Gordon Pask

Andrew Gordon Speedie Pask (28 June 1928 – 29 March 1996) was an English author, inventor, educational theorist, cybernetician and psychologist who made significant contributions to cybernetics, instructional psychology, experimental epistemology and educational technology. Pask first learned about cybernetics in the early 1950s when the originator of the subject, Norbert Wiener, spoke at Cambridge University, where Pask was an undergraduate student. Pask was asked to be of assistance during Wiener's talk.[1]

Gordon Pask | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 28 June 1928 |

| Died | 29 March 1996 (aged 67) London |

| Nationality | United Kingdom |

| Alma mater | University of Cambridge University of London Open University |

| Known for | Conversation theory Interactions of actors theory |

| Awards | Wiener Gold Medal (1984) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Cybernetics Psychology |

| Institutions | Brunel University University of Illinois at Chicago University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Concordia University Georgia Institute of Technology |

| Influences | Norbert Wiener |

| Influenced | Ted Nelson, Nicholas Negroponte |

Holding three doctorate degrees, Pask published more than 250 journal articles, books, patents and technical reports from funding from United States Armed Forces, the British Ministry of Defence, the British Home Office and the British Road Research Laboratory.[2] He taught at the University of Illinois, Old Dominion University, Concordia University, Open University, University of New Mexico, Architectural Association School of Architecture and MIT.[3]

Biography

Pask was born in Derby, England, in 1928, and educated at Rydal Penrhos. Before qualifying precociously as a mining engineer at Liverpool Polytechnic, now Liverpool John Moores University, Pask studied geology at Bangor University. He obtained an MA in natural sciences from Cambridge in 1952 and a PhD in psychology from the University of London in 1964. Whilst visiting professor of educational technology, he obtained the first DSc from the Open University and an ScD from his college, Downing Cambridge in 1995. From the 1960s Pask directed commercial research at System Research Ltd in Richmond, Surrey and his partnership, Pask Associates.

Work

Pask's primary contributions to cybernetics, educational psychology, learning theory and systems theory, as well as to numerous other fields, was his emphasis on the personal nature of reality, and on the process of learning as stemming from the consensual agreement of interacting actors in a given environment ("conversation").

His work was complex, extensive, and deeply thought out, at least until late in his life, when he benefited less often from critical feedback of research peers, reviewers of proposals and reports to government bodies in the US and UK, and, perhaps most especially, the tension between experimentation and theoretical stands. His publications, however, represent a storehouse of ideas that are not fully mined.[4]

Pask's most well known work was the development of:

- Conversation theory: is a cybernetic and dialectic framework that offers a scientific theory to explain how interactions lead to "construction of knowledge", or, as Pask preferred "knowing" (wishing to preserve both the dynamic/kinetic quality, and the necessity for there to be a "knower").[5] It came out of his work on instructional design and models of individual learning styles. In regard to learning styles, he identified conditions required for concept sharing and described the learning styles holist, serialist, and their optimal mixture versatile. He proposed a rigorous model of analogy relations.

- Interactions of actors theory: This is a generalised account of the eternal kinetic processes that support kinematic conversations bounded with beginnings and ends in all media. It is reminiscent of Freud's psychodynamics, Bateson's panpsychism (see "Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity" 1980). Pask's nexus of analogy, dependence and mechanical spin produces the differences that are central to cybernetics.

Pask participated in the seminal exhibition "Cybernetic Serendipity" (ICA London, 1968) with the interactive installation "Colloquy of Mobiles", continuing his ongoing dialogue with the visual and performing arts. (cf Rosen 2008, and Dreher's History of Computer Art) Pask influenced such diverse individuals as Ted Nelson, who references Pask in Computer Lib/Dream Machines and whose interest in hypermedia is much like Pask's entailment meshes; and Nicholas Negroponte, whose earliest research efforts at the Architecture Machine Group on "idiosyncratic systems" and software-based partners for design have their roots in Pask's work as a consultant to Negroponte's efforts.

Interactions of actors theory

While working with clients in the last years of his life, Gordon Pask produced an axiomatic scheme[6] for his interactions of actors theory, less well-known than his conversation theory. Interactions of Actors, Theory and Some Applications, as the manuscript is entitled, is essentially a concurrent spin calculus applied to the living environment with strict topological constraints.[7] One of the most notable associates of Gordon Pask, Gerard de Zeeuw, was a key contributor to the development of interactions of actors theory.

Interactions of actors theory is a process theory.[10] As a means to describe the interdisciplinary nature of his work, Pask would make analogies to physical theories in the classic positivist enterprises of the social sciences. Pask sought to apply the axiomatic properties of agreement or epistemological dependence to produce a "sharp-valued" social science with precision comparable to the results of the hard sciences. It was out of this inclination that he would develop his interactions of actors theory. Pask's concepts produce relations in all media and he regarded IA as a process theory. In his complementarity principle he stated "Processes produce products and all products (finite, bounded coherences) are produced by processes".[11]

Most importantly Pask also had his exclusion principle. He proved that no two concepts or products could be the same because of their different histories. He called this the "No Doppelgangers" clause or edict.[10] Later he reflected "Time is incommensurable for Actors".[12] He saw these properties as necessary to produce differentiation and innovation or new coherences in physical nature and, indeed, minds.

In 1995, Pask stated what he called his Last Theorem: "Like concepts repel and unlike concepts attract". For ease of application Pask stated the differences and similarities of descriptions (the products of processes) were context and perspective dependent. In the last three years of his life Pask presented models based on Knot theory knots which described minimal persisting concepts. He interpreted these as acting as computing elements which exert repulsive forces to interact and persist in filling the space. The knots, links and braids of his entailment mesh models of concepts, which could include tangle-like processes seeking "tail-eating" closure, Pask called "tapestries".

His analysis proceeded with like seeming concepts repelling or unfolding but after a sufficient duration of interaction (he called this duration "faith") a pair of similar or like-seeming concepts will always produce a difference and thus an attraction. Amity (availability for interaction), respectability (observability), responsibility (able to respond to stimulus), unity (not uniformity) were necessary properties to produce agreement (or dependence) and agreement-to-disagree (or relative independence) when Actors interact. Concepts could be applied imperatively or permissively when a Petri (see Petri net) condition for synchronous transfer of meaningful information occurred. Extending his physical analogy Pask associated the interactions of thought generation with radiation : "operations generating thoughts and penetrating conceptual boundaries within participants, excite the concepts bounded as oscillators, which, in ridding themselves of this surplus excitation, produce radiation"[13]

In sum, IA supports the earlier kinematic conversation theory work where minimally two concurrent concepts were required to produce a non-trivial third. One distinction separated the similarity and difference of any pair in the minimum triple. However, his formal methods denied the competence of mathematics or digital serial and parallel processes to produce applicable descriptions because of their innate pathologies in locating the infinitesimals of dynamic equilibria (Stafford Beer's "Point of Calm"). He dismissed the digital computer as a kind of kinematic "magic lantern". He saw mechanical models as the future for the concurrent kinetic computers required to describe natural processes. He believed that this implied the need to extend quantum computing to emulate true field concurrency rather than the current von Neumann architecture.

Reviewing IA[12] he said:

Interaction of actors has no specific beginning or end. It goes on forever. Since it does so it has very peculiar properties. Whereas a conversation is mapped (due to a possibility of obtaining a vague kinematic, perhaps picture-frame image, of it, onto Newtonian time, precisely because it has a beginning and end), an interaction, in general, cannot be treated in this manner. Kinematics are inadequate to deal with life: we need kinetics. Even so as in the minimal case of a strict conversation we cannot construct the truth value, metaphor or analogy of A and B. The A, B differences are generalizations about a coalescence of concepts on the part of A and B; their commonality and coherence is the similarity. The difference (reiterated) is the differentiation of A and B (their agreements to disagree, their incoherences). Truth value in this case meaning the coherence between all of the interacting actors.

He added:

It is essential to postulate vectorial times (where components of the vectors are incommensurate) and furthermore times which interact with each other in the manner of Louis Kaufmann's knots and tangles.

In experimental Epistemology Pask, the "philosopher mechanic", produced a tool kit to analyse the basis for knowledge and criticise the teaching and application of knowledge from all fields: the law, social and system sciences to mathematics, physics and biology. In establishing the vacuity of invariance Pask was challenged with the invariance of atomic number. "Ah", he said "the atomic hypothesis". He rejected this instead preferring the infinite nature of the productions of waves.

Pask held that concurrence is a necessary condition for modelling brain functions and he remarked IA was meant to stand AI, Artificial Intelligence, on its head. Pask believed it was the job of cybernetics to compare and contrast. His IA theory showed how to do this. Heinz von Foerster called him a genius,[14] "Mr. Cybernetics", the "cybernetician's cybernetician".

Hewitt's actor model

The Hewitt, Bishop and Steiger approach concerns sequential processing and inter-process communication in digital, serial, kinematic computers. It is a parallel or pseudo-concurrent theory as is the theory of concurrency. See Concurrency. In Pask's true field concurrent theory kinetic processes can interrupt (or, indeed, interact with) each other, simply reproducing or producing a new resultant force within a coherence (of concepts) but without buffering delays or priority.[15]

No Doppelgangers

"There are no Doppelgangers" is a fundamental theorem, edict or clause of cybernetics due to Pask in support of his theories of learning and interaction in all media: conversation theory and interactions of actors theory. It accounts for physical differentiation and is Pask's exclusion principle.[16] It states no two products of concurrent interaction can be the same because of their different dynamic contexts and perspectives. No Doppelgangers is necessary to account for the production by interaction and intermodulation (c.f. beats) of different, evolving, persisting and coherent forms. Two proofs are presented both due to Pask.

Duration proof

Consider a pair of moving, dynamic participants and producing an interaction . Their separation will vary during . The duration of observed from will be different from the duration of observed from .[12][17]

Let and be the start and finish times for the transfer of meaningful information, we can write:

|

TsA ≠ TfB, TsB ≠ TfB, TsA ≠ TsB, |

TfA ≠ TsB TfA ≠ TsA TfA ≠ TfB |

Thus

A ≠ B

Pask remarked:[12]

Conversation is defined as having a beginning and an end and time is vectorial. The components of the vector are commensurable (in duration). On the other hand actor interaction time is vectorial with components that are incommensurable. In the general case there is no well-defined beginning and interaction goes on indefinitely. As a result the time vector has incommensurable components. Both the quantity and quality differ.

No Doppelgangers applies in both the conversation theory's kinematic domain (bounded by beginnings and ends) where times are commensurable and in the eternal kinetic interactions of actors domain where times are incommensurable.

Reproduction proof

The second proof[10] is more reminiscent of R.D. Laing:[18] Your concept of your concept is not my concept of your concept—a reproduced concept is not the same as the original concept. Pask defined concepts as persisting, countably infinite, recursively packed spin processes (like many cored cable, or skins of an onion) in any medium (stars, liquids, gases, solids, machines and, of course, brains) that produce relations.

Here we prove A(T) ≠ B(T).

D means "description of" and <Con A(T), D A(T)> reads A's concept of T produces A's description of T, evoking Dirac notation (required for the production of the quanta of thought: the transfer of "set-theoretic tokens", as Pask puts it in 1996[12]).

- TA = A(T) = <Con A(T), D A(T)>, A's Concept of T,

- TB = B(T) = <Con B(T), D B(T)>, B's Concept of T,

or, in general

- TZ = Z(T) = <Con Z (T), D Z(T)>,

also, in general

- AA = A(A) = <Con A(A), D A(A)>, A's Concept of A,

- AB = A(B) = <Con A(B), D A(B)>, A's Concept of B.

and vice versa, or, in general terms

- ZZ = Z(Z) = <Con Z(Z), D Z>,

given that for all Z and all T, the concepts

- TA = A(T) is not equal to TB = B(T)

and that

AA = A(A) is not equal to BA = B(A) and vice versa, hence, there are no Doppelgangers.

Q.E.D.

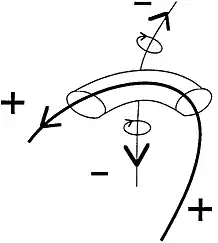

A mechanical model

Pask attached a piece of string to a bar[19] with three knots in it. Then he attached a piece of elastic to the bar with three knots in it. One observing actor, A, on the string would see the knotted intervals on the other actor as varying as the elastic was stretched and relaxed corresponding to the relative motion of B as seen from A. The knots correspond to the beginning of the experiment then the start and finish of the A/B interaction. Referring to the three intervals, where x, y, z, are the separation distances of the knots from the bar and each other, he noted x > y > z on the string for participant A does not imply x > z for participant B on the elastic. A change of separation between A and B producing Doppler shifts during interaction, recoil or the differences in relativistic proper time for A and B, would account for this for example. On occasion a second knotted string was tied to the bar representing coordinate time.

Further context

To set in further context Pask won a prize from Old Dominion University for his complementarity principle: "All processes produce products and all products are produced by processes". This can be written:

Ap(ConZ(T)) => DZ (T) where => means produces and Ap means the "application of", D means "description of" and Z is the concept mesh or coherence of which T is part. This can also be written

- <Ap(ConZ (T)), DZ (T)>.

Pask distinguishes Imperative (written &Ap or IM) from Permissive Application (written Ap)[20] where information is transferred in the Petri net manner, the token appearing as a hole in a torus producing a Klein bottle containing recursively packed concepts.[10]

Pask's "hard" or "repulsive"[10] carapace was a condition he required for the persistence of concepts. He endorsed Nicholas Rescher's coherence theory of truth approach where a set membership criterion of similarity also permitted differences amongst set or coherence members, but he insisted repulsive force was exerted at set and members' coherence boundaries. He said of G. Spencer Brown's Laws of Form that distinctions must exert repulsive forces. This is not yet accepted by Spencer Brown and others. Without a repulsion, or Newtonian reaction at the boundary, sets, their members or interacting participants would diffuse away forming a "smudge"; Hilbertian marks on paper would not be preserved. Pask, the mechanical philosopher, wanted to apply these ideas to bring a new kind of rigour to cybernetic models.

Some followers of Pask emphasise his late work, done in the closing chapter of his life, which is neither as clear nor as grounded as the prior decades of research and machine- and theory-building. This tends to skew the impression gleaned by researchers as to Pask's contribution or even his lucidity.

Publications

Pask wrote several books and more than two hundred journal articles.

Selected books

- 1961, An Approach to Cybernetics. Hutchinson.

- 1975, Conversation, cognition and learning. New York: Elsevier.

- 1975, The Cybernetics of Human Learning and Performance. Hutchinson.

- 1976, Conversation Theory, Applications in Education and Epistemology. Elsevier.

- 1981, Calculator Saturnalia, Or, Travels with a Calculator : A Compendium of Diversions & Improving Exercises for Ladies and Gentlemen with Ranulph Glanville and Mike Robinson. Wildwood.

- 1982, Microman Living and growing with computers. with Susan Curran Macmillan.

- 1993, Interactions of Actors, Theory and Some Applications

- 1996, Heinz von Foerster's Self-Organisation, the Progenitor of Conversation and Interaction Theories

Selected papers

- 1993, Interactions of Actors, Theory and Some Applications, Download incomplete 90-page manuscript of 1993.

- 1996, Heinz von Foerster's Self-Organisation, the Progenitor of Conversation and Interaction Theories, Systems Research (1996) 13, 3, pp. 349–362

Patent

- U.S. Patent 2,984,017 - Apparatus for assisting an operator in performing a skill (1961)

Exhibition

See also

References

- Pickering, Andrew (2009). The Cybernetic Brain: Sketches of Another Future. University of Chicago Press. p. 313. ISBN 978-0226667904.

- Biography at International Federation for Systems Research

- Gordon Pask Bio: Book Chapter

- http://pangaro.com/pask/

- Gordon Pask (1975). The Cybernetics of Human Learning and Performance. Hutchinson.

- Short discussion in context of upper ontology and the inadequacy of serial (digital computer) modelling Retrieved 9 June 2008 at cybsys.co.uk

- Nick Green (2003). Gordon Pask. At cybsoc.org. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- Aspects of these structures can be investigated with Scharein's KnotPlot software.

- Pask (1993) fig.35 para. 219

- Gordon Pask (1993), Interactions of Actors, Theory and Some Applications

- Pask (1996) p.355 and Postulate (20) p. 359

- Gordon Pask (1996). Heinz von Foerster's Self-Organisation, the Progenitor of Conversation and Interaction Theories.

- Pask 1993, paragraph 84.

- von Foerster pp 35–42 in Glanville (1993)

- Pask 1993 paras 100, 130

- Pask (1993) para 82 and Table 4

- Pask (1993) para 102

- R.D. Laing (1970)

- Green, Nick. "On Gordon Pask." Kybernetes 30.5/6 (2001): 673-682.

- Pask (1993) para 188

Further reading

- Bird, J., and Di Paolo, E. A., (2008) Gordon Pask and his maverick machines. In P. Husbands, M. Wheeler, O. Holland (eds), The Mechanical Mind in History, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 185 – 211. ISBN 9780262083775

- Barnes, G. (1994) "Justice, Love and Wisdom" Medicinska Naklada, Zagreb ISBN 953-176-017-9.

- Glanville, R. and Scott, B. (2001). "About Gordon Pask", Special double issue of Kybernetes, Gordon Pask, Remembered and Celebrated, Part I, 30, 5/6, pp. 507–508.

- Green, N. (2004). "Axioms from Interactions of Actors Theory", Kybernetes, 33, 9/10, pp. 1433–1462. Download

- Glanville, R. (ed.) (1993). Gordon Pask—A Festschrift Systems Research, 10, 3.

- Pangaro, P. (1987). An Examination and Confirmation of a Macro Theory of Conversations through a Realization of the Protologic Lp by Microscopic Simulation PhD Thesis Links

- Margit Rosen: "The control of control" – Gordon Pasks kybernetische Ästhetik. In: Ranulph Glanville, Albert Müller (eds.): Pask Present. Cat. of exhib. Atelier Färbergasse, Vienna, 2008, p. 130-191.

- Scott, B. and Glanville G. (eds.) (2001). Special double issue of Kybernetes, Gordon Pask, Remembered and Celebrated, Part I, 30, 5/6.

- Scott, B. and Glanville G. (eds.) (2001). Special double issue of Kybernetes, Gordon Pask, Remembered and Celebrated, Part II, 30, 7/8.

- Scott, B. (ed. and commentary) (2011). "Gordon Pask: The Cybernetics of Self-Organisation, Learning and Evolution Papers 1960–1972" pp 648 Edition Echoraum (2011).

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Gordon Pask |

- Pask: Biography at International Federation for Systems Research

- Biography at George Washington University

- PDFs of Pask's books and key papers at pangaro.com

- Gordon Pask in the MacTutor History of Mathematics archive

- Pask archive

- Conversation theory

- Cybernetics Society biography: The foundations of Conversation Theory: Interactions of Actors Theory (IA)

- QuickTime videos of Dr. Paul Pangaro teaching Cybernetics and Pask's Entailment Meshes at Stanford

- QuickTime clip of Pask on Entailment Meshes

- Pangaro's obituary in London Guardian

- Rocha's obituary for International Journal of General Systems

- Nick Green. (2004). "Axioms from Interactions of Actors Theory" Kybernetes, vol.33, no. 9/10, pp. 1433–1455.

- Thomas Dreher: History of Computer Art, chap. II.3.1.1 Gordon Pask's "Musicolour System", chap. II.3.2.3 Gordon Pask's "Colloquy of Mobiles".

- Assertions and aphorisms of Gordon Pask at The Cybernetics Society