Germán Busch

Germán Busch Becerra (23 March 1904 – 23 August 1939) was a Bolivian military officer and war hero who served as the 36th president of Bolivia.

Germán Busch | |

|---|---|

Official photograph by Luigi Domenico Gismondi, c. 1938 | |

| 36th President of Bolivia | |

| In office 13 July 1937 – 23 August 1939 | |

| Vice President | None (1937) Enrique Baldivieso (1938–1939) |

| Preceded by | David Toro |

| Succeeded by | Carlos Quintanilla (interim) |

| In office 17 May 1936 – 22 May 1936 De facto | |

| Preceded by | José Luis Tejada Sorzano |

| Succeeded by | David Toro |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Germán Busch Becerra 23 March 1904 San Javier, Santa Cruz, or El Carmen de Iténez, Beni, Bolivia |

| Died | 23 August 1939 (aged 35) La Paz, Bolivia |

| Cause of death | Suicide |

| Nationality | Bolivian |

| Political party | Military Socialist (trend) |

| Spouse(s) | Matilde Carmona Rodo |

| Children |

|

| Parents | Pablo Busch Wiesener Raquel Becerra Villavicencio |

| Relatives | Alberto Natusch (nephew) |

| Education | Military College of the Army |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Nickname(s) | Camba Busch |

| Allegiance | Bolivia |

| Branch/service | Bolivian Army |

| Years of service | 1922–1937 |

| Rank | Lieutenant colonel |

| Battles/wars | Chaco War |

| Awards | Order of the Condor of the Andes |

After serving with distinction in the bloody Chaco War (1932–1935), Busch led the military's ouster of President José Luis Tejada Sorzano in 1936, briefly holding power as de facto president for less than a week before transmitting command to Colonel David Toro. He was again de facto ruler the following year after leading a popular movement which achieved Toro's resignation. Busch was later elected by the National Convention in 1938, only to declare himself dictator just one year later.

Busch's brief three year reign was marked by several major legal and political developments, including economic and social reforms. An enigmatic character who came from outside the political realm, he was wrapped in legend and controversy, even about his birthplace. His sudden and unexpected death in office is still disputed as either suicide or an assassination.[1]

Early life and education

Germán Busch was born on 23 March 1904 to Pablo Busch Wiesner, a physician and German immigrant from Münster, and Raquel Becerra Villavicencio, a Bolivian of Italian descent.[2] His exact place of birth has been a source of historical dispute; some historians point to San Javier, in central Bolivia's tropical coffee-growing Santa Cruz Department, while others to El Carmen de Iténez, in the northern cattle-growing Beni Department. A descendant of the Busch family declared publicly that Germán Busch was born in San Javier, Santa Cruz, pointing to a will by Pablo Busch Wiesener, in whose inheritance deeds he places the names of all his children, with their corresponding places of birth. However, historian Robert Brockmann maintains that the testament is incorrect, not a result of malice on the part of Pablo Busch, but due to the fact it was written in extremis as Busch Wiesener was at the point of death.[3] Brockmann points to the claim by Busch's mother Raquel Becerra, with sworn testimonies collected by Rógers Becerra and Arnaldo Lijerón, which states that her son was born in El Carmen.

At some point in Busch's childhood, his father went to Germany, while sending the young boy and his mother to live in the town of Trinidad where he would spend a large part of his childhood. In 1922, at the age of 18, he entered the Military College of the Army in the capital of La Paz where he achieved the rank of Second Lieutenant of Cavalry in 1927 and was assistant to the orders of the General Staff.[4] In 1931, he was promoted to Lieutenant and awarded the Order of the Condor of the Andes for his expedition to the missions of San Ignacio de Zamucos in the Chaco.

Chaco War

In September 1932 the Chaco War broke out between Bolivia and Paraguay where he participated in that conflict's first engagement at the battle of Boquerón. In the first stages of the Chaco War, he saved an entire division from certain destruction[4] during the battle of Gondra, as well as a part of his own cavalry regiment -fighting on foot- which he drove out from the Campo Vía pocket.[5]He would go on to be promoted to captain for his bravery in various actions after the battle of Boquerón .

As a young officer, he took part, and carried out the bulk of the action, in the highly controversial coup d'état that overthrew the Constitutional President Daniel Salamanca on 27 November 1934, right in the middle of the war and only twelve kilometers from the front line. The reason for this was the constant butting of heads of the Bolivian High Command with Salamanca over the conduct of the war and the issuing of military appointments and promotions. When President Salamanca decided to travel in-person to the theater of operations to dismiss General Enrique Peñaranda and replace him, the main leaders of the Bolivian army ordered cannons to be aimed at the chalet of the Staudt house where the president was staying. Major Busch, on the orders of Colonel David Toro, surrounded the residence and forced Salamanca's resignation. Wishing to maintain appearances of democratic government, the military chose to allow Vice President José Luis Tejada Sorzano to assume the presidency and see the country through to the end of the war.[6][7]

Political rise

Bolivia's ultimate loss against Paraguay in June of 1935 plunged the country into a period of turmoil as the old political order lost a majority of its support.[8] While political movements calling themselves "socialists" began to crop up across the country, the military found itself in the midst of its own internal power struggle. While many blamed the loss of the Chaco War on the oligarchic traditional parties, the senior officer corps of the army was also largely discredited for its failed tactics. It would not take long for the young officer corps, which had risen in the ranks at an incredibly fast pace during the conflict, to force the old guard of the military to make way for new leadership. The young officers, sympathetic to the left-wing movements being formed inside the country, soon coalesced around Germán Busch who on 13 September 1935 formed the Legion of Veterans (LEC), which quickly became a powerful political organization.[9] But for all his military tact and leadership ability, Busch lacked a political mind and was incapable of forming a coherent ideology. As such, he and the young officers around him eventually settled on the more politically-minded Colonel David Toro to lead their movement.[8]

1936 coup

Elsewhere in Bolivia, labor unions had brought the country into crisis through debilitating strikes demanding higher wages and benefits in the face of rapid inflation.[10] President Tejada Sorzano was viewed by both the civilian populace and the military, including Busch, as one of the old political elites who had irresponsibly led them to war without then suitably equipping them to win it. Given this, it was not a shock when the government's orders for the military to intervene against the strikers went unheard.[11] By that point, Waldó Álvarez, the leader of the Federation of Workers of Labor (FOT), had met with both Busch and Toro and secured from them a commitment that the army would not intervene against the protesters.[10]

The peak of the crisis came in May 1936 when the largest strike movement ever seen in the country at that time was called.[11] The culmination of these strikes came on 17 May when, following the occupation of various buildings in La Paz the night before, the military under Busch stepped in and demanded Tejada Sorzano's resignation. A civil-military junta was soon established thereafter with Busch being named provisional president. The same afternoon following the bloodless coup, Busch and Álvarez began negotiations with all of the trade union's demands being met.[11] Busch served as de facto president until David Toro returned from the Chaco on 20 May and was inaugurated on 22 May.

1937 coup

Toro presided over a reformist experiment called Military Socialism (championed by Busch) which allied the military government with labor and leftist movements, for a bit over a year. Soon, however, the Toro regime earned the discontent of the indigenous population and the army. Busch himself felt unsatisfied with Toro's seemingly unending pragmatism and political compromises which to him appeared to be leading nowhere.[12] On 13 July 1937, Busch lead a political movement with the support of military officers and supported by the citizens, achieving the resignation of Toro and installing himself in the Palacio Quemado. Busch assumed the presidency at age 33, the second youngest President of Bolivia after Antonio José de Sucre.

President (1937–1939)

Although Busch was a national hero, his political leanings were unknown to the general population. The left and right alike assumed he would revert from Toro's military socialism to the traditional political establishment Bolivia had seen prior to the Chaco War, a sentiment Busch himself did little to clarify.[12] While showing a tendency for economic conservatism, politically his regime began to adopt more radical elements of Toro's administration.[13]

National Convention of 1938

President Toro had called for a National Convention in 1937 to be held the next year. Following his resignation, Busch organized a new governing board that in March 1938 called for the election of a constituent assembly which was to be held from 23 May to 30 October, and be charged with rewriting the constitution of Bolivia. The convention was the opportunity for new postwar political forces to assert themselves against the traditional prewar Genuine Republican, Liberal, and Socialist Republican parties who, in turn, attempted to reestablish the old order. Soon, labor, veteran, moderate, and even radical leftist movements banded together into an electoral alliance known as the Socialist Single Front which was endorsed by Busch. Faced with this new movement led by Busch, the traditional parties withdrew from the election allowing the so-called Generación del Chaco to win in a landslide and giving them full control over the convention.[14] On 27 May 1938, it elected Busch president with Enrique Baldivieso as vice president. Both were inaugurated the following day as part of a national holiday.[15] In October, the convention successfully produced the Bolivian Constitution of 1938, one of the most important in Bolivian history due to its social character.

Constitutional presidency (1938–1939)

Bogged down for most of his presidency in the procedural aspects of enacting a new political framework (the Assembly, the new Constitution) Busch was not able to pass many meaningful reforms, despite his stated aim of "deepening" the Military Socialism of Toro. Despite continually rising in their power, the fragmented groups of the left remained in constant flux. Parties joined and separated in attempts to form viable coalitions but truly national parties could not arise without firm leadership which could rally support and organization, something Busch demonstrated an inability to do.[16]

Treaty of Peace between Bolivia and Paraguay

On 21 July of 1938, the Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Boundaries between Bolivia and Paraguay was signed in Buenos Aires, bringing a conclusive end to the Chaco War.[17] The treaty, signed by Minister of Foreign Affairs Eduardo Díez de Medina and approved by the National Convention, granted roughly 75% of the Chaco Boreal to Paraguay with the conditions established by the Busch administration, mainly in relation to Bolivia's access to the Paraguay River. The treaty entered into force on 29 August 1938.[18]

Creation of Pando

On 24 September, Busch created the department of Pando separating it from the neighbouring department of Beni and naming it after former President José Manuel Pando who had overseen the Acre War in the region and had toured the entire Amazon. The purpose of the creation of the department was to give greater political hierarchy to the region as well as to achieve the promotion and demographic and economic growth.[19]

Immigration affair

In June 1938, the Busch government had announced open immigration into Bolivia in a sudden reversal of previous government policy. On 9 June, Julio Salmón, minister of agriculture and immigration, announced the end of special restrictions on Jewish migration. While the motive of this likely had to due with the desire to settle Jews in the Chaco before Paraguay did, it nevertheless made Bolivia the only country in the world at the time which permitted unlimited Jewish migration and went against the strong national socialist and pro-German sympathies of the army.

The plan, supported by Moritz Hochschild, known as the "Bolivian Schindler," saw 10,000 European Jews set to migrate to Bolivia within a year.[20] Considering the flood of applications, the desperation of those applying, and the lack of profession and low pay of the diplomatic service, abuses inevitably occurred. A scandal arose when it came to light that the consul general in Paris had required that all visas had to be cleared through the embassy which was charging Jewish emigres between ten and twenty thousand francs for a visa.[21] Though many of the persons involved were dismissed, Busch and his government were faced with charges of gross moral violations and government misconduct by the press.

Dictatorship declared

Faced with the immigration scandal, unhappy with the results produced by his few reforms, and with little support from the fractured left, Busch decided a new direction was needed. To the shock of the nation, Busch, tired of the "political game" and, totally untrained in the art of compromise, declared himself dictator as of 24 April 1939 thus nullifying the very political order he had painstakingly created. The 1938 Constitution, while still in effect, would now be enforced through executive decree as the congress was suspended. In the following months, Germán Busch made the most important changes in his administration. In his four months as dictator, Busch made various attempts to restore the nearly collapsed Bolivian economy by nationalizing the Central Bank of Bolivia and the profits of big mining, and signing into law the first Labor Code of Bolivia; in education, the concept of a unified school was established through a new school code.

However, in the last weeks of his life pressure from the media against his government became more severe. The attacks against his leadership included claims "that he was young and inexperienced to govern" and "that he had neither culture nor knowledge." As a measure of Busch's volcanic, unpredictable nature and distaste for the press, he once had Alcides Arguedas, a respected Bolivian diplomat, politician and writer, brought to his office, where he proceeded to physically slap him for a column critical of his regime.[22] Arguedas was 60 years old at the time and Busch 35. Attacks against him were compounded by the powerful elites and tin barons who started a crusade against Busch, after he launched the decree of 7 June 1939 with the label "Let Bolivia take advantage of its riches," which ordered the delivery of 100% of the miners' currency to the State.

Death and controversy

Apparent suicide

Unable to control events the way he would have liked, and also accompanied by a deep depression possibly worsened by undiagnosed PTSD attributed to his service in the Chaco War, President Busch committed suicide after shooting himself in the right temple in the early hours of 23 August 1939.[23] On the morning of the 23rd, Germán Busch underwent a difficult operation. After nine hours of agony, he died at 2:45 p.m. Though it is suspected by some[24] that he may have been murdered, the explanation of suicide is generally accepted.

The morning newspaper El Diario of 24 August 1939 published the "Exact version of the suicide of Germán Busch, based on the statements of Major Ricardo Goytia, brother-in-law of the president":[1]

"On the night of the 22nd in which they celebrated the birthday of Colonel Eliodoro Carmona (Busch and Goytia's brother-in-law), everything took place in an atmosphere of family cordiality until three in the morning, when the people in attendance had left. It was then that he recalled having left numerous documents on his desk that had to be dispatched and told Carmona and our informant that he wanted to review and sign them. Then, Goytia made him notice that the hour was late and that it would be more convenient for him to go to rest. The president replied, 'Three million Bolivian citizens weigh on my shoulders, I must ensure their well-being and the progress of the country, but in this work misunderstanding, lack of cooperation and the underhanded action of my enemies hinder my work.' [...] At that moment, [...] Goytia noticed that Busch was suffering from one of his nervous breakdowns [...] and saw that he took a pistol from his pants pocket. Then, Goytia took him by the hand and in a fight to prevent him from using it against himself, in which Carmona also participated, the first shot came out of a window. But since the president had extraordinary vigor, he detached himself from both, throwing them away from him, an instant that he took as the opportunity to fire himself the fatal shot in the right storm, immediately falling on the floor of the room."

The morning papers La Calle, El País, La Nación and La Razón replicated the same hypothesis about suicide.

Following the president's death, the more conservative and pro-oligarchic elements in the Bolivian elite reasserted themselves, concluding that reformism had gone entirely too far. Since Busch had proclaimed himself dictator, there was no constitutional succession to speak of, and General Carlos Quintanilla was proclaimed president by the armed forces. Quintanilla was charged with calling new elections and returning matters to the status quo pre-Toro.

Controversy

Luis Toro Ramallo, in his work published in 1940, the year after Busch's death, Busch is dead, who lives now? reported that in those days conjectures about the death of the president circulated throughout the city and that "riots and revolutions were announced."[25] On the other hand, they "murmured" and spoke aloud against the "coup leader" Quintanilla. In order to reinforce the version of Busch's suicide, the government of Quintanilla issued a statement on 24 August which "leaves on record with full evidence that the death of the president is due to an absolutely voluntary act by determination made under the weight of his deep patriotic anguish."

On 28 September, the autopsy report was delivered which concluded "possible suicide." "This cannot be affirmed categorically due to the fact that the traces left by a shot at a short distance [...] are not noticeable because the wound has been washed for healing." Later, the final order of the case, issued on 5 October 1939, concluded that "President Busch has ended his existence through the violent procedure of suicide [...] at his work desk in his private home, using a Colt 32 revolver." This ruling generated debate.

In 1944, Congressman Edmundo Roca and Captain Julio Ponce de León named Colonel Eliodoro Carmona as the "main author of Busch's death" and requested "imprisonment while ordinary justice is pronounced again". In this way, the investigation was reopened. La Calle reported on 31 August 1944 that these accusations were made due to the "statements" made by Carmona in Charagua. Lieutenant Eufracio Bruno, who would later testify at the trial, said that he asked Carmona "Why do public opinion point to you as the author of Busch's death?" and that in a drunken state, he replied "Yes, I killed him, now what do you want?" Bruno also assured that on the birthday of officer Julio Garnica, Carmona confirmed "this arm killed Colonel Busch for eighteen thousand dollars."

The family of Germán Busch's father, Pablo Busch, also support the theory that Busch's death was an assassination by his in-laws in the Carmona family. According to Lila Ávila Busch, Germán Busch's niece, when her grandfather, Pablo Busch, received at his residence in Genoa the telegram informing him of the death of Busch he threw it angrily stating that "This is the work of the Carmona."[26] Herlan Vaca Díez, Busch's nephew, claims that his uncle Gustavo Busch, Germán Busch's brother, spoke with the butler who attended the party during which Busch died. "He always said that Carmona had not only killed Germán, but had also killed another person before." Robert Brockmann pushed against these claims, saying "did Pablo know, thousands of miles away, that the Carmona had murdered Germán? How did he know?" and that "The alluded role of the butler Medina is tenuous at best."[3]

Augusto Céspedes, in his work The Hanging President, stated that "Busch's suicide was so opportune for the large miners that even today it makes us presume a strategic assassination."[27] Nevertheless, contemporary historians such as Robert Brockmann state that the narrative of suicide is the most maintainable.[3] According to Brockmann, "The thorough on-site police investigation, which proves the suicide, is lightly dismissed. In Bolivia, where it is impossible to keep a secret, it would not be feasible to build and maintain such an elaborate lie for almost eight decades." Brockmann also points to the fact that between 1938 and 1939 Busch had attempted to commit suicide at least six times "So when you add up the police records, the testimony of the witnesses you realize that there is a significant tendency for him to commit suicide."[26]

Legacy

Currently Germán Busch is considered one of the most enigmatic, heroic and vibrant characters in the entire republican history of Bolivia. Not only because of his participation in the Chaco War, but also because of his short presidential term where he promulgated very important laws, which in the long term, would generate momentous changes, which many years later would influence the National Revolution of 1952. For this reason, President Germán Busch is one of the most honored Bolivian characters in Bolivia.

Busch's conflict with Bolivia's mining companies and tin barons was frequently referenced by former President Evo Morales in various tweets. In July 2019, Morales tweeted "In his government, the young patriot faced the mining thread and the social elites that kept the country impoverished. Busch was the manager of military socialism that sought to dignify the country."[28]

Colonel Alberto Natusch, who ruled Bolivia for 16 days in November 1979, was Busch's nephew. Germán Busch had four children; three sons, Germán, Orlando, and Waldo, and one daughter, Gloria. She was born in 1940 a year after Busch's death and is 78 as of June 2018.[29][30]

Links to Fascism

Because historically the Bolivian army contained some German advisers and German-trained soldiers, Busch (of part-German ancestry himself) was suspected to have Nazi tendencies; this was reinforced by the fact that one German officer that served in the Bolivian army during the Chaco War (Major Achim R. von Kries) managed to form the Landesgruppe-Bolivie from the NSDAP-OA in La Paz, along with some other German expatriates. It has also been suggested that German management of the air travel services of the time was indicative of Nazi support.[31] However, Busch strongly denied this, claiming that his regime was "uniquely Bolivian." The only known relationship between Busch and the Nazi leaders was a car (a black Mercedes-Benz Cabriolet 770K Series II - W150) sent to him as a present by Adolf Hitler at the beginning of 1939, that Busch never used. In fact, the car remained abandoned in a junkyard until the 1970s, when a private citizen recovered it and restored it. (The car is currently located in San Jose, Costa Rica.)

But there were also incidents such as the execution order for the mining magnate Moritz Hochschild, accused of the trafficking of Bolivian passports within the Jewish community during the Nazi persecutions in Europe. Although it should not be forgotten that Busch himself supported Hoschild's plan to bring 30,000 Jews from Europe to Bolivia. Busch had expected newly immigrated Jews, who often came from European cities, to settle in the countryside as farmers. His disappointment that this did not happen coupled with his animosity towards tin barons like Hochschild are likely the reasons for his ordered execution. Either way, Hochschild would not be shot due to pressure even from Busch's own cabinet ministers.

Busch and the era of military socialism in Bolivia came at at a time before the emergence of anti-fascism and the violent separation of National Socialism and Marxism as a result of World War II.[10] In the Bolivia of the 1930s, the boundaries between the many ideas of socialism (from National Socialism to Left Socialism to moderate Socialism), while present, had not yet clearly distinguished themselves. The same problem would occur in 1946 when the United States would refuse to recognize the government of Gualberto Villarroel due to the alleged fascist sympathies of the Revolutionary Nationalist Movement.

Places and monuments

Various locales in Bolivia were named after him including the Germán Busch Province of the department of Santa Cruz which was created by Law No. 672 of 30 November 1984 during the second government of Hernán Siles Zuazo. Located in the province of the same name, Puerto Busch is a river port that is on the international river Paraguay. Puerto Busch, for many decades, was a port project in oblivion, which regained its prominence as a strategic commercial and export zone after the defeat of Bolivia before Chile in the Maritime Demand at the International Court of The Hague. The port is an alternative to a sovereign outlet to the Atlantic Ocean for Bolivia.

A monument to Germán Busch is located in the Bolivian capital of La Paz.

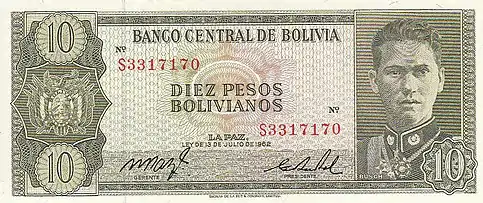

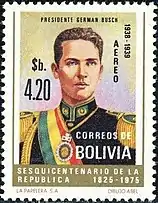

Currency and postage

Bolivian currency reform of 1 January 1963 adopted the peso boliviano which featured Busch on its 10 peso note. However, due to inflation which resulted in the effective devaluation of 95%, the peso was replaced by the Bolivian boliviano effective 1 January 1987. Busch does not appear on contemporary currency.

Busch on the 1963 ten peso bill

Busch on the 1963 ten peso bill Busch on a 1975 postage stamp

Busch on a 1975 postage stamp

See also

References

- "Conmoción y duda: ¿fue la muerte de Germán Busch un suicidio?". www.paginasiete.bo (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- Bailey, Nasatir, pg 639

- "Germán Busch: dónde nació, cómo murió". www.paginasiete.bo (in Spanish). Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- "Busch Putsch". Time Magazine. 8 May 1939. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- Farcau, Bruce W. (1996). The Chaco War: Bolivia and Paraguay, 1932-1935. Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 157. ISBN 0-275-95218-5

- "DECRETO SUPREMO No 28-11-1934 del 28 de Noviembre de 1934 » Derechoteca.com". www.derechoteca.com. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- "DECRETO SUPREMO del 01 de Diciembre de 1934 – 2 » Derechoteca.com". www.derechoteca.com. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Klein, Herbert S. (1 February 1965). "David Toro and the Establishment of "Military Socialism" in Bolivia". Hispanic American Historical Review. 45 (1): 25–52. doi:10.1215/00182168-45.1.25. ISSN 0018-2168.

- Storia contemporanea, Vol. 11: 4-6. Società editrice il Mulino., 1973. P. 837.

- "Rejuvenecer (y salvar) la nación: el socialismo militar boliviano revisitado". web.archive.org. 30 October 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- "La rebelión de mayo del 36". www.paginasiete.bo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Klein 1967, p. 169

- Klein 1967, p. 170

- Klein 1967, pp. 170–171

- "Bolivia: Ley de 27 de mayo de 1938". www.lexivox.org. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- Klein 1967, pp. 175–176

- "Bolivia-Paraguay: Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Boundaries". The American Journal of International Law. 32 (4): 139–141. 1938. doi:10.2307/2213730. ISSN 0002-9300. JSTOR 2213730.

- Mundi, Jus. "Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Boundaries between Bolivia and Paraguay (1938)". jusmundi.com. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- "Creación del Departamento de Pando (24 de septiembre de 1938)". LHistoria (in Spanish). 19 May 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- Cárdenas, José Arturo. "Bolivia's Schindler saved 10 times as many Jews from Holocaust, writer says". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- Klein 1967, pp. 176–177

- "2 DE AGOSTO DE 1938.- AGRESIÓN DEL PRESIDENTE GERMAN BUSCH AL ESCRITOR ALCIDES ARGUEDAS | Historias de Bolivia". 2 DE AGOSTO DE 1938.- AGRESIÓN DEL PRESIDENTE GERMAN BUSCH AL ESCRITOR ALCIDES ARGUEDAS | Historias de Bolivia. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- Newton, Michael (17 April 2014). Famous Assassinations in World History: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 615. ISBN 9781610692861.

- Kurt Riess, Total Espionage, 1941, pp. 247-248

- Ramallo, Luis Toro (1940). Busch ha muerto. Quien vive ahora?: otra página de la historia de Bolivia (in Spanish). Impreso en los talleres de la Editorial Nascimento.

- "Descendientes de Busch, contra el libro de Brockmann | EL DEBER". eldeber.com.bo (in Spanish). Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Céspedes, Augusto (1975). El presidente colgado (in Spanish). Editorial Universitaria de Buenos Aires.

- Morales, Evo (13 July 2019). "Evo Morales Ayma on Twitter". Twitter. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- r.charquina (27 January 2019). "Germán Busch y otras páginas en la historia de Bolivia". Reacción Charquina (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- "Central de Noticias San Xavier". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- No byline (22 July 1941). "Nazi Intrigue in Bolivia". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

Bibliography

- Céspedes, Augusto (1975). El presidente colgado (in Spanish). Editorial Universitaria de Buenos Aires.

- Farcau, Bruce W. "The Chaco War: Bolivia and Paraguay, 1932-1935."

- Klein, Herbert S. (May 1967). "Germán Busch and the Era of "Military Socialism" in Bolivia". The Hispanic American Historical Review. XLVII (2): 166–184.

- Mesa José de; Gisbert, Teresa; and Carlos D. Mesa, "Historia De Bolivia." (in Spanish)

- Miller Bailey, Helen. "Latin America: The Development of Its Civilization" Abraham Phineas Nasatir, Published by Prentice-Hall, 1968

- Querejazu Calvo, Roberto. "Masamaclay." (in Spanish)

- Ramallo, Luis Toro (1940). Busch ha muerto. Quien vive ahora?: otra página de la historia de Bolivia (in Spanish). Impreso en los talleres de la Editorial Nascimento.

- "Busch Putsch". Time Magazine. 8 May 1939. Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- The New West Coast Leader, Published by s.n., Item notes: v.28 no.1429-14541939

External links

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by José Luis Tejada Sorzano |

President of Bolivia De facto 1936 |

Succeeded by David Toro |

| Preceded by David Toro |

President of Bolivia 1937–1939 |

Succeeded by Carlos Quintanilla Interim |