Georgia–Turkey border

The Georgia–Turkey border (Georgian: საქართველო–თურქეთის საზღვარი,Turkish: Gürcistan–Türkiye sınırı) is 273 km (170 m) in length and runs from the Black Sea coast in the west to the tripoint with Armenia in the east.[2]

| Georgia-Turkey border საქართველო-თურქეთის საზღვარი Gürcistan-Türkiye sınırı | |

|---|---|

| |

| Characteristics | |

| Entities | |

| Length | 276 km (171 mi)[1] |

Description

The border starts in the west on the Black Sea just south of Sarpi and then proceeds overland eastwards via a series of irregular lines; it then arcs broadly south-eastwards, cutting across Kartsakhi Lake, and down to the Armenian tripoint. The western third of the border is taken up by Georgia's Autonomous Republic of Adjara.

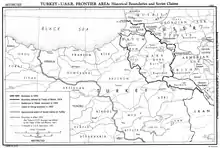

History

During the 19th the Caucasus region was contested between the declining Ottoman Empire, Persia and Russia, which was expanding southwards. Russia had conquered most of Persia's Caucasian lands by 1828 and then turned its attention to the Ottoman Empire.[3] By the 1829 Treaty of Adrianople (ending the Russo-Turkish War of 1828-9) Russia gained most of modern Georgia (including Imeretia, Mingrelia and Guria), with a frontier being delimited situated roughly north of the current Georgia-Turkey boundary.[3][4][5][6]

By the Treaty of San Stefano, ending the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), Russia gained further land in what is now eastern Turkey, extending the Ottoman-Russian frontier south-westwards.[4][7][8] Russia's gains of Batumi, Kars and Ardahan were confirmed by the Treaty of Berlin (1878), though it was compelled to hand back part of the area around Bayazid (modern Doğubayazıt) and the Eleşkirt valley.[3][4][9]

During the First World War Russia invaded the eastern areas of the Ottoman Empire. In the chaos following the 1917 Russian Revolution the new Communist government hastily sought to end its involvement in the war and signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in 1918 with Germany and the Ottoman Empire.[3] By this treaty, Russia handed back the areas gained by the earlier Treaties of San Stefano and Berlin.[4]

Seeking to gain independence from both empires, the peoples of the southern Caucasus had declared the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic in 1918 and started peace talks with the Ottomans.[10][11] Internal disagreements led to Georgia leaving the federation in May 1918, followed shortly thereafter by Armenia and Azerbaijan. With the Ottomans having invaded the Caucasus and quickly gained ground, the three new republics were compelled to sign the Treaty of Batum on 4 June 1918, by which they recognised the pre-1878 border.[12][13] Ottoman gains in Armenia were consolidated further by the Treaty of Aleksandropol (1920).[4] Meanwhile, Russia recognised the independence of Georgia via the Treaty of Moscow (1920).[14]

With the Ottoman Empire defeated in Europe and Arabia, the Allied powers planned to partition it via the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres.[4][15] The treaty recognised Georgian and Armenian independence, granting both vast lands in eastern Turkey, with an extended Armenia-Georgia border to be decided at a later date; Georgia was to gain much of Lazistan. Turkish nationalists were outraged at the treaty, contributing to the outbreak the Turkish War of Independence; the Turkish success in this conflict rendered Sèvres obsolete.[4][3] In 1920 Russia's Red Army had invaded Azerbaijan and Armenia, followed by the Red Army invasion of Georgia in 1921 which ended the independence of Georgia. The Ottomans used the opportunity to invade south-west Georgia, taking Artvin, Ardahan, Batumi and other lands. In order to avoid an all-out Russo-Turkish war the two nations signed the Treaty of Moscow in March 1921, which created a modified Soviet-Ottoman border.[4][16][17][3] However further fighting took place on the ground and the talks stalled; the treaty's provisions were later confirmed by the Treaty of Kars of October 1921, finalising what is now the Georgia–Turkey border at its current position.[4] Turkey relinquished its claim to Batumi with the proviso that an autonomous Adjara region be created to protect that area's largely Muslim population. The border was then demarcated on the ground in March 1925-July 1926 by a joint Soviet-Turkish commission.[4][3] Turkey's independence had been recognised by the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne.[18]

Georgia was initially incorporated along with Armenia and Azerbaijan in the Transcaucasian SFSR within the USSR, before being split off as the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic in 1936. The Kars Treaty border remained, despite occasional Soviet protests that it should be amended, notably in 1945.[3][19][20] Turkey, backed by the US, refused to discuss the matter, and the Soviets, seeking better relations with their southern neighbour, dropped the issue.[21][4]

Following the collapse of the USSR in 1991 Georgia gained independence and inherited its section of the Turkey-USSR border. Turkey recognised Georgian independence on 16 December 1991. The Protocol on Establishment of Diplomatic Relations between the two countries was signed on 21 May 1992 by which their mutual frontier was confirmed.[22]

Settlements near the border

Crossings

There are three crossings along the entire border, two for vehicular traffic and one for vehicular and rail traffic.[23][24]

| Province | Province | Opened | Route in Turkey | Route in Georgia | Status | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarp | Artvin | Sarpi | Adjara | 31 August 1988 | Open | ||

| Posof-Türkgözü | Ardahan | Vale | Samtskhe–Javakheti | 12 July 1995 | Open | ||

| Çıldır-Aktaş | Ardahan | Kartsakhi | Samtskhe–Javakheti | 24 July 1995 | Open |

Since 2017 and the opening of the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars railway it is also possible to cross the border by rail.[25]

See also

References

- "Türkiyenin Komşuları ve Coğrafi Sınırları". 14 February 2016. Archived from the original on 14 February 2016.

- CIA World Factbook - Turkey, retrieved 6 April 2020

- The boundary between Turkey and the USSR (PDF), January 1952, retrieved 8 April 2020

- International Boundary Study No. 29 – Turkey-USSR Boundary (PDF), 24 February 1964, retrieved 8 April 2020

- John Emerich Edward Dalberg Acton (1907). The Cambridge Modern History. Macmillan & Co. p. 202.

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 1154. ISBN 978-1851096725.

The Turks recognize Russian possession of Georgia and the khanates of Yerevan (Erivan) and Nakhchivan that had been ceded by Persia to Russia the year before.

- Hertslet, Edward (1891), "Preliminary Treaty of Peace between Russia and Turkey. Signed at San Stefano 19 February/3 March 1878 (Translation)", The Map of Europe by Treaty; which have taken place since the general peace of 1814. With numerous maps and notes, IV (1875-1891) (First ed.), London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, pp. 2672–2696, retrieved 2013-01-04

- Holland, Thomas Erskine (1885), "The Preliminary Treaty of Peace, signed at San Stefano, 17 March 1878", The European Concert in the Eastern Question and Other Public Acts, Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 335–348, retrieved 2013-03-04

- Holland, Thomas Erskine (1885), "The Preliminary Treaty of Peace, signed at San Stefano, 17 March 1878", The European Concert in the Eastern Question and Other Public Acts, Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 305–06, retrieved 2013-03-04

- Richard Hovannisian, The Armenian people from ancient to modern times, pp. 292–293, ISBN 978-0-333-61974-2, OCLC 312951712 (Armenian Perspective)

- Ezel Kural Shaw (1977), Reform, revolution and republic : the rise of modern Turkey (1808-1975), History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, 2, Cambridge University Press, p. 326, OCLC 78646544 (Turkish Perspective)

- Charlotte Mathilde Louise Hille (2010), State Building and Conflict Resolution in the Caucasus, BRILL, p. 71, ISBN 978-9-004-17901-1

- Alexander Mikaberidze (2011), Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World, ABC-CLIO, p. 201, ISBN 978-1-598-84337-8

- Lang, DM (1962). A Modern History of Georgia, p. 226. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Helmreich, Paul C. (1974). From Paris to Sèvres: The Partition of the Ottoman Empire at the Peace Conference of 1919–1920. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University Press.

- Tsutsiev, Arthur (2014). Atlas of the Ethno-Political History of the Caucasus. Translated by Nora Seligman Favorov. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0300153088.

- King, Charles (2008). The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-0195177756.

- Treaty of Peace with Turkey signed at Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, 24 July 1923, retrieved 28 November 2012

- Khrushchev, Nikita S. (2006). Sergei Khrushchev (ed.). Memoirs of Nikita Khrushchev: Reformer, 1945-1964. Translated by George Shriver. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press. p. 426. ISBN 978-0271058597.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (1993). Looking toward Ararat. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 165–169. ISBN 978-0253207739.

- Ro'i, Yaacov (1974). From Encroachment to Involvement: A Documentary Study of Soviet Policy in the Middle East, 1945-1973. Transaction Publisher. pp. 106–107.

- http://www.mfa.gov.tr/relations-between-turkey-and-georgia.en.mfa

- (2015) Tim Burford, Bradt Travel Guide - Georgia, pgs. 60-1

- Caravanistan - Georgia-Turkey border crossings, retrieved 8 April 2020

- "Baku-Tbilisi-Kars Railway Line Officially Launched". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 30 October 2017. Retrieved 31 October 2017.