Götz von Berlichingen

Gottfried "Götz" von Berlichingen (1480 – 23 July 1562), also known as Götz of the Iron Hand, was a German (Franconian) Imperial Knight (Reichsritter), mercenary, and poet. He was born around 1480 into the noble family of Berlichingen in modern-day Baden-Württemberg. Götz bought Hornberg Castle (Neckarzimmern) in 1517, and lived there until his death in 1562.[1]

He was active in numerous military campaigns during a period of 47 years from 1498 to 1544, including the German Peasants' War,[2] besides numerous feuds; in his autobiography he estimates that he fought 15 feuds in his own name, besides many cases where he lent assistance to his friends, including feuds against the cities of Cologne, Ulm, Augsburg and the Swabian League, as well as the bishop of Bamberg.

His name became famous as a euphemism for a vulgar expression (Er kann mich am Arsch lecken – "He can lick my ass") attributed to him by writer and poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), who wrote a play based on his life. (However, in the play it is written as "He can kiss my ass".) [3]

Life

In 1497, Berlichingen entered the service of Frederick I, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach. In 1498, he fought in the armies of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, seeing action in Burgundy, Lorraine, and the Brabant, and in the Swabian War the following year. By 1500, Berlichingen had left the service of Frederick of Brandenburg, and formed a company of mercenaries, selling his services to various Dukes, Margraves, and Barons.[4]

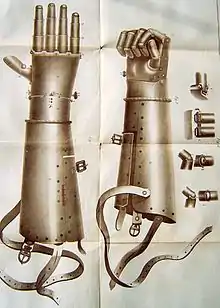

In 1504, Berlichingen and his mercenary army fought for Albert IV, Duke of Bavaria. During the siege of the city of Landshut, he lost his right arm at the wrist when enemy cannon fire forced his sword against him. He had two mechanical prosthetic iron replacements made. The first iron hand was a more simple device, claimed to have been made by a local blacksmith and a saddle maker. The second, more famous prosthetic hand was capable of holding objects from a shield or reins to a quill.[5] Both are on display today at the Burg Jagsthausen.[6] In spite of this injury, Berlichingen continued his military activities. In the subsequent years he was involved in numerous feuds, both of his own and in support of friends and employers.

In 1512, near the town of Forchheim, due to a long running and bitter feud with Nuremberg he raided a group of Nuremberg merchants returning from the great fair at Leipzig. On hearing this, Emperor Maximilian placed Berlichingen under an Imperial ban. He was only released from this in 1514, when he paid the large sum of 14,000 gulden. In 1516, in a feud with the Principality of Mainz and its Prince-Archbishop, Berlichingen and his company mounted a raid into Hesse, capturing Philip IV, Count of Waldeck, in the process. A ransom of 8,400 gulden was paid for the safe return of the count. For this action, he was again placed under an Imperial ban in 1518.[4]

In 1519, he signed up in the service of Ulrich, Duke of Württemberg, who was at war with the Swabian League. He fought in the defence of Möckmühl, but eventually was forced to surrender the town, owing to a lack of supplies and ammunition. In violation of the terms of surrender, he was held prisoner and handed over to the citizens of Heilbronn, a town he had raided several times. His fellow knights Georg von Frundsberg and Franz von Sickingen successfully argued for his release in 1522, but only after he paid a ransom of 2,000 gulden and swore not to take vengeance on the League.[4]

In 1525, with the outbreak of the German Peasants' War, Berlichingen led the rebel army in the district of Odenwald against the Ecclesiastical Princes of the Holy Roman Empire. Despite this, he was (according to his own account) not a fervent supporter of their cause. He agreed to lead the rebels partly because he had no other option, and partly in an effort to curb the excesses of the rebellion. Despite his wishes to stop wanton violence, Berlichingen found himself powerless to control the rebels and after a month of nominal leadership he deserted his command and returned to the Burg Jagsthausen to sit out the rest of the rebellion in his castle.[4]

After the Imperial victory, he was called before the Diet of Speyer to account for his actions. On 17 October 1526, he was acquitted by the Imperial chamber. Despite this, in November 1528 he was lured to Augsburg by the Swabian League, who were eager to settle old scores. After reaching Augsburg under promise of safe passage, and while preparing to clear himself of the old charges against him made by the league, he was seized and made prisoner until 1530 when he was liberated, but only after repeating his oath of 1522 and agreeing to return to his Burg Hornberg and remain in that area.[4]

Berlichingen agreed to this, and remained near the Hornberg until Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, released him from his oath in 1540. He served under Charles in the 1542 campaign against the Ottoman Empire of Suleyman the Magnificent in Hungary, and in 1544 in the Imperial invasion of France under Francis I of France.[4] After the French campaign, Berlichingen returned to the Hornberg and lived out the rest of his life in relative peace. He died on 23 July 1562 in Hornberg Castle at the age of 81 or 82. Berlichingen married twice and left three daughters and seven sons to carry on his family name.[4]

Legacy

Götz left an autobiography in manuscript form (Rossacher Handschrift). The text was published in 1731 as Lebens-Beschreibung des Herrn Gözens von Berlichingen ("Biography of Sir Götz von Berlichingen"), and republished in 1843 as Ritterliche Thaten Götz von Berlichingen's mit der eisernen Hand ("Knightly Deeds of Götz von Berlichingen with the Iron Hand") (ed. M. A. Gessert). A scholarly edition of the manuscript text was published in 1981 by Helgard Ulmschneider as Mein Fehd und Handlungen ("My Feuds and Actions").

Goethe in 1773 published the play Götz von Berlichingen based on the 1731 edition of the autobiography.

Jean-Paul Sartre's play Le Diable et le Bon Dieu features Götz as an existentialist character.

The Waffen-SS 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division Götz von Berlichingen in World War II was named after him.

The German submarine U-59 and U-70 each bore the emblem of a "War Glove" with the legend "Götz von Berlichingen!," while an emblem used by the U-69 pictured signal flags spelling out "L.M.A." --an initialism of the famed vulgar quote.

From commissioning in June 1958 until decommissioning in June 2006, the 2nd Fast Patrol Boat Squadron (2. Schnellbootgeschwader) of the German Navy used the clenched 'Iron Fist' of Götz von Berlichingen in the center of their squadron crest.

During World War II, one of the armed merchant cruisers sent by the Kriegsmarine to Japan was named Götz von Berlichingen by its captain after Kriegsmarine HQ rejected his initial suggestion Michael. The swap may refer to Berlichingen's famous imprecation: Er kann mich im Arsche lecken ("he can lick me in the arse").[7]

See also

References

- Adela (25 March 2017). "Götz of the Iron Hand". Naked History. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- Adela (25 March 2017). "Götz of the Iron Hand". Naked History. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- Morton, Ella (3 November 2015). "Object of Intrigue: the Prosthetic Iron Hand of a 16th-Century Knight". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- Chisholm 1911.

- Adela (25 March 2017). "Götz of the Iron Hand". Naked History. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- "Götzenburg (Baden-Württemberg) – Infos, News, Termine". www.burgen.de (in German). Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- "Norske forskere dømmer skibsfragt nord om Rusland ude | Ingeniøren". Ing.dk. Archived from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- Attribution

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Sources

- Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von – Götz von Berlichingen (1773).

- R. Pallmann – Der historische Götz von Berlichingen (Berlin, 1894).

- F. W. G. Graf von Berlichingen-Rossach – Geschichte des Ritters Götz von Berlichingen und seiner Familie (Leipzig, 1861).

- Lebens-Beschreibung des Herrn Gözens von Berlichingen – Götz's Autobiography, published Nürnberg 1731 (reprint Halle 1886).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Götz von Berlichingen. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1905 New International Encyclopedia article about "Götz von Berlichingen". |

- Title page of the 1731 edition of the memoirs of Götz von Berlichingen.

- 1886 edition at Googlebooks

- Mein Fehd und Handlungen German wikisource of 1567 ms of same.

- Further information about Götz's prosthetic arm

- Gatsos' poem "The Knight and Death" contains a reference to Götz and his arm.