Fur clothing

Fur clothing is clothing made of furry animal hides. Fur is one of the oldest forms of clothing, and is thought to have been widely used as hominids first expanded outside Africa. Some view fur as luxurious and warm; others reject it due to moral concerns for animal rights. The term 'fur' is often used to refer to a coat, wrap, or shawl made from the fur of animals. Controversy exists regarding the wearing of fur coats, due to animal cruelty concerns. The most popular kinds of fur in the 1960s (known as the luxury fur) were blond mink, silver striped fox and red fox. Cheaper alternatives were pelts of wolf, Persian lamb or muskrat. It was common for ladies to wear a matching hat. In the 1950s, a must-have type of fur was the mutation fur (naturally nuanced colours) and fur trimmings on a coat that were beaver, lamb fur, Astrakhan and mink.

_(cut).jpg.webp)

History

.jpg.webp)

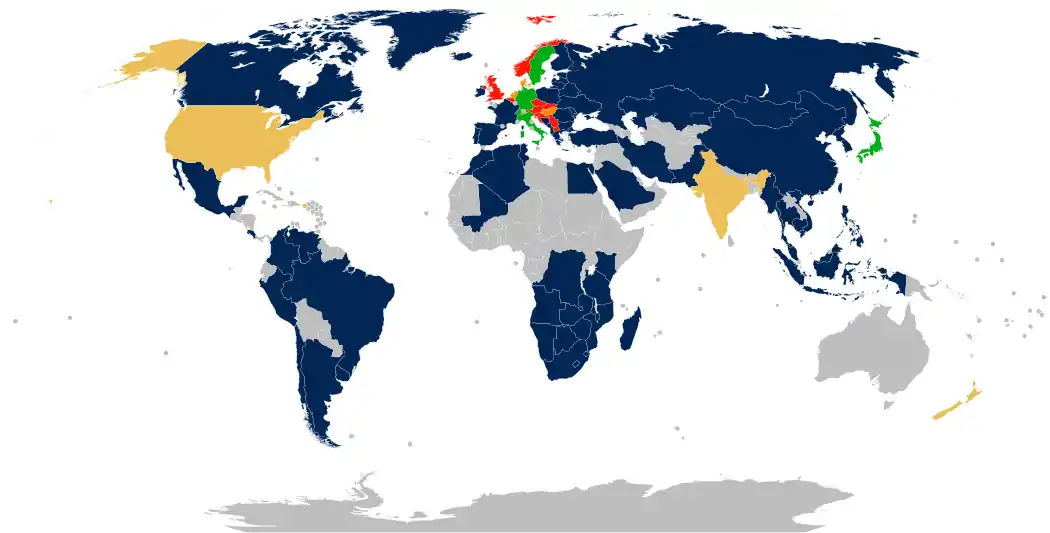

| | Killing animals for fur is illegal | | Killing animals for fur is partially illegal1 |

| | Killing animals for fur is legal, but importing or selling fur is illegal | | Killing animals for fur is legal, but strict anti-cruelty regulations make fur farms uneconomic |

| | Killing animals for fur is legal and active | | Unknown |

Fur is generally thought to have been among the first materials used for clothing and bodily decoration. The exact date when fur was first used in clothing is debated. It is known that several species of hominoids including Homo sapiens and Homo neanderthalensis used fur clothing.

Fur clothing predates written history and has been recovered from various archaeological sites worldwide. Crown proclamations known as "sumptuary legislation" were issued in England[1] limiting the wearing of certain furs to the higher social statuses, thereby establishing a cachet based on exclusivity. Furs such as marten, grey squirrel and ermine were reserved for the aristocracy, while fox, hare and beaver clothed the middle, and goat, wolf and sheepskin the lower. Fur was primarily used for visible linings, with species varied by season within social classes. Furbearing animals decreased in West Europe and began to be imported from the Middle East and Russia.[2]

As new kinds of fur entered Europe, other uses were made with fur other than clothing. Beaver was most desired but used to make hats which became a popular headpiece especially during wartime. Swedish soldiers wore broad-brimmed hats made exclusively from beaver felt. Due to the limitations of beaver fur, hat-makers relied heavily on North America for imports as beaver was only available in the Scandinavian peninsula.[2]

Other than the military, fur has been used for accessories such as hats, hoods, scarves, and muffs. Design elements including the visuals of the animal were considered acceptable with heads, tails and paws still being kept on the accessories. During the nineteenth century, Seal and karakul were made into indoor jackets. The twentieth century was the beginning of the fur coats being fashionable in West Europe with full fur coats. With lifestyle changes as a result of developments like indoor heating, the international textile trade affected how fur was distributed around the world. Europeans focused on using local resources giving fur association with femininity with the increasing use of mink. In 1970, Germany was the world's largest fur market. The International Fur Trade Federation banned endangering species furs like silk monkey, ocelot, leopard, tiger, and polar bear in 1975. The use of animal skins were brought to light during the 1980s by animal right organisations and the demand for fur decreased. Anti-fur organisations raised awareness of the controversy between animal welfare and fashion. Fur farming became banned in Britain in 1999. During the twenty-first century, fox and mink have been bred in captivity with Denmark, Holland and Finland being leaders of mink production.[1]

Fur is still worn in most mild and cool climates around the world due to its warmth and durability. From the days of early European settlement, up until the development of modern clothing alternatives, fur clothing was popular in Canada during the cold winters. The invention of inexpensive synthetic textiles for insulating clothing led to fur clothing falling out of fashion.

Fur is still used by indigenous people and developed societies, due to its availability and superior insulation properties. The Inuit peoples of the Arctic relied on fur for most of their clothing, and it also forms a part of traditional clothing in Russia, Ukraine, the former Yugoslavia, Scandinavia, and Japan.

It is also sometimes associated with glamour and lavish spending. A number of consumers and designers—notably British fashion designer and outspoken animal rights activist Stella McCartney—reject fur due to moral beliefs and cruelty to animals.[3]

Animal furs used in garments and trim may be dyed bright colors or with patterns, often to mimic exotic animal pelts: alternatively they may be left their original pattern and color. Fur may be shorn down to imitate the feel of velvet, creating a fabric called shearling.

Intro of alternatives in the early 20th century brought tension to clothing industry as the faux fur manufacturers started producing faux fur and capitalising on profits. By 1950s synthetic fur garments had become popular and affordable. Newspapers were writing articles on major chemical companies trying to outdo each other in the quest to create the most realistic fake fur.[4]

The popularity of natural fur has gone up and down in recent years. Vogue Paris published a homage to fur in August 2017 and later Gucci followed the idea of not using animal fur. Other high end brands to follow this lead are Stella McCartney, Givenchy, Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren, Michael Kors, Philosophy di Lorenzo Serafini. Burberry announced to stop sending models with fur on runways but did not stop selling it in stores. There are many companies coming up with more sustainable ways of producing leather and fur. Designer Ingar Helgason is developing Bio fur which would grows synthetic pelts the way that Modern Meadow has been able to produce grown leather and Diamond foundry created lab grown diamonds. BOF fur debate hosted by Zilberkweit director of the British Fur Association argued that natural fur was more sustainable. Others said that chemical processes needed to treat animals’ fur in order to be worn are just as detrimental to the environment.[5][6]

Heritage fashion houses such as Hermès, Dior and Chanel still use natural fur. Alex Mcintosh, who leads the Fashion Futures post grad program at London College of Fashion, says “Change on this level would only be driven on a genuine lack of demand and not just social media outcry”.[6]

Sources

Common animal sources for fur clothing and fur trimmed accessories include fox, rabbit, mink, raccoon dogs, muskrat, beaver, stoat (ermine), otter, sable, seals, cats, dogs, coyotes, wolves, chinchilla, opossum and common brushtail possum.[7] Some of these are more highly prized than others, and there are many grades and colors.

The import and sale of seal products was banned in the US in 1972 over conservation concerns about Canadian seals. The import and sale is still banned even though the Marine Animal Response Society estimates the harp seal population is thriving at approximately 8 million.[8] The import, export and sales of domesticated cat and dog fur were also banned in the US under the Dog and Cat Protection Act of 2000.[9]

Most of the fur sold by high fashion retailers globally is from farmed animals such as mink, foxes, and rabbits. Cruel methods of killing have made people more aware as the animal rights activists work harder to protect the animals. The recommendations (2001) of the European Commission's Scientific Committee on Animal Health and Animal Welfare (SCAHAW) state correspondingly: ‘In comparison with other farm animals, species farmed for their fur have been subjected to relatively little active selection except with respect to fur characteristics.[10][11]

Processing of fur

.jpg.webp)

The manufacturing of fur clothing involves obtaining animal pelts where the hair is left on. Depending on the type of fur and its purpose, some of the chemicals involved in fur processing may include table salts, alum salts, acids, soda ash, sawdust, cornstarch, lanolin, degreasers and, less commonly, bleaches, dyes and toners (for dyed fur).[12] Workers exposed to fur dust created during fur processing have been shown to have reduced pulmonary function in direct proportion to their length of exposure.[13]

The use of wool involves shearing the animal's fleece from the living animal, so that the wool can be regrown but sheepskin shearling is made by retaining the fleece to the leather and shearing it.[14] Shearling is used for boots, jackets and coats..

Leather made from any animal hide involves removing the fur from the skin and using only the tanned skin. The use of wool involves shearing the animal's hair from the living animal. Fake fur (or "faux fur") designates any synthetic material that attempts to mimic the appearance and feel of real fur.

The chemical treatment of fur to increase its felting quality is known as carroting, as the process tends to turn the tips of the fur orange. A furrier is a person who makes fur products such as fur garments, fur blankets etc. and repairs, alters, cleans, or otherwise deals in furs of animals.

The process of fur manufacturing includes waterways-pumping waste and the toxic chemicals in to the surrounding environment. On the other hand, fur is naturally biodegradable, whereas faux fur is not.[15]

Anti-fur campaigns

Anti-fur campaigns were popularized in the 1980s and 1990s, with the participation of numerous celebrities.[16] Fur clothing has become the focus of boycotts due to the opinion that it is cruel and unnecessary. PETA and other animal rights organizations, celebrities, and animal rights ethicists, have called attention to fur farming.

Animal rights advocates object to the trapping and killing of wildlife, and to the confinement and killing of animals on fur farms due to concerns about the animals suffering and death. They may also condemn "alternatives" made from synthetic (oil-based) clothing as they promote fur for the sake of fashion. Protests also include objection to the use of leather in clothing, shoes and accessories.

Some animal rights activists have disrupted fur fashion shows with protests, while other anti-fur protesters may use fashion shows featuring faux furs or other alternatives to fur clothing as a platform to highlight animal suffering from the use of real leathers and furs. These groups sponsor "Compassionate Fashion Day" on the third Saturday of August to promote their anti-fur message. Some American groups participate in "Fur Free Friday", an event held annually on the Friday after Thanksgiving (Black Friday) that uses displays, protests, and other methods to highlight their beliefs regarding furs.

In Canada, opposition to the annual seal hunt is viewed as an anti-fur issue, although the Humane Society of the United States claims that its opposition is to "the largest slaughter of marine mammals on Earth."[17] IFAW, an anti-sealing group, claims that Canada has an "abysmal record of enforcement" of anti-cruelty laws surrounding the hunt.[18] A Canadian government survey[19] indicated that two-thirds of Canadians supported the hunting of seals if the regulations under Canadian law.

PETA representative Johanna Fuoss credits social media and email marketing campaigns for helping to mobilize an unprecedented number of animal rights activists. “In the year before Michael Kors stopped using fur, he had received more than 150,000 emails,” Fuoss tells Highsnobiety. “This puts a certain pressure on designers who can see that the zeitgeist is moving away from fur. ”New technologies and platforms have made it easier than ever for those advocating change to get results. While in the past, activists had to invade runways with signs and paint, or physically mail privately viewed letters, today's activist can raise a commotion without leaving the house.[20][5][21]

The rise of social media has provided the general public with a direct line of communication to companies and a platform for opinions and protest, making it harder for brands to ignore targeted activism. “Brands are under huge pressure to respond to social media and avoid any controversy.” Says Mark Oaten, chief executive of the IFF.[22] The anti-fur messaging is being amplified by social media and a millennial customer base that is paying closer attention to the values represented by the products they buy.

The feeling of outrage against animal suffering is particularly intense when cats and dogs are involved, since these are the most popular pets in Western countries. Therefore, consumers demand to be assured about the production of furs, in order to avoid the risk of inadvertently buying products made with fur from these animals. To counteract the growing concern of consumers, European Union officially banned the import and export from all Member States of dog and cat furs, and all products containing fur from these species, with the Regulation 1523/2007,[23] applying since 31 December 2008. A combined method for species identification in furs, based on a combined morphological and molecular approach, has been proposed to discriminate dog and cat furs from allowed fur-bearing species, as this is a necessary step to comply with the ban.[24][25]

Fur trade

The fur trade is the worldwide buying and selling of fur for clothing and other purposes. The fur trade was one of the driving forces of exploration of North America and the Russian Far East.

Contemporary fashion industries

Today, fur is a popular material used by many fashion brands within the luxury sector, this includes high fashion labels Dior, Fendi, Oscar de la Renta and Louis Vuitton, as well as high street brands like Canada Goose and upcoming designers such as Saks Potts. In recent years, some brands and department stores have decided to ban fur and use alternative materials known as 'faux fur' or 'fake fur'. Reasons for this include ethical concerns and media awareness, with Burberry announcing they were banning fur after a highly publicised scandal about burning billions of dollars worth of excess stock was made public in 2018.[26]

See also

References

- "Savannah College of Art and Design". 0-www.bloomsburyfashioncentral.com.library.scad.edu. Retrieved 2017-11-05.

- "Savannah College of Art and Design". 0-www.bloomsburyfashioncentral.com.library.scad.edu. Retrieved 2017-11-05.

- "Fur-Free Designers and Retailers" Archived 2009-11-26 at the Wayback Machine July 31, 2009.

- Burberry Stops Destroying Product and Bans Real Fur. (2018, September 06). Retrieved from https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/professional/burberry-stops-destroying-product-and-bans-real-fur

- Op-Ed | Fashion's Fur-Free Future. (2018, August 11). Retrieved from https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/opinion/op-ed-fashions-fur-free-future

- Maisey, S. (2018, January 06). With more fashion brands declaring themselves fur free, what's next for the fur industry? . Retrieved from https://www.thenational.ae/lifestyle/with-more-fashion-brands-declaring-themselves-fur-free-what-s-next-for-the-fur-industry-1.693095

- "New Zealand turns a pest into luxury business". Taipeitimes.com. 2011-12-28. Retrieved 2012-01-04.

- "Harp Seal", Marine Animal Response Society.

- Rules and Regulations Under the Fur Products Labeling Act Archived 2008-07-24 at the Wayback Machine

- The environmental costs and health risks of fur. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.furfreealliance.com/environment-and-health/

- Fur bans. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.furfreealliance.com/fur-bans/

- Jos. H. Lowenstein & Sons Inc. "Fur Products". Jhlowenstein.com. Retrieved 2012-01-04.

- Chen, Jie; Lou, Jiezhi; Liu, Zhenlin (January 2003). "Pulmonary Function in Fur-Processing Workers: A Dose-Response Relationship". Archives of Environmental Health: An International Journal. 58 (1): 37–41. doi:10.3200/AEOH.58.1.37-41. PMID 12747517. S2CID 30463019. INIST:14777753.

- Australian Wool Corporation, Australian Wool Classing, Raw Wool Services, 1990.

- Hoskins, T. (2013, October 29). Is the fur trade sustainable? Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/sustainable-fashion-blog/is-fur-trade-sustainable

- "FICA sales stats". 18 March 2006. Archived from the original on 18 March 2006.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "Seal Hunt : The Humane Society of the United States". 16 June 2010. Archived from the original on 16 June 2010.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "Why commercial sealing is cruel". IFAW - International Fund for Animal Welfare.

- "Fisheries and Aquaculture Management - Seals and Sealing in Canada". 12 May 2008. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- Balmat, N. (2018, April 01). From vegan leather to bio fur: Growing materials from cells. Retrieved from https://futur404.com/growing-materials-cells/

- Waters, A. (2018, September 25). How Social Media is Pushing Fur Out of Fashion. Retrieved from https://www.highsnobiety.com/p/social-media-pushing-fur-out-fashion/

- Tamison., O. 2018. Why Fashion's Anti-Fur Movement is Winning. Business of Fashion. Retrieved from https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/intelligence/why-fashions-anti-fur-movement-is-winning

- European Parliament. 2007. Regulation (EC) No 1523/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2007 banning the placing on the market and the import to, or export from, the Community of cat and dog fur, and products containing such fur

- Mariacher A, Garofalo L, Fanelli R, Lorenzini R, Fico R. 2019. A combined morphological and molecular approach for hair identification to comply with the European ban on dog and cat fur trade. PeerJ 7:e7955. https://peerj.com/articles/7955/?td=wk

- Garofalo L, Mariacher A, Fanelli R, Fico R, Lorenzini R. 2018. Hindering the illegal trade in dog and cat furs through a DNA-based protocol for species identification. PeerJ 6:e4902 https://peerj.com/articles/4902/?td=wk

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-44885983

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fur garments. |

- Ernest Ingersoll (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.