Social Security (United States)

In the United States, Social Security is the commonly used term for the federal Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) program and is administered by the Social Security Administration.[1] The original Social Security Act was signed into law by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935,[2] and the current version of the Act, as amended,[3] encompasses several social welfare and social insurance programs.

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Budget and debt in the United States of America |

|---|

|

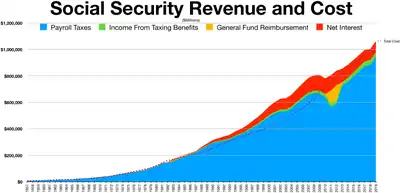

Social Security is funded primarily through payroll taxes called Federal Insurance Contributions Act tax (FICA) or Self Employed Contributions Act Tax (SECA). Tax deposits are collected by the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and are formally entrusted to the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund and the Federal Disability Insurance Trust Fund, the two Social Security Trust Funds.[4][5] These two trust funds purchase government securities, the interest income from which is used presently to fund the monthly allocations to qualifying citizens. With a few exceptions, all salaried income, up to an amount specifically determined by law (see tax rate table below), is subject to the Social Security payroll tax. All income over said amount is not taxed. In 2021, the maximum amount of taxable earnings is $142,800.[6]

With few exceptions, all legal residents working in the United States now have an individual Social Security number. Indeed, nearly all working (and many non-working) residents since Social Security's 1935 inception have had a Social Security number because it is requested by a wide range of businesses.

In 2017, Social Security expenditures totaled $806.7 billion for OASDI and $145.8 billion for DI.[7] Income derived from Social Security is currently estimated to have reduced the poverty rate for Americans age 65 or older from about 40% to below 10%.[8] In 2018, the trustees of the Social Security Trust Fund reported that the program will become financially insolvent in the year 2034 unless corrective action is enacted by Congress.[9] In 2020, the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania projected that the fund may be empty by 2032.[10]

History

| Historical Social Security Tax Rates Maximum Salary FICA or SECA taxes paid on | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Year | Maximum Earnings taxed | OASDI Tax rate | Medicare Tax Rate | Year | Maximum Earnings taxed | OASDI Tax rate | Medicare Tax Rate |

| 1937 | 3,000 | 2% | — | 1978 | 17,700 | 10.1% | 2.0% |

| 1938 | 3,000 | 2% | — | 1979 | 22,900 | 10.16% | 2.1% |

| 1939 | 3,000 | 2% | — | 1980 | 25,900 | 10.16% | 2.1% |

| 1940 | 3,000 | 2% | — | 1981 | 29,700 | 10.7% | 2.6% |

| 1941 | 3,000 | 2% | — | 1982 | 32,400 | 10.8% | 2.6% |

| 1942 | 3,000 | 2% | — | 1983 | 35,700 | 10.8% | 2.6% |

| 1943 | 3,000 | 2% | — | 1984 | 37,800 | 11.4% | 2.6% |

| 1944 | 3,000 | 2% | — | 1985 | 39,600 | 11.4% | 2.7% |

| 1945 | 3,000 | 2% | — | 1986 | 42,000 | 11.4% | 2.9% |

| 1946 | 3,000 | 2% | — | 1987 | 43,800 | 11.4% | 2.9% |

| 1947 | 3,000 | 2% | — | 1988 | 45,000 | 12.12% | 2.9% |

| 1948 | 3,000 | 2% | — | 1989 | 48,000 | 12.12% | 2.9% |

| 1949 | 3,000 | 2% | — | 1990 | 51,300 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1950 | 3,000 | 3% | — | 1991 | 53,400 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1951 | 3,600 | 3% | — | 1992 | 55,500 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1952 | 3,600 | 3% | — | 1993 | 57,600 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1953 | 3,600 | 3% | — | 1994 | 60,600 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1954 | 3,600 | 4% | — | 1995 | 61,200 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1955 | 4,200 | 4% | — | 1996 | 62,700 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1956 | 4,200 | 4% | — | 1997 | 65,400 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1957 | 4,200 | 4.5% | — | 1998 | 68,400 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1958 | 4,200 | 4.5% | — | 1999 | 72,600 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1959 | 4,800 | 5% | — | 2000 | 76,200 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1960 | 4,800 | 6% | — | 2001 | 80,400 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1961 | 4,800 | 6% | — | 2002 | 84,900 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1962 | 4,800 | 6.25% | — | 2003 | 87,000 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1963 | 4,800 | 7.25% | — | 2004 | 87,900 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1964 | 4,800 | 7.25% | — | 2005 | 90,000 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1965 | 4,800 | 7.25% | — | 2006 | 94,200 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1966 | 6,600 | 7.7% | 0.7% | 2007 | 97,500 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1967 | 6,600 | 7.8% | 1.0% | 2008 | 102,000 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1968 | 7,800 | 7.6% | 1.2% | 2009 | 106,800 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1969 | 7,800 | 8.4% | 1.2% | 2010 | 106,800 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1970 | 7,800 | 8.4% | 1.2% | 2011 | 106,800 | 10.4% | 2.9% |

| 1971 | 7,800 | 9.2% | 1.2% | 2012 | 110,100 | 10.4% | 2.9% |

| 1972 | 9,000 | 9.2% | 1.2% | 2013 | 113,700 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1973 | 10,800 | 9.7% | 2.0% | 2014 | 117,000 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1974 | 13,200 | 9.9% | 1.8% | 2015 | 118,500 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1975 | 14,100 | 9.9% | 1.8% | 2016 | 118,500 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1976 | 15,300 | 9.9% | 1.8% | 2017 | 127,200 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| 1977 | 16,500 | 9.9% | 1.8% | 2018 | 128,400 | 12.4% | 2.9% |

| Notes: Tax rate is the sum of the OASDI and Medicare rate for employers and workers. In 2011 and 2012, the OASDI tax rate on workers was set temporarily to 4.2% while the employers OASDI rate remained at 6.2% giving 10.4% total rate. Medicare taxes of 2.9% now (2013) have no taxable income ceiling. Sources: Social Security Administration[11][12] | |||||||

Social Security timeline[13]

- 1935 The 37-page Social Security Act signed August 14 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Retirement benefits only to worker, welfare benefits started

- 1936 The new Social Security Board contracts the Post Office Department in late November to distribute and collect applications.

- 1937 Over 20 million Social Security Cards issued. Ernest Ackerman receives first lump-sum payout (of 17 cents) in January.[14]

- 1939 Two new categories of beneficiaries added: spouse and minor children of a retired worker

- 1940 First monthly benefit check issued to Ida May Fuller for $22.54

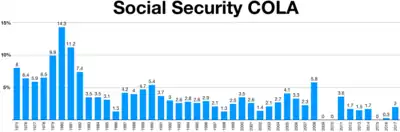

- 1950 Benefits increased and cost of living adjustments (COLAs) made at irregular intervals – 77% COLA in 1950

- 1954 Disability program added to Social Security

- 1960 Flemming v. Nestor. Landmark U.S. Supreme Court ruling that gave Congress the power to amend and revise the schedule of benefits. The Court also ruled that recipients have no contractual right to receive payments.

- 1961 Early retirement age lowered to age 62 at reduced benefits

- 1965 Medicare health care benefits added to Social security – 20 million joined in three years

- 1966 Medicare tax of 0.7% added to pay for increased Medicare expenses

- 1972 Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program federalized and assigned to Social Security Administration

- 1975 Automatic cost of living adjustments (COLAs) mandated

- 1977 COLA adjustments brought back to "sustainable" levels

- 1980 Amendments are made in disability program to help solve some problems of fraud

- 1983 Taxation of Social Security benefits introduced, new federal hires required to be under Social Security, retirement age increased for younger workers to 66 and 67 years

- 1984 Congress passed the Disability Benefits Reform Act modifying several aspects of the disability program

- 1996 Drug addiction or alcoholism disability benefits could no longer be eligible for disability benefits. The Earnings limit doubled exemption amount for retired Social Security beneficiaries. Terminated SSI eligibility for most non-citizens

- 1997 The law requires the establishment of federal standards for state-issued birth certificates and requires SSA to develop a prototype counterfeit-resistant Social Security card – still being worked on.

- 1997 Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, (TANF), replaces Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program placed under SSA

- 1997 State Children's Health Insurance Program for low income citizens – (SCHIP) added to Social Security Administration

- 2003 Voluntary drug benefits with supplemental Medicare insurance payments from recipients added

- 2009 No Social Security Benefits for Prisoners Act of 2009 signed.

A limited form of the Social Security program began, during President Franklin D. Roosevelt's first term, as a measure to implement "social insurance" during the Great Depression of the 1930s.[15] The Act was an attempt to limit unforeseen and unprepared-for dangers in modern life, including old age, disability, poverty, unemployment, and the burdens of widow(er)s with and without children.

Opponents, however, decried the proposal as socialism.[16][17][18] In a Senate Finance Committee hearing, Senator Thomas Gore (D-OK) asked Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, "Isn't this socialism?" She said that it was not, but he continued, "Isn't this a teeny-weeny bit of socialism?"[19]

The provisions of Social Security have been changing since the 1930s, shifting in response to economic worries as well as coverage for the poor, dependent children, spouses, survivors and the disabled.[20] By 1950, debates moved away from which occupational groups should be included to get enough taxpayers to fund Social Security to how to provide more benefits.[21] Changes in Social Security have reflected a balance between promoting "equality" and efforts to provide "adequate" and affordable protection for low wage workers.[22]

Major programs

The larger and better known programs under the Social Security Administration, SSA, are:

- Federal Old-Age (Retirement), Survivors, and Disability Insurance, OASDI

- Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, TANF

- Health Insurance for Aged and Disabled, Medicare

- Grants to States for Medical Assistance Programs for low income citizens, Medicaid

- State Children's Health Insurance Program for low income citizens, SCHIP

- Supplemental Security Income, SSI

Benefits

Benefits and Income 2020

| 2013 Social Security Trustee Report All funds in billions of dollars[23] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Category | Retirement OASI | Disability DI | Medicare Part A HI | Medicare Part B & D SMI |

| Income during 2012 | 731.1 | 109.1 | 243.0 | 293.9 |

| Total paid 2012 | 645.4 | 140.3 | 266.8 | 307.4 |

| Net change in Reserves | 85.6 | −31.2 | −23.8 | −13.5 |

| Reserves (end of 2012) | 2,609.7 | 122.7 | 220.4 | 67.2 |

| Benefit payments | 637.9 | 136.9 | 262.9 | 303.0 |

| Railroad Retirement accounts | 4.1 | 0.5 | — | — |

| Administrative expenses | 3.4 | 2.9 | 3.9 | 4.4 |

| Social Security Income | ||||

| Payroll taxes | 503.9 | 85.6 | 205.7 | — |

| Taxes on OASDI benefits | 26.7 | 0.6 | 18.6 | — |

| Beneficiary premiums | — | — | 3.7 | 66.6 |

| Transfers from States | — | — | — | 8.4 |

| General Fund reimbursements | 97.7 | 16.5 | 0.5 | — |

| General revenue transfers1 | — | — | — | 214.8 |

| Interest earnings | 102.8 | 6.4 | 10.6 | 2.8 |

| Other | — | 3.9 | 2.2 | |

| Total | 731.1 | 109.1 | 243.0 | 293.9 |

1. To prevent Social Security from losing tax revenue during the reduced Social Security worker 2.0% tax rate reduction in 2011 and 2012, Congress borrowed money from the federal general tax fund and transferred it to the Social Security trust funds. Sources: Social Security Administration,[24] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)[25] | ||||

The largest component of OASDI is the payment of retirement benefits. These retirement benefits are a form of social insurance that is heavily biased toward lower paid workers to make sure they do not have to retire in relative poverty. With few exceptions, throughout a worker's career, the Social Security Administration and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) keeps track of his or her earnings and requires Federal Insurance Contribution Act, FICA or Self Employed Contribution Act, SECA, taxes to be paid on the earnings. The OASI accounts plus trust funds are the only Social Security funding source that brings in more than it sends out.

Social Security revenues exceeded expenditures between 1983 and 2009.[26]

The disability insurance (DI) taxes of 1.4% are included in the OASDI rate of 6.2% for workers and employers or 12.4% for the self-employed. Outgo of $140.3 billion while having income of only $109.1 billion means the disability trust fund is rapidly being depleted and may require either revisions on what "disabilities" are included/allowed/defined as, fraud minimization, or tax increases.

The Medicare hospital insurance, HI (Part A: Hospital Insurance, inpatient care, skilled nursing facility care, home health care, and hospice care), expenditure rate of $266.8 billion in 2012—while bringing in only $243.0 billion—means that the Medicare HI trust funds are being seriously depleted and increased taxes or reduced coverage will be required. The additional retirees expected under the "baby boom bulge" will hasten this trust fund depletion. Medicare expenses, tied to medical costs growth rates, have traditionally increased much faster than GDP growth rates.[27]

The Supplementary Medical Insurance, SMI (otherwise known as Medicare Part B & D), expenditure rate of $307.4 billion in 2012 while bringing in only $293.9 billion means that the Supplementary Medical Insurance trust funds are also being seriously depleted and increased tax rates or reduced coverage will be required. The additional retirees expected under the "baby boom bulge" will hasten this trust fund depletion as well as legislation to end the Medicare Part D medical prescription drug funding "donut hole" are all tied to medical costs growth rates, which have traditionally increased much faster than GDP growth rates.[27]

For workers the Social Security tax rate is 6.2% on income under $127,200 through the end of 2017.[6] The worker Medicare tax rate is 1.45% of all income—employers pay another 1.45%. Employers pay 6.2% up to the wage ceiling and the Medicare tax of 1.45 percent on all income. Workers defined as "self employed" pay 12.4% on income under $113,700 and a 2.9% Medicare tax on all income.

The amount of the monthly Social Security benefit to which a worker is entitled depends upon the earnings record they have paid FICA or SECA taxes on and upon the age at which the retiree chooses to begin receiving benefits.

Total benefits paid, by year

| Year | Beneficiaries | Dollars[28] |

|---|---|---|

| 1937 | 53,236 | $1,278,000 |

| 1938 | 213,670 | $10,478,000 |

| 1939 | 174,839 | $13,896,000 |

| 1940 | 222,488 | $35,000,000 |

| 1950 | 3,477,243 | $961,000,000 |

| 1960 | 14,844,589 | $11,245,000,000 |

| 1970 | 26,228,629 | $31,863,000,000 |

| 1980 | 35,584,955 | $120,511,000,000 |

| 1990 | 39,832,125 | $247,796,000,000 |

| 1995 | 43,387,259 | $332,553,000,000 |

| 1996 | 43,736,836 | $347,088,000,000 |

| 1997 | 43,971,086 | $361,970,000,000 |

| 1998 | 44,245,731 | $374,990,000,000 |

| 1999 | 44,595,624 | $385,768,000,000 |

| 2000 | 45,414,794 | $407,644,000,000 |

| 2001 | 45,877,506 | $431,949,000,000 |

| 2002 | 46,444,317 | $453,746,000,000 |

| 2003 | 47,038,486 | $470,778,000,000 |

| 2004 | 47,687,693 | $493,263,000,000 |

| 2005 | 48,434,436 | $520,748,000,000 |

| 2006 | 49,122,624 | $546,238,000,000 |

| 2007 | 49,864,838 | $584,939,000,000 |

| 2008 | 50,898,244 | $615,344,000,000 |

Primary Insurance Amount and benefit calculations

All workers paying FICA (Federal Insurance Contributions Act) and SECA (Self Employed Contributions Act) taxes for forty quarters of coverage (QC) or more on a specified minimum income or more are "fully insured" and eligible to retire at age 62 with reduced benefits and higher benefits at full retirement ages, FRA, of 65, 66 or 67 depending on birth date.[29] Retirement benefits depend upon the "adjusted" average wage earned in the last 35 years. Wages of earlier years are "adjusted" before averaging by multiplying each annual salary by an annual adjusted wage index factor, AWI, for earlier salaries.[30] Adjusted wages for 35 years are always used to compute the 35 year "average" indexed monthly salary. Only wages lower than the "ceiling" income are considered in calculating the adjusted average wage. If the worker has fewer than 35 years of covered earnings these non-contributory years are assigned zero earnings. If there are more than 35 years of covered earnings only the highest 35 are considered. The sum of the 35 adjusted salaries (or less if worker has less than 35 years of covered income) times its inflation index, AWI divided by 420 (35 years x 12 months per year) gives the 35-year covered Average Indexed Monthly salary, AIME.[30]

To calculate a person's Average Indexed Monthly salary (AIME) earnings, A detailed earnings summary may be obtained from the Social Security Administration by requesting it and paying a fee of $91.00.[31] The adjusted wage indexes are available at Social Security's "Benefit Calculation Examples For Workers Retiring In 2013".[32]

| Benefit Calculations Social Security Benefits vs. 35-year "Averaged" Salary Percent of Average Indexed Monthly salary (AIME) Earnings Salary eligible for in Social Security, PIA, Benefits[33] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| AIME Salary per month | Single Benefits | Married Benefits* | Single Benefits at age 62 | Married Benefits* at age 62 |

| $ 791 | 90% | 135% | 68% | 101% |

| $ 1,000 | 78% | 117% | 58% | 88% |

| $ 2,000 | 55% | 82% | 41% | 62% |

| $ 3,000 | 47% | 71% | 35% | 53% |

| $ 4,000 | 43% | 65% | 33% | 49% |

| $ 5,000 | 40% | 60% | 30% | 45% |

| $ 6,000 | 36% | 54% | 27% | 41% |

| $ 7,000 | 33% | 50% | 25% | 32% |

| $ 8,000 | 31% | 46% | 23% | 35% |

| $ 9,000 | 29% | 44% | 22% | 33% |

| $ 10,000 | 28% | 42% | 21% | 31% |

| $ 11,000 | 23% | 34% | 17% | 26% |

| $ 12,000 | 21% | 32% | 16% | 24% |

| $ 13,000 | 19% | 29% | 15% | 22% |

| * Married spousal benefits may be reduced or eliminated if spouse receiving a government pension. Spouse still eligible for Medicare.[34] Maximum percent of salary received before Medicare or tax deductions. Retirement benefits are calculated at full retirement ages. Age 62 retirement benefits are assumed to be 75% of full benefits. Approximately AIME salary = 90% present salary. Approximate only, contact Social Security for more detailed calculations. | ||||

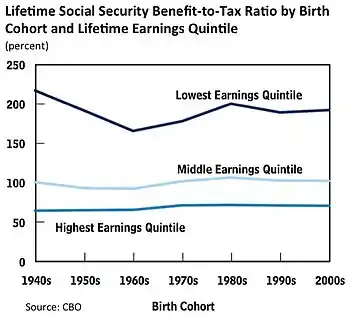

To calculate the total benefits a retiree is eligible for, the average indexed monthly salary (AIME) is then divided into three separate salary brackets—each multiplied by a different benefit percentage. The benefits receivable (the so-called Primary Insurance Amount, PIA) are the sum of the salary in each bracket times the benefit percentages that apply to each bracket. The benefit percentages are set by Congress and so can easily change in the future. The bendpoints, where the brackets change, are adjusted for inflation each year by Social Security. For example, in 2013 the first bracket runs from $1 to $791/month and is multiplied by the benefit percentage of 90%, the second salary bracket extends from $791 to $4,781/month is multiplied by 32%, the third salary bracket of more than $4,781/month is multiplied by 15%. Any higher incomes than the ceiling income are not FICA covered and are not considered in the benefits calculation or in determining the average indexed monthly salary, AIME. At full retirement age the projected retirement income amount (PIA) is the sum of these three brackets of income multiplied by the appropriate benefit percentages—90%, 32% and 15%. Unlike income tax brackets, the Social Security benefits are heavily biased towards lower salaried workers. Social Security has always been primarily a retirement, disability and spousal insurance policy for low wage workers and a very poor retirement plan for higher salaried workers who hopefully have a supplemental retirement plan unless they want to live on significantly less after retirement than they used to earn.

Full retirement age spouses and divorced spouses (who were married for at least 10 years before divorce to a worker who is eligible) are entitled to the higher of 50% of the wage earners benefits or their own earned benefits. A low salary worker and his full retirement age spouse making less than or equal to $791/month with 40 quarters of employment credit and at full retirement age (65 if born before 1938, 66 if born from 1938 to 1954 and 67 if born after 1960) could retire with 135% of his indexed average salary. A full retirement age worker and his full retirement age spouse making the ceiling income or more would be eligible for 43% of the ceiling FICA salary (29% if single) and even less if making more than the ceiling income.

During working years, the low wage worker is eligible for the Earned Income Tax Credit (FICA refunds) and federal child credits and may pay little or no FICA tax or Income tax. By Congressional Budget Office (CBO) calculations the lowest income quintile (0–20%) and second quintile (21–40%) of households in the U.S. pay an average income tax of −9.3% and −2.6% and Social Security taxes of 8.3% and 7.9% respectively. By CBO calculations the household incomes in the first quintile and second quintile have an average Total Federal Tax rate of 1.0% and 3.8% respectively.[35] Higher income retirees will have to pay income taxes on 85% of their Social Security benefits and 100% on all other retirement benefits they may have.[30]

All workers paying FICA and SECA taxes for forty quarters of credit (QC) or more on a specified minimum income is "fully insured" and eligible to retire at age 62 with reduced benefits.[29][36] In general the Social Security Administration tries to limit the projected lifetime benefits to the same amounts of retirement income the recipient would receive if retiring at full retirement age. If a recipient retires earlier he/she draws a lower Social Security benefit income for a longer prospective lifetime after retirement. The basic correction of benefits are age 62 retirees can only draw 75% of what they would draw at full retirement age with higher percentages at different ages more than 62 and less than full retirement age.

Similar computations based on career average adjusted earnings and age of recipient determine disability and survivor benefits.[37] Federal, state and local employees who have elected (when they could) NOT to pay FICA taxes are eligible for a reduced FICA benefits and full Medicare coverage if they have more than forty quarters of qualifying Social Security covered work.[29] To minimize the Social Security payments to those who have not contributed to FICA for 35+ years and are eligible for federal, state and local benefits, which are usually more generous, Congress passed the Windfall Elimination Provision, WEP.[38] The WEP provision will not eliminate all Social Security or Medicare eligibility if the worker has 40 quarters of qualifying income, but calculates the benefit payments by reducing the 90% multiplier in the first PIA bendpoint to 40–85% depending on the number of Years of Coverage.[39] Foreign pensions are subject to WEP.

For those few cases where workers with very low earnings over a long working lifetime that were too low to receive full retirement credits[40] and the recipients would receive a very small Social Security retirement benefit a "special minimum benefit" (special minimum PIA) provides a "minimum" of $804 per month in Social Security benefits in 2013. To be eligible the recipient along with their auxiliaries and survivors must have very low assets and not be eligible for other retirement system benefits. About 75,000 people in 2013 receive this benefit.[40][41]

The benefits someone is eligible for are potentially so complicated that potential retirees should consult the Social Security Administration directly for advice. Many questions are addressed and at least partially answered on many online publications and online calculators.

Online benefits estimate

On July 22, 2008, the Social Security Administration introduced a new online benefits estimator.[42][43] A worker who has enough Social Security credits to qualify for benefits, but who is not currently receiving benefits on his or her own Social Security record and who is not a Medicare beneficiary, can obtain an estimate of the retirement benefit that will be provided, for different assumptions about age at retirement. This process is done by opening a secure online account called my Social Security. For retirees who have non FICA or SECA taxed wages the rules get complicated and probably require additional help.

Normal retirement age

The earliest age at which (reduced) benefits are payable is 62. Full retirement benefits depend on a retiree's year of birth.[44]

| Year of birth | Normal retirement age |

|---|---|

| 1937 and prior | 65 |

| 1938 | 65 and 2 months |

| 1939 | 65 and 4 months |

| 1940 | 65 and 6 months |

| 1941 | 65 and 8 months |

| 1942 | 65 and 10 months |

| 1943 to 1954 | 66 |

| 1955 | 66 and 2 months |

| 1956 | 66 and 4 months |

| 1957 | 66 and 6 months |

| 1958 | 66 and 8 months |

| 1959 | 66 and 10 months |

| 1960 and later | 67 |

| Age when filing | Change in benefits from full amount[45] |

|---|---|

| 62 | -25% |

| 63 | -20% |

| 64 | -13.3% |

| 65 | -6.7% |

| 66 | ---- |

| 67 | +8% |

| 68 | +16% |

| 69 | +24% |

| 70 | +32% |

| Based on a normal retirement age of 66 | |

This table was copied in November 2011 from the Social Security Administration web site cited above and referenced in the footnotes. There are different rules for widows and widowers. Also from that site, come the following two notes: Notes: 1. Persons born on January 1 of any year should refer to the normal retirement age for the previous year. 2. For the purpose of determining benefit reductions for early retirement, widows and widowers whose entitlement is based on having attained age 60 should add 2 years to the year of birth shown in the table.

Those born before 1938 have a normal retirement age of 65. Normal retirement age increases by two months for each ensuing year of birth until 1943, when it reaches 66 and stays at 66 until 1955. Thereafter the normal retirement age increases again by two months for each year until 1960, when normal retirement age is 67 and remains 67 for all individuals born thereafter.

A worker who starts benefits before normal retirement age has their benefit reduced based on the number of months before normal retirement age they start benefits. This reduction is 5/9 of 1% for each month up to 36 and then 5/12 of 1% for each additional month. This formula gives an 80% benefit at age 62 for a worker with a normal retirement age of 65, a 75% benefit at age 62 for a worker with a normal retirement age of 66, and a 70% benefit at age 62 for a worker with a normal retirement age of 67. The Great Recession has resulted in an increase in long-term unemployment and an increase in workers taking early retirement.[46]

A worker who delays starting retirement benefits past normal retirement age earns delayed retirement credits that increase their benefit until they reach age 70. These credits are also applied to their widow(er)'s benefit. Children and spouse benefits are not affected by these credits.

The normal retirement age for widow(er) benefits shifts the year-of-birth schedule upward by two years, so that those widow(er)s born before 1940 have age 65 as their normal retirement age.

Spouse's benefit and government pension offsets

The spousal retirement benefit is one-half the "primary insurance amount" PIA[47] benefit amount of their spouse or their own earned benefits, whichever is higher, if they both retire at "normal" retirement ages. Only after the working spouse applies for retirement benefits may the non-working spouse apply for spousal retirement benefits. The spousal benefit is the PIA times an "early-retirement factor" if the spouse is younger than the "normal" full retirement age. The early-retirement factor is 50% minus 25/36 of 1% per month for the first 36 months and 5/12 of 1% for each additional month earlier than the "normal" full retirement date. This typically works out to between 50% and 32.5% of the primary workers full retirement age the projected retirement income amount (PIA) benefit with no additional spousal benefits when the primary worker retires after the normal full retirement date.[48] There is no increase for starting spousal benefits after full retirement age. A spouse is eligible, after a one-year duration of marriage is met and divorced or former spouses are eligible for spousal benefits if the marriage lasted for at least 10 years and the person applying is not currently married. It is arithmetically possible for one worker to generate spousal benefits for up to five of his/her spouses that he/she may have, each must be in succession after a proper divorce for each after a marriage that lasted at least ten years each.

There is a Social Security government pension offset[49] that will reduce or eliminate any spousal (or ex-spouse) or widow(er)'s benefits if the spouse or widow(er) is also receiving a government (federal, state, or local) pension that did not require paying Social Security taxes. The basic rule is that Social Security benefits will be reduced by 2/3's of the spouse or widow(er)'s non-FICA taxed government pension. If the spouse's or widow(er)'s government (non-FICA paying) pension exceeds 150% of the "normal" spousal or widow(er)'s benefit the spousal benefit is eliminated. For example, a "normal" spousal or widow(er)'s benefit of $1,000/month would be reduced to $0.00 if the spouse or widow(er)'s if already drawing a non-FICA taxed government pension of $1,500/month or more per month. Pensions not based on income do not reduce Social Security spousal or widow(er)'s benefits. Pensions received from foreign countries do not cause GPO; however, a foreign pension may be subject to the WEP.[50]

The passage of the Senior Citizens' Freedom to Work Act, in 2000, allows the worker to earn unlimited outside income without offsets in the year after they reach full retirement. It also allows the spouse and children of a worker who has reached normal full retirement age to receive benefits under some circumstances while he/she does not. The full retirement age worker must have begun the receipt of benefits, to allow the spousal/children's benefits to begin, and then subsequently suspended their own benefits in order to continue the postponement of benefits in exchange for an increased benefit amount (5.5–8.0%/yr increase)[51] up to the age of 70. Thus a worker can delay retirement up to age seventy without affecting spousal or children's benefits.[52]

Delayed benefits

| Delayed Social Security Increases for retiring after full retirement age[51] | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Year of birth | Yearly % increase | Monthly % increase |

| 1933–34 | 5.5% | 11/24 of 1% |

| 1935–36 | 6.0% | 1/2 of 1% |

| 1937–38 | 6.5% | 13/24 of 1% |

| 1939–40 | 7.0% | 7/12 of 1% |

| 1941–42 | 7.5% | 5/8 of 1% |

| 1943+ | 8.0% | 2/3 of 1% |

If a worker delays receiving Social Security retirement benefits until after they reach full retirement age,[51] the benefit will increase by two-thirds of one percent of the PIA per month.[53] After age 70 there are no more increases as a result of delaying benefits. Social Security uses an "average" survival rate at your full retirement age to prorate the increase in the amount of benefit increase so that the total benefits are roughly the same whenever you retire. Women may benefit more than men from this delayed benefit increase since the "average" survival rates are based on both men and women and women live approximately three years longer than men. The other consideration is that workers only have a limited number of years of "good" health left after they reach full retirement age and unless they enjoy their job they may be passing up an opportunity to do something else they may enjoy doing while they are still relatively healthy.

Benefits while continuing work

Due to changing needs or personal preferences, a person may go back to work after retiring. In this case, it is possible to get Social Security retirement or survivors benefits and work at the same time. A worker who is of full retirement age or older may (with spouse) keep all benefits, after taxes, regardless of earnings. But, if this worker or the worker's spouse are younger than full retirement age and receiving benefits and earn "too much", the benefits will be reduced. If working under full retirement age for the entire year and receiving benefits, Social Security deducts $1 from the worker's benefit payments for every $2 earned above the annual limit of $15,120 (2013). Deductions cease when the benefits have been reduced to zero and the worker will get one more year of income and age credit, slightly increasing future benefits at retirement. For example, if you were receiving benefits of $1,230/month (the average benefit paid) or $14,760 a year and have an income of $29,520/year above the $15,120 limit ($44,640/year) you would lose all ($14,760) of your benefits. If you made $1,000 more than $15,200/year you would "only lose" $500 in benefits. You would get no benefits for the months you work until the $1 deduction for $2 income "squeeze" is satisfied. Your first social security check will be delayed for several months—the first check may only be a fraction of the "full" amount. The benefit deductions change in the year you reach full retirement age and are still working—Social Security only deducts $1 in benefits for every $3 you earn above $40,080 in 2013 for that year and has no deduction thereafter. The income limits change (presumably for inflation) year by year.[54]

Widow(er) benefits

If a worker covered by Social Security dies, a surviving spouse can receive survivors' benefits if a 9-month duration of marriage is met. If a widow waits until Full Retirement Age, they are eligible for 100 percent of their deceased spouse's PIA. If the death of the worker was accidental the duration of marriage test may be waived.[55] A divorced spouse may qualify if the duration of marriage was at least 10 full years and the widow(er) is not currently married, or remarried after attainment of age 60 (50 if disabled and eligible for specific types of benefits[56] prior to the date of marriage). A father or mother of any age with a child age 16 or under or a disabled adult child in his or her care may be eligible for benefits. The earliest age for a non-disabled widow(er)'s benefit is age 60. If the worker received retirement benefits prior to death, the benefit amount may not exceed the amount the worker was receiving at the time of death or 82.5% of the PIA of the deceased worker (whichever is more).[57] If the surviving spouse starts benefits before full retirement age, there is an actuarial reduction.[58] If the worker earned delayed retirement credits by waiting to start benefits after their full retirement age, the surviving spouse will have those credits applied to their benefit.[59] If the worker died before the year of attainment of age 62, the earnings will be indexed to the year in which the surviving spouse attained age 60.[60]

Children's benefits

Children of a retired, disabled or deceased worker receive benefits as a "dependent" or "survivor" if they are under the age of 18, or as long as attending primary or secondary school up to age 19 years, 2 months; or are over the age of 18 and were disabled before the age of 22.[58][61]

The benefit for a child on a living parent's record is 50% of the PIA, for a surviving child the benefit is 75% of the PIA. The benefit amount may be reduced if total benefits on the record exceed the family maximum.

In Astrue v. Capato (2012), the Supreme Court unanimously held that children conceived after a parent's death (by in vitro fertilization procedure) are not entitled to Social Security survivors' benefits if the laws of the state in which the parent's will was signed do not provide for such benefits.[62]

Disability

A worker who has worked long enough and recently enough (based on "quarters of coverage" within the recent past) to be covered can receive disability benefits. These benefits start after five full calendar months of disability, regardless of his or her age. The eligibility formula requires a certain number of credits (based on earnings) to have been earned overall, and a certain number within the ten years immediately preceding the disability, but with more-lenient provisions for younger workers who become disabled before having had a chance to compile a long earnings history.

The worker must be unable to continue in his or her previous job and unable to adjust to other work, with age, education, and work experience taken into account; furthermore, the disability must be long-term, lasting 12 months, expected to last 12 months, resulting in death, or expected to result in death.[63] As with the retirement benefit, the amount of the disability benefit payable depends on the worker's age and record of covered earnings.

Supplemental Security Income (SSI) uses the same disability criteria as the insured social security disability program, but SSI is not based upon insurance coverage. Instead, a system of means-testing is used to determine whether the claimants' income and net worth fall below certain income and asset thresholds.

Severely disabled children may qualify for SSI. Standards for child disability are different from those for adults.

Disability determination at the Social Security Administration has created the largest system of administrative courts in the United States. Depending on the state of residence, a claimant whose initial application for benefits is denied can request reconsideration or a hearing before an Administrative Law Judge (ALJ). Such hearings sometimes involve participation of an independent vocational expert (VE) or medical expert (ME), as called upon by the ALJ.

Reconsideration involves a re-examination of the evidence and, in some cases, the opportunity for a hearing before a (non-attorney) disability hearing officer. The hearing officer then issues a decision in writing, providing justification for his/her finding. If the claimant is denied at the reconsideration stage, (s)he may request a hearing before an Administrative Law Judge. In some states, SSA has implemented a pilot program that eliminates the reconsideration step and allows claimants to appeal an initial denial directly to an Administrative Law Judge.

Because the number of applications for Social Security disability is very large (approximately 650,000 applications per year), the number of hearings requested by claimants often exceeds the capacity of Administrative Law Judges. The number of hearings requested and availability of Administrative Law Judges varies geographically across the United States. In some areas of the country, it is possible for a claimant to have a hearing with an Administrative Law Judge within 90 days of his/her request. In other areas, waiting times of 18 months are not uncommon.

After the hearing, the Administrative Law Judge (ALJ) issues a decision in writing. The decision can be Fully Favorable (the ALJ finds the claimant disabled as of the date that (s) he alleges in the application through the present), Partially Favorable (the ALJ finds the claimant disabled at some point, but not as of the date alleged in the application; OR the ALJ finds that the claimant was disabled but has improved), or Unfavorable (the ALJ finds that the claimant was not disabled at all). Claimants can appeal decisions to Social Security's Appeals Council, which is in Virginia. The Appeals Council does not hold hearings; it accepts written briefs. Response time from the Appeals Council can range from 12 weeks to more than 3 years.

If the claimant disagrees with the Appeals Council's decision, (s)he can appeal the case in the federal district court for his/her jurisdiction. As in most federal court cases, an unfavorable district court decision can be appealed to the appropriate United States Court of Appeals, and an unfavorable appellate court decision can be appealed to the United States Supreme Court.

The Social Security Administration has maintained its goal for judges to resolve 500–700 cases per year but an Administrative Law Judge on the average nationwide disposes of approximately 400 cases per year. The debate about the social security system in the United States has been ongoing for decades and there is much concern about its sustainability.[64][65]

Current operation

Joining and quitting

Obtaining a Social Security number for a child is voluntary.[66] Further, there is no general legal requirement that individuals join the Social Security program unless they want or have to work. Under normal circumstances, FICA taxes or SECA taxes will be collected on all wages. About the only way to avoid paying either FICA or SECA taxes is to join a religion that does not believe in insurance, such as the Amish or a religion whose members have taken a vow of poverty (see IRS publication 517[67] and 4361[68]). Federal workers employed before 1987, various state and local workers including those in some school districts who had their own retirement and disability programs were given the one-time option of joining Social Security. Many employees and retirement and disability systems opted to keep out of the Social Security system because of the cost and the limited benefits. It was often much cheaper to obtain much higher retirement and disability benefits by staying in their original retirement and disability plans.[69] Now only a few of these plans allow new hires to join their existing plans without also joining Social Security. In 2004, the Social Security Administration estimated that 96% of all U.S. workers were covered by the system with the remaining 4% mostly a minority of government employees enrolled in public employee pensions and not subject to Social Security taxes due to historical exemptions.[70]

It is possible for railroad employees to get a "coordinated" retirement and disability benefits. The U.S. Railroad Retirement Board (or "RRB") is an independent agency in the executive branch of the United States government created in 1935[71] to administer a social insurance program providing retirement benefits to the country's railroad workers. Railroad retirement Tier I payroll taxes are coordinated with social security taxes so that employees and employers pay Tier I taxes at the same rate as social security taxes and have the same benefits. In addition, both workers and employers pay Tier II taxes (about 6.2% in 2005), which are used to finance railroad retirement and disability benefit payments that are over and above social security levels. Tier 2 benefits are a supplemental retirement and disability benefit system that pays 0.875% times years of service times average highest five years of employment salary, in addition to Social Security benefits.

The FICA taxes are imposed on nearly all workers and self-employed persons. Employers are required[72] to report wages for covered employment to Social Security for processing Forms W-2 and W-3. Some specific wages are not part of the Social Security program (discussed below). Internal Revenue Code provisions section 3101[73] imposes payroll taxes on individuals and employer matching taxes. Section 3102[74] mandates that employers deduct these payroll taxes from workers' wages before they are paid. Generally, the payroll tax is imposed on everyone in employment earning "wages" as defined in 3121[75] of the Internal Revenue Code.[76] and also taxes[77] net earnings from self-employment.[78]

Trust fund

Social Security taxes are paid into the Social Security Trust Fund maintained by the U.S. Treasury (technically, the "Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund", as established by ). Current year expenses are paid from current Social Security tax revenues. When revenues exceed expenditures, as they did between 1983 and 2009,[26] the excess is invested in special series, non-marketable U.S. government bonds. Thus, the Social Security Trust Fund indirectly finances the federal government's general purpose deficit spending. In 2007, the cumulative excess of Social Security taxes and interest received over benefits paid out stood at $2.2 trillion.[79] Some regard the Trust Fund as an accounting construct with no economic significance. Others argue that it has specific legal significance because the Treasury securities it holds are backed by the "full faith and credit" of the U.S. government, which has an obligation to repay its debt.[80]

The Social Security Administration's authority to make benefit payments as granted by Congress extends only to its current revenues and existing Trust Fund balance, i.e., redemption of its holdings of Treasury securities. Therefore, Social Security's ability to make full payments once annual benefits exceed revenues depends in part on the federal government's ability to make good on the bonds that it has issued to the Social Security trust funds. As with any other federal obligation, the federal government's ability to repay Social Security is based on its power to tax and borrow and the commitment of Congress to meet its obligations.

In 2009 the Office of the Chief Actuary of the Social Security Administration calculated an unfunded obligation of $15.1 trillion for the Social Security program. The unfunded obligation is the difference between the future cost of Social Security (based on several demographic assumptions such as mortality, work force participation, immigration, and age expectancy) and total assets in the Trust Fund given the expected contribution rate through the current scheduled payroll tax. This unfunded obligation is expressed in present value dollars and is a part of the Fund's long-range actuarial estimates, not necessarily a certainty of what will occur in the long run. An Actuarial Note to the calculation says that "The term obligation is used in lieu of the term liability, because liability generally indicates a contractual obligation (as in the case of private pensions and insurance) that cannot be altered by the plan sponsor without the agreement of the plan participants."[81][82]

Office of Hearings Operations (OHO, formerly ODAR or OHA)

On August 8, 2017, Acting Commissioner Nancy A. Berryhill informed employees that the Office of Disability Adjudication and Review ("ODAR") would be renamed to Office of Hearings Operations ("OHO").[83] The hearing offices had been known as "ODAR" since 2006, and the Office of Hearings and Appeals ("OHA") before that. OHO administers the ALJ hearings for the Social Security Administration.[84] Administrative Law Judges ("ALJs") conduct hearings and issue decisions. After an ALJ decision, the Appeals Council considers requests for review of ALJ decisions, and acts as the final level of administrative review for the Social Security Administration (the stage at which "exhaustion" could occur, a prerequisite for federal court review).[85]

Benefit payout comparisons

Some federal, state, local and education government employees pay no Social Security but have their own retirement, disability systems that nearly always pay much better retirement and disability benefits than Social Security. These plans typically require vesting—working for 5–10 years for the same employer before becoming eligible for retirement. But their retirement typically only depends on the average of the best 3–10 years salaries times some retirement factor (typically 0.875%–3.0%) times years employed. This retirement benefit can be a "reasonably good" (75–85% of salary) retirement at close to the monthly salary they were last employed at. For example, if a person joined the University of California retirement system at age 25 and worked for 35 years they could receive 87.5% (2.5% × 35) of their average highest three year salary with full medical coverage at age 60. Police and firefighters who joined at 25 and worked for 30 years could receive 90% (3.0% × 30) of their average salary and full medical coverage at age 55. These retirements have cost of living adjustments (COLA) applied each year but are limited to a maximum average income of $350,000/year or less. Spousal survivor benefits are available at 100–67% of the primary benefits rate for 8.7% to 6.7% reduction in retirement benefits, respectively.[86] UCRP retirement and disability plan benefits are funded by contributions from both members and the university (typically 5% of salary each) and by the compounded investment earnings of the accumulated totals. These contributions and earnings are held in a trust fund that is invested. The retirement benefits are much more generous than Social Security but are believed to be actuarially sound. The main difference between state and local government sponsored retirement systems and Social Security is that the state and local retirement systems use compounded investments that are usually heavily weighted in the stock market securities—which historically have returned more than 7.0%/year on average despite some years with losses.[87] Short term federal government investments may be more secure but pay much lower average percentages. Nearly all other federal, state and local retirement systems work in a similar fashion with different benefit retirement ratios. Some plans are now combined with Social Security and are "piggy backed" on top of Social Security benefits. For example, the current Federal Employees Retirement System, which covers the vast majority of federal civil service employees hired after 1986, combines Social Security, a modest defined-benefit pension (1.1% per year of service) and the defined-contribution Thrift Savings Plan.

The current Social Security formula used in calculating the benefit level (primary insurance amount or PIA) is progressive vis-à-vis lower average salaries. Anyone who worked in OASDI covered employment and other retirement would be entitled to both the alternative non-OASDI pension and an Old Age retirement benefit from Social Security. Because of their limited time working in OASDI covered employment the sum of their covered salaries times inflation factor divided by 420 months yields a low adjusted indexed monthly salary over 35 years, AIME. The progressive nature of the PIA formula would in effect allow these workers to also get a slightly higher Social Security Benefit percentage on this low average salary. Congress passed in 1983 the Windfall Elimination Provision to minimize Social Security benefits for these recipients. The basic provision is that the first salary bracket, $0–791/month (2013) has its normal benefit percentage of 90% reduced to 40–90%—see Social Security for the exact percentage. The reduction is limited to roughly 50% of what you would be eligible for if you had always worked under OASDI taxes. The 90% benefit percentage factor is not reduced if you have 30 or more years of "substantial" earnings.[88]

The average Social Security payment of $1,230/month ($14,760/year) in 2013[89] is only slightly above the federal poverty level for one—$11,420/yr and below the poverty guideline of $15,500/yr for two.[90]

For this reason, financial advisers often encourage those who have the option to do so to supplement their Social Security contributions with private retirement plans. One "good" supplemental retirement plan option is an employer-sponsored 401(K) (or 403(B)) plan when they are offered by an employer. 58% of American workers have access to such plans.[91] Many of these employers will match a portion of an employee's savings dollar-for-dollar up to a certain percentage of the employee's salary. Even without employer matches, individual retirement accounts (IRAs) are portable, self-directed, tax-deferred retirement accounts that offer the potential to substantially increase retirement savings. Their limitations include: the financial literacy to tell a "good" investment account from a less advantageous one; the savings barrier faced by those who are in low-wage employment or burdened by debt; the requirement of self-discipline to allot from an early age the required percentage of salary into "good" investment account(s); and the self–discipline needed to leave it there to earn compound interest until needed after retirement. Financial advisers often suggest that long-term investment horizons should be used, as historically short-term investment losses "self correct", and most investments continue to deliver good average investment returns.[87] The IRS has tax penalties for withdrawals from IRAs, 401(K)s, etc. before the age of 59 1⁄2, and requires mandatory withdrawals once the retiree reaches 70; other restrictions may also apply on the amount of tax-deferred income one can put in the account(s).[92] For people who have access to them, self-directed retirement savings plans have the potential to match or even exceed the benefits earned by federal, state and local government retirement plans.

International agreements

People sometimes relocate from one country to another, either permanently or on a limited-time basis. This presents challenges to businesses, governments, and individuals seeking to ensure future benefits or having to deal with taxation authorities in multiple countries. To that end, the Social Security Administration has signed treaties, often referred to as Totalization Agreements, with other social insurance programs in various foreign countries.[93]

Overall, these agreements serve two main purposes. First, they eliminate dual Social Security taxation, the situation that occurs when a worker from one country works in another country and is required to pay Social Security taxes to both countries on the same earnings. Second, the agreements help fill gaps in benefit protection for workers who have divided their careers between the United States and another country.

The following countries have signed totalization agreements with the SSA (and the date the agreement became effective):[94]

- Italy (November 1, 1978)

- Germany (December 1, 1979)

- Switzerland (November 1, 1980)

- Belgium (July 1, 1984)

- Norway (July 1, 1984)

- Canada (August 1, 1984)

- United Kingdom (January 1, 1985)

- Sweden (January 1, 1987)

- Spain (April 1, 1988)

- France (July 1, 1988)

- Portugal (August 1, 1989)

- Netherlands (November 1, 1990)

- Austria (November 1, 1991)

- Finland (November 1, 1992)

- Ireland (September 1, 1993)

- Luxembourg (November 1, 1993)

- Greece (September 1, 1994)

- South Korea (April 1, 2001)

- Chile (December 1, 2001)

- Australia (October 1, 2002)

- Japan (October 1, 2005)

- Denmark (October 1, 2008)

- Czech Republic (January 1, 2009)

- Poland (March 1, 2009)

- Slovak Republic (May 1, 2014)

- Mexico (Signed on June 29, 2004, but not yet in effect)

Social Security number

A side effect of the Social Security program in the United States has been the near-universal adoption of the program's identification number, the Social Security number, as the de facto U.S. national identification number. The social security number, or SSN, is issued pursuant to section 205(c)(2) of the Social Security Act, codified as . The government originally stated that the SSN would not be a means of identification,[95] but currently a multitude of U.S. entities use the Social Security number as a personal identifier. These include government agencies such as the Internal Revenue Service, the military as well as private agencies such as banks, colleges and universities, health insurance companies, and employers.

Although the Social Security Act itself does not require a person to have a Social Security Number (SSN) to live and work in the United States,[96] the Internal Revenue Code does generally require the use of the social security number by individuals for federal tax purposes:

- The social security account number issued to an individual for purposes of section 205(c)(2)(A) of the Social Security Act shall, except as shall otherwise be specified under regulations of the Secretary [of the Treasury or his delegate], be used as the identifying number for such individual for purposes of this title.[97]

Importantly, most parents apply for Social Security numbers for their dependent children in order to[98] include them on their income tax returns as a dependent. Everyone filing a tax return, as taxpayer or spouse, must have a Social Security Number or Taxpayer Identification Number (TIN) since the IRS is unable to process returns or post payments for anyone without an SSN or TIN.

The Privacy Act of 1974 was in part intended to limit usage of the Social Security number as a means of identification. Paragraph (1) of subsection (a) of section 7 of the Privacy Act, an uncodified provision, states in part:

- (1) It shall be unlawful for any Federal, State or local government agency to deny to any individual any right, benefit, or privilege provided by law because of such individual's refusal to disclose his social security account number.

However, the Social Security Act provides:

- It is the policy of the United States that any State (or political subdivision thereof) may, in the administration of any tax, general public assistance, driver's license, or motor vehicle registration law within its jurisdiction, utilize the social security account numbers issued by the Commissioner of Social Security for the purpose of establishing the identification of individuals affected by such law, and may require any individual who is or appears to be so affected to furnish to such State (or political subdivision thereof) or any agency thereof having administrative responsibility for the law involved, the social security account number (or numbers, if he has more than one such number) issued to him by the Commissioner of Social Security.[99]

Further, paragraph (2) of subsection (a) of section 7 of the Privacy Act provides in part:

- (2) the provisions of paragraph (1) of this subsection shall not apply with respect to –

- (A) any disclosure which is required by Federal statute, or

- (B) the disclosure of a social security number to any Federal, State, or local agency maintaining a system of records in existence and operating before January 1, 1975, if such disclosure was required under statute or regulation adopted prior to such date to verify the identity of an individual.[100]

The exceptions under section 7 of the Privacy Act include the Internal Revenue Code requirement that social security numbers be used as taxpayer identification numbers for individuals.[101]

Demographic and revenue projections

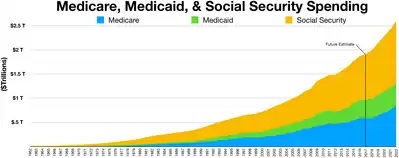

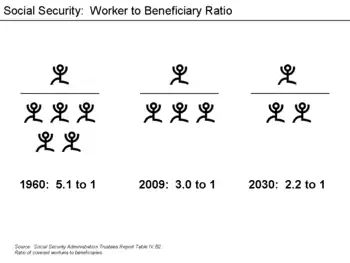

In each year since 1982, OASDI tax receipts, interest payments and other income have exceeded benefit payments and other expenditures, for example by more than $150 billion in 2004.[102] As the "baby boomers" move out of the work force and into retirement, however, expenses will come to exceed tax receipts and then, after several more years, will exceed all OASDI trust income, including interest. At that point the system will begin drawing on its trust fund Treasury Notes, and will continue to pay benefits at the current levels until the Trust Fund is exhausted. In 2013, the OASDI retirement insurance fund collected $731.1 billion and spent $645.5 billion; the disability program (DI) collected $109.1 billion and spent $140.3 billion; Medicare (HI) collected $243.0 and spent $266.8 billion and Supplementary Medical Insurance, SMI, collected $293.9 billion and spent $307.4 billion. In 2013 all Social Security programs except the retirement trust fund (OASDI) spent more than they brought in and relied on significant withdrawals from their respective trust funds to pay their bills. The retirement (OASDI) trust fund of $2,541 billion is expected to be emptied by 2033 by one estimate as new retirees become eligible to join. The disability (DI) trust fund's $153.9 billion will be exhausted by 2018; the Medicare (HI) trust fund of $244.2 billion will be exhausted by 2023 and the Supplemental Medical Insurance (SMI) trust fund will be exhausted by 2020 if the present rate of withdrawals continues—even sooner if they increase. The total "Social Security" expenditures in 2013 were $1,360 billion dollars, which was 8.4% of the $16,200 billion GNP (2013) and 37.0% of the federal expenditures of $3,684 billion (including a $971.0 billion deficit).[7][103] All other parts of the Social Security program: medicare (HI), disability (DI) and Supplemental Medical (SMI) trust funds are already drawing down their trust funds and are projected to go into deficit in about 2020 if the present rate of withdrawals continue.[104] As the trust funds are exhausted either benefits will have to be cut, fraud minimized or taxes increased. According to the Center for Economic and Policy Research, upward redistribution of income is responsible for about 43% of the projected Social Security shortfall over the next 75 years.[105]

In 2005, this exhaustion of the OASDI Trust Fund was projected to occur in 2041 by the Social Security Administration[106] or by 2052 by the Congressional Budget Office, CBO.[107] Thereafter, however, the projection for the exhaustion date of this event was moved up slightly after the recession worsened the U.S. economy's financial picture. The 2011 OASDI Trustees Report stated:

Annual cost exceeded non-interest income in 2010 and is projected to continue to be larger throughout the remainder of the 75-year valuation period. Nevertheless, from 2010 through 2022, total trust fund income, including interest income, is more than is necessary to cover costs, so trust fund assets will continue to grow during that time period. Beginning in 2023, trust fund assets will diminish until they become exhausted in 2036. Non-interest income is projected to be sufficient to support expenditures at a level of 77 percent of scheduled benefits after trust fund exhaustion in 2036, and then to decline to 74 percent of scheduled benefits in 2085.[108]

In 2007, the Social Security Trustees suggested that either the payroll tax could increase to 16.41 percent in 2041 and steadily increased to 17.60 percent in 2081 or a cut in benefits by 25 percent in 2041 and steadily increased to an overall cut of 30 percent in 2081.[109]

The Social Security Administration projects that the demographic situation will stabilize. The cash flow deficit in the Social Security system will have leveled off as a share of the economy. This projection has come into question. Some demographers argue that life expectancy will improve more than projected by the Social Security Trustees, a development that would make solvency worse. Some economists believe future productivity growth will be higher than the current projections by the Social Security Trustees. In this case, the Social Security shortfall would be smaller than currently projected.

Tables published by the government's National Center for Health Statistics show that life expectancy at birth was 47.3 years in 1900, rose to 68.2 by 1950 and reached 77.3 in 2002. The latest annual report of the Social Security Agency (SSA) trustees projects that life expectancy will increase just six years in the next seven decades, to 83 in 2075. A separate set of projections, by the Census Bureau, shows more rapid growth.[110] The Census Bureau projection is that the longer life spans projected for 2075 by the Social Security Administration will be reached in 2050. Other experts, however, think that the past gains in life expectancy cannot be repeated, and add that the adverse effect on the system's finances may be partly offset if health improvements or reduced retirement benefits induce people to stay in the workforce longer.

Actuarial science, of the kind used to project the future solvency of social security, is subject to uncertainty. The SSA actually makes three predictions: optimistic, midline, and pessimistic (until the late 1980s it made 4 projections). The Social Security crisis that was developing prior to the 1983 reforms resulted from midline projections that turned out to be too optimistic. It has been argued that the overly pessimistic projections of the mid to late 1990s were partly the result of the low economic growth (according to actuary David Langer) assumptions that resulted in pushing back the projected exhaustion date (from 2028 to 2042) with each successive Trustee's report. During the heavy-boom years of the 1990s, the midline projections were too pessimistic. Obviously, projecting out 75 years is a significant challenge and, as such, the actual situation might be much better or much worse than predicted.

The Social Security Advisory Board has on three occasions since 1999 appointed a Technical Advisory Panel to review the methods and assumptions used in the annual projections for the Social Security trust funds. The most recent report of the Technical Advisory Panel, released in June 2008 with a copyright date of October 2007, includes a number of recommendations for improving the Social Security projections.[111][112] As of December 2013, under current law, the Congressional Budget Office reported that the "Disability Insurance trust fund will be exhausted in fiscal year 2017 and the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance trust fund will be exhausted in 2033".[113] Costs of Social Security have already started to exceed income since 2018. This means the trust funds have already begun to be empty and will be fully depleted in the near future. As of 2018, the projections made by the Social Security Administration estimates that Social Security program as a whole will deplete all reserves by the year 2034.[114]

Increased spending for Social Security will occur at the same time as increases in Medicare, as a result of the aging of the baby boomers. One projection illustrates the relationship between the two programs:

From 2004 to 2030, the combined spending on Social Security and Medicare is expected to rise from 8% of national income (gross domestic product) to 13%. Two-thirds of the increase occurs in Medicare.[115]

Ways to eliminate the projected shortfall

Social Security is predicted to start running out of having enough money to pay all prospective retirees at today's benefit payouts by 2034.[114]

- Lift the payroll ceiling. The payroll ceiling is now adjusted for inflation.[116] Robert Reich, former United States Secretary of Labor, suggests lifting the ceiling on income subject to Social Security taxes, which is $127,200 as of January 1, 2017.[117]

- Increase Social Security taxes. If workers and employers each paid 7.6% (up from today's 6.2%), it would eliminate the financing gap altogether. This 1.4% increase (2.8% for self-employed) has over 60% support in surveys conducted by the National Academy of Social Insurance (NASI).[118]

- Raise the retirement age(s). Raising the early retirement option from age 62 to 64 would help to reduce Social Security benefit payouts.

- Means-test benefits. A phase out of Social Security benefits for those who already have income over $48,000/year ($4,000/month) would eliminate over 20% of the funding gap. This is not very popular, with only 31% of surveyed households favoring it.[118]

- Change the cost-of-living adjustment, COLA. Several proposals have been discussed. Effects of COLA reductions would be cumulative over time and would affect some groups more than others. Poverty rates would increase.[119]

- Reduce benefits for new retirees. If Social Security benefits were reduced by 3% to 5% for new retirees, about 18% to 30% percent of the funding gap would be eliminated.

- Average in more working years. Social Security benefits are now based on an average of a worker's 35 highest paid salaries with zeros averaged in if there are fewer than 35 years of covered wages. The averaging period could be increased to 38 or 40 years, which could potentially reduce the deficit by 10 to 20%, respectively.

- Require all newly hired people to join Social Security. Over 90% of all workers already pay FICA and SECA taxes, so there is not much to gain by this. There would be an early increase in Social Security income that would be partially offset later by the benefits they might collect when they retire.

Taxation

Tax on wages and self-employment income

Benefits are funded by taxes imposed on wages of employees and self-employed persons. As explained below, in the case of employment, the employer and employee are each responsible for one half of the Social Security tax, with the employee's half being withheld from the employee's pay check. In the case of self-employed persons (i.e., independent contractors), the self-employed person is responsible for the entire amount of Social Security tax.

The portion of taxes collected from the employee for Social Security are referred to as "trust fund taxes" and the employer is required to remit them to the government. These taxes take priority over everything, and represent the only debts of a corporation or LLC that can impose personal liability upon its officers or managers. A sole proprietor and officers of a corporation and managers of an LLC can be held personally liable for non-payment of the income tax and social security taxes whether or not actually collected from the employee.[120]

The Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) (codified in the Internal Revenue Code) imposes a Social Security withholding tax equal to 6.20% of the gross wage amount, up to but not exceeding the Social Security Wage Base ($97,500 for 2007; $102,000 for 2008; and $106,800 for 2009, 2010, and 2011). The same 6.20% tax is imposed on employers. For 2011 and 2012, the employee's contribution was reduced to 4.2%, while the employer's portion remained at 6.2%.[121][122] In 2012, the wage base increased to $110,100.[123] In 2013, the wage base increased to $113,700.[124] For each calendar year for which the worker is assessed the FICA contribution, the SSA credits those wages as that year's covered wages. The income cutoff is adjusted yearly for inflation and other factors.

A separate payroll tax of 1.45% of an employee's income is paid directly by the employer, and an additional 1.45% deducted from the employee's paycheck, yielding a total tax rate of 2.90%. There is no maximum limit on this portion of the tax. This portion of the tax is used to fund the Medicare program, which is primarily responsible for providing health benefits to retirees.

The Social Security tax rates from 1937–2010 can be accessed on the Social Security Administration's[125] website.

The combined tax rate of these two federal programs is 15.30% (7.65% paid by the employee and 7.65% paid by the employer). In 2011–2012 it temporarily dropped to 13.30% (5.65% paid by the employee and 7.65% paid by the employer).

For self-employed workers (who technically are not employees and are deemed not to be earning "wages" for federal tax purposes), the self-employment tax, imposed by the Self-Employment Contributions Act of 1954, codified as Chapter 2 of Subtitle A of the Internal Revenue Code, 26 U.S.C. §§ 1401–1403, is 15.3% of "net earnings from self-employment."[126] In essence, a self-employed individual pays both the employee and employer share of the tax, although half of the self-employment tax (the "employer share") is deductible when calculating the individual's federal income tax.[127][128]

If an employee has overpaid payroll taxes by having more than one job or switching jobs during the year, the excess taxes will be refunded when the employee files his federal income tax return. Any excess taxes paid by employers, however, are not refundable to the employers.

Wages not subject to tax

Workers are not required to pay Social Security taxes on wages from certain types of work:[129]

- A student working part-time for a university, enrolled at least half-time at the same university, and their relationship with the university is primarily an educational one.[130]

- A student who is a household employee for a college club, fraternity, or sorority, and is enrolled and regularly attending classes at a university.[131]

- A child under age 18 (or under age 21 for domestic service) who is employed by their parent.[132][133]

- A person who receives payments from a state or a local government for services performed to be relieved from unemployment.[134]

- An incarcerated person who works for the state or local government that operates the prison in which the person is incarcerated.[135][136][137]

- A person at an institution who works for the state of local government that operates the institution.[135][136]

- An employee of a state or local government who was hired on a temporary basis in response to a specific unforeseen fire, storm, snow, earthquake, flood, or a similar emergency, and the employee is not intended to become a permanent employee.[138][139]

- A newspaper carrier under age 18.[140]

- A real estate agent or salespeople's compensation if substantially all the compensation is directly related to sales or other output, rather than to the number of hours worked, and there is a written contract stating that the individual will not be treated as an employee for federal tax purposes.[141][142] The compensation is exempt if [141][142] * Employees of state or local government entities in Alaska, California, Colorado, Illinois, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Nevada, Ohio, and Texas.[143]

- Earnings as a council member of a federally recognized Indian tribe.[144][145]

- A fishing worker who is a member of a federally recognized Indian tribe that has recognized fishing rights.[146][145]

- A nonresident alien who is an employee of a foreign government on wages paid in their official capacities as foreign government employees.[147]

- A nonresident alien who is employed by a foreign employer as a crew member working on a foreign ship or foreign aircraft.[147][148]

- A nonresident alien who is a student, scholar, professor, teacher, trainee, researcher, physician, au pair, or summer camp worker and is temporarily in the United States in F-1, J-1, M-1, Q-1, or Q-2 nonimmigrant status for wages paid to them for services that are allowed by their visa status and are performed to carry out the purposes the visa status.[147]

- A nonresident alien who is an employee of an international organization on wages paid by the international organization.[147]

- A nonresident alien who is on an H-2A visa.[147]

- A nonresident alien who works in Guam, is a resident of the Philippines, and is on an H-2A, H-2B, or H-2R visa.[147]

- A member of certain religious groups, such as the Mennonites and the Amish, that consider insurance to be a lack of trust in God, and see it as their religious duty to provide for members who are sick, disabled, or elderly.[149][150][151]

- A person who is temporarily working outside their country of origin and is covered under a tax treaty between their country and the United States.[152]

- Net annual earnings from self-employment of less than $400.

- Wages received for service as an election worker, if less than $1,400 a year (in 2008).

- Wages received for working as a household employee, if less than $1,700 per year (in 2009–2010).

Federal income taxation of benefits

Originally the benefits received by retirees were not taxed as income. Beginning in tax year 1984, with the Reagan-era reforms to repair the system's projected insolvency, retirees with incomes over $25,000 (in the case of married persons filing separately who did not live with the spouse at any time during the year, and for persons filing as "single"), or with combined incomes over $32,000 (if married filing jointly) or, in certain cases, any income amount (if married filing separately from the spouse in a year in which the taxpayer lived with the spouse at any time) generally saw part of the retiree benefits subject to federal income tax.[153] In 1984, the portion of the benefits potentially subject to tax was 50%.[154] The Deficit Reduction Act of 1993 set the portion to 85%.

Criticisms

Claim of discrimination against the poor and the middle class

Workers must pay 12.4 percent, including a 6.2 percent employer contribution, on their wages below the Social Security Wage Base ($110,100 in 2012), but no tax on income in excess of this amount.[123][156] Therefore, high earners pay a lower percentage of their total income because of the income caps; because of this, and the fact there is no tax on unearned income, social security taxes are often viewed as being regressive. However, benefits are adjusted to be significantly more progressive, even when accounting for differences in life expectancy. According to the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office, for people in the bottom fifth of the earnings distribution, the ratio of benefits to taxes is almost three times as high as it is for those in the top fifth.[155]