Gigantophis

Gigantophis garstini is an extinct giant snake.[3] Before the Paleocene constrictor genus Titanoboa was described from Colombia in 2009, Gigantophis was regarded as the largest snake ever recorded. Gigantophis lived about 40 million years ago during the Eocene epoch of the Paleogene Period, in the Paratethys Sea, within the northern Sahara, where Egypt[3] and Algeria are now located.

| Gigantophis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | †Madtsoiidae |

| Genus: | †Gigantophis |

| Species: | |

| Binomial name | |

| †Gigantophis garstini[1] C. W. Andrews, 1901[2] | |

Description

Size

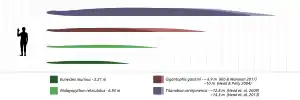

Jason Head, of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, has compared fossil Gigantophis vertebrae to those of the largest modern snakes, and concluded that the extinct snake could grow from 9.3 to 10.7 m (30.5 to 35.1 ft) in length. If 10.7 m (35.1 ft), it would have been more than 10% longer than its largest living relatives.[4][5]

Later estimates, based on allometric equations scaled from the articular processes of tail vertebrae referred to Gigantophis, revised the length of Gigantophis to 6.9 ± 0.3 metres (22.64 ± 0.98 ft).[6]

Discovery

The species is known only from a small number of fossils, mostly vertebrae.

Its discovery was published in 1901 by paleontologist Charles William Andrews, who described it, estimated its length to be about 30 feet, and named it garstini in honor of Sir William Garstin, KCMG, the Under Secretary of State for Public Works in Egypt.[7] In 2013, vertebrae collected in Pakistan were found to be similar to Gigantophis vertebrae collected in Egypt, but their exact affinities are uncertain.[8]

Classification

Gigantophis is classified as a member of the extinct family Madtsoiidae.

References

- "Gigantophis". The Paleobiology Database. Retrieved 2012-07-11.

- "Gigantophis garstini". The Paleobiology Database. Retrieved 2012-07-10.

- Dunham, Will (2009-02-04). "Titanic ancient snake was as long as Tyrannosaurus". Reuters UK. Retrieved 2012-07-10.

- Head, J.; Polly, D. (2004). "They might be giants: morphometric methods for reconstructing body size in the world's largest snakes". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 24 (Supp. 3): 68A–69A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2004.10010643. S2CID 220415208.

- "A giant among snakes". New Scientist (2473). 10 November 2004. p. 17.

- Rio, J.P; Mannion, P.D. (2017). "The osteology of the giant snake Gigantophis garstini from the upper Eocene of North Africa and its bearing on the phylogenetic relationships and biogeography of Madtsoiidae" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 37 (4): e1347179. doi:10.1080/02724634.2017.1347179. S2CID 90335531.

- Andrews, Chas. W. (October 1901). "II.—Preliminary Note on some Recently Discovered Extinct Vertebrates from Egypt. (Part II.)". Geological Magazine. 8 (10): 436–444. Bibcode:1901GeoM....8..436A. doi:10.1017/S0016756800179750.

- Rage, Jean-Claude; Métais, Grégoire; Bartolini, Annachiara; Brohi, Imdad A.; Lashari, Rafiq A.; Marivaux, Laurent; Merle, Didier; Solangi, Sarfraz H. (May 2014). "First report of the giant snake Gigantophis (Madtsoiidae) from the Paleocene of Pakistan: Paleobiogeographic implications". Geobios. 47 (3): 147–153. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2014.03.004.