Gardez

Gardez (Pashto: ګردېز / Persian: گردیز; Gardēz, meaning "mountain fortress" in Middle Persian) is the capital of the Paktia Province of Afghanistan. The population of the city was estimated to be ca. 10,000 in the 1979 census and was estimated to be 70,000 in 2008.[1] The majority of the city's native population is Tajik. But recently, with the migration of Pashtun tribes from different parts of Paktia to this city, Pashtuns have taken over the majority of the population of this city.[1] The city of Gardez is located at the junction between two important roads that cut through a huge alpine valley. Surrounded by the mountains and deserts of the Hindu Kush, which boil up from the valley floor to the north, east and west, it is the axis of commerce for a huge area of eastern Afghanistan and has been a strategic location for armies throughout the country's long history of conflict. Observation posts built by Alexander the Great are still crumbling on the hilltops just outside the city limits.[3] The city of Gardez has a population of 70,641 (in 2015).[4] It has 13 districts and a total land area of 6,174 hectares (23.84 sq mi).[5] The total number of dwellings in this city is 7,849.[6]

Gardez

| |

|---|---|

City | |

The Bala Hesar fortress in the center of Gardez City | |

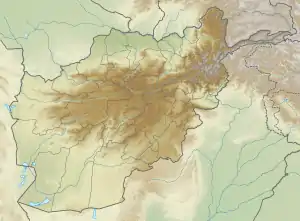

Gardez Location in Afghanistan | |

| Coordinates: 33°36′00″N 69°13′01″E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Paktia Province |

| District | Gardez District |

| Elevation | 2,308 m (7,572 ft) |

| Population (2008)[1] | |

| • City | 70,000 |

| • Urban | 70,641[2] |

| Time zone | UTC+4:30 (Afghanistan Standard Time) |

History

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Afghanistan |

|

| Timeline |

| Related historical names of the region |

|

Gardez is an ancient settlement, located within a large intramountainous depression in the Sulaiman Mountains of eastern Afghanistan.[8] Archaeological discoveries, including Greek, Sassanid, Hephthalite, and Hindu Shahi coins give an insight into the rich history of Gardez.

During 8th century, the Lawik rulers of the region adopted Islam. They formerly practiced either Hinduism or Buddhism, since they were associated with the Bhuddist-Kabul Shahis, and later with the Hindu Shahis (based in Gandhara, in present-day north-west Pakistan). Gardez later became a center of Kharijism and suffered several attacks by anti-Kharijite military chiefs. According to Zayn al-Akhbar, written by historian Abu Sa'id Gardezi, Abu Mansur Aflah Lawik was reduced to a tributary status in Gardez by Emir Ya'qub ibn al-Layth al-Saffar in 877.[9] However, the city remained under Lawik rule for about a century more. Around 975, Samanid-appointed governor Bilgetegin sieged Gardez but was killed by Lawiks during the attack. In 977, the Ghaznavids took Gardez, finally uprooting the Lawik dynasty. Some Lawiks, including Abu Sahal Marsal, entered the Ghaznavid nobility.[10] In 1162, the city fell to the Ghurid dynasty.

During the 16th-century, Gardez was renowned for its multi-storied houses—as mentioned by Babur in his Baburnama—and was the headquarter of the Mughal tūmān of "Zurmut", whose people were "Afghān-Shāl".[8][11]

Today, Gardez is the administrative center of a district of the Paktiā province, which covers 650 km2 and had a total population of 44,000 inhabitants in 1979, but was almost totally depopulated during the Soviet–Afghan War.

In 1960, the German government had their biggest rural development project with a budget of 2.5 million Deutsch Marks for the development of Paktiā ("Paktiā Development Authority", see above). The project was unsuccessful as the communist regime came to power in 1979. The communists lost control of most of Paktiā during the 1980s as the country plunged into war with only Gardez remaining in government control. In 2002, the city and surroundings was attacked by local warlord Pacha Khan Zadran, who was chosen as Paktia governor by Hamid Karzai's administration only to be refused by tribal elders.[12]

On 14 May 2020, a suicide truck bomber killed five civilians and injured at least 29 others near a court in Gardez. The Taliban claimed this as a revenge attack against the Afghan government, after President Ashraf Ghani blamed the group for the attack at a maternity hospital in Kabul two days earlier; the Taliban denied responsibility for the hospital attack.[13][14]

Location and infrastructure

Gardez is located at 2,308 m above sea level, making it the third-highest provincial capital in Afghanistan, and is not far from the Tora Bora region of caves and tunnels. The "old town", located at the foot of the Bālā Hesār fortress. The city is watered by the upper course of the Gardez River, which flows into the Ab-i Istada lake. Gardez is located at a junction between two important roads, one connecting Kabul with Khost, the other linking Ghazni with Parachinar in Pakistan's Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Gardez is 70 kilometres (43 mi) northwest of Khost and 100 kilometres (62 mi) south of Kabul.

Climate

Gardez has a cold semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSk) with dry summers and cold, snowy winters. Precipitation is low, and mostly falls in winter and spring.

| Climate data for Gardez | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14.6 (58.3) |

12.7 (54.9) |

24.7 (76.5) |

26.5 (79.7) |

31.0 (87.8) |

34.5 (94.1) |

34.8 (94.6) |

33.8 (92.8) |

30.0 (86.0) |

27.8 (82.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

17.6 (63.7) |

34.8 (94.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 1.0 (33.8) |

2.3 (36.1) |

8.8 (47.8) |

16.8 (62.2) |

22.2 (72.0) |

27.8 (82.0) |

29.6 (85.3) |

29.0 (84.2) |

25.1 (77.2) |

18.6 (65.5) |

11.9 (53.4) |

5.7 (42.3) |

16.6 (61.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −6.1 (21.0) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

2.7 (36.9) |

10.1 (50.2) |

15.1 (59.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.1 (70.0) |

16.7 (62.1) |

10.5 (50.9) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

9.1 (48.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −11.7 (10.9) |

−10.1 (13.8) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

4.0 (39.2) |

7.9 (46.2) |

12.5 (54.5) |

14.9 (58.8) |

13.8 (56.8) |

8.4 (47.1) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

2.4 (36.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −31 (−24) |

−30.0 (−22.0) |

−19.6 (−3.3) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

4.7 (40.5) |

9.0 (48.2) |

4.5 (40.1) |

0.5 (32.9) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

−13.2 (8.2) |

−27.8 (−18.0) |

−31 (−24) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 35.8 (1.41) |

61.7 (2.43) |

65.5 (2.58) |

50.4 (1.98) |

21.7 (0.85) |

4.8 (0.19) |

15.8 (0.62) |

7.5 (0.30) |

0.9 (0.04) |

5.8 (0.23) |

12.4 (0.49) |

33.2 (1.31) |

315.5 (12.43) |

| Average rainy days | 1 | 1 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 36 |

| Average snowy days | 8 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 29 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69 | 72 | 66 | 58 | 47 | 39 | 49 | 51 | 45 | 45 | 51 | 60 | 54 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 171.5 | 166.8 | 214.2 | 242.9 | 316.2 | 357.5 | 343.0 | 335.8 | 329.8 | 302.4 | 253.9 | 200.4 | 3,234.4 |

| Source: NOAA (1970-1983) [15] | |||||||||||||

Land use

Gardez is located in eastern Afghanistan close to Ghazni and Khost.[5] Gardez is predominately non-built up area with agriculture as the largest land use at 39%.[5] Residential area accounts for almost half of built-up area and Districts 1-4 consist of the densest housing.[5]

Demographics

As of 2008, the population of Gardez was estimated to be around 73,131. Pashtuns make up ca. 70% of the population while the Tajik community accounts for ca. 30%.[16]

The Encyclopaedia Iranica states that the population of the city was 9,550 in 1979 and that "They were mainly Fārsīwān Tājīks, Gardīz belonging to a network of old isolated Tājīk settlements sparsely distributed in southeastern Afghanistan that are remnants of a time when Pashto had not yet reached the area. There was also a significant community of Hindu and Sikh shopkeepers who altogether ran 9% of the shops in the bāzār, mostly specializing in jewellery and cloth"[8]

Gardez has also a huge Sayed population. However, this population is not counted by statistics. A lot of Gardezi Sayeds have immigrated to Pakistan and India (Gardēzī Sadaat).

Economy and administration

The city of Gardez is also a major fuel wood market for Kabul. Many of its natural forests are being cut down to provide fuel wood especially during winter.

During the 1970s, Gardez experienced an economic boom as a result of the German-funded "Paktiā Development Authority", established in 1965, and of the asphalting of the road to Kabul. Social services included three schools for boys, one school for girls, a hospital, one teacher training institute, the Madrasaye Roshānī, two hotels, and forty mosques. Most of these buildings were destroyed during the civil war in the 1980s.

After the fall of the Taliban, the first Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) in Afghanistan was established in Paktiā near Gardez in early March 2003, headed by the US Army along with a U.S. Agency for International Development representative, Randolph Hampton. There are now over 30 PRTs in Afghanistan. The continuing challenge to bring electricity, medical clinics, schools and water to the more remote villages in Paktia are a result of ongoing security issues.

Security and politics

Gardez was the former home of the 3rd Corps of the Afghan Army. By the Afghan Militia Forces period (c.2002), the corps 'theoretically incorporated 14th Division, 30th Division, 822nd Brigade, Border Brigades, and approximately 800... in the Governor's Force in Paktya, Ghazni, Paktika, and Khost Provinces.[17] The corps was disbanded around 2003-2005 and replaced in the new Afghan National Army by the 203rd Corps.

According to local Police Chief Brigadier General Aziz Ahmad Wardak, six people were arrested on 19 August 2009 for distributing night letters threatening people with attacks if they participated in the election.[18]

Notable people from Gardez

- Abu Sa'id Gardezi, 11th-century geographer and historian

- Shah Gardez, 11th-century Sufi saint who established himself in Multan, India (now in Pakistan)

- Mohammad Najibullah, President of Afghanistan from 1987 to 1992

- Khalaf ibn Ahmad, the last Saffarid Emir who died in Gardez in 1009 where he had been sent after the Ghaznavid conquest

See also

References and notes

- Pike, John. "Gardez". Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- "The State of Afghan Cities report 2015". Archived from the original on 2015-10-31.

- Scar, Ken (February 22, 2012). "AUP takes the reins from US soldiers in Gardez". U.S. Central Command. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved August 1, 2015.

- "The State of Afghan Cities report2015". Archived from the original on 2015-10-31.

- "The State of Afghan Cities report 2015". Archived from the original on 2015-10-31. Retrieved 2015-10-22.

- "The State of Afghan Cities report2015". Archived from the original on 2015-10-31. Retrieved 2015-10-22.

- Balogh, Dániel. Hunnic Peoples in Central and South Asia: Sources for their Origin and History. Barkhuis. p. 106. ISBN 978-94-93194-01-4.

- Daniel Balland, "GARDĪZ", in Encyclopaedia Iranica (Online Edition, (LINK)

- Clifford Edmund Bosworth (1977). The Medieval History of Iran, Afghanistan, and Central Asia. Variorum Reprints. pp. 302–303.

- "Hodūd al-Ālam", ed. Sotūda, p. 71, tr. Minorsky, p. 91; Bivar & Bosworth, 1965, pp. 17 ff.

- Beveridge, Annette Susannah (7 January 2014). The Bābur-nāma in English, Memoirs of Bābur. Project Gutenberg.

- HOLGUIN, JAIME. "Afghan Warlord Defiant Amid Threats". www.cbsnews.com.

- "Official Says Suicide Attack in Eastern Afghanistan Kills 5". Associated Press. May 14, 2020 – via NYTimes.com.

- "Truck bomb in eastern Afghan city kills five, Taliban claim responsibility". Reuters. May 14, 2020 – via www.reuters.com.

- "Gardiz Climate Normals 1961-1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-04. Retrieved 2011-12-16.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Michael Bhatia, Mark Sedra, Michael Vinay Bhatia, Mark Sedra, 'Afghanistan, Arms and Conflict: Post-9/11 Security and Insurgency, Routledge, 2008, ISBN 113405422X, 209.

- Niazai, Lemar (19 August 2009). "10 detained for distributing night letters". PAJHWOK ELECTIONS.

Literature

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gardez. |

- S. Radojicic, Report on Hydrogeological Survey of Paktya Province, Kabul, UNICEF, 1977

- C.E. Bosworth, "Notes on the Pre-Ghaznavid History of Eastern Afghanistan", in The Islamic Quarterly IX, 1965