Farm Security Administration

The Farm Security Administration (FSA) was a New Deal agency created in 1937 to combat rural poverty during the Great Depression in the United States. It succeeded the Resettlement Administration (1935–1937).[1]

Farm Security Administration logo | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | September 1, 1937 |

| Preceding agencies | |

| Dissolved | 1946 |

| Superseding agency | |

| Key documents |

|

The FSA is famous for its small but highly influential photography program, 1935–44, that portrayed the challenges of rural poverty. The photographs in the FSA/Office of War Information Photograph Collection form an extensive pictorial record of American life between 1935 and 1944. This U.S. government photography project was headed for most of its existence by Roy Stryker, who guided the effort in a succession of government agencies: the Resettlement Administration (1935–1937), the Farm Security Administration (1937–1942), and the Office of War Information (1942–1944). The collection also includes photographs acquired from other governmental and nongovernmental sources, including the News Bureau at the Offices of Emergency Management (OEM), various branches of the military, and industrial corporations.[2]

In total, the black-and-white portion of the collection consists of about 175,000 black-and-white film negatives, encompassing both negatives that were printed for FSA-OWI use and those that were not printed at the time. Color transparencies also made by the FSA/OWI are available in a separate section of the catalog: FSA/OWI Color Photographs.[2]

The FSA stressed "rural rehabilitation" efforts to improve the lifestyle of very poor landowning farmers, and a program to purchase submarginal land owned by poor farmers and resettle them in group farms on land more suitable for efficient farming.

Reactionary critics, including the Farm Bureau, strongly opposed the FSA as an alleged experiment in collectivizing agriculture—that is, in bringing farmers together to work on large government-owned farms using modern techniques under the supervision of experts. After the Conservative coalition took control of Congress, it transformed the FSA into a program to help poor farmers buy land, and that program continues to operate in the 21st century as the Farmers Home Administration.

Origins

The projects that were combined in 1935 to form the Resettlement Administration (RA) started in 1933 as an assortment of programs tried out by the Federal Emergency Relief Administration. The RA was headed by Rexford Tugwell, an economic advisor to President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[3] However, Tugwell's goal moving 650,000 people into 100,000,000 acres (400,000 km2) of exhausted, worn-out land was unpopular among the majority in Congress.[3] This goal seemed socialistic to some and threatened to deprive powerful farm proprietors of their tenant workforce.[3] The RA was thus left with only enough resources to relocate a few thousand people from 9 million acres (36,000 km2) and build several greenbelt cities,[3] which planners admired as models for a cooperative future that never arrived.[3]

The main focus of the RA was to now build relief camps in California for migratory workers, especially refugees from the drought-stricken Dust Bowl of the Southwest.[3] This move was resisted by a large share of Californians, who did not want destitute migrants to settle in their midst.[3] The RA managed to construct 95 camps that gave migrants unaccustomed clean quarters with running water and other amenities,[3] but the 75,000 people who had the benefit of these camps were a small share of those in need and could only stay temporarily.[3] After facing enormous criticism for his poor management of the RA, Tugwell resigned in 1936.[3] On January 1, 1937,[4] with hopes of making the RA more effective, the RA was transferred to the Department of Agriculture through executive order 7530.[4]

On July 22, 1937,[5] Congress passed the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act.[5] This law authorized a modest credit program to assist tenant farmers to purchase land,[5] and it was the culmination of a long effort to secure legislation for their benefit.[5] Following the passage of the act, Congress passed the Farm Security Act into law. The Farm Security Act officially transformed the RA into the Farm Security Administration (FSA).[3] The FSA expanded through funds given by the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act.[3]

Relief work

One of the activities performed by the RA and FSA was the buying out of small farms that were not economically viable, and the setting up of 34 subsistence homestead communities, in which groups of farmers lived together under the guidance of government experts and worked a common area. They were not allowed to purchase their farms for fear that they would fall back into inefficient practices not guided by RA and FSA experts.[6]

The Dust Bowl in the Great Plains displaced thousands of tenant farmers, sharecroppers, and laborers, many of whom (known as "Okies" or "Arkies") moved on to California. The FSA operated camps for them, such as Weedpatch Camp as depicted in The Grapes of Wrath.

The RA and the FSA gave educational aid to 455,000 farm families during the period 1936-1943. In June, 1936, Roosevelt wrote: "You are right about the farmers who suffer through their own fault... I wish you would have a talk with Tugwell about what he is doing to educate this type of farmer to become self-sustaining. During the past year, his organization has made 104,000 farm families practically self-sustaining by supervision and education along practical lines. That is a pretty good record!"[7]

The FSA's primary mission was not to aid farm production or prices. Roosevelt's agricultural policy had, in fact, been to try to decrease agricultural production to increase prices. When production was discouraged, though, the tenant farmers and small holders suffered most by not being able to ship enough to market to pay rents. Many renters wanted money to buy farms, but the Agriculture Department realized there already were too many farmers, and did not have a program for farm purchases. Instead, they used education to help the poor stretch their money further. Congress, however, demanded that the FSA help tenant farmers purchase farms, and purchase loans of $191 million were made, which were eventually repaid. A much larger program was $778 million in loans (at effective rates of about 1% interest) to 950,000 tenant farmers. The goal was to make the farmer more efficient so the loans were used for new machinery, trucks, or animals, or to repay old debts. At all times, the borrower was closely advised by a government agent. Family needs were on the agenda, as the FSA set up a health insurance program and taught farm wives how to cook and raise children. Upward of a third of the amount was never repaid, as the tenants moved to much better opportunities in the cities.[8]

The FSA was also one of the authorities administering relief efforts in the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico during the Great Depression. Between 1938 and 1945, under the Puerto Rico Reconstruction Administration, it oversaw the purchase of 590 farms with the intent of distributing land to working and middle-class Puerto Ricans.[9]

Modernization

The FSA resettlement communities appear in the literature as efforts to ameliorate the wretched condition of southern sharecroppers and tenants, but those evicted to make way for the new settlers are virtually invisible in the historic record. The resettlement projects were part of larger efforts to modernize rural America. The removal of former tenants and their replacement by FSA clients in the lower Mississippi alluvial plain—the Delta—reveals core elements of New Deal modernizing policies. The key concepts that guided the FSA's tenant removals were: the definition of rural poverty as rooted in the problem of tenancy; the belief that economic success entailed particular cultural practices and social forms; and the commitment by those with political power to gain local support. These assumptions undergirded acceptance of racial segregation and the criteria used to select new settlers. Alternatives could only become visible through political or legal action—capacities sharecroppers seldom had. In succeeding decades, though, these modernizing assumptions created conditions for Delta African Americans on resettlement projects to challenge white supremacy.[10]

FSA and its contribution to society

The documentary photography genre describes photographs that would work as a time capsule for evidence in the future or a certain method that a person can use for a frame of reference. Facts presented in a photograph can speak for themselves after the viewer gets time to analyze it. The motto of the FSA was simply, as Beaumont Newhall insists, "not to inform us, but to move us." Those photographers wanted the government to move and give a hand to the people, as they were completely neglected and overlooked, thus they decided to start taking photographs in a style that we today call "documentary photography." The FSA photography has been influential due to its realist point of view, and because it works as a frame of reference and an educational tool from which later generations could learn. Society has benefited and will benefit from it for more years to come, as this photography can unveil the ambiguous and question the conditions that are taking place.[11]

Photography program

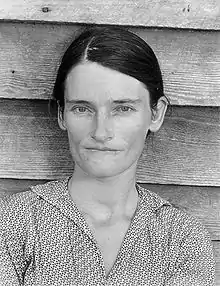

The RA and FSA are well known for the influence of their photography program, 1935–1944. Photographers and writers were hired to report and document the plight of poor farmers. The Information Division (ID) of the FSA was responsible for providing educational materials and press information to the public. Under Roy Stryker, the ID of the FSA adopted a goal of "introducing America to Americans." Many of the most famous Depression-era photographers were fostered by the FSA project. Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and Gordon Parks were three of the most famous FSA alumni.[12] The FSA was also cited in Gordon Parks' autobiographical novel, A Choice of Weapons.

The FSA's photography was one of the first large-scale visual documentations of the lives of African-Americans.[13] These images were widely disseminated through the 'Twelve Million Black Voices' collection, published in October 1941, which combined FSA photographs selected by Edwin Rosskam and text by author and poet Richard Wright.

Photographers

Eleven photographers came to work on this project (listed in order in which they were hired): Arthur Rothstein, Theo Jung, Ben Shahn, Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Carl Mydans, Russell Lee, Marion Post Wolcott, Jack Delano, John Vachon, and John Collier.

These 11 photographers all played a significant role, not only in producing images for this project, but also in molding the resulting images in the final project through conversations held between the group members. The photographers produced images that breathed a humanistic social visual catalyst of the sort found in novels, theatrical productions, and music of the time. Their images are now regarded as a "national treasure" in the United States, which is why this project is regarded as a work of art.[14]

Together with John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath (not a government project) and documentary prose (for example Walker Evans and James Agee's Let Us Now Praise Famous Men), the FSA photography project is most responsible for creating the image of the Depression in the United States. Many of the images appeared in popular magazines. The photographers were under instruction from Washington, DC, as to what overall impression the New Deal wanted to portray. Stryker's agenda focused on his faith in social engineering, the poor conditions among tenant cotton farmers, and the very poor conditions among migrant farm workers; above all, he was committed to social reform through New Deal intervention in people's lives. Stryker demanded photographs that "related people to the land and vice versa" because these photographs reinforced the RA's position that poverty could be controlled by "changing land practices." Though Stryker did not dictate to his photographers how they should compose the shots, he did send them lists of desirable themes, for example, "church", "court day", and "barns". Stryker sought photographs of migratory workers that would tell a story about how they lived day-to-day. He asked Dorothea Lange to emphasize cooking, sleeping, praying, and socializing.[15] RA-FSA made 250,000 images of rural poverty. Fewer than half of those images survive and are housed in the Prints and Photographs Division of the Library of Congress. The library has placed all 164,000 developed negatives online.[16] From these, some 77,000 different finished photographic prints were originally made for the press, plus 644 color images, from 1600 negatives.

Documentary films

The RA also funded two documentary films by Pare Lorentz: The Plow That Broke the Plains, about the creation of the Dust Bowl, and The River, about the importance of the Mississippi River. The films were deemed "culturally significant" by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.

World War II activities

During World War II, the FSA was assigned to work under the purview of the Wartime Civil Control Administration, a subagency of the War Relocation Authority. These agencies were responsible for relocating Japanese Americans from their homes on the West Coast to Internment camps. The FSA controlled the agricultural part of the evacuation. Starting in March 1942 they were responsible for transferring the farms owned and operated by Japanese Americans to alternate operators. They were given the dual mandate of ensuring fair compensation for Japanese Americans, and for maintaining correct use of the agricultural land. During this period, Lawrence Hewes Jr was the regional director and in charge of these activities.[17]

Reformers ousted; Farmers Home Administration

After the war started and millions of factory jobs in the cities were unfilled, no need for FSA remained. In late 1942, Roosevelt moved the housing programs to the National Housing Agency, and in 1943, Congress greatly reduced FSA's activities. The photographic unit was subsumed by the Office of War Information for one year, then disbanded. Finally in 1946, all the social reformers had left and FSA was replaced by a new agency, the Farmers Home Administration, which had the goal of helping finance farm purchases by tenants—and especially by war veterans—with no personal oversight by experts. It became part of Lyndon Johnson's war on poverty in the 1960s, with a greatly expanded budget to facilitate loans to low-income rural families and cooperatives, injecting $4.2 billion into rural America.[18]

The Great Depression

The Great Depression began in August 1929, when the United States economy first went into an economic recession. Although the country spent two months with declining GDP, the effects of a declining economy were not felt until the Wall Street Crash in October 1929, and a major worldwide economic downturn ensued.

Although its causes are still uncertain and controversial, the net effect was a sudden and general loss of confidence in the economic future and a reduction in living standards for most ordinary Americans. The market crash highlighted a decade of high unemployment, poverty, low profits for industrial firms, deflation, plunging farm incomes, and lost opportunities for economic growth.[19]

References

- Gabbert, Jim. "Resettlement Administration". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2013-05-24. Retrieved 2013-09-01.

- "Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives: About this Collection". Library of Congress. 1935.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - "Farm Security Administration". Novelguide. 2003. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved 2013-09-01.

- "Records of the Farmers Home Administration [FmHA]". Archives.gov. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- Archived January 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Baldwin 1968

- Sternsher 272

- Meriam pp. 290–312

- Dietz, James (1986). Economic History of Puerto Rico. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 200.

- Jane Adams and D. Gorton, "This Land Ain't My Land: The Eviction of Sharecroppers by the Farm Security Administration," Agricultural History Summer 2009, Vol. 83 Issue 3, pp. 323–51

- Bill Ganzel, "FSA photography," Farming in the 1930s (2003): 1–3.

- Hudson, Berkley (2009). Sterling, Christopher H. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Journalism. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE. pp. 1060–67. ISBN 978-0-7619-2957-4.

- Cossu-Beaumont, Laurence (30 December 2014). "Twelve Million Black Voices: Let Us Now Hear Black Voices". Transatlantica (2). doi:10.4000/transatlantica.7232.

- Rosenblum, Naomi, April Morganroth (2007). A World History of Photography (4th ed.). ISBN 9780789209375.

- Finnegan 43–44

- "164,000 RA-FSA photographs". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- Laurence I. Hewes, Final Report of the Participation of the Farm Security Administration in the Evacuation Program of the Wartime Civil Control Administration Civil Affairs Division Western Defense Command and Fourth Army, Farm Security Administration, United States Department of Agriculture, (San Francisco: 1942)

- Baldwin 403

- Gordon, John Steele. "10 Moments That Made American Business". American Heritage (February/March 2007). Archived from the original on 20 April 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

Further reading

Relief

- Sidney Baldwin, Poverty and Politics: The Rise and Decline of the Farm Security Administration. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1968

- Greta De Jong, "'With the Aid of God and the F.S.A.': The Louisiana Farmers' Union and the African American Freedom Struggle in the New Deal Era" Journal of Social History, Vol. 34, 2000

- Michael Johnston Grant, "Down and Out on the Family Farm: Rural Rehabilitation in the Great Plains, 1929–1945." Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2002

- Lewis Meriam, Relief and Social Security (Brookings Institution. 1946) pp 271–325.. online edition

- Charles Kenneth Roberts, Farm Security Administration and Rural Rehabilitation in the South. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press, 2015

- Theodore Saloutos, The American Farmer and the New Deal. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press, 1982

- Bernard Sternsher, Rexford Tugwell and the New Deal Rutgers University Press. 1964 Questia – The Online Library of Books and Journals

- James T. Young, "Origins of New Deal Agricultural Policy: Interest Groups' Role in Policy Formation." Policy Studies Journal. 21#2 1993. pp 190+. Questia – The Online Library of Books and Journals

Photography

- Maurice Berger, "FSA: The Illiterate Eye," in Berger, How Art Becomes History, HarperCollins, 1992

- Pete Daniel, et al., Official Images: New Deal Photography Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987

- James Curtis (1989). Mind's eye, mind's truth: FSA photography reconsidered. American civilization. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 978-0877226277.

- Cara A. Finnegan, Picturing Poverty: Print Culture and FSA Photographs Smithsonian Books, 2003

- Andrea Fisher, Let Us Now Praise Famous Women Pandora Press, 1987

- Carl Fleischhauer and Beverly W. Brannan, eds., Documenting America, 1935–1943 University of California Press, 1988.

- David A. Gray, "New Uses for Old Photos: Renovating FSA Photographs in World War II Posters," American Studies, 47: 3/4 (Fall/Winter 2006)

- James Guimond, American Photography and the American Dream (1991), chap. 4: "The Signs of Hard Times"

- Jack Hurley, Portrait of a Decade: Roy Stryker and the Development of Documentary Photography in the Thirties Louisiana State University Press, 1972

- Andrew Kelly, Kentucky by Design: The Decorative Arts and American Culture. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. 2015. ISBN 978-0-8131-5567-8

- Michael Leicht, Wie Katie Tingle sich weigerte, ordentlich zu posieren und Walker Evans darüber nicht grollte, Bielefeld: transcript 2006

- Dorothea Lange and Paul Schuster Taylor, An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion (1939); second revised edition, Yale University Press, 1969.

- Nicholas Natanson, The Black Image in the New Deal: The Politics of FSA Photography University of Tennessee Press, 1992

- Roy Stryker & Nancy Wood, In This Proud Land: America 1935–1943 As Seen In The FSA Photographs, Secker & Warburg/New York Graphic Society, 197

- Laurence Cossu-Beaumont, Twelve Million Black Voices: Let Us Now Hear Black Voices, Transatlantica (2) 2014 doi:10.4000/transatlantica.7232

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Farm Security Administration. |

- Farm Security Administration photograph collection, The Bancroft Library

- The Library of Congress has placed 164,000 FSA images online

- The New York Public Library has 2,581 FSA images online.

- Ralph W. Hollenberg collection of materials relating to the Farm Security Administration, The Bancroft Library

- During World War II the FSA administered the Use of farmland owned by interned Japanese farmers.

- Subsistence Homesteads by Survey Graphic

- High Resolution photos taken for the FSA

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture – Farm Security Administration

- Farm Security Administration

- Indiana Farm Security Administration Photographs

- "Sunny California" as sung by Americans who were supported by the FSA in 1941, from the World Digital Library

- Mary A. Sears collection of photographs pertaining to the Agricultural Workers Health and Medical Association in California, The Bancroft Library

.jpg.webp)