Flagstaff War

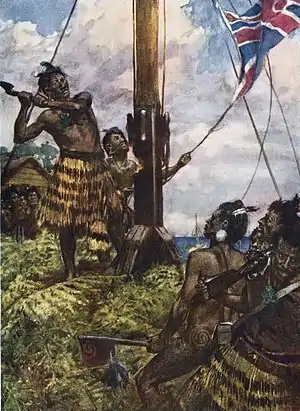

The Flagstaff War, also known as Heke's War, Hōne Heke's Rebellion and the Northern War, was fought between 11 March 1845 and 11 January 1846 in and around the Bay of Islands, New Zealand.[3] The conflict is best remembered for the actions of Hōne Heke who challenged the authority of the British by cutting down the flagstaff on Flagstaff Hill (Maiki Hill) at Kororāreka, now Russell. The flagstaff had been a gift from Hōne Heke to James Busby, the first British Resident. The Northern War involved many major actions, including the Battle of Kororāreka on 11 March 1845, the Battle of Ohaeawai on 23 June 1845 and the siege of Ruapekapeka Pā from 27 December 1845 to 11 January 1846.[4]

| Flagstaff War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the New Zealand Wars | |||||||

Hōne Heke removing the British ensign from Flagstaff Hill. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Māori allies | Māori | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Royal Navy: Captain Sir Everard Home, RN, HMS North Star; Acting-Commander David Robertson, RN, HMS Hazard; Lieutenant George Phillpotts, RN, HMS Hazard British Army: Lieutenant-Colonel William Hulme, 96th Regiment; Lieutenant Colonel Henry Despard, 99th Regiment Board of Ordnance: Captain William Biddlecomb Marlow, Commanding Royal Engineer Tāmati Wāka Nene |

Hōne Heke Te Ruki Kawiti Pūmuka | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Land: 58th Regiment ~ 10 officers and 200 men;[1] reinforced to 20 officers and 543 men[2] 99th Regiment ~ 7 officers and 150 men[1][2] Royal Engineers 1 Royal Marines ~ 2 officers and 80 men[2] Royal Navy ~ 33 officers and 280 seaman[2] Tāmati Wāka Nene ~ 450 warriors[2] Auckland Volunteer Militia ~ 42[2] Sea: sloop-of-war (HMS Hazard) corvette (HMS North Star) 28-gun sixth rate (HMS Calliope) 18-gun sloop (HMS Racehorse) 18-gun sloop HEICS Elphinstone 36-gun fifth-rate frigate (HMS Castor) |

Hōne Heke ~ 250–300 warriors Te Ruki Kawiti ~ 150–200 warriors | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

82 killed 164 wounded |

60–94 killed 80–148 wounded | ||||||

| Casualties of the Māori allied with the British are unknown. | |||||||

Causes

The signing of the Treaty of Waitangi started on 6 February 1840, and conflict between the Crown and Māori tribes was to some extent inevitable after that. Ostensibly, the treaty established the legal basis for the British presence in New Zealand. However, the actions of Hōne Heke and Te Ruki Kawiti in 1844 reflect the controversy that began soon after the treaty was signed. The meaning of the treaty remained at issue - and whether the Māori signatories intended to transfer sovereignty to the Crown or whether they understood the intention of the treaty as retaining the independence of the Māori people, while ceding to the Crown the authority over the matters described in the Maori version of the treaty. (Controversy continues into the 21st century: the Waitangi Tribunal, in Te Paparahi o te Raki inquiry (Wai 1040)[5][6] is engaged in the process of considering the Māori and Crown understandings both of the Declaration of Independence of 1835 and of the Treaty of Waitangi of 1840).

On 21 May 1840 William Hobson formally annexed New Zealand to the British Crown, and the following year he moved the capital from Russell to Auckland, some 200 kilometres (120 mi) south of Waitangi. In the Bay of Islands, Hōne Heke, one of the original signatories to the treaty, started to become increasingly unhappy with the outcome of the treaty. Among other things, Heke objected to the relocation of the capital to Auckland; moreover the Governor in Council imposed a custom tariff on staple articles of trade that resulted in a dramatic fall in the number of whaling ships that visited Kororāreka (over 20 whaling ships would visit the Bay of Islands at any one time);[4] a reduction in the number of visiting ships caused a serious loss of revenue to Ngāpuhi.[4] Heke and his cousin Tītore (c. 1775 - 1837) also collected and divided a levy of £5 on each ship entering the Bay.[4] Pōmare II complained that he no longer collected payment from American ships that called at Otuihu across from Opua.[7]

Heke and the Ngāpuhi chief Pōmare II had listened to Captain William Mayhew (the Acting-Consul for the United States from 1840) and other Americans talk about the successful revolt of the American colonies against England over the issue of taxation. Heke obtained an American ensign from Henry Green Smith, a storekeeper at Wahapu who had succeeded Mayhew as Acting-Consul. After the flagstaff was cut down for a second time, the Stars and Stripes flew from the carved sternpost of Heke's war canoe.[4]

Grievance of the Ngāpuhi

In the Bay of Islands, there existed a vague but widely diffused belief that the Treaty of Waitangi was merely a ruse of the Pākehā, and the belief that it was the intention of the Europeans, so soon as they became strong enough, to seize all Māori lands.[4][8] This belief, together with Heke's views about the imposition of the customs duties, can also be linked to the further widely diffused belief that the British flag flying on Flagstaff Hill over the town of Kororāreka signified that the Māori had become taurekareka (slaves) to Queen Victoria.[9][10] This discontent appears to have been fostered by the talk with the American traders, although it was an idea that had existed since the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi; William Colenso, the CMS missionary printer, in his record of the events of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi commented that "[a]fter some little time Te Kemara came towards the table and affixed his sign to the parchment, stating that the Roman Catholic bishop (who had left the meeting before any of the chiefs had signed) had told him "not to write on the paper, for if he did he would be made a slave."[11]

The trial and execution of Wiremu Kīngi Maketū in 1842 for murder was, in the opinion of Archdeacon Henry Williams, the beginning of Heke's antagonism towards the colonial administration, as Heke began gathering support thereafter among the Ngāpuhi for a rebellion.[12] However it was not until 1844 that Hōne Heke sought support from Te Ruki Kawiti and other leaders of the Ngāpuhi iwi by the conveying of 'te ngākau',[13] the custom observed by those who sought help to settle a tribal grievance.[14]

Hōne Heke moves against Kororāreka

Hōne Heke and Te Ruki Kawiti worked out the plan to draw the colonial forces into battle, with the opening provocations focusing on the flagstaff on Maiki Hill at the north end of Kororāreka (Russell).[14]

In July 1844, Kotiro, a former slave of Heke, openly insulted the Ngāpuhi chief. Kotiro had been captured from a southern tribe 15 years earlier, and was now living with her English husband, the town butcher, in Kororāreka. There are differing stories as to the specific insult or the circumstances in which it was delivered. Cowan (1922) describes Kotiro as while bathing with other women, during a heated argument about Heke, she dismissed him as an upoko poaka or a pig's head; and that upon hearing of this insult Heke used the insult as a reason to begin his attack on the town.[4] Carleton (1874) used the presence of Kotiro, and her status, as pretext for a taua – a raid upon Kororāreka.

It happened that a slave girl belonging to Heke, Kotiro by name, was living at Kororāreka with a butcher named Lord. Heke, having a colourable right to recover his slave. A karere [messenger] was sent ahead, to announce the intention; the message was delivered to the woman in the butcher's shop, where several fat hogs were hanging up. Kotiro answering contemptuously of their power to take her away, pointing to one of the hogs, said, ina a Heke [that is Heke]. In any event Heke used the insult as a reason to enter the town, to demand payment from Lord as compensation for the insult. Satisfaction was refused: for several days Heke and his warriors remained in the town persisting in the demand, but, in reality, feeling their way, trying the temper of the Pākehā.[15]

The Auckland Chronicle reported the incident as such:

[Heke and his warriors] brandished their tomohawks in the faces of the white people, indecently treated some white females, and exposed their persons; they took everything out of [Lord's, the husband of Kotiro] house.[15]

Flagstaff cut down for the first time

.jpg.webp)

On 8 July 1844 the flagstaff on Maiki Hill at the north end of Kororāreka was cut down for the first time, by the Pakaraka chief Te Haratua. Heke had set out to cut down the flagstaff, but was persuaded by Archdeacon William Williams not to do so.[15] The Auckland Chronicle reported this event, saying:

[They] then proceeded to the flagstaff, which they deliberately cut down, purposely with the intention of insulting the government, and of expressing their contempt of British authority.[16]

In the second week of August 1844, the barque Sydney arrived at the Bay of Islands from New South Wales with 160 officers and men of the 99th Regiment.[4] On 24 August 1844 Governor FitzRoy arrived in the bay from Auckland upon HMS Hazard.[17] The Government brig Victoria arrived in company with HMS Hazard, with a detachment of the 96th Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel William Hulme.[4] Governor FitzRoy summoned the Ngāpuhi chiefs to a conference at Te Waimate mission on 2 September and apparently defused the situation. Tāmati Wāka Nene requested the Governor to remove the troops and redress the native grievances in respect of the customs duties that were put in place in 1841, that Heke and Pōmare II viewed as damaging the maritime trade from which they benefited.[18] Tāmati Wāka Nene and the other Ngāpuhi chiefs undertook to keep Heke in check and to protect the Europeans in the Bay of Islands.[4] Hōne Heke did not attend, but sent a conciliatory letter and offered to replace the flagstaff.[4] The soldiers were returned to Sydney, but the accord did not last. The Ngāpuhi warriors led by Te Ruki Kawiti and Hōne Heke decided to challenge the Europeans at Kororāreka.

Flagstaff falls twice more

On 10 January 1845, the flagstaff was cut down a second time, this time by Heke. On 17 January, a small detachment of a subaltern and 30 men of the 96th Regiment were landed.[4] A new and stronger flagstaff sheathed in iron was erected on 18 January 1845 and the guard post built around it.[17] Nene and his men provided guards for the flagstaff,[17] but the next morning the flagstaff was felled for the third time.[4] Governor FitzRoy sent over to New South Wales for reinforcements.

Early in February 1845 Kawiti's warriors begun to plunder the settlers a mile or two from Kororāreka.[19] The Hazard arrived from Auckland on 15 February with the materials to construct the block-house around the base of the flagstaff. Within a few days the block-house was completed and a guard of 20 soldiers was placed in it.[4] Soon after this the officials purchased the mizzenmast from a foreign ship in the harbour and installed this as the fourth flagstaff.[20]

The British force consisted of about 60 soldiers of the 96th Regiment and about 90 Royal Marines and sailors from the Hazard,[19] plus colonists and sailors from the merchant ships provided about 200 armed men.[17]

Battle of Kororāreka

The next attack on the flagstaff on 11 March 1845 was a more serious affair. There were incidents between the Ngāpuhi warriors led by Hōne Heke, Kawiti and Kapotai on 7 and 8 March. A truce was declared for the next day, a Sunday, during which the Protestant Missionary Archdeacon Brown entered the camp of Heke and performed a service for him and his people. A Catholic priest conducted a service for those warriors among Kawiti's followers who were Christians.[19] Next day, Ngāpuhi warriors approached Kororāreka, but were fired upon. An account of the preparation for the attack later given by the CMS missionaries was that on Monday, the plans of Heke were disclosed to Gilbert Mair, who informed Police Magistrate Thomas Beckham,[4] who then informed Lieutenant George Phillpotts, RN, of HMS Hazard, but the "information was received with indifference, not unmingled with contempt".[19]

At dawn on Tuesday 11 March, a force of about 600 Māori armed with muskets, double-barrelled guns and tomahawks attacked Kororāreka.[19] Hōne Heke's men attacked the guard post, killing all the defenders and cutting down the flagstaff for the fourth time. At the same time, as a diversion, Te Ruki Kawiti and his men attacked the town of Kororāreka.[17] In the early afternoon, the powder magazine at Polack's Stockade exploded and surrounding buildings caught fire. The garrison of about 100 men managed to hold the perimeter while the town was evacuated to the ships moored in the bay.[17] Lieutenant Phillpotts of HMS Hazard ordered the bombardment of Kororāreka.[17] Europeans and Māori proceeded to plunder the buildings, and most of the buildings in the north of the town were burned. However, Heke had ordered that the southern end of the town, which included the missionaries' homes and the church, be left untouched.[17] Tāmati Wāka Nene and his men did not fight with the Ngāpuhi who sacked Kororāreka.[17] As the services of the Government Brig Victoria were no longer required, Thomas Beckham ordered her to sail for Auckland. Conveying the despatches and her share of the women and children, she departed at about 7.00 p.m.[21]

In the early hours of Thursday, 13 March, the third day, HMS Hazard prepared for sea. Lieutenant Phillpotts, RN, had deemed it advisable to sail with all despatch, considering that the flagstaff was down, the town sacked and burnt, and there was no further reason to remain. They had stayed as long as they could, and the sick and wounded required attention. At 8:30 am the flagstaff blockhouse was set alight, as well as the police office and temporary buildings on the beach. The refugees of Kororāreka sailed for Auckland, with HMS Hazard (whose sailors had taken part in the fighting ashore), the British whaler Matilda, schooner Dolphin and 21-gun United States corvette USS St. Louis departing the Bay of Islands throughout the day.

Thirteen soldiers and civilians had died in the battle or as a result of it soon after, with about 36 wounded. Heke and Kawiti were victorious and the Pākehā (Europeans) had been humbled.

Attack on the pā of Pōmare II

The British did not fight alone but had Māori allies, particularly Tāmati Wāka Nene and his men. He had given the government assurances of the good behaviour of the Ngāpuhi and he felt that Hōne Heke had betrayed his trust. Pōmare II remained neutral.[23]

The colonial government attempted to re-establish its authority in the Bay of Islands on 28 March 1845 with the arrival of troops, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel William Hulme, from the 58th, 96th and 99th Regiments with Royal Marines and a Congreve rocket unit.[24] The following day, the colonial forces attacked the pā (fortified village or community) of Pōmare II, notwithstanding his position of neutrality. The reason for the attack was what were claimed to be treasonous letters from Pōmare to Pōtatau Te Wherowhero that had been intercepted.[23]

As the pā was on the coast in the Bay of Islands, cannon fire from HMS North Star was directed at it. The colonial forces were able to occupy Pōmare's pā without a fight. When they arrived at the pā, Pōmare came down to see what all the fuss was about and was promptly made prisoner. He then ordered his men not to resist the British and they escaped into the surrounding bush. This left the British a free hand to loot and burn the pā. This action caused considerable puzzlement since up until that time, Pōmare had been considered neutral by himself and almost everyone else. When they burnt the pā, the British also burnt two pubs or grog shops which Pōmare had established within his pā to encourage the Pākehā settlers, sailors, whalers etc. to visit and trade with him. Pōmare was taken to Auckland on the North Star. He was released after the intervention of Tāmati Wāka Nene.[23]

Battle of the sticks

After the attack on Kororāreka Heke and Kawiti and the warriors travelled inland to Lake Omapere near to Kaikohe some 20 miles (32 km), or two days travel, from the Bay of Islands.[14] Tāmati Wāka Nene built a pā close to Lake Omapere. Heke's pā named Puketutu, was 2 miles (3.2 km) away, although it is sometimes named as "Te Mawhe" however the hill of that name is some distance to the north-east.[25] In April 1845, during the time that the colonial forces were gathering in the Bay of Islands, the warriors of Heke and Nene fought many skirmishes on the small hill named Taumata-Karamu that was between the two pās and on open country between Okaihau and Te Ahuahu.[26] Heke's force numbered about three hundred men; Kawiti joined Heke towards the end of April with another hundred and fifty warriors. Opposing Heke and Kawiti were about four hundred warriors that supported Tāmati Wāka Nene including his brother Eruera Maihi Patuone and the chiefs, Makoare Te Taonui and his son Aperahama Taonui, Mohi Tawhai, Arama Karaka Pi and Nōpera Panakareao.[27] F. E. Maning,[28] Jacky Marmon and John Webster, of Opononi, Hokianga were three Pākehā Māori (a European turned native) who volunteered to fight with Nene and fought alongside the warriors from Hokianga.[27] Webster used a rifle (a novel weapon at that time) and had made two hundred cartridges.[27]

Attack on Heke's pā at Puketutu

After the destruction of Pōmare II's pā, the 58th and 99th regiments moved to attack Heke's pā, choosing to travel by a walking track from the Bay of Islands rather than via a cart track that ran from Kerikeri through Waimate and passed nearby Heke's pā.[29] This decision may have been influenced by the wish of the missionaries to keep Te Waimate mission tapu by excluding armed men so as to preserve an attitude of strict neutrality.[26] In any event, this choice meant that cannon were not taken inland. After a difficult cross country march, they arrived at Puketutu Pā (Te Mawhe Pā) on 7 May 1845.

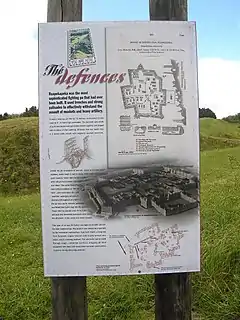

Because of the almost constant intertribal warfare, the art of defensive fortifications had reached a very high level among the Māori. A pā was usually situated on top of a hill, surrounded by palisades of timber that were backed up by trenches. Since the introduction of muskets the Māori had learnt to cover the outside of the palisades with layers of flax (Phormium tenax) leaves, making them effectively bulletproof as the velocity of musket balls was dissipated by the flax leaves.[30] For example, the pā at Ohaeawai, the site of a battle in the Flagstaff War, was described as having an inner palisade that was 3 metres (9.8 ft) high, built using Puriri logs. In front of the inner palisade was a ditch in which the warriors could shelter and reload their muskets, then fire through gaps in the two outer palisades.[31][32] The British were to discover, to their considerable cost, that a defended pā was a difficult fortification to defeat.

Lieutenant Colonel Hulme and his second-in-command, Major Cyprian Bridge, made an inspection of Heke's pā and found it to be quite formidable.[29] Lacking any better plan, they decided on a frontal assault the following day. The British troops had no heavy guns, but they had brought with them a dozen Congreve rockets. The Māori had never seen rockets used and were anticipating a formidable display. The first two missed their target completely; the third hit the palisade, exploded and was seen to have done no damage. This display gave considerable encouragement to the Māori. Soon all the rockets had been expended, leaving the palisade intact.[24]

The storming parties began to advance, first crossing a narrow gulley between Lake Omapere and the pā. Here they came under heavy fire both from the palisade and from the surrounding scrub. Kawiti and his warriors arrived and engaged the soldiers in the scrub and gullies around the pā.[29] It became apparent that there were as many warriors outside the pā as there were inside. There followed a savage and confused battle. Eventually the discipline and cohesiveness of the British soldiers began to prevail and the Māori were driven back inside their fortress. But they were by no means beaten, far from it. Without artillery, the British had no way to overcome the defences of the pā. Hulme decided to disengage and retreat back to the Bay of Islands.

At the Battle of Puketutu Pā (Te Mawhe Pā), the 58th and 99th regiments suffered casualties of 39 wounded and 13 dead; warriors of Heke and Kawiti were also killed.[33]

This battle is sometimes described as the Battle of Okaihau,[34] although Okaihau is 3 miles (4.8 km) to the west.[26]

Raid on Kapotai's pā

The return to the Bay of Islands was accomplished without incident. A week later, on 15 May, Major Bridge and three companies of troops and the warriors of Tāmati Wāka Nene attempted a surprise attack on Kapotai's pā on Waikare Inlet, which they could reach easily by sea. The defenders of the pā became aware of the attack and chose not to defend it, although the warriors of Kapotai and Nene fought in the forests around the pā.[35] The pā was soon burnt and destroyed.[24]

Lieutenant Colonel Hulme returned to Auckland and was replaced by Lieutenant Colonel Despard, a soldier who did very little to inspire any confidence in his troops.[24]

Battle of Te Ahuahu

Until the 1980s, histories of the First Māori War tend to ignore the poorly documented Battle of Te Ahuahu, yet it was in some ways the most desperate fight of the entire war. However, there are no detailed accounts of the action. It was fought entirely between the Māori: Hōne Heke and his tribe against Tāmati Wāka Nene and his warriors. As there was no British involvement in the action, there is limited mention of the event in contemporary British accounts.

After the successful defence of Puketutu pā on the shores of Lake Omapere, Hōne Heke returned to his pā at Te Ahuahu ("Heaped Up"), otherwise known as Puke-nui ("Big Hill"), a long-extinct volcano.[27] Te Ahuahu was a short distance from both Heke's pā at Puketutu and the site of the later Battle of Ohaeawai.[36] Some days later, he went to Kaikohe to gather food supplies. During his absence, one of Tāmati Wāka Nene's allies, the Hokianga chief, Makoare Te Taonui (the father of Aperahama Taonui), attacked and captured Te Ahuahu. This was a tremendous blow to Heke's mana or prestige; obviously it had to be recaptured as soon as possible.

The ensuing battle was a traditional formal Māori conflict, taking place in the open with preliminary challenges and responses. By Māori standards, the battle was quite large. Heke mustered somewhere between 400 and 500 warriors, while Tāmati Wāka Nene had about 300 men. Hōne Heke lost at least 30 warriors.[37] There are no detailed accounts of the battle fought on 12 June 1845 nearby Te Ahuahu at Pukenui.[24] Hugh Carleton (1874) provides a brief description of the battle: "Heke committed the error (against the advice of Pene Taui) of attacking Walker [Tāmati Wāka Nene], who had advanced to Pukenui. With four hundred men, he attacked about one hundred and fifty of Walker's party, taking them also by surprise; but was beaten back with loss. Kahakaha was killed, Haratua was shot through the lungs".[38]

Rev. Richard Davis also recorded that a "sharp battle was fought on the 12th inst. between the loyal and disaffected natives. The disaffected, although consisting of 500 men, were kept at bay all day, and ultimately driven off the field by the loyalists, although their force did not exceed 100. Three of our people fell, two on the side of the disaffected, and one on the side of the loyalists. When the bodies were brought home, as one of them was a principal chief of great note and bravery, he was laid in state, about a hundred yards from our fence, before he was buried. The troops were in the Bay at the time, and were sent for by Walker, the conquering chief; but they were so tardy in their movements that they did not arrive at the seat of war to commence operations until the 24th inst.!"[39][Note 1]

Tāmati Wāka Nene remained in control of Heke's pā.[37] Heke was severely wounded and did not rejoin the conflict until some months later, at the closing phase of the Battle of Ruapekapeka.[10][40] In a letter to Lieutenant Colonel Despard, Tāmati Wāka Nene described the battle as a "most complete victory over Heke".[41]

Battle of Ohaeawai

A debate occurred between Kawiti and the Ngatirangi chief Pene Taui as to the site of the next battle; Kawiti eventually agreed to the request to fortify Pene Taui's pā at Ohaeawai.[14]

Although it was now the middle of the southern winter, Lieutenant Colonel Despard insisted on resuming the campaign immediately with troops from the 58th and 99th Regiments, Royal Marines and a detachment of artillery they sailed across the bay to the mouth of the Kerikeri River and began to march inland to Ohaeawai, where Kawiti had built formidable defences around Pene Taui's pā;[32] the inner palisade, 3 metres (9.8 ft) high, was built using Puriri logs. In front of the inner palisade was a ditch in which the warriors could shelter and reload their muskets, then fire through gaps in the two outer palisades.[31] The conditions were atrocious: continual rain and wind on wet and sticky mud. It was several days before the entire expedition was gathered at the Waimate Mission, by which time Despard was apoplectic, so much so that when Tāmati Wāka Nene arrived with 250 men, Despard said that if he had wanted the assistance of savages, he would have asked for it. Fortunately, the interpreter delivered a completely different message.

The British troops arrived before the Ohaeawai pā on 23 June and established a camp about 500 metres (1,600 ft) away. On the summit of a nearby hill (Puketapu), they established a four-gun battery. They opened fire next day and continued until dark, but did very little damage to the palisade. The next day, the guns were brought to within 200 metres (660 ft) of the pā. The bombardment continued for another two days, but still caused very little damage. Partly this was due to the elasticity of the flax covering the palisade, but the main fault was a failure to concentrate the cannon fire on one area of the defences.

After two days of bombardment without effecting a breach, Despard ordered a frontal assault. He was, with difficulty, persuaded to postpone this pending the arrival of a 32-pound naval gun, which came the next day, 1 July. However an unexpected sortie from the pā resulted in the temporary occupation of the knoll on which Tāmati Wāka Nene had his camp and the capture of Nene's colours – the Union Jack. The Union Jack was carried into the pā. There it was hoisted, upside down, and at half-mast high, below the Māori flag, which was a Kākahu (Māori cloak).[1]

This insulting display of the Union Jack was the cause of the disaster which ensued.[14] Infuriated by the insult, Colonel Despard ordered an assault upon the pā the same day. The attack was directed at the section of the pā where the angle of the palisade allowed a double flank from which the defenders of the pā could fire at the attackers; the attack was a reckless endeavour.[42] The British persisted in their attempts to storm the unbreached palisades and five to seven minutes later 33 were dead and 66 injured.[33] The casualties included Captain Grant of the 58th Regiment and Lieutenant Phillpotts of HMS Hazard.[43]

Shaken by his losses, Despard decided to abandon the siege. However, his Māori allies opposed this. Tāmati Wāka Nene persuaded Despard to wait for a few more days. More ammunition and supplies were brought in and the shelling continued. On the morning of 8 July, the pā was found to have been abandoned, the enemy having disappeared in the night. When they had a chance to examine it, the British officers found it to be even stronger than they had feared.[44] It was duly destroyed, and the British retreated once again to the Bay of Islands. Te Ruki Kawiti and his warriors escaped, Hōne Heke recovered from his wounds, and a new and even stronger pā was built at Ruapekapeka.

The Battle of Ohaeawai was presented a victory for the British force, notwithstanding the death of about a third of the soldiers. The reality of the end of the Battle of Ohaeawai was that Te Ruki Kawiti and his warriors had abandoned the pā in a tactical withdrawal, with the Ngāpuhi moving on to build the Ruapekapeka pā from which to engage the British force on a battlefield chosen by Te Ruki Kawiti.

An account of the battle is provided by the Rev. Richard Davis, who was living at the CMS mission at Te Waimate mission and visited the pā during the siege; as a consequence, Despard complained as to interference by the missionary in the action against Hōne Heke.[45] The Rev. Richard Davis commented on the siege that, "[t]he, natives, I know, are capable of taking care of themselves. It was a happy thing for the troops, that they did not succeed in getting into the Pa. Had they accomplished their object, from the construction of the Pa the poor fellows must all have fallen. It was a sad sacrifice as it was of human life, and ought not to have been made. The Commander-in-chief had every opportunity of viewing the interior of the fort from the heights only about 500 yards distant. People's mouths were opened rather largely on the subject. The bravery of the poor fellows who made the attack was beyond all praise; but the wisdom of their commander has been questioned. To judge of this I leave to wiser heads than mine."[46]

Battle of Ruapekapeka

After the Battle of Ohaeawai, the troops remained at Waimate until the middle of October, destroying Te Haratua's pā at Pakaraka on 16 July 1845.[4][33] Te Ruki Kawiti and his allies, including Mataroria and Motiti,[14] constructed a pā at the place now known as Ruapekapeka, which was in a good defensive position, in an area of no strategic value, well away from non-combatants. The new governor, Sir George Grey, tried to make peace, but the Māori rebels wished to test the strength of their new pā against the British. A considerable force was assembled in the Bay of Islands. Between 7 and 11 December 1845, it moved up to the head of the Kawakawa River, one of the streams flowing into the Bay of Islands. They were then faced with 20 kilometres (12 mi) of very difficult country before they could reach Kawiti's new pā, Ruapekapeka or the Bat's Nest. This pā improved on the design used at the Ohaeawai pā. Lieutenant Balneavis, who took part in the siege described Ruapekapeka in his journal as "a model of engineering, with a treble stockade, and huts inside, these also fortified. A large embankment in rear of it, full of under-ground holes for the men to live in; communications with subterranean passages enfilading the ditch".[47]

The colonial forces, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Despard, consisted of the 58th Regiment (led by Lieutenant Colonel Wynward), the 99th Regiment (led by Captain Reed) and 42 volunteers from Auckland (led by Captain Atkyns). Tāmati Wāka Nene Patuone, Tawhai, Repa, and Nopera Pana-kareao led 450 warriors in support of the colonial forces.[2] The soldiers were supported by the Royal Marines (under Captain Langford) and sailors from HMS Castor, HMS Racehorse, HMS North Star,[2] HMS Calliope,[48] and the 18-gun sloop HEICS Elphinstone of the Honourable East India Company.[2]

The ordnance used in the battle were three naval 32-pounders, one 18-pounder, two 12-pounder howitzers, one 6-pounder brass gun, four 5½" brass Mann mortars,[49] and two Congreve rocket-tubes.[2] It took two weeks to bring the heavy guns into range of the pā. The cannon bombardment started on 27 December 1845. The directing officers were Lieutenant Bland (HMS Racehorse) and Lieutenant Leeds (HEICS Elphinstone); Lieutenant Egerton (HMS North Star) was in charge of firing the rocket-tubes.[2] The guns were fired with accuracy throughout the siege, causing considerable damage to the palisades, although those inside the pā were safe in the underground shelters.[2]

The siege continued for some two weeks, with enough patrols and probes from the pā to keep everyone alert. Then, early in the morning of Sunday, 11 January 1846, William Walker Turau, the brother of Eruera Maihi Patuone, discovered that the pā appeared to have been abandoned,[50] although Te Ruki Kawiti and a few of his warriors remained behind and appeared to have been caught unaware by the British assault.[51] The assaulting force drove Kawiti and his warriors out of the pā. Fighting took place behind the pā and most casualties occurred in this phase of the battle. The reason why the defenders appeared to have abandoned but then re-entered the pā is the subject of continuing debate. It was later suggested that most of the Māori had been at church, as many of them were devout Christians.[24] Knowing that their opponents, the British, were also Christians they had not expected an attack on a Sunday.[14][52] The Rev. Richard Davis noted in his diary of 14 January 1846, "Yesterday the news came that the Pa was taken on Sunday by the sailors, and that twelve Europeans were killed and thirty wounded. The native loss uncertain. It appears the natives did not expect fighting on the Sabbath, and were, the great part of them, out of the Pa, smoking and playing. It is also reported that the troops were assembling for service. The tars, having made a tolerable breach with their cannon on Saturday, took the opportunity of the careless position of the natives, and went into the Pa, but did not get possession without much hard fighting, hand to hand."[53]

However, later commentators cast doubt as to this explanation, as fighting did continue on Sunday at the Battle of Ohaeawai. Another explanation provided by later commentators is that Heke deliberately abandoned the pā to lay a trap in the surrounding bush, as this would provide cover and give Heke a considerable advantage.[54] If this is the correct explanation, then the Heke's ambush was only partially successful, as Kawiti's men, fearing their chief had fallen, returned towards the pā and the British forces engaged the Māori rebels immediately behind the pā.[55]

It was Māori custom that the place of a battle where blood was spilt became tapu, so the Ngāpuhi left the Ruapekapeka pā.[10][14] After the battle, Kawiti and his warriors, carrying their dead, travelled some 4 miles (6.4 km) north-west to Waiomio, the ancestral home of the Ngatihine.[51][56] The British forces, left in occupation of the pā, proclaimed a victory. Lieutenant Colonel Despard claimed the outcome as a "brilliant success".[57] The casualties in the British forces were in the 58th, 2 men killed; in the 99th, 1 man killed and 11 wounded; 2 marines killed and 10 wounded; and 9 seamen killed and 12 wounded.[2][33][57]

Later examination of the pā showed that it had been very well designed and very strongly built. Under different circumstances, it could have been a long and costly siege.[58] The earthworks can still be seen just south of Kawakawa. The ingenious design of the Ohaeawai pā and the Ruapekapeka pā became known to other Māori tribes.[59] These designs were the basis of what is now called the gunfighter pā that were built during the later New Zealand Wars.[60][61][62]

The Battle of Ruapekapeka Pā marked the end of the Flagstaff War. Kawiti and Heke did not suffer an outright defeat, but the war affected the Ngāpuhi – in the disruption to agriculture and in the presence of British forces who brought with them disease and social disruption.[63] While Kawiti expressed the will to continue to fight,[52] Kawiti and Heke made it known that they would end the rebellion if the colonial forces would leave Ngāpuhi land, and they asked Tāmati Wāka Nene to act as an intermediary in the negotiations with Governor Grey. The Governor accepted that clemency was the best way to ensure peace in the north. Heke and Kawiti were granted free pardons and none of their land was confiscated. This prompted Wāka to say to Grey, "you have saved us all."[51]

Just in time, as a new war was about to break out at the bottom end of the North Island, around Wellington.

The British casualties during the war were 82 killed and 164 wounded. Heke and Kawiti assessed their losses at 60 killed and 80 wounded, although the British estimated 94 killed and 148 wounded. There is no record of the numbers of allied Māori hurt during the conflict.

Outcome of the Flagstaff War

After the capture of Ruapekapeka, Kawiti and Heke approached Tāmati Wāka Nene about a ceasefire. This did not necessarily suggest they wished to acquiesce to British demands, but it did reflect the economic strain imposed on the Ngāpuhi and the disruption of food supplies and epidemics that resulted in significant numbers of deaths.[63] The war was, by Māori standards, unusually prolonged, and their casualties, whilst not crippling, were indeed serious.[64] Arguably, the British army, which was hardened to prolonged campaigns, may have had the resources to continue, had it not been for trouble brewing in the south.

The outcome of the Flagstaff War is therefore a matter of some debate. Although the war was widely lauded as a British victory,[57] it is clear that the outcome was somewhat more complex, even contentious.

To some extent, the objectives of the colonial government had been achieved: the war brought Kawiti and Heke's rebellion to an end.[51]

The capture of the Ruapekapeka pā can be considered a British tactical victory, but it was purpose-built as a target for the British, and its loss was not damaging; Heke and Kawiti managed to escape with their forces intact.[65]

It is clear that Kawiti and Heke made considerable gains from the war, despite the British victory at Ruapekapeka. After the war's conclusion, Heke enjoyed a considerable surge in prestige and authority. The missionary Richard Davis, writing in August 1848, stated that Heke had "raised himself to the very pinnacle of honour," and that "the whole of the tribes around pay him profound homage."[66]

The question of the ultimate result of the Northern War is contentious, as the British, Heke and Kawiti had all gained from its conclusion. For the British, their authority was preserved and the rebellion crushed, and their settlement of the area continued;[67] although the control exercised by the colonial government over the north was somewhat limited and exercised mainly through Tāmati Wāka Nene.[68] Heke and Kawiti both enjoyed increased prestige and authority amongst their peers.[66]

It is clear that both the British and their allies, as well as Hōne Heke and Te Ruki Kawiti, found the prospect of peace attractive, as the war took a considerable toll on both sides. Far from being a one-sided victory, in a military sense the Flagstaff War can be considered an inconclusive stalemate, as both sides wished the war to end, both gained somewhat from the fighting, and the situation more or less remained the same as it was before the outbreak of hostilities.[65] The political legacy of the rebellion by Kawiti and Heke was that during the time of Governor Grey and Governor Thomas Gore Browne, the colonial administrators were obliged to take account of the opinions of the Ngāpuhi before taking action in the Hokianga and Bay of Islands. The Waitangi Tribunal in The Te Roroa Report 1992 (Wai 38) state that "[a]fter the war in the north, government policy was to place a buffer zone of European settlement between Ngapuhi and Auckland."[69]

The flagstaff which had proved so controversial was not re-erected. Whilst the region was still nominally under British influence, the fact that the Government's flag was not re-erected was symbolically very significant. This was not lost on Henry Williams, who, writing to E.G. Marsh on 28 May 1846, stated that "the flag-staff in the Bay is still prostrate, and the natives here rule. These are humiliating facts to the proud Englishman, many of whom thought they could govern by a mere name."[66][70] The flagstaff that now stands at Kororāreka was erected in January 1858 at the direction of Kawiti's son Maihi Paraone Kawiti; the symbolism of the erection of the fifth flagstaff at Kororāreka by the Ngāpuhi warriors who had conducted the Flagstaff War, and not by government decree, indicates the colonial government did not want to risk any further confrontation with the Ngāpuhi.

Notes

- The comment by the Revd. Richard Davis that 'Three of our people fell' can be assumed to be a reference to Ngāpuhi that had been baptised as Christians by the CMS mission.

References

- Cowan, James (1922). "Chapter 8: The Storming-Party at Ohaeawai". The New Zealand Wars: a history of the Maori campaigns and the pioneering period, Volume I: 1845–1864. Wellington: R.E. Owen. pp. 60–72.

- Cowan, James (1922). "Chapter 9: The Capture of Rua-Pekapeka". The New Zealand Wars: a history of the Maori campaigns and the pioneering period, Volume I: 1845–1864. Wellington: R.E. Owen. pp. 73–87.

- Cowan, James (1955). "Scenes of Engagements, Bay of Islands District, 1845–46". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Volume I (1845–64). Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- Cowan, James (1922). "Volume I: 1845–1864". The New Zealand Wars: a history of the Maori campaigns and the pioneering period. Wellington: R.E. Owen. pp. 73–144.

- "Te Paparahi o Te Raki (Northland) inquiry – Waitangi Tribunal Report 2014: Volume 1" (PDF). Waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- "Te Paparahi o Te Raki (Northland) inquiry – Waitangi Tribunal Report 2014: Volume 2" (PDF). Waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- Kawiti, Tawai (October 1956). "Hekes War in the North". No. 16 Ao Hou, Te / The New World, National Library of New Zealand. p. 46. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- The Revd. William Williams (1847). Plain facts about the war in the north. Online publisher – State Library Victoria, Australia: Philip Kunst, Shortland Street, Auckland. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Carleton, Hugh (1874). "Vol. II". The Life of Henry Williams: "Early Recollections" written by Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. pp. 11–15.

- Carleton, Hugh (1874). Vol. II, The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. pp. 76–84.

- Colenso, William (1890). The Authentic and Genuine History of the Signing of the Treaty of Waitangi. Wellington: By Authority of George Didsbury, Government Printer. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- Carleton, Hugh (1874). "Vol. II". The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. pp. 35–43.

- "Māori Dictionary Online". John C Moorfield. 2005. Archived from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- Kawiti, Tawai (October 1956). "Hekes War in the North". No. 16 Ao Hou, Te / The New World, National Library of New Zealand. pp. 38–43. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- Carleton, Hugh, (1874) The Life of Henry Williams, Vol. II, pp. 81–82

- Moon, Paul and Biggs, Peter (2004) The Treaty and Its Times, Resource Books, Auckland

- "The sacking of Kororareka". Ministry for Culture and Heritage – NZ History online. 3 April 2009. Retrieved 16 September 2011.

- Cowan, James (1922). "Chapter 3: Heke and the Flagstaff". The New Zealand Wars: a history of the Maori campaigns and the pioneering period, Volume I: 1845–1864. Wellington: R.E. Owen. p. 19.

- Carleton, Hugh (1874). Appendix to Vol. II, The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library.

- New Zealand Electronic Text Centre The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Volume I (1845–64). Chapter 4: The fall of Korarareka.

- Log Book of the Government Brig Victoria, 1843 to 1845

- Roger, Blackley (1984). "Lance-Sergeant John Williams: Military Topographer of the Northern War". Art New Zealand no.32. pp. 50–53. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- Ballara, Angela (30 October 2012). "Pomare II". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- Raugh, Harold E. (2004). The Victorians at war, 1815–1914: an encyclopedia of British military history. ABC-CLIO. pp. 225–226. ISBN 978-1-57607-925-6.

- Cowan, James (1922). "Chapter 5: The First British March Inland". The New Zealand Wars: a history of the Maori campaigns and the pioneering period, Volume I: 1845–1864. Wellington: R.E. Owen. p. 42.

- Cowan, James (1922). "Chapter 5: The First British March Inland". The New Zealand Wars: a history of the Maori campaigns and the pioneering period, Volume I: 1845–1864. Wellington: R.E. Owen. p. 38.

- Cowan, James (1922). "Chapter 6: The Fighting at Omapere". The New Zealand Wars: a history of the Maori campaigns and the pioneering period, Volume I: 1845–1864. Wellington: R.E. Owen. p. 39.

- NZ Herald (13 November 1863)

- Reeves, William Pember (1895). "F. E. Maning "Heke's War … told by an Old Chief"". The New Zealand Reader. Samuel Costall, Wellington. pp. 173–179.

- Cowan, James (1955). "Flax-masked Palisade". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Volume I (1845–64). Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- Thomas Hutton, copied from a drawing taken by Mr Symonds of the 99th Regt. (1845). "Plan of Ohaeawai pa". New Zealand History Online. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- Carleton, Hugh (1874). Vol. II, The Life of Henry Williams – Letter of Mrs. Williams to Mrs. Heathcote, July 5, 1845. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. p. 115.

- King, Marie (1992). "A Most Noble Anchorage – The Story of Russell & The Bay of Islands". The Northland Publications Society, Inc., The Northlander No 14 (1974). Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- "Okaihau NZ Wars memorial cross – Inscription: A memorial / to the brave men who fell / in the assault on Heke's Pah / Okaihau, on May 8, 1845. / Erected by the N. Z. Govt. 1891". New Zealand History Online. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- Reeves, William Pember (1895). "F. E. Maning "Heke's War … told by an Old Chief"". The New Zealand Reader. Samuel Costall, Wellington. pp. 180–184.

- A. H. McLintock (1966). "HEKE POKAI, Hone". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- "Puketutu and Te Ahuahu – Northern War". Ministry for Culture and Heritage – NZ History online. 3 April 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- Carleton, H, (1874) The Life of Henry Williams, Vol. II. pp. 110–111. Thomas Walker was a name adopted by Tāmati Wāka Nene.

- Coleman, John Noble (1865). "IX". Memoir of the Rev. Richard Davis. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. p. 293.

- Rankin, Freda (1 September 2010). "Heke Pokai, Hone Wiremu". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- Belich, James (2013). "I – Te Ahuahu: The Forgotten Battle". The New Zealand Wars and the Victorian Interpretation of Racial Conflict. Auckland University Press.

- Carleton, Hugh (1874). Vol II, The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. p. 112.

- "New Zealand – Has the Work Died Out?". The Church Missionary Gleaner. 20: 115. 1870. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- "Chapter 8: The Storming-Party at Ohaeawai", The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period, James Cowan, 1955

- Coleman, John Noble (1865). "IX". Memoir of the Rev. Richard Davis. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. pp. 293–299.

- Coleman, John Noble (1865). "IX". Memoir of the Rev. Richard Davis. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. p. 303.

- Carleton, Hugh (1874). "Ruapekapeka, footnote 16, quoting journal of Lieutenant Balneavis". Vol. II, The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library.

- "HMS Calliope NZ Wars memorial". NZ History Online. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- Heath, Philip (Winter 2015). "Gother Mann's New Zealand Mountain Mortars". The Driving Wheel. No. 9. Auckland: MOTAT Society. pp. 23–32.

- Carleton, Hugh (1874). "Vol. I". The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. p. 243.

- Tim Ryan and Bill Parham (1986). The Colonial New Zealand Wars. Grantham House, Wellington NZ. pp. 27–28.

- Kawiti, Tawai (October 1956). "Hekes War in the North". No. 16 Ao Hou, Te / The New World, National Library of New Zealand. pp. 45–46. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- Coleman, John Noble (1865). "IX". Memoir of the Rev. Richard Davis. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. pp. 308–309.

- Tom Brooking (1988). Milestones – Turning Points in New Zealand History. Mills Publications. p. 69.

- Tim Ryan and Bill Parham, The Colonial New Zealand Wars, Grantham House, Wellington New Zealand (1986, reprinted with new material 2003) p. 27

- Kawiti, Tawai (October 1956). "Heke's War in the North". No. 16 Ao Hou, Te / The New World, National Library of New Zealand. p. 43. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- "Official Dispatches. Colonial Secretary's Office, Auckland, January 17, 1846". New Zealander, Volume 1, Issue 34. 24 January 1846. p. 4. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- Carleton, Hugh (1874). "Ruapekapeka". Vol. II, The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. pp. 121–127.

- "The Battle for Kawiti's Ohaeawai Pa", James Graham, HistoryOrb.com

- "The Modern Gun-Fighter's Pa (From notes supplied by the late Tuta Nihoniho)". New Zealand Electronic Text Collection. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- "Gunfighter pā, c1845". New Zealand history online. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- "Gunfighter Pa" (Tolaga Bay), Historic Places Trust website

- Rogers, Lawrence M. (1973). Te Wiremu: A Biography of Henry Williams. Pegasus Press. pp. 215–6.

- James Belich, The New Zealand Wars, p. 67

- Ian McGibbon, The Oxford Companion to New Zealand Military History, p. 373

- James Belich, The New Zealand Wars, p. 70

- Tim Ryan and Bill Parham, The Colonial New Zealand Wars, Grantham House, Wellington, New Zealand (1986, reprinted with new material 2003) p. 28

- James Belich, The New Zealand Wars, p. 66

- The Te Roroa Report 1992 (Wai 38), Waitangi Tribunal (1992) Chapter 1, Section 1.1. p. 8

- Carleton, Hugh (1874). Vol. II, The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. pp. 137–8.

Bibliography

- Barthorp, Michael (1979). To face the daring Māori. Hodder and Stoughton.

- Belich, James (1988). The New Zealand wars. Penguin.

- Tom Brooking (1988). Milestones – Turning Points in New Zealand History. Mills Publications.

- Carleton, Hugh (1874). Vol II, The Life of Henry Williams. Early New Zealand Books (ENZB), University of Auckland Library. p. 112.

- Cowan, James (1922). "Volume I: 1845–1864". The New Zealand Wars: a history of the Maori campaigns and the pioneering period. Wellington: R.E. Owen. pp. 73–144.

- Kawiti, Tawai (October 1956). Hekes War in the North. No. 16 Ao Hou, Te / The New World, National Library of New Zealand Library. pp. 38–46.

- Lee, Jack (1983). I have named it the Bay of Islands. Hodder and Stoughton.

- Lee, Jack (1987). Hokianga. Hodder and Stoughton.

- Tim Ryan and Bill Parham (2003). The Colonial New Zealand Wars. Grantham House, Wellington NZ.

- Simpson, Tony (1979). Te Riri Pakeha. Hodder and Stoughton.

- Vaggioli, Dom Felici (2000). History of New Zealand and its inhabitants, Trans. J. Crockett. Dunedin: University of Otago Press. Original Italian publication, 1896.

- Williams, The Revd. William (1847). Plain Facts relative to the Late War in the Northern District of New Zealand Online available from State Library of Victoria, Australia