Genevieve

Genevieve (French: Sainte Geneviève; Latin: Sancta Genovefa, Genoveva; from Gaullish geno "race, lineage" and uida "sage")[1] (Nanterre, c. 419/422 AD – Paris 502/512 AD), is the patron saint of Paris in the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox traditions. Her feast day is kept on 3 January.

Saint Genevieve | |

|---|---|

Saint Genevieve, seventeenth-century painting, Musée Carnavalet, Paris | |

| Born | c. 419–422 Nanterre, Western Roman Empire |

| Died | 502–512 (aged 79–93) Paris, Francia |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Canonized | Pre-congregation |

| Feast | 3 January |

| Attributes | a candle |

| Patronage | Paris |

She was born in Nanterre and moved to Paris (then known as Lutetia) after encountering Germanus of Auxerre and Lupus of Troyes and dedicated herself to a Christian life.[2] In 451 she led a "prayer marathon"[3] that was said to have saved Paris by diverting Attila's Huns away from the city. When the Germanic king Childeric I besieged the city in 464, she acted as an intermediary between the city and its besiegers, collecting food and convincing Childeric to release his prisoners.[2]

Her following and her status as patron saint of Paris were promoted by Clotilde, who may have commissioned the writing of her vita. This was most likely written in Tours, where Clotilde retired after her husband's death, as evidenced also by the importance of Martin of Tours as a saintly model.[2]

Life

Though there is a vita that purports to be written by a contemporary, Genevieve's history cannot be separated from her hagiography. She was described as a peasant girl born in Nanterre to Severus (a Gallo-Roman) and Geroncia (Greek origins). On his way to Britain, Germanus of Auxerre stopped at Nanterre, and Genevieve confided to him that she wanted to live only for God. He encouraged her and at the age of fifteen, Genevieve became a nun. On the deaths of her parents, she went to live with her godmother Lutetia in Paris ("Lutetia" was the former name of the city of Paris, so this has symbolic weight). There the young woman became admired for her piety and devotion to works of charity, and practiced corporal austerities which included abstaining from meat and breaking her fast only twice in the week. "These mortifications she continued for over thirty years, till her ecclesiastical superiors thought it their duty to make her diminish her austerities."[4] She encountered opposition and criticism for her activities, both before and after she was again visited by Germanus from those who were jealous or considered her an impostor or hypocrite.

Genevieve had frequent visions of heavenly saints and angels. She reported her visions and prophecies, until her enemies conspired to drown her in a lake. Through the intervention of Germanus, their animosity was finally overcome. The Bishop of Paris appointed her to look after the welfare of the virgins dedicated to God, and by her instruction and example she led them to a high degree of sanctity.[4]

Shortly before the attack of the Huns under Attila in 451 on Paris, Genevieve and Germanus' archdeacon persuaded the panic-stricken people of Paris not to flee but to pray. It is claimed that the intercession of Genevieve's prayers caused Attila's army to go to Orléans instead.[5] During Childeric's siege and blockade of Paris in 464, Genevieve passed through the siege lines in a boat to Troyes, bringing grain to the city. She also pleaded to Childeric for the welfare of prisoners-of-war, and met with a favorable response. Through her influence, Childeric and Clovis displayed unwonted clemency towards the citizens.[4]

Genevieve cherished a particular devotion to Saint Denis, and wished to erect a chapel in his honor to house his relics. Around 475 Genevieve purchased some land at the site of his burial and exhorted the neighboring priests to use their utmost endeavors. When they replied that they had no lime, she sent them to the bridge of Paris, where they learned the whereabouts of large quantities of this material from the conversation of two swineherds. After this the building proceeded successfully.[6] The small chapel became a famous place of pilgrimage during the fifth and sixth centuries.[7]

Her attribute is a candle, and she is sometimes also depicted with the devil, who is said to have blown it out when she went to pray in church at night.[8]

Death and burial

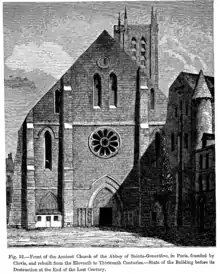

Clovis I founded an abbey where Genevieve might minister, and where she herself was later buried.[9] Under the care of the Benedictines, who established a monastery there, the church witnessed numerous miracles wrought at her tomb. As Genevieve was popularly venerated there, the church was rededicated in her name; people eventually enriched the church with their gifts. It was plundered by the Vikings in 847 and was partially rebuilt, but was completed only in 1177.

In 1129, when the city was suffering from an epidemic of ergot poisoning, this "burning sickness" was stayed after Saint Genevieve's relics were carried in a public procession. This was repeated annually with the relics being brought to the cathedral; Mme de Sévigné gave a description of the pageant in one of her letters. The relief from the epidemic is still commemorated in the churches of Paris.[10]

After the old church fell into decay, Louis XV ordered a new church worthy of the patron saint of Paris; he entrusted the Marquis of Marigny with the construction. The marquis gave the commission to his protégé Jacques-Germain Soufflot, who planned a neo-classical design. After Soufflot's death, the church was completed by his pupil, Jean-Baptiste Rondelet.

The Revolution broke out before the new church was dedicated. It was taken over in 1791 by the National Constituent Assembly and renamed the Panthéon, to be a burial place for distinguished Frenchmen. It became an important monument in Paris.

Though Saint Genevieve's relics had been publicly burnt at the Place de Grève in 1793 during the French Revolution, the Panthéon was restored to Catholic purposes in 1821. In 1831 it was secularized again as a national mausoleum, but returned to the Catholic Church in 1852. Though the Communards were said to have dispersed the relics (there is no proof of this allegation, the relics having been burnt in 1793), some managed to be recovered. In 1885 the Catholic Church reconsecrated the structure to St. Genevieve.

Canons of Saint Genevieve

About 1619 Louis XIII named Cardinal François de La Rochefoucauld abbot of Saint Genevieve's. The canons had been lax and the cardinal selected Charles Faure to reform them. This holy man was born in 1594, and entered the canons regular at Senlis. He was remarkable for his piety, and, when ordained, succeeded after a hard struggle in reforming the abbey. Many of the houses of the canons regular adopted his reform. In 1634, he and a dozen companions took charge of Saint-Geneviève-du-Mont of Paris. This became the mother-house of a new congregation, the Canons Regular of Ste. Genevieve, which spread widely over France.

The institute named after the saint was the Daughters of Ste. Geneviève, founded at Paris in 1636, by Francesca de Blosset, with the object of nursing the sick and teaching young girls. A somewhat similar institute, popular buriel Miramiones, had been founded under the invocation of the Holy Trinity in 1611 by Marie Bonneau de Rubella Beauharnais de Miramion. These two institutes were united in 1665, and the associates called the Canonesses of Ste. Geneviève. The members took no vows, but merely promised obedience to the rules as long as they remained in the institute. Suppressed during the Revolution, the institute was revived in 1806 by Jeanne-Claude Jacoulet under the name of the Sisters of the Holy Family.

Music

Marc-Antoine Charpentier, Pour le jour de Ste Geneviève, H.317, motet for 3 voices, 2 treble instruments ans continuo (? mid-1670)

See also

- Argol Parish close

- History of France

- Religion in France

- Roman Catholicism in France

- Saint Genevieve, patron saint archive

References

- Notes

- Evans, D. Ellis (1967). Gaulish personal names: a study of some Continental Celtic formations. Clarendon P.

- McNamara, Halborg, and Whatley 18.

- McNamara, Halborg, and Whatley 4.

- MacErlean, Andrew. "St. Genevieve." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 19 Jul. 2014

- Bentley, James (1993). A calendar of saints: the lives of the principal saints of the Christian Year. London: Little, Brown. p. 9. ISBN 9780316908139.

- Hinds, Allen Banks. Hinds, “Saint Genevieve”. A Garner of Saints, 1900. CatholicSaints.Info. 19 April 2017

- Alston, George Cyprian. "Abbey of Saint-Denis." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 2 December 2017

- Saint Geneviève in Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- Farmer, David Hugh (1997). The Oxford dictionary of saints (4. ed.). Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press. pp. 200–201. ISBN 9780192800589.

- Attwater.

- Bibliography

- Attwater, Donald; John, Catherine Rachel (1993). The Penguin Dictionary of Saints (3 ed.). New York: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-051312-4.

- McNamara, Jo Ann; Halberg, John E.; Whatley, E. Gordon (1992). Sainted Women of the Dark Ages. Durham: Duke UP. ISBN 978-0-8223-1216-1.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "St. Genevieve". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "St. Genevieve". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sainte Geneviève. |

- https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=120

- https://www.encyclopedia.com/people/philosophy-and-religion/saints/saint-genevieve

- http://www.catholic-saints.net/saints/st-genevieve.php

- https://www.loyolapress.com/catholic-resources/saints/saints-stories-for-all-ages/saint-genevieve/

- http://m.catholic-saints.info/roman-catholic-saints-a-g/saint-genevieve.htm