates that the drastic rearrangement of the genome of the accipitrids may have obscured any close relationship of theirs with groups such as the owls.[31] In any case, the relationships of the Caprimulgiformes, the owls, the falcons, and the accipitrid raptors are not resolved to satisfaction; currently, a trend to consider each group (with the possible exception of the accipitrids) as a distinct order is increasing.

Some 220 to 225 extant species of owls are known, subdivided into two families: 1. true owls or typical owls family (Strigidae) and 2. barn-owls family (Tytonidae). Some entirely extinct families have also been erected based on fossil remains; these differ much from modern owls in being less specialized or specialized in a very different way (such as the terrestrial Sophiornithidae). The Paleocene genera Berruornis and Ogygoptynx show that owls were already present as a distinct lineage some 60–57 million years ago (Mya), hence, possibly also some 5 million years earlier, at the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs. This makes them one of the oldest known groups of non-Galloanserae landbirds. The supposed "Cretaceous owls" Bradycneme and Heptasteornis are apparently non-avialan maniraptors.[32]

During the Paleogene, the Strigiformes radiated into ecological niches now mostly filled by other groups of birds. The owls as known today, though, evolved their characteristic morphology and adaptations during that time, too. By the early Neogene, the other lineages had been displaced by other bird orders, leaving only barn-owls and typical owls. The latter at that time were usually a fairly generic type of (probably earless) owls similar to today's North American spotted owl or the European tawny owl; the diversity in size and ecology found in typical owls today developed only subsequently.

Around the Paleogene-Neogene boundary (some 25 Mya), barn-owls were the dominant group of owls in southern Europe and adjacent Asia at least; the distribution of fossil and present-day owl lineages indicates that their decline is contemporary with the evolution of the different major lineages of true owls, which for the most part seems to have taken place in Eurasia. In the Americas, rather, an expansion of immigrant lineages of ancestral typical owls occurred.

The supposed fossil herons "Ardea" perplexa (Middle Miocene of Sansan, France) and "Ardea" lignitum (Late Pliocene of Germany) were more probably owls; the latter was apparently close to the modern genus Bubo. Judging from this, the Late Miocene remains from France described as "Ardea" aureliensis should also be restudied.[33] The Messelasturidae, some of which were initially believed to be basal Strigiformes, are now generally accepted to be diurnal birds of prey showing some convergent evolution towards owls. The taxa often united under Strigogyps[34] were formerly placed in part with the owls, specifically the Sophiornithidae; they appear to be Ameghinornithidae instead.[35][36][37]

For fossil species and paleosubspecies of extant taxa, see the genus and species articles. For a full list of extant and recently extinct owls, see the article List of owl species.

Unresolved and basal forms (all fossil)

- Berruornis (Late Paleocene of France) basal? Sophornithidae?

- Strigiformes gen. et ap. indet. (Late Paleocene of Zhylga, Kazakhstan)

- Palaeoglaux (Middle – Late Eocene of West-Central Europe) own family Palaeoglaucidae or Strigidae?

- Palaeobyas (Late Eocene/Early Oligocene of Quercy, France) Tytonidae? Sophiornithidae?

- Palaeotyto (Late Eocene/Early Oligocene of Quercy, France) Tytonidae? Sophiornithidae?

- Strigiformes gen. et spp. indet. (Early Oligocene of Wyoming, U.S.)[33]

Ogygoptyngidae

- Ogygoptynx (Middle/Late Paleocene of Colorado, U.S.)

Protostrigidae

- Eostrix (Early Eocene of United States, Europe, and Mongolia). E. gulottai is the smallest known fossil (or living) owl.[38]

- Minerva (Middle – Late Eocene of western U.S.) formerly Protostrix, includes "Aquila" ferox, "Aquila" lydekkeri, and "Bubo" leptosteus

- Oligostrix (mid-Oligocene of Saxony, Germany)

Sophiornithidae

- Sophiornis

The family Tytonidae: barn owls

- Genus Tyto – the barn owls, grass owls and masked owls, stand up to 500 mm (20 in) tall; some 15 extant species and possibly one recently extinct

- Genus Phodilus – the bay owls, two to three extant species and possibly one recently extinct

Fossil genera

- Nocturnavis (Late Eocene/Early Oligocene) includes "Bubo" incertus

- Selenornis (Late Eocene/Early Oligocene) – includes "Asio" henrici

- Necrobyas (Late Eocene/Early Oligocene – Late Miocene) includes "Bubo" arvernensis and Paratyto

- Prosybris (Early Oligocene? – Early Miocene)

Placement unresolved

- Tytonidae gen. et sp. indet. "TMT 164" (Middle Miocene) – Prosybris?

The family Strigidae: true owls or typical owls

- Genus Aegolius – the saw-whet owls, four species

- Genus Asio – the eared owls, eight species

- Genus Athene – two to four species (depending on whether the genera Speotyto and Heteroglaux are included or not)

- Genus Bubo – the horned owls, eagle-owls and fish-owls; paraphyletic with the genera Nyctea, Ketupa, and Scotopelia, some 25 species

- Genus Ciccaba – four species; these have been transferred to Strix

- Genus Glaucidium – the pygmy owls, about 30–35 species

- Genus Gymnasio – the Puerto Rican owl

- Genus Gymnoglaux – the bare-legged owl or Cuban screech-owl

- Genus Lophostrix – the crested owl

- Genus Jubula – the maned owl

- Genus Megascops – the screech owls, some 20 species

- Genus Micrathene – the elf owl

- Genus Ninox – the Australasian hawk-owls or boobooks, some 20 species

- Genus Otus – the scops owls; probably paraphyletic, about 45 species

- Genus Pseudoscops – the Jamaican owl

- Genus Psiloscops – the flammulated owl

- Genus Ptilopsis – the white-faced owls, two species

- Genus Pulsatrix – the spectacled owls, three species

- Genus Strix – the earless owls, about 15 species, including four previously assigned to Ciccaba

- Genus Surnia – the northern hawk-owl

- Genus Taenioptynx

- Genus Uroglaux – the Papuan hawk-owl

- Genus Xenoglaux – the long-whiskered owlet

Extinct genera

- Genus Grallistrix – the stilt-owls, four species; prehistoric

- Genus Ornimegalonyx – the Caribbean giant owls, one to two species; prehistoric

Fossil genera

- Mioglaux (Late Oligocene? – Early Miocene of West-Central Europe) – includes "Bubo" poirreiri

- Intutula (Early/Middle – ?Late Miocene of Central Europe) – includes "Strix/Ninox" brevis

- Alasio (Middle Miocene of Vieux-Collonges, France) – includes "Strix" collongensis

- Oraristrix – the Brea owl (Late Pleistocene)

Placement unresolved

- "Otus/Strix" wintershofensis: fossil (Early/Middle Miocene of Wintershof West, Germany) – may be close to extant genus Ninox[33]

- "Strix" edwardsi – fossil (Middle/Late? Miocene)

- "Asio" pygmaeus – fossil (Early Pliocene of Odessa, Ukraine)

- Strigidae gen. et sp. indet. UMMP V31030 (Late Pliocene) – Strix/Bubo?

- the Ibizan owl, Strigidae gen. et sp. indet. – prehistoric[39]

Symbolism and mythology

African cultures

Among the Kikuyu of Kenya, it was believed that owls were harbingers of death. If one saw an owl or heard its hoot, someone was going to die. In general, owls are viewed as harbingers of bad luck, ill health, or death. The belief is widespread even today.[40]

Asia

In Mongolia, the owl is regarded as a benign omen. In one story, Genghis Khan was hiding from enemies in a small coppice when an owl roosted in the tree above him, which caused his pursuers to think no man could be hidden there.[41]

In modern Japan, owls are regarded as lucky and are carried in the form of a talisman or charm.[42]

Ancient European and modern Western culture

The modern West generally associates owls with wisdom and vigilance. This link goes back at least as far as Ancient Greece, where Athens, noted for art and scholarship, and Athena, Athens' patron goddess and the goddess of wisdom, had the owl as a symbol.[43] Marija Gimbutas traces veneration of the owl as a goddess, among other birds, to the culture of Old Europe, long pre-dating Indo-European cultures.[44]

T. F. Thiselton-Dyer, in his 1883 Folk-lore of Shakespeare, says that "from the earliest period it has been considered a bird of ill-omen," and Pliny tells us how, on one occasion, even Rome itself underwent a lustration, because one of them strayed into the Capitol. He represents it also as a funereal bird, a monster of the night, the very abomination of human kind. Virgil describes its death-howl from the top of the temple by night, a circumstance introduced as a precursor of Dido's death. Ovid, too, constantly speaks of this bird's presence as an evil omen; and indeed the same notions respecting it may be found among the writings of most of the ancient poets."[45] A list of "omens drear" in John Keats' Hyperion includes the "gloom-bird's hated screech."[46] Pliny the Elder reports that owl's eggs were commonly used as a hangover cure.[47]

Hinduism

In Hinduism, an owl is the vahana (mount) of the goddess Lakshmi.[48]

Native American cultures

People often allude to the reputation of owls as bearers of supernatural danger when they tell misbehaving children, "the owls will get you",[49] and in most Native American folklore, owls are a symbol of death. For example:

- According to the Apache and Seminole tribes, hearing owls hooting is considered the subject of numerous "bogeyman" stories told to warn children to remain indoors at night or not to cry too much, otherwise the owl may carry them away.[50][51] In some tribal legends, owls are associated with spirits of the dead, and the bony circles around an owl's eyes are said to comprise the fingernails of apparitional humans. Sometimes owls are said to carry messages from beyond the grave or deliver supernatural warnings to people who have broken tribal taboos.[52]

- The Aztecs and the Maya, along with other natives of Mesoamerica, considered the owl a symbol of death and destruction. In fact, the Aztec god of death, Mictlantecuhtli, was often depicted with owls.[53] There is an old saying in Mexico that is still in use:[54] Cuando el tecolote canta, el indio muere ("When the owl cries/sings, the Indian dies"). The Popol Vuh, a Mayan religious text, describes owls as messengers of Xibalba (the Mayan "Place of Fright").[55]

- The belief that owls are messengers and harbingers of the dark powers is also found among the Hočągara (Winnebago) of Wisconsin.[56] When in earlier days the Hočągara committed the sin of killing enemies while they were within the sanctuary of the chief's lodge, an owl appeared and spoke to them in the voice of a human, saying, "From now on, the Hočągara will have no luck." This marked the beginning of the decline of their tribe.[57] An owl appeared to Glory of the Morning, the only female chief of the Hočąk nation, and uttered her name. Soon afterwards, she died.[58][59]

- According to the culture of the Hopi, a Uto-Aztec tribe, taboos surround owls, which are associated with sorcery and other evils.

- The Ojibwe tribes, as well as their Aboriginal Canadian counterparts, used an owl as a symbol for both evil and death. In addition, they used owls as a symbol of very high status of spiritual leaders of their spirituality.[60]

- The Pawnee tribes viewed owls as the symbol of protection from any danger within their realms.[60]

- The Puebloan peoples associated owls with Skeleton Man, the god of death and the spirit of fertility.[60]

- The Yakama tribes use an owl as a powerful totem, often to guide where and how forests and natural resources are useful with management.[60]

Rodent control

Encouraging natural predators to control rodent population is a natural form of pest control, along with excluding food sources for rodents. Placing a nest box for owls on a property can help control rodent populations (one family of hungry barn owls can consume more than 3,000 rodents in a nesting season) while maintaining the naturally balanced food chain.[61]

Attacks on humans

Although humans and owls frequently live together in harmony, there have been incidents when owls have attacked humans. For example, in January 2013, a man from Inverness, Scotland suffered heavy bleeding and went into shock after being attacked by an owl, which was likely a 50-centimetre-tall (20 in) eagle-owl.[62] The photographer Eric Hosking lost his left eye after attempting to photograph a tawny owl, which inspired the title of his 1970 autobiography, An Eye for a Bird.

Conservation issues

_Male.jpg.webp)

All owls are listed in Appendix II of the international CITES treaty (the Convention on Illegal Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora). Although owls have long been hunted, a 2008 news story from Malaysia indicates that the magnitude of owl poaching may be on the rise. In November 2008, TRAFFIC reported the seizure of 900 plucked and "oven-ready" owls in Peninsular Malaysia. Said Chris Shepherd, Senior Programme Officer for TRAFFIC's Southeast Asia office, "This is the first time we know of where 'ready-prepared' owls have been seized in Malaysia, and it may mark the start of a new trend in wild meat from the region. We will be monitoring developments closely." TRAFFIC commended the Department of Wildlife and National Parks in Malaysia for the raid that exposed the huge haul of owls. Included in the seizure were dead and plucked barn owls, spotted wood owls, crested serpent eagles, barred eagles, and brown wood owls, as well as 7,000 live lizards.[65]

References

- Lipton, James (1991). An Exaltation of Larks. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-30044-0.

- "International Science & Engineering Visualization Challenge: Posters & Graphics". Science. 339 (6119): 514–515. 1 February 2013. doi:10.1126/science.339.6119.514.

- "Owl mystery unraveled: Scientists explain how bird can rotate its head without cutting off blood supply to brain". Johns Hopkins Medicine. 31 January 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- Konig, Claus; Welck, Friedhelm and Jan-Hendrik Becking (1999) Owls: A Guide to the Owls of the World, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-07920-3.

- Eurasian Eagle Owl. Oiseaux-birds.com. Retrieved 2013-03-02.

- Eurasian Eagle Owl – Bubo bubo – Information, Pictures, Sounds. Owlpages.com (13 August 2012). Retrieved 2013-03-02.

- Take A Peek At Boo, The Eagle Owl – The Quillcards Blog. Quillcards.com (23 September 2009). Retrieved 2013-03-02.

- Blakiston's Fish Owl Project. Fishowls.com (26 February 2013). Retrieved 2013-03-02.

- Galeotti, Paolo; Diego Rubolini (November 2007). "Head ornaments in owls: what are their functions?". Journal of Avian Biology. 38 (6): 731–736. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2007.04143.x.

- Lundberg, Arne (May 1986). "Adaptive advantages of reversed sexual size dimorphism in European owls". Ornis Scandinavica. 17 (2): 133–140. doi:10.2307/3676862. JSTOR 3676862.

- Krüger, Oliver (September 2005). "The evolution of reversed sexual size dimorphism in hawks, falcons and owls: a comparative study" (PDF). Evolutionary Ecology. 19 (5): 467–486. doi:10.1007/s10682-005-0293-9. S2CID 22181702.

- Mueller, H.C. (1986). "The evolution of reversed sexual dimorphism in owls: an empirical analysis of possible selective factors" (PDF). The Wilson Bulletin. 19 (5): 467. doi:10.1007/s10682-005-0293-9. S2CID 22181702.

- Székely T, Freckleton R. P., Reynolds J. D. (2004) Sexual selection explains Rensch's rule of size dimorphism in shorebirds. PNAS, 101, N. 33, p. 12224-12227.

- Geodakyan V. A. (1985) Sexual dimorphism. In: Evolution and morphogenesis. (Mlikovsky J., Novak V. J. A., eds.), Academia, Praha, p. 467–477.

- Bachmann T.; Klän S.; Baughmgartner W.; Klaas M.; Schröder W. & Wagner H. (2007). "Morphometric characterisation of wing feathers of the barn owl Tyto alba pratincola and the pigeon Columba livia". Frontiers in Zoology. 4: 23. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-4-23. PMC 2211483. PMID 18031576.

- Stevenson, John (18 November 2020). "Small finlets on owl feathers point the way to less aircraft noise". Phys.org. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- Neuhaus W.; Bretting H. & Schweizer B. (1973). "Morphologische und funktionelle Untersuchungen über den, lautlosen" Flug der Eulen (strix aluco) im Vergleich zum Flug der Enten (Anas platyrhynchos)". Biologisches Zentralblatt. 92: 495–512.

- Willott J.F. (2001) Handbook of Mouse Auditory Research CRC Press ISBN 1420038737.

- Dyson, M. L.; Klump, G. M.; Gauger, B. (April 1998). "Absolute hearing thresholds and critical masking ratios in the European barn owl: a comparison with other owls". Journal of Comparative Physiology. 182 (5): 695–702. doi:10.1007/s003590050214. S2CID 24641904.

- Webster, Douglas B.; Fay, Richard R. (6 December 2012). "Hearing in Birds". The Evolutionary Biology of Hearing. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 547. ISBN 978-1-4612-2784-7.

- Ian Hayward (27 July 2007). "Ask an expert: Are barn owl feathers waterproof?". RSPB. Retrieved 29 December 2015.

- Walls G.L. (1942) The vertebrate eye and its adaptive radiation, Cranbook Institute of Science.

- König, Claus, Friedhelm Weick & Jan-Hendrik Becking (1999). Owls: A guide to the owls of the world. Yale Univ Press, 1999. ISBN 0300079206

- Hughes A. (1979). "A schematic eye for the rat". Vision Res. 19 (5): 569–588. doi:10.1016/0042-6989(79)90143-3. PMID 483586. S2CID 10317667.

- Martin G.R. (1982). "An owl's eye: schematic optics and visual performance in Strix aluco L". J Comp Physiol. 145 (3): 341–349. doi:10.1007/BF00619338. S2CID 35039625.

- Norberg, R.A. (31 August 1977). "Occurrence and independent evolution of bilateral ear asymmetry in owls and implications on owl taxonomy". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 280 (973): 375–408. Bibcode:1977RSPTB.280..375N. doi:10.1098/rstb.1977.0116.

- Marti, C. D. (1974). "Feeding Ecology of Four Sympatric Owls" (PDF). The Condor. 76 (1): 45–61. doi:10.2307/1365983. JSTOR 1365983.

- Einoder, Luke D. & Alastair M. M. Richardson (2007). "Aspects of the Hindlimb Morphology of Some Australian Birds of Prey: A Comparative and Quantitative Study". The Auk. 124 (3): 773–788. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2007)124[773:AOTHMO]2.0.CO;2.

- Owl Pellets in the Classroom: Safety Guidelines. carolina.com

- Martin, Dennis J. (1973). "Selected Aspects of Burrowing Owl Ecology and Behavior". The Condor. 75 (4): 446–456. doi:10.2307/1366565. JSTOR 1366565. S2CID 55069283.

- Haaramo, Mikko (2006): Mikko's Phylogeny Archive: "Caprimulgiformes" – Nightjars. Version of 11 May 2006. Retrieved 2007-11-08. In reality, the presumed distant relationship of the accipitrids—namely, the "Accipitriformes" according to Sibley and Ahlquist (1990)—with owls (and most other bird lineages) is most likely due to systematic error. Accipitrids have undergone drastic chromosome rearrangement and thus appear in DNA-DNA hybridization generally unlike other living birds.

- Mortimer, Michael (2004): The Theropod Database: Phylogeny of taxa Archived 16 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2013-03-02.

- Olson, Storrs L. (1985): The fossil record of birds. In: Farner, D.S.; King, J.R. & Parkes, Kenneth C. (eds.): Avian Biology 8: 79–238 (131, 267). Academic Press, New York.

- Mayr, Gerald (2005). ""Old World phorusrhacids" (Aves, Phorusrhacidae): a new look at Strigogyps ("Aenigmavis") sapea (Peters 1987)". PaleoBios (Berkeley). 25 (1): 11–16.

- Alvarenga, Herculano M. F. & Höfling, Elizabeth (2003). "Systematic revision of the Phorusrhacidae (Aves: Ralliformes)". Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia. 43 (4): 55–91. doi:10.1590/S0031-10492003000400001.

- Larco Herrera, Rafael and Berrin, Kathleen (1997) The Spirit of Ancient Peru Thames and Hudson, New York, ISBN 0500018022.

- Peters, Dieter Stefan (January 2007). "The fossil family Ameghinornithidae (Mourer-Chauviré 1981): a short synopsis" (PDF). Journal of Ornithology. 148 (1): 25–28. doi:10.1007/s10336-006-0095-z. S2CID 27322057.

- Sánchez Marco, Antonio (2004). "Avian zoogeographical patterns during the Quaternary in the Mediterranean region and paleoclimatic interpretation" (PDF). Ardeola. 51 (1): 91–132.

- "Owls in Lore and Culture – The Owl Pages". Owlpages.com.

- Sparks & Soper (1979). Owls: their natural and unnatural history. p. 163. ISBN 0715349953.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "The Significance and Meaning of Owls in Japanese Culture". Owlcation.

- Deacy, Susan, and Villing, Alexandra (2001). Athena in the Classical World. Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands, ISBN 9004121420.

- Gimbutas, Marija (2001) The living goddesses, University of California Press, p. 158. ISBN 0520927095.

- Thiselton-Dyer, T. F. (1883) Folk-lore of Shakespeare, sacred-texts.com

- Keats, John. (1884) 49. Hyperion, in The Poetical Works of John Keats. Bartleby.com.

- Dubow, Charles (1 January 2004). "Hangover Cures". Forbes.

- Chopra, Capt. Praveen (2017). Vishnu's Mount: Birds In Indian Mythology And Folklore. Notion Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-948352-69-7.

- Lenders, E. W. (1914). "The Myth of the 'Wah-ru-hap-ah-rah,' or the Sacred Warclub Bundle". Zeitschrift für Ethnologie. 46: 404–420 (409).

- "Stikini, an owl monster of Seminole folklore". Native-languages.org. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- "Big Owl (Owl-Man), a malevolent Apache monster". Native-languages.org. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- "Native American Indian Owl Legends, Meaning and Symbolism from the Myths of Many Tribes". Native-languages.org. 25 July 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- "Mictlantecuhtli". Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- "Cuando el tecolote canta, el indio muere". La Cronica. 27 July 2008. Archived from the original on 3 September 2010.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "The Popol Vuh". meta-religion.com. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- "Owls". Hočąk Encyclopedia.

- Radin, Paul (1990 [1923]) The Winnebago Tribe, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, pp. 7–9 ISBN 0803257104.

- Smith, David Lee (1997) Folklore of the Winnebago Tribe, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, p. 160

- "Glory of the Morning", Hočąk Encyclopedia.

- "Owls in Lore and Culture". The Owl Pages. 31 October 2012. p. 3. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- "The Hungry Owl Project". Hungryowl.org. Archived from the original on 13 August 2003. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- "Man needed hospital treatment after owl attack". Daily Telegraph (London). 25 January 2013.

- Juvonen, Arto; Muukkonen, Tomi; Peltomäki, Jari; Varesvuo, Markku (2009). Linnut vauhdissa (in Finnish). Tammi. pp. 178, 187. ISBN 978-951-31-4604-7.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Harrison, Colin; Greensmith, Alan (1995). Koko maailman linnut (in Finnish). Translated by Laine, Lasse J.; Nikander, Pekka. Helsinki Media. p. 198. ISBN 951-875-637-6.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Wildlife Trade News – Huge haul of dead owls and live lizards in Peninsular Malaysia". TRAFFIC. 12 November 2008.

Further reading

- Calaprice, Alice & Heinrich, Bernd (1990): Owl in the House: A Naturalist's Diary. Joy Street Books, Boston. ISBN 0-316-35456-2

- Duncan, James. 2013. The Complete Book of North American Owls. Thunder Bay Press, San Diego. ISBN 9781607107262

- Duncan, James. 2003. Owls of the World. Key Porter Books, Toronto. ISBN 1552632148

- Heinrich, Bernd (1987): One Man's Owl

- Johnsgard, Paul A. (2002): North American Owls: Biology and Natural History, 2nd ed. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC. ISBN 1-56098-939-4.

- Maslow, Jonathan Evan (1983): The Owl Papers, 1st Vintage Books ed. Vintage Books, New York. ISBN 0-394-75813-7.

- Sibley, Charles Gald & Monroe, Burt L. Jr. (1990): Distribution and taxonomy of the birds of the world: A Study in Molecular Evolution. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. ISBN 0-300-04969-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Strigiformes. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Strigiformes. |

| Look up owl in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Eurasia:

- World of Owls – Northern Ireland's only owl, bird of prey and exotic animal centre

- Current Blakiston's Fish Owl Research in Russia

North America:

Oceania:

- iprimus info. re Australian owls and frogmouths