Titles of Mary

Mary is known by many different titles (Blessed Mother, Madonna, Our Lady), epithets (Star of the Sea, Queen of Heaven, Cause of Our Joy), invocations (Panagia, Mother of Mercy) and names associated with places (Our Lady of Loreto, Our Lady of Guadalupe).

| A series of articles on |

| Mother of Jesus |

| Chronology |

|---|

|

|

| Marian perspectives |

|

|

| Catholic Mariology |

|

|

| Marian dogmas |

|

|

| Mary in culture |

|

|

All of these descriptives refer to the same woman named Mary, the mother of Jesus Christ (in the New Testament), and are used differently by Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and some Anglicans. (Note: Mary Magdalene, Mary of Clopas, and Mary Salome are different women.)

Some descriptives of Mary are properly titles, dogmatic in nature, while some of them are invocations. Other descriptives are poetic or allegorical or have lesser or no canonical status, but form part of popular piety, with varying degrees of acceptance by Church authorities. There is another class of titles which refer to depictions of Mary in Catholic Marian art and in art generally. A rich range of Marian titles also belong to musical settings.[1]

Historical and cultural context

The relatively large number of titles given to Mary may be explained in several ways.[2] Some titles grew due to geographic and cultural reasons, e.g., through the veneration of specific icons. Others were related to Marian apparitions.

Mary's intercession is sought for a large spectrum of human needs in varied situations. This has led to the formulation of many of her titles (good counsel, Help of the Sick, etc.). Moreover, meditations and devotions on the different aspects of Mary's role in the life of Jesus have led to additional titles, such as Our Lady of Sorrows.[3] Still further titles have been derived from dogmas and doctrines, such as, the Assumption of Mary, Dormition of the Mother of God and Immaculate Conception.

The veneration of Mary or "devotional cult" was consolidated in the year 431 when, at the Council of Ephesus, the descriptive, Theotokos, or Mary the bearer (or mother) of God, was declared a dogma. Thereafter Marian devotion, centred on the subtle and complex relationship between Mary, Jesus, and the Church, began to flourish, first in the East and later in the West.

The Reformation diminished Mary's role in many parts of Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Council of Trent and Counter Reformation intensified Marian devotion in the Western Europe. Around the same period, Mary became an instrument of evangelisation in the Americas and parts of Asia and Africa, e.g. gaining impetus from reported apparitions at Our Lady of Guadalupe, which resulted in a large number of conversions to Christianity in Mexico.

Following the Reformation, baroque literature on Mary experienced unprecedented growth, with over 500 instances of Mariological writings during the 17th century alone.[4] During the Age of Enlightenment, the emphasis on scientific progress and rationalism put Catholic theology and Mariology often on the defensive later in the 18th century. Books, such as The Glories of Mary by Alphonsus Liguori, were written in defence of the cult of Mary.

Dogmatic titles

- Mother of God: The Council of Ephesus decreed in 431 that Mary is Theotokos ("God-bearer") because her son Jesus is both God and man: one Divine Person with two natures (divine and human).[5] This name was translated in the West as "Mater Dei" or Mother of God. From this derives the title "Blessed Mother".

- Virgin Mary: The doctrine of the perpetual virginity of Mary developed early in Christianity and was taught by the early Fathers, such as, Irenaeus and Clement of Alexandria (and others).[6] In the fourth century "ever-virgin" became a popular title for Mary.[7] Variations on this include the "Virgin Mary", the "Blessed Virgin", the "Blessed Virgin Mary", and "Spouse of the Holy Spirit". The perpetual virginity of Mary was declared a dogma by the Lateran Council of 649.

- Immaculate Conception: The dogma that Mary was conceived without original sin was defined in 1854, by Pope Pius IX's apostolic constitution Ineffabilis Deus. This gave rise to the titles of "Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception" and "Queen Conceived Without Original Sin". The Immaculate Conception is also honored under the titles of Our Lady of Caysasay (Philippines),[8] Our Lady of the Gate of Dawn in Vilnius, Our Lady of Guidance, and Our Lady of Salambao, also in the Philippines.

- Assumption: The belief that the Virgin Mary was assumed body and soul into heaven upon completing the course of her earthly life was declared a dogma in 1950 by Pope Pius XII in the apostolic constitution Munificentissimus Deus. The titles "Our Lady of Assumption" and "Queen Assumed Into Heaven" derive from this. This dogma is also reflected in devotion to Our Lady of Ta' Pinu on Malta.

In the Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches the Assumption of Mary may be translated as the Dormition of the Mother of God; it is an important feast day, not based on a scriptural canon but affirmed by tradition.

Early titles of Mary

“Our Lady” is a common title to give to Mary as a sign of respect and honor. In French she is called "Notre Dame" and in Spanish she is "Nuestra Señora".[9]

- Mary was identified as the "New Eve" as early as the later half of the Second Century. Justin Martyr (100–165) draws the connection in his Dialogue with Trypho. This idea is later expanded by Irenaeus.[10]

- John Chrysostom, in 345, was the first person to use the Marian title Mary Help of Christians as a devotion to the Virgin Mary. Don Bosco promoted devotion to Mary under this title.

- Stella Maris or Our Lady, Star of the Sea is an ancient title for the Virgin Mary, used to emphasize her role as a sign of hope and a guiding star for Christians. It is attributed to Jerome and cited by Paschasius Radbertus.

| English | Latin | Greek | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mary | Maria | Mariam (Μαριάμ), Maria (Μαρία) | Arabic: Maryām (مريم), Chinese: (瑪利亞), Coptic: Maria (Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ), French: Marie, German: Maria, Italian: Maria, Judeo-Aramaic: Maryām (מרים), Maltese: Marija, Portuguese: Maria, Russian: Marija (Мария), Spanish: María, Syriac: Mariam, Vietnamese: Maria |

| "Full of Grace", "Blessed", "Most Blessed" | Gratia plena, Beata, Beatissima | kecharitomene[11] (κεχαριτωμένη) | from the angel's greeting to Mary in Luke 1:28; |

| "Virgin", "the Virgin" | Virgo | Parthenos[12][13] (Παρθένος) | Greek parthenos used in Matthew 1:22; Ignatius of Antioch refers to Mary's virginity and motherhood (ca. 110); |

| "Cause of our Salvation" | causa salutis[14] | according to Irenaeus of Lyons (150–202); | |

| "Mother of God" | Mater Dei | Meter Theou (Μήτηρ Θεοῦ) | often abbr. ΜΡ ΘΥ in Greek iconography; |

| "God-bearer" | Deipara, Dei genitrix | Theotokos (Θεοτόκος) | lit. "one who bears the One who is God"; a common title in Eastern Christianity with christological implications; adopted officially during Council of Ephesus (431) in response to Nestorianism, which questioned the Church's teaching that Jesus Christ's nature was unified; |

| "Ever-virgin" | semper virgo | aei-parthenos[12] (ἀειπάρθενος) | |

| "Holy Mary", "Saint Mary" | Sancta Maria | Hagia Maria[12] (Ἁγία Μαρία) | Greek invocation is infrequent in contemporary Eastern Christianity;[15] |

| "Most Holy" | Sanctissima, tota Sancta[16] | Panagia (Παναγία) | |

| "Most Pure" | Purissima | ||

| "Immaculate" | immaculata | akeratos[12] (ἀκήρατος) | |

| "Lady", "Mistress" | Domina | Despoina[12] (Δέσποινα) | related, "Madonna" (Italian: Madonna, from ma "my" + donna "lady"; from Latin domina); also, "Notre Dame" (French: Notre Dame, lit. "our lady"); |

| "Queen of Heaven" | Regina Coeli, Regina Caeli | Mary is identified with the figure in Revelation 12:1; | |

Papal actions

- After the Battle of Lepanto in 1521, Pope Pius V instituted the feast of the Blessed Virgin Mother of Victory.

- The first Marian image pontifically crowned was Lippo Memmi’s painting of La Madonna della Febbre (Madonna of Fever) in the sacristy of Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome on 27 May 1631, by Pope Urban VIII by the Vatican Chapter.

- The doctrine of the Immaculate Conception of Mary was adopted as church dogma when Pope Pius IX promulgated Ineffabilis Deus in 1854.[17]

- The encyclical Ad diem illum of Pope Pius X commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the dogma of Immaculate Conception

- During World War I, Pope Benedict XV added the invocation Mary Queen of Peace to the Litany of Loreto.

- Pope Pius XII issued the Apostolic constitution Munificentissimus Deus to define ex cathedra the dogma of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

- In 1954 the papal encyclical Ad Caeli Reginam, issued by Pope Pius XII, explained how Mary is Queen of Heaven[18]

- In 1960 Pope John XXIII changed the title of the "Feast of the Holy Rosary" (formerly the "Feast of Our Lady of Victory") to the "Feast of Our Lady of the Rosary."

- Pope John Paul II's 1987 encyclical Redemptoris Mater took the step of addressing the role of the Virgin Mary as Mediatrix.

- Several Papal actions over the centuries decreed the appellation "Queen of Poland" for Mary, following the solemn vows of King John Casimir Vasa before the papal legate and assembled episcopate, proclaiming Mary "Queen" of all his lands, at Lwów Cathedral on 1st April 1656.[19] The last act was of John Paul II on 1st April 2005, on the eve of his death.[20] The feast of The Most Holy Virgin Mary, Queen of Poland is on 3 May.

Descriptive titles of Mary related to visual arts

| Image Type | Typical Art Style | Description |

|---|---|---|

Eleusa icon |

Byzantine | In this 12th c. depiction by an unknown artist, Mary holds her baby's face to her cheek as an expression of maternal tenderness. The evocative pose was copied two centuries later by the great Russian painter Andrei Rublev. The original was saved from destruction several times in its history. After the Russian Revolution it was housed in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, but representations from the Russian Orthodox Church ensured it is once again in a nearby church, where services are held; |

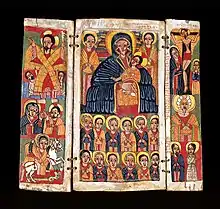

Hodegetria |

Byzantine | Mary holds Christ in her left hand and with her right hand she "shows the way" by pointing to Him; |

Sedes Sapientiae |

Romanesque | Christ is seated in His mother Mary's lap, symbolically the "Throne of Wisdom"; |

"Gothic Madonna" |

Gothic | Based loosely on Byzantine Hodegetria iconography; typically depicts a standing, smiling Mary and playful Christ Child; considered one of the earliest depictions of Mary that is strictly Western;[21] |

Madonna Lactans |

Gothic and Renaissance | The Virgin is depicted breastfeeding the Holy Infant. Our Lady Nursing, as painted in the Catacomb of Priscilla in Rome, c. A.D. 250, is one of the earliest depictions (if not the earliest depiction) of Mary;[22] Discouraged by the Council of Trent and rare subsequently. |

Mater Misericordiae |

Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque | A regal, celestial Mary is depicted covering the faithful in her protective mantle; first arose in the late 13th century in Central Europe and Italy; depiction is commonly associated with plague monuments.[23] |

Maestà |

Gothic | Mary is seated in majesty, holding the Christ Child; based on Byzantine Nikopoia iconography; |

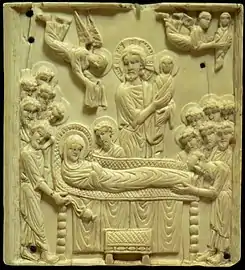

Pietà |

Renaissance | Mary cradles the dead body of Jesus Christ after his crucifixion; this type emerged first in the 13th century in Germany as an Andachtsbild or devotional icon relating to grief; Italian Pietàs appeared in the 14th century;[24] Michelangelo's Pietà (1498–1499) is considered a masterpiece; |

Mater Amabilis |

Renaissance, Baroque | Iconic Western depiction with many variations; based loosely on Byzantine Glykophilousa ("sweet kisses") iconography; Mary turns her gaze away from the Christ Child as she contemplates His future Passion; Renaissance emphasis on classical ideal types, realistic human anatomy, and linear perspective are evident; |

Madonna della seggiola |

Renaissance round painting | Mary with toddlers Jesus and his cousin, John the Baptist, looking on, painted 1513-1514 during Raphael's Roman period. The unusual non-linear style and colouring is more reminiscent of Titian and Sebastiano del Piombo and bears out their influence. This painting has been greatly admired by many people, including Nathaniel Hawthorne, and by subsequent painters of the stature of Ingres.[25] |

Devotional titles

In the Loreto Litanies Mary's prayers are invoked under more than fifty separate titles, such as "Mother Most Pure", "Virgin Most Prudent", and "Cause of Our Joy".[26]

Other devotional titles include:

- Ark of the Covenant

- Comfort (or Help) of the Afflicted

- Our Lady, Gate of the Dawn

- Holy Mary

- Immaculate Heart of Mary

- Mother of Christ

- Mother of Mercy

- Mother of Sorrows

- Mother for the Journey

- Mother of the Church

- Mystical Rose

- Our Lady of the Annunciation

- Our Lady of Charity

- Our Lady of Providence

- Our Lady of Ransom

- Our Lady of Solitude

- Our Lady, Star of the Sea

- Queen of All Saints

- Queen of Angels

- Queen of Apostles

- Queen of Confessors

- Queen of Families

- Queen of Martyrs

- Queen of Patriarchs

- Queen of Prophets

- Queen of Virgins

- Queen of the World (in Latin Regina mundi)

- Refuge of Sinners

- Salus Populi Romani (Salvation of the People of Rome)

- Untier of Knots (also, Undoer of Knots)

Theological Mariology

With the exception of the Jesus Christ, who is believed to have a twofold nature, both human and divine, (dyophysitism), the Blessed Virgin Mary is considered among many Christians to be the unique human being about whom there is a dogma. She is connected to four different dogmas and numerous Marian titles. Christian invocations, titles, and art bear witness to the prominent role she has been accorded in the history and programme of salvation in parts of Christendom, although this is not shared by many (mainly reformed) Christian churches.

In the Hail Mary prayer, she is addressed as "full of grace" by Archangel Gabriel of the Annunciation speaking in the Name of God. The Nicene Creed, declares that Jesus was "incarnate by the Holy Ghost and of the Virgin Mary, and was made man,". This has given rise to the descriptive, "spouse of the Holy Spirit".

Tradition has it that the Virgin Mother of God was anointed by the Holy Spirit, hence putting her on a par with the anointing of the Kings, Prophets, Judges, and High Priests of Israel, as Jesus Christ is said to have been. This in turn opens the way to titles such as:

- Advocate of the Church (like the judges of Israel)

- Mediatrix of all graces[27] (like a High Priest of Israel),

- Queen of Angels (like the kings of Israel): the Coronation of the Virgin paintings represent the hierarchy of angels of God while starting to serve Mary forever, after she has accepted to become the Mother of God.

- Marian apparitions are said to testify to Mary's gift of prophecy.

In the Roman Catholic and in the Orthodox Churches, the Virgin Mother of God is venerated in a special form expressed in Greek as hyperdulia, that is, secondary only to the adoration reserved for the Triune God. She is venerated and honoured in this way since no other being--whether angelic or human--has greater power than Mary to intercede with God in the distribution of Grace to His children.

Titles associated with devotional images

- The Black Madonna (French: Vierge Noire, Catalan: La Moreneta) is a statue or painting of Mary, generally of the 12th to 15th centuries, where she often with the infant Jesus, are depicted as having swarthy or black skin.[28] There are over 450 Black Madonnas in Europe alone. The title given to Mary, usually reflects the location of the image. The Black Madonna of Częstochowa, the Virgin of Candelaria, Our Lady of Ferguson, and Our Lady of Peace and Good Voyage are noted examples.

- Mother of Good Counsel (Latin: Mater boni consilii) is a title given to the Blessed Virgin Mary, after a painting said to be miraculous, now found in the thirteenth century Augustinian church at Genazzano, near Rome, Italy.

- Mother Thrice Admirable refers to Mary depicted in a painting as Our Lady Refuge of Sinners. Devotion to this invocation of Mary is significant to the Schoenstatt Movement.

Titles of images related to epithets include:

Titles of images related to places of worship include:

- Our Lady of Bethlehem

- Our Lady of Chartres

- Our Lady of Combermere

- Our Lady of Covadonga

- Our Lady of Ipswich

- Notre-Dame de Liesse

- Our Lady of Atocha[29]

- Santa Marian Kamalen (Guam)

- Our Lady of Korattymuthy (India)

- Our Lady of Lebanon

- Our Lady of Loreto

- Our Lady of Manaoag

- Our Lady of La Naval de Manila

- Our Lady of Nazaré

- Our Lady of Peñafrancia

- Our Lady of Piat

- Our Lady of Porta Vaga

- Our Lady of Turumba

Titles associated with apparitions

.jpg.webp)

- Our Lady of Akita

- Our Lady of Banneux

- Our Lady of Beauraing

- Our Lady of Cabeza

- Our Lady of Caravaggio

- Our Lady of China

- Our Lady of Coromoto

- Our Lady of Fátima

- Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Our Lady of Good Health

- Our Lady of Good Help

- Mother of the Word (Kibeho)

- Our Lady of Knock

- Our Lady of La Salette

- Our Lady of La Vang

- Our Lady of Laus

- Our Lady of Lourdes

- Our Lady of the Miraculous Medal

- Our Lady of Mount Carmel

- Our Lady of the Pillar

- Our Lady of the Snows

- Our Lady of Vallarpadam

- Our Lady of Walsingham

- Our Lady of Zeitoun

Latin America

A number of titles of Mary found in Latin America pertain to cultic images of her represented in iconography identified with a particular already existent title adapted to a particular place. Our Lady of Luján in Argentina refers to a small terracotta image made in Brazil and sent to Argentina in May, 1630. Its appearance seems to have been inspired by Murillo's Immaculates. Our Lady of Copacabana (Bolivia): is a figure related to devotion to Mary under the title "Most Blessed Virgin de la Candelaria, Our Lady of Copacabana". About four feet in height, the statue was made by Francisco Tito Yupanqui around 1583 and is garbed in the colors and dress of an Inca princess.[30]

- Field Marshal of the Army of Paraguay[31]

- Nossa Senhora dos Aflitos (Our Lady of the Troubled), Brazil[29]

- Nuestra Señora de la Anunciación (Our Lady of the Annunciation)[29]

- Nuestra Señora de la Asunción (Our Lady of the Assumption)

- Our Lady of Aparecida

- Our Lady of Carmel of the Maipú[30]

- Our Lady of Guadalupe, Mexico City

- Our Lady of the Rosary of Chiquinquirá

- Our Lady of the Rosary of San Nicolás, Buenos Aires, Argentina[32]

- Virgin de la soledad de Parral (Our Lady of Solitude of Parral), Parral, Mexico

- Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles (Our Lady of the Angels), Costa Rica[30]

- Virgin of Suyapa (Honduras)

- Virgin of the Thirty-Three

- Rainha da Floresta (Queen of the Forest), Santo Daime in Brazil

Titles in the Orthodox Church

Theotokos means "God-bearer" and is translated as "Mother of God". This title was given to Mary at the Third Ecumenical Council in Ephesus in 431 AD.(cf. Luke 1:43).[33]

- Life-giving Spring

- Our Mother the Holy Virgin (John 19:27)[33]

- Our Lady of Kazan

- Our Lady of St. Theodore

- Panagia

- Panagia tis Angeloktistis

- Panagia Episkopi

- Panagia Portaitissa

- The Queen Who is by the Right Side of the King (from Ps.45:9)[33]

- Theotokos of Bogolyubovo

- Theotokos of Buchyn

- Theotokos of Kursk

- Theotokos of Miasena

- Theotokos of Tikhvin

- Theotokos of Tolga

- Theotokos of Vladimir

Titles of Mary in Islam

The Qur'an refers to Mary (Arabic: مريم, romanized: Maryam) by the following titles:

- Ma'suma - "She who never sinned"

- Mustafia - "She who is chosen"

- Nur - "Light". She has also been called Umm Nur ("Mother of one who was Light"), in reference to 'Isa

- Qānitah - the term implies constant submission to Allah, as well as absorption in prayer and invocation.

- Rāki’ah - "She who bows down to Allah in worship"

- Sa’imah - "She who fasts"

- Sājidah - "She who prostrates to Allah in worship"

- Siddiqah - "She who accepts as true", "She who has faith", or "She who believes sincerely totally"

- Tāhirah - "She who was purified"

See also

- Agni Parthene

- Ave Maria ... Virgo serena

- Catholic Marian art

- Catholic Marian church buildings

- Catholic Marian music

- Intercession of the saints

- Litany of the Blessed Virgin Mary

- Magnificat

- Marian apparitions

- Mary of Egypt

- Roman Catholic Mariology

- Salve Regina

- Stabat Mater

- Theotokion

- Veneration of Mary in Roman Catholicism

Citations

- The History and Use of Hymns and Hymn-Tunes by David R Breed 2009 ISBN 1-110-47186-6 page 17

- “Why does Mary have So Many Different Titles?” All About Mary, International Marian Research Institute, University of Dayton.

- Tavard, George Henry, The thousand faces of the Virgin Mary 1996 ISBN 0-8146-5914-4 p. 95

- Roskovany, A., conceptu immacolata ex monumentis omnium seculrorum demonstrate III, Budapest 1873

- by Braaten, Carl E. and Jenson, Robert W., Mary, Mother of God, 2004 ISBN 0802822665 p. 84

- Maas, Anthony. "Virgin Birth of Christ." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 10 April 2016

- Wuerl, Donald W. and Stubna, Kris D., The Teaching of Christ: A Catholic Catechism for Adults, Our Sunday Visitor Publishing, 2004, ISBN 9781592760947

- "In Honor of Nuestra Señora de Guia", De Anda (2009-11-22),

- Hargett, Malea. "Marian titles chosen for one out of four churches in diocese", Arkansas Catholic, Diocese of Arkansas, May 20, 2006

- Mauriello, Matthew R., “Mary the New Eve,” Frei Francisco.

- "...Byzantine inscriptions from Palestine...in the sixth [century]....fourteen inscriptions invoke "Holy Mary" (Hagia Maria), eleven more hail her as Theotokos; others add the attribution of "Immaculate" (Akeratos), "Most Blessed" (Kecharitomene), "Mistress" (Despoina), "Virgin" or "Ever-Virgin" (Aei-Parthenos)." (Frend 1984, p. 836)

- Frend 1984, p. 836.

- "Blue Letter Bible" lexicon results for parthenos Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- Irenaeus of Lyons (Adversus Haereses 3.22.4).

- The Titles of Saints, Orthodox Holiness, December 18, 2005

- "Universität Mannheim". www.uni-mannheim.de. 3 January 2019.

- Reynolds, Brian (2012). Gateway to Heaven: Marian Doctrine and Devotion, Image and Typology in the Patristic and Medieval Periods, Volume 1. New City Press. ISBN 9781565484498.

- Pope Pius XII (11 October 1954). "Ad Caeli Reginam". Roman Catholic Church. Archived from the original on 7 October 2010.

- "Śluby króla Jana Kazimierza, złożone dnia 1 kwietnia 1656 roku" [King John Casimir's vows made on 1 April 1656] (in Polish). Konferencja Episkopatu Polski i Wydawnictwo Pallottinum. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- Paweł Zuchniewicz. "Ostatni dokument Jana Pawła II" [The Last Document of Pope John Paul II] (in Polish). Retrieved 29 September 2019.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Madonna. (2008). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 17, 2008, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online:

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 November 2009. Retrieved 24 August 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Jeep 2001, p. 393.

- Watts, Barbara. "Pietà". Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press, Retrieved February 17, 2008, http://www.groveart.com/

- Zoffany Archived 2014-10-18 at the Wayback Machine, RoyalCollection.org, retrieved 18 October 2014

- "The Loreto Litanies". The Holy See. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Mark Alessio (31 January 2006). "Mary, advocate of the Church and Mediatrix of all graces". catholicism.org. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016.

- Duricy, Michael P., “Black Madonnas: Origin, History, Controversy,” All About Mary, International Marian Research Institute, University of Dayton.

- "Titles of Mary", Regis University

- “Latin American Titles of Mary,” All About Mary, International Marian Research Institute, University of Dayton.

- Paraguay: South America's Lewis Carroll world

- Website of Center for the Promotion of Devotion, Sanctuary of Mary of the Rosary of San Nicolás]

- "Titles of the Holy Theotokos, Saint Mary", Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, Diocese of Los Angeles

References

- Frend, W. H. C. (1984). The Rise of Christianity. Fortress Press. ISBN 0-8006-1931-5.

- Jeep, John M. (2001). Medieval Germany: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 0-8240-7644-3.

External links

- Archaeological project to collect all epithets of Mary in Greek, Latin, and Syriac

- International Marian Research Institute at the University of Dayton. The Institute, a leading center for research and scholarship on the Blessed Virgin Mary, has a vast presence in cyberspace.

- List of 6,000 Catholic titles of Mary

- Marian Library at the University of Dayton. The Marian Library is the world’s largest repository of books, periodicals, artwork, and artifacts on Mary, the mother of Jesus Christ.

- Eastern Orthodox understanding of saints' titles

- Raised to Heaven because Co-Redemptrix on earth. Thoughts on the foundation of the Catholic dogma. Lecture by Monsignor Brunero Gherardini. Explains the meaning of the Marian titles Assumpta, Mediatrix, Co-Redemptrix.

.jpg.webp)