Gaelic warfare

Gaelic warfare was the type of warfare practised by the Gaelic peoples, that is the Irish, Scottish, and Manx, in the pre-modern period.

Indigenous Gaelic Warfare

Weaponry

Irish warfare was for centuries centered on the Ceithearn, or kern in English (and so pronounced in Gaelic), light skirmishing infantry who harried the enemy with missiles before charging. John Dymmok, serving under Elizabeth I's lord-lieutenant of Ireland, described the kerns as:

"... A kind of footman, slightly armed with a sword, a target [round shield] of wood, or a bow and sheaf of arrows with barbed heads, or else three darts, which they cast with a wonderful facility and nearness..."[1]

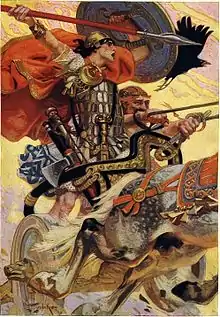

For centuries the backbone of Gaelic Irish warfare were lightly armed foot soldiers, armed with a sword (claideamh), long dagger (scian),[2] bow (bogha) and a set of javelins, or darts (ga).[3] The introduction of the heavy Norse-Gaelic Gallowglass mercenaries brought Longswords, similar to the Scottish claymore. Many of the medieval swords found in Ireland today are unlikely to be of native manufacture given many of the pommels and cross-guard decoration is not of Gaelic origin.[4] Gaelic warfare was anything but static, as Irish soldiers frequently looted or bought the newest and most effective weaponry. By the time of the Tudor reconquest of Ireland, the Irish had adopted Continental "pike and shot" formations, consisting of pikemen mixed with musketeers and swordsmen. Indeed, from 1593 to 1601, the Gaelic Irish fought with the most up-to-date methods of warfare, including full reliance on firearms (see Nine Years' War).[5]

Armour

For the most part, the Gaelic Irish fought without armour, instead wearing saffron coloured belted tunics called léine (pronounced 'laynuh'), the plural being léinte (pronounced 'layntuh/laynchuh'). Armour was usually a simple affair: the poorest might have worn padded coats; the wealthier might have worn boiled leather armour called cuir bouilli; and the wealthiest might have had access to bronze chest plates and perhaps mail (though it did exist in Ireland, it was rare). Gallowglass mercenaries have been depicted as having worn mail tunics and in latter period, steel burgonet helmets, but the majority of Gaelic warriors would have been protected only by a small shield. Shields were usually round, with a spindle shaped boss, though later the regular iron boss models were introduced by the Anglo-Saxons and Vikings. A few shields were also oval in shape or square, but most of them were small and round, like bucklers, to better enable agility.

Customs

In Gaelic Ireland, before the Viking age (when Vikings brought new forms of technology, culture and warfare into Ireland), there was a heavy importance placed on clan wars and ritual combat. Another very important aspect of Celtic ritual warfare at this time was single combat. To settle a dispute and measure one's prowess, it was customary to challenge an individual warrior from the other army to ritual single combat to the death while cheered on by the opposing hosts (see Champion warfare). Such fights were common before pitched battle, and for ritual purposes tended to occur at river fords.

Ritual Combat would later manifest itself in the Duel, as seen in the Scottish Martial Arts of the 18th century. The victor was determined by who made the first-cut. However, this was not always observed, and at times the duel would continue to the death.

Urban Defense

Many of the towns in the region had some type of defense in the form of walls or ditches. Within Gaelic Ireland many of the towns colonized by Anglo-Normans' often had defense walls due to the frontier type of lifestyle. Some had these walls built assuming that the town had no adequate defense with only using a ditch. The masonry walls on some towns had not been completed due to the economics of the time. While many of the towns often constructed what looks to be a defensive walls, this can sometimes not be the case. Towns constructed walls and town gates forensic times as a symbol of lordly wealth; physical expression of power, the defense of the walls and gates would become a secondary role.[6]

Tactics and organisation

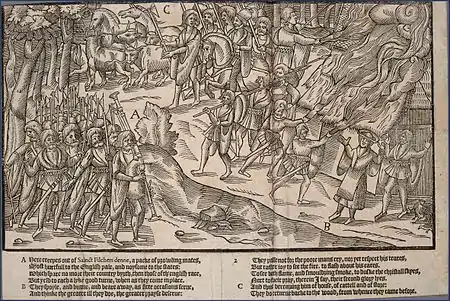

One of the most common causes of conflict in early Medieval Ireland was cattle raiding. Cattle were the main form of wealth in Gaelic Ireland, as it was in many parts of Europe, as currency had not yet been introduced, and the aim of most wars was the capture of the enemy's cattle. Indeed, cattle raiding had become a social institution, and newly crowned kings would carry out raids on traditional rivals. The Gaelic term creach rígh, or "king's raid", was used to describe the event, implying it was a customary tradition.[7] Initially ceithern were members of individual tribes, but later, when the Vikings and English introduced new systems of billeting to soldiers, the kern became billeted soldiers and mercenaries who served anyone who paid them the most. Because kerns were equipped and trained as light skirmishers, they faced a severe disadvantage in pitched battle. In battle, the kerns and lightly armed horsemen would charge the enemy line after intimidating them with war cries, horns and pipes.[8] If the kerns failed to break an enemy line after the charge, they were liable to flee. If the enemy formation did not break under the kern's charge, the heavily armed and armored Irish soldiers were used, they were later replaced in the late 13th century by the gallowglass who would advance from the rear and attack.

By the time of the Tudor reconquest of Ireland, the forces under Hugh O'Neill Earl of Tyrone adopted Continental pike-and-shot tactics to fight the invading English, however these formations proved vulnerable without adequate cavalry support. Firearms were widely used, often in ambush against enemy columns on the march.

Adaptations

As time went on, the Gaels began intensifying their raids and colonies in Roman Britain (c. 200–500 AD). Naval forces were necessary for this, and, as a result, large numbers of small boats, called currachs, were employed. Chariots and horses were transported across the sea to fight, but, because Gaelic forces were so frequently at sea (especially the Dál Riata Gaels), weaponry had to change. Javelins and slings became more uncommon, as they required too much space to launch, which the small currachs did not allow. Instead, more and more Gaels were armed with bows and arrows. The Dál Riata, for example, after colonising the west of Scotland and becoming a maritime power, became an army composed completely of archers. Slings also went out of use, replaced by both bows and a very effective naval weapon called the crann tabhaill, a kind of catapult. Later, the Gaels realised (probably learning from the Anglo-Saxons, whom they contacted in Britain), that the use of cavalry, as opposed to chariots, was cheaper, and by the 7th century AD, chariots had disappeared from Ireland and had been replaced by cavalry.

Later, when the Gaels came into contact with the Vikings, they realised the need for heavier weaponry, so as to make hacking through the much larger Norse shields and heavy mail-coats possible. Heavier hacking-swords became more frequent, as did helmets and mail-coats. The Gaels also learned how to use the double-handed "Dane Axe", wielded by the Vikings. Irish and Scottish infantry troops fighting with axes and armour, in addition to their own native darts and bows, were later known as Gall òglaigh (Gallowglass), or "foreign soldiers", and formed an important part of Gaelic armies in the future. The coming of the Normans into Ireland several hundred years later also forced the Irish to use an increasingly large number of more heavily armoured Gallowglasses and cavalry to effectively deal with the mail-clad Normans.

Standards and Music

Standards and hollowed out bull horns (a primitive battle trumpet) were often carried into battle to rally men into combat. Bagpipes would gain popularity in the later period notably the Great Highland Bagpipe and Great Irish Warpipes which would go on to be used by Gaelic mercenaries in Continental Europe and eventually develop into ceremonial instruments.

Exported Gaelic Warfare

Norse-Gaelic mercenaries

The most prolific Norse legacy in general Gaelic war though is the creation of the gall-òglaich (Scottish Gaelic) or gall-óglaigh (Irish), the Norse–Gaelic mercenaries who inhabited the Hebrides. They fought and trained in a combination of Gaelic and Norse techniques, and were highly valued; they were hired throughout the British Isles at different times, though most famously in Ireland. The French also often hired Irishmen and Scotsmen for their armies. Additionally, both the English and French hired Gaelic horsemen, called hobelars, the concepts of which were copied by both nations.

Later Weaponry

During the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, weapon imports from Europe influenced Gaelic weapon design. Take for example the German Zweihänder sword, a long double-handed weapon used for quick, powerful cuts and thrusts. Irish swords were copied from these models, which had unique furnishings. Many, for example, often featured open rings on the pommel. On any locally designed Irish sword in the Middle Ages, this meant you could see the end of the tang go through the pommel and cap the end. These swords were often of very fine construction and quality. Scottish swords continued to use the more traditional "V" cross-guards that had been on pre-Norse Gaelic swords, culminating in such pieces as the now famous "claymore" design. This was an outgrowth of numerous earlier designs, and has become a symbol of Scotland. The claymore was used together with the typical axes of the Gallowglasses until the 18th century, but began to be replaced by pistols and muskets. Also increasingly common at that time were basket-hilted swords, shorter versions of the claymore which were used with one hand in conjunction with a shield. These basket-hilted broadswords are still a symbol of Scotland to this day, as is the typical shield known as a "targe."

Notes

- Fergus Cannan, 'HAGS OF HELL': Late Medieval Irish Kern. History Ireland , Vol. 19, No. 1 (January/February 2011), pp. 14–17

- Sgian-dubh

- 'HAGS OF HELL': Late Medieval Irish Kern. History Ireland , Vol. 19, No. 1 (January/February 2011), pp. 17

- Halpin, Andrew (1986). "Irish Medieval Swords c. 1170-1600". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Section C: Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature. 86C: 183–230. JSTOR 25506140.

- G. A. Hayes-McCoy, "Strategy and Tactics in Irish Warfare, 1593–1601." Irish Historical Studies , Vol. 2, No. 7 (Mar. 1941), pp. 255

- McKeon, Jim (2011). "Urban Defences in Anglo-Norman Ireland: Evidence from South Connacht". Eolas: The Journal of the American Society of Irish Medieval Studies. 5: 146–190. JSTOR 41585270.

- Shae Clancy. "Cattle in Early Ireland". Celtic Well. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- Fergus Cannan, 'HAGS OF HELL': Late Medieval Irish Kern. History Ireland , Vol. 19, No. 1 (January/February 2011), pp. 17

References

- G. A. Hayes-McCoy, "Strategy and Tactics in Irish Warfare, 1593–1601". Irish Historical Studies, Vol. 2, No. 7 (Mar. 1941), pp. 255–279

- Fergus Cannan, "'HAGS OF HELL': late medieval Irish kern". History Ireland, Vol. 19, No. 1 (January/February 2011), pp. 14–17

- The Barbarians, Terry Jones

- Julius Caesar, "De Bello Gallico"

- "Tain Bo Cuailnge", From the Book of Leinster

- Geoffrey Keating, "History of Ireland"

- "The Wars of the Gaels with the Foreigners"

- http://www.myarmoury.com/feature_armies_irish.html

- http://www.myarmoury.com/feature_armies_scots.html