Epistemology

Epistemology (/ɪˌpɪstɪˈmɒlədʒi/ (![]() listen); from Greek ἐπιστήμη, epistēmē 'knowledge', and -logy) is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemologists study the nature of knowledge, epistemic justification, the rationality of belief, and various related issues. Epistemology is considered one of the four main branches of philosophy, along with ethics, logic, and metaphysics.[1]

listen); from Greek ἐπιστήμη, epistēmē 'knowledge', and -logy) is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemologists study the nature of knowledge, epistemic justification, the rationality of belief, and various related issues. Epistemology is considered one of the four main branches of philosophy, along with ethics, logic, and metaphysics.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Epistemology |

|---|

|

Core concepts |

|

Distinctions |

|

Schools of thought |

|

Topics and views |

|

Specialized domains of inquiry |

|

Notable epistemologists |

|

Related fields |

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

Left to right: Plato, Kant, Nietzsche, Buddha, Confucius, Averroes |

| Branches |

| Periods |

| Traditions |

|

Traditions by region Traditions by school Traditions by religion |

| Literature |

|

| Philosophers |

| Lists |

| Miscellaneous |

|

|

Debates in epistemology are generally clustered around four core areas:[2][3][4]

- The philosophical analysis of the nature of knowledge and the conditions required for a belief to constitute knowledge, such as truth and justification

- Potential sources of knowledge and justified belief, such as perception, reason, memory, and testimony

- The structure of a body of knowledge or justified belief, including whether all justified beliefs must be derived from justified foundational beliefs or whether justification requires only a coherent set of beliefs

- Philosophical skepticism, which questions the possibility of knowledge, and related problems, such as whether skepticism poses a threat to our ordinary knowledge claims and whether it is possible to refute skeptical arguments

In these debates and others, epistemology aims to answer questions such as "What do we know?", "What does it mean to say that we know something?", "What makes justified beliefs justified?", and "How do we know that we know?".[1][2][5][6][7]

Background

Etymology

The word epistemology is derived from the ancient Greek epistēmē, meaning "knowledge", and the suffix -logia, meaning "logical discourse" (derived from the Greek word logos meaning "discourse").[8] The word's appearance in English was predated by the German term Wissenschaftslehre (literally, theory of science), which was introduced by philosophers Johann Fichte and Bernard Bolzano in the late 18th century. The word "epistemology" first appeared in 1847, in a review in New York's Eclectic Magazine. It was first used as a translation of the word Wissenschaftslehre as it appears in a philosophical novel by German author Jean Paul:

The title of one of the principal works of Fichte is 'Wissenschaftslehre,' which, after the analogy of technology ... we render epistemology.[9]

The word "epistemology" was properly introduced into Anglophone philosophical literature by Scottish philosopher James Frederick Ferrier in 1854, who used it in his Institutes of Metaphysics:

This section of the science is properly termed the Epistemology—the doctrine or theory of knowing, just as ontology is the science of being... It answers the general question, 'What is knowing and the known?'—or more shortly, 'What is knowledge?'[10]

It is important to note that the French term épistémologie is used with a different and far narrower meaning than the English term "epistemology", being used by French philosophers to refer solely to philosophy of science. For instance, Émile Meyerson opened his Identity and Reality, written in 1908, with the remark that the word 'is becoming current' as equivalent to 'the philosophy of the sciences.'[11]

History of epistemology

The concept of "epistemology" as a distinct field of inquiry predates the introduction of the term into the lexicon of philosophy. John Locke, for instance, described his efforts in Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689) as an inquiry "into the original, certainty, and extent of human knowledge, together with the grounds and degrees of belief, opinion, and assent".[12] According to Brett Warren, the character Epistemon in King James VI of Scotland's Daemonologie (1591) "was meant to be a personification of [what would later come to be] known as 'epistemology': the investigation into the differences of a justified belief versus its opinion."[13]

While it was not until the modern era that epistemology was first recognized as a distinct philosophical discipline which addresses a well-defined set of questions, almost every major historical philosopher has considered questions about what we know and how we know it.[1] Among the Ancient Greek philosophers, Plato distinguished between inquiry regarding what we know and inquiry regarding what exists, particularly in the Republic, the Theaetetus, and the Meno.[1] A number of important epistemological concerns also appeared in the works of Aristotle.[1]

During the subsequent Hellenistic period, philosophical schools began to appear which had a greater focus on epistemological questions, often in the form of philosophical skepticism.[1] For instance, the Pyrrhonian skepticism of Pyrrho and Sextus Empiricus held that eudaimonia (flourishing, happiness, or "the good life") could be attained through the application of epoché (suspension of judgment) regarding all non-evident matters. Pyrrhonism was particularly concerned with undermining the epistemological dogmas of Stoicism and Epicureanism.[1] The other major school of Hellenistic skepticism was Academic skepticism, most notably defended by Carneades and Arcesilaus, which predominated in the Platonic Academy for almost two centuries.[1]

In ancient India the Ajñana school of ancient Indian philosophy promoted skepticism. Ajñana was a Śramaṇa movement and a major rival of early Buddhism, Jainism and the Ājīvika school. They held that it was impossible to obtain knowledge of metaphysical nature or ascertain the truth value of philosophical propositions; and even if knowledge was possible, it was useless and disadvantageous for final salvation. They were specialized in refutation without propagating any positive doctrine of their own.

After the ancient philosophical era but before the modern philosophical era, a number of Medieval philosophers also engaged with epistemological questions at length. Most notable among the Medievals for their contributions to epistemology were Thomas Aquinas, John Duns Scotus, and William of Ockham.[1]

Epistemology largely came to the fore in philosophy during the early modern period, which historians of philosophy traditionally divide up into a dispute between empiricists (including John Locke, David Hume, and George Berkeley) and rationalists (including René Descartes, Baruch Spinoza, and Gottfried Leibniz).[1] The debate between them has often been framed using the question of whether knowledge comes primarily from sensory experience (empiricism), or whether a significant portion of our knowledge is derived entirely from our faculty of reason (rationalism). According to some scholars, this dispute was resolved in the late 18th century by Immanuel Kant, whose transcendental idealism famously made room for the view that "though all our knowledge begins with experience, it by no means follows that all [knowledge] arises out of experience".[14] While the 19th century saw a decline in interest in epistemological issues, it came back to the forefront with the Vienna Circle and the development of analytic philosophy.

There are a number of different methods that scholars use when trying to understand the relationship between historical epistemology and contemporary epistemology. One of the most contentious questions is this: "Should we assume that the problems of epistemology are perennial, and that trying to reconstruct and evaluate Plato's or Hume's or Kant's arguments is meaningful for current debates, too?"[15] Similarly, there is also a question of whether contemporary philosophers should aim to rationally reconstruct and evaluate historical views in epistemology, or to merely describe them.[15] Barry Stroud claims that doing epistemology competently requires the historical study of past attempts to find philosophical understanding of the nature and scope of human knowledge.[16] He argues that since inquiry may progress over time, we may not realize how different the questions that contemporary epistemologists ask are from questions asked at various different points in the history of philosophy.[16]

Central concepts in epistemology

Knowledge

Nearly all debates in epistemology are in some way related to knowledge. Most generally, "knowledge" is a familiarity, awareness, or understanding of someone or something, which might include facts (propositional knowledge), skills (procedural knowledge), or objects (acquaintance knowledge). Philosophers tend to draw an important distinction between three different senses of "knowing" something: "knowing that" (knowing the truth of propositions), "knowing how" (understanding how to perform certain actions), and "knowing by acquaintance" (directly perceiving an object, being familiar with it, or otherwise coming into contact with it).[17] Epistemology is primarily concerned with the first of these forms of knowledge, propositional knowledge. All three senses of "knowing" can be seen in our ordinary use of the word. In mathematics, you can know that 2 + 2 = 4, but there is also knowing how to add two numbers, and knowing a person (e.g., knowing other persons,[18] or knowing oneself), place (e.g., one's hometown), thing (e.g., cars), or activity (e.g., addition). While these distinctions are not explicit in English, they are explicitly made in other languages, including French, Portuguese, Spanish, Romanian, German and Dutch (although some languages related to English have been said to retain these verbs, such as Scots).[note 1] The theoretical interpretation and significance of these linguistic issues remains controversial.

In his paper On Denoting and his later book Problems of Philosophy, Bertrand Russell brought a great deal of attention to the distinction between "knowledge by description" and "knowledge by acquaintance". Gilbert Ryle is similarly credited with bringing more attention to the distinction between knowing how and knowing that in The Concept of Mind. In Personal Knowledge, Michael Polanyi argues for the epistemological relevance of knowledge how and knowledge that; using the example of the act of balance involved in riding a bicycle, he suggests that the theoretical knowledge of the physics involved in maintaining a state of balance cannot substitute for the practical knowledge of how to ride, and that it is important to understand how both are established and grounded. This position is essentially Ryle's, who argued that a failure to acknowledge the distinction between "knowledge that" and "knowledge how" leads to infinite regress.

A priori and a posteriori knowledge

One of the most important distinctions in epistemology is between what can be known a priori (independently of experience) and what can be known a posteriori (through experience). The terms may be roughly defined as follows:[20]

- A priori knowledge is knowledge that is known independently of experience (that is, it is non-empirical, or arrived at before experience, usually by reason). It will henceforth be acquired through anything that is independent from experience.

- A posteriori knowledge is knowledge that is known by experience (that is, it is empirical, or arrived at through experience).

Views that emphasize the importance of a priori knowledge are generally classified as rationalist. Views that emphasize the importance of a posteriori knowledge are generally classified as empiricist.

Belief

One of the core concepts in epistemology is belief. A belief is an attitude that a person holds regarding anything that they take to be true.[21] For instance, to believe that snow is white is comparable to accepting the truth of the proposition "snow is white". Beliefs can be occurrent (e.g. a person actively thinking "snow is white"), or they can be dispositional (e.g. a person who if asked about the color of snow would assert "snow is white"). While there is not universal agreement about the nature of belief, most contemporary philosophers hold the view that a disposition to express belief B qualifies as holding the belief B.[21] There are various different ways that contemporary philosophers have tried to describe beliefs, including as representations of ways that the world could be (Jerry Fodor), as dispositions to act as if certain things are true (Roderick Chisholm), as interpretive schemes for making sense of someone's actions (Daniel Dennett and Donald Davidson), or as mental states that fill a particular function (Hilary Putnam).[21] Some have also attempted to offer significant revisions to our notion of belief, including eliminativists about belief who argue that there is no phenomenon in the natural world which corresponds to our folk psychological concept of belief (Paul Churchland) and formal epistemologists who aim to replace our bivalent notion of belief ("either I have a belief or I don't have a belief") with the more permissive, probabilistic notion of credence ("there is an entire spectrum of degrees of belief, not a simple dichotomy between belief and non-belief").[21][22]

While belief plays a significant role in epistemological debates surrounding knowledge and justification, it also has many other philosophical debates in its own right. Notable debates include: "What is the rational way to revise one's beliefs when presented with various sorts of evidence?"; "Is the content of our beliefs entirely determined by our mental states, or do the relevant facts have any bearing on our beliefs (e.g. if I believe that I'm holding a glass of water, is the non-mental fact that water is H2O part of the content of that belief)?"; "How fine-grained or coarse-grained are our beliefs?"; and "Must it be possible for a belief to be expressible in language, or are there non-linguistic beliefs?"[21]

Truth

Truth is the property or state of being in accordance with facts or reality.[23] On most views, truth is the correspondence of language or thought to a mind-independent world. This is called the correspondence theory of truth. Among philosophers who think that it is possible to analyze the conditions necessary for knowledge, virtually all of them accept that truth is such a condition. There is much less agreement about the extent to which a knower must know why something is true in order to know. On such views, something being known implies that it is true. However, this should not be confused for the more contentious view that one must know that one knows in order to know (the KK principle).[2]

Epistemologists disagree about whether belief is the only truth-bearer. Other common suggestions for things that can bear the property of being true include propositions, sentences, thoughts, utterances, and judgments. Plato, in his Gorgias, argues that belief is the most commonly invoked truth-bearer.[24]

Many of the debates regarding truth are at the crossroads of epistemology and logic.[23] Some contemporary debates regarding truth include: How do we define truth? Is it even possible to give an informative definition of truth? What things are truth-bearers and are therefore capable of being true or false? Are truth and falsity bivalent, or are there other truth values? What are the criteria of truth that allow us to identify it and to distinguish it from falsity? What role does truth play in constituting knowledge? And is truth absolute, or is it merely relative to one's perspective?[23]

Justification

As the term "justification" is used in epistemology, a belief is justified if one has good reason for holding it. Loosely speaking, justification is the reason that someone holds a rationally admissible belief, on the assumption that it is a good reason for holding it. Sources of justification might include perceptual experience (the evidence of the senses), reason, and authoritative testimony, among others. Importantly however, a belief being justified does not guarantee that the belief is true, since a person could be justified in forming beliefs based on very convincing evidence that was nonetheless deceiving.

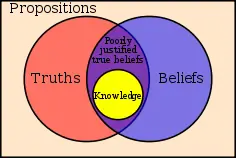

In Plato's Theaetetus, Socrates considers a number of theories as to what knowledge is, first excluding merely true belief as an adequate account. For example, an ill person with no medical training, but with a generally optimistic attitude, might believe that he will recover from his illness quickly. Nevertheless, even if this belief turned out to be true, the patient would not have known that he would get well since his belief lacked justification. The last account that Plato considers is that knowledge is true belief "with an account" that explains or defines it in some way. According to Edmund Gettier, the view that Plato is describing here is that knowledge is justified true belief. The truth of this view would entail that in order to know that a given proposition is true, one must not only believe the relevant true proposition, but must also have a good reason for doing so.[25] One implication of this would be that no one would gain knowledge just by believing something that happened to be true.[26]

Edmund Gettier's famous 1963 paper, "Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?", popularized the claim that the definition of knowledge as justified true belief had been widely accepted throughout the history of philosophy.[27] The extent to which this is true is highly contentious, since Plato himself disavowed the "justified true belief" view at the end of the Theaetetus.[28][1] Regardless of the accuracy of the claim, Gettier's paper produced major widespread discussion which completely reoriented epistemology in the second half of the 20th century, with a newfound focus on trying to provide an airtight definition of knowledge by adjusting or replacing the "justified true belief" view.[note 2] Today there is still little consensus about whether any set of conditions succeeds in providing a set of necessary and sufficient conditions for knowledge, and many contemporary epistemologists have come to the conclusion that no such exception-free definition is possible.[28] However, even if justification fails as a condition for knowledge as some philosophers claim, the question of whether or not a person has good reasons for holding a particular belief in a particular set of circumstances remains a topic of interest to contemporary epistemology, and is unavoidably linked to questions about rationality.[28]

Internalism and externalism

A central debate about the nature of justification is a debate between epistemological externalists on the one hand, and epistemological internalists on the other. While epistemic externalism first arose in attempts to overcome the Gettier problem, it has flourished in the time since as an alternative way of conceiving of epistemic justification. The initial development of epistemic externalism is often attributed to Alvin Goldman, although numerous other philosophers have worked on the topic in the time since.[28]

Externalists hold that factors deemed "external", meaning outside of the psychological states of those who gain knowledge, can be conditions of justification. For example, an externalist response to the Gettier problem is to say that for a justified true belief to count as knowledge, there must be a link or dependency between the belief and the state of the external world. Usually this is understood to be a causal link. Such causation, to the extent that it is "outside" the mind, would count as an external, knowledge-yielding condition. Internalists, on the other hand, assert that all knowledge-yielding conditions are within the psychological states of those who gain knowledge.

Though unfamiliar with the internalist/externalist debate himself, many point to René Descartes as an early example of the internalist path to justification. He wrote that, because the only method by which we perceive the external world is through our senses, and that, because the senses are not infallible, we should not consider our concept of knowledge infallible. The only way to find anything that could be described as "indubitably true", he advocates, would be to see things "clearly and distinctly".[29] He argued that if there is an omnipotent, good being who made the world, then it's reasonable to believe that people are made with the ability to know. However, this does not mean that man's ability to know is perfect. God gave man the ability to know but not with omniscience. Descartes said that man must use his capacities for knowledge correctly and carefully through methodological doubt.[30]

The dictum "Cogito ergo sum" (I think, therefore I am) is also commonly associated with Descartes' theory. In his own methodological doubt—doubting everything he previously knew so he could start from a blank slate—the first thing that he could not logically bring himself to doubt was his own existence: "I do not exist" would be a contradiction in terms. The act of saying that one does not exist assumes that someone must be making the statement in the first place. Descartes could doubt his senses, his body, and the world around him—but he could not deny his own existence, because he was able to doubt and must exist to manifest that doubt. Even if some "evil genius" were deceiving him, he would have to exist to be deceived. This one sure point provided him with what he called his Archimedean point, in order to further develop his foundation for knowledge. Simply put, Descartes' epistemological justification depended on his indubitable belief in his own existence and his clear and distinct knowledge of God.[31]

Defining knowledge

The Gettier problem

Edmund Gettier is best known for his 1963 paper entitled "Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?", which called into question the common conception of knowledge as justified true belief.[32] In just two and a half pages, Gettier argued that there are situations in which one's belief may be justified and true, yet fail to count as knowledge. That is, Gettier contended that while justified belief in a true proposition is necessary for that proposition to be known, it is not sufficient.

According to Gettier, there are certain circumstances in which one does not have knowledge, even when all of the above conditions are met. Gettier proposed two thought experiments, which have become known as Gettier cases, as counterexamples to the classical account of knowledge.[28] One of the cases involves two men, Smith and Jones, who are awaiting the results of their applications for the same job. Each man has ten coins in his pocket. Smith has excellent reasons to believe that Jones will get the job (the head of the company told him); and furthermore, Smith knows that Jones has ten coins in his pocket (he recently counted them). From this Smith infers: "The man who will get the job has ten coins in his pocket." However, Smith is unaware that he also has ten coins in his own pocket. Furthermore, it turns out that Smith, not Jones, is going to get the job. While Smith has strong evidence to believe that Jones will get the job, he is wrong. Smith therefore has a justified true belief that the man who will get the job has ten coins in his pocket; however, according to Gettier, Smith does not know that the man who will get the job has ten coins in his pocket, because Smith's belief is "...true by virtue of the number of coins in Jones's pocket, while Smith does not know how many coins are in Smith's pocket, and bases his belief... on a count of the coins in Jones's pocket, whom he falsely believes to be the man who will get the job."[32]:122 These cases fail to be knowledge because the subject's belief is justified, but only happens to be true by virtue of luck. In other words, he made the correct choice (believing that the man who will get the job has ten coins in his pocket) for the wrong reasons. Gettier then goes on to offer a second similar case, providing the means by which the specifics of his examples can be generalized into a broader problem for defining knowledge in terms of justified true belief.

There have been various notable responses to the Gettier problem. Typically, they have involved substantial attempts to provide a new definition of knowledge that is not susceptible to Gettier-style objections, either by providing an additional fourth condition that justified true beliefs must meet to constitute knowledge, or proposing a completely new set of necessary and sufficient conditions for knowledge. While there have been far too many published responses for all of them to be mentioned, some of the most notable responses are discussed below.

"No false premises" response

One of the earliest suggested replies to Gettier, and perhaps the most intuitive ways to respond to the Gettier problem, is the "no false premises" response, sometimes also called the "no false lemmas" response. Most notably, this reply was defended by David Malet Armstrong in his 1973 book, Belief, Truth, and Knowledge.[33] The basic form of the response is to assert that the person who holds the justified true belief (for instance, Smith in Gettier's first case) made the mistake of inferring a true belief (e.g. "The person who will get the job has ten coins in his pocket") from a false belief (e.g. "Jones will get the job"). Proponents of this response therefore propose that we add a fourth necessary and sufficient condition for knowledge, namely, "the justified true belief must not have been inferred from a false belief".

This reply to the Gettier problem is simple, direct, and appears to isolate what goes wrong in forming the relevant beliefs in Gettier cases. However, the general consensus is that it fails.[28] This is because while the original formulation by Gettier includes a person who infers a true belief from a false belief, there are many alternate formulations in which this is not the case. Take, for instance, a case where an observer sees what appears to be a dog walking through a park and forms the belief "There is a dog in the park". In fact, it turns out that the observer is not looking at a dog at all, but rather a very lifelike robotic facsimile of a dog. However, unbeknownst to the observer, there is in fact a dog in the park, albeit one standing behind the robotic facsimile of a dog. Since the belief "There is a dog in the park" does not involve a faulty inference, but is instead formed as the result of misleading perceptual information, there is no inference made from a false premise. It therefore seems that while the observer does in fact have a true belief that her perceptual experience provides justification for holding, she does not actually know that there is a dog in the park. Instead, she just seems to have formed a "lucky" justified true belief.[28]

Reliabilist response

Reliabilism has been a significant line of response to the Gettier problem among philosophers, originating with work by Alvin Goldman in the 1960s. According to reliabilism, a belief is justified (or otherwise supported in such a way as to count towards knowledge) only if it is produced by processes that typically yield a sufficiently high ratio of true to false beliefs. In other words, this theory states that a true belief counts as knowledge only if it is produced by a reliable belief-forming process. Examples of reliable processes include standard perceptual processes, remembering, good reasoning, and introspection.[34]

One commonly discussed challenge for reliabilism is the case of Henry and the barn façades.[28] In this thought experiment, a man, Henry, is driving along and sees a number of buildings that resemble barns. Based on his perception of one of these, he concludes that he is looking at a barn. While he is indeed looking at a barn, it turns out that all of the other barn-like buildings he saw were façades. According to the challenge, Henry does not know that he has seen a barn, despite his belief being true, and despite his belief having been formed on the basis of a reliable process (i.e. his vision), since he only acquired his reliably formed true belief by accident.[35] In other words, since he could have just as easily been looking at a barn façade and formed a false belief, the reliability of perception in general does not mean that his belief wasn't merely formed luckily, and this luck seems to preclude him from knowledge.[28]

Infallibilist response

One less common response to the Gettier problem is defended by Richard Kirkham, who has argued that the only definition of knowledge that could ever be immune to all counterexamples is the infallibilist definition.[36] To qualify as an item of knowledge, goes the theory, a belief must not only be true and justified, the justification of the belief must necessitate its truth. In other words, the justification for the belief must be infallible.

While infallibilism is indeed an internally coherent response to the Gettier problem, it is incompatible with our everyday knowledge ascriptions. For instance, as the Cartesian skeptic will point out, all of my perceptual experiences are compatible with a skeptical scenario in which I am completely deceived about the existence of the external world, in which case most (if not all) of my beliefs would be false.[30][37] The typical conclusion to draw from this is that it is possible to doubt most (if not all) of my everyday beliefs, meaning that if I am indeed justified in holding those beliefs, that justification is not infallible. For the justification to be infallable, my reasons for holding my everyday beliefs would need to completely exclude the possibility that those beliefs were false. Consequently, if a belief must be infallibly justified in order to constitute knowledge, then it must be the case that we are mistaken in most (if not all) instances in which we claim to have knowledge in everyday situations.[38] While it is indeed possible to bite the bullet and accept this conclusion, most philosophers find it implausible to suggest that we know nothing or almost nothing, and therefore reject the infallibilist response as collapsing into radical skepticism.[37]

Indefeasibility condition

Another possible candidate for the fourth condition of knowledge is indefeasibility. Defeasibility theory maintains that there should be no overriding or defeating truths for the reasons that justify one's belief. For example, suppose that person S believes he saw Tom Grabit steal a book from the library and uses this to justify the claim that Tom Grabit stole a book from the library. A possible defeater or overriding proposition for such a claim could be a true proposition like, "Tom Grabit's identical twin Sam is currently in the same town as Tom." When no defeaters of one's justification exist, a subject would be epistemologically justified.

In a similar vein, the Indian philosopher B.K. Matilal drew on the Navya-Nyāya fallibilist tradition to respond to the Gettier problem. Nyaya theory distinguishes between know p and know that one knows p—these are different events, with different causal conditions. The second level is a sort of implicit inference that usually follows immediately the episode of knowing p (knowledge simpliciter). The Gettier case is examined by referring to a view of Gangesha Upadhyaya (late 12th century), who takes any true belief to be knowledge; thus a true belief acquired through a wrong route may just be regarded as knowledge simpliciter on this view. The question of justification arises only at the second level, when one considers the knowledge-hood of the acquired belief. Initially, there is lack of uncertainty, so it becomes a true belief. But at the very next moment, when the hearer is about to embark upon the venture of knowing whether he knows p, doubts may arise. "If, in some Gettier-like cases, I am wrong in my inference about the knowledge-hood of the given occurrent belief (for the evidence may be pseudo-evidence), then I am mistaken about the truth of my belief—and this is in accordance with Nyaya fallibilism: not all knowledge-claims can be sustained."[39]

Tracking condition

Robert Nozick has offered a definition of knowledge according to which S knows that P if and only if:

- P is true;

- S believes that P;

- if P were false, S would not believe that P;

- if P were true, S would believe that P.[40]

Nozick argues that the third of these conditions serves to address cases of the sort described by Gettier. Nozick further claims this condition addresses a case of the sort described by D.M. Armstrong:[41] A father believes his daughter is innocent of committing a particular crime, both because of faith in his baby girl and (now) because he has seen presented in the courtroom a conclusive demonstration of his daughter's innocence. His belief via the method of the courtroom satisfies the four subjunctive conditions, but his faith-based belief does not. If his daughter were guilty, he would still believe her innocence, on the basis of faith in his daughter; this would violate the third condition.

The British philosopher Simon Blackburn has criticized this formulation by suggesting that we do not want to accept as knowledge beliefs which, while they "track the truth" (as Nozick's account requires), are not held for appropriate reasons. He says that "we do not want to award the title of knowing something to someone who is only meeting the conditions through a defect, flaw, or failure, compared with someone else who is not meeting the conditions."[42] In addition to this, externalist accounts of knowledge, such as Nozick's, are often forced to reject closure in cases where it is intuitively valid.

An account similar to Nozick's has also been offered by Fred Dretske, although his view focuses more on relevant alternatives that might have obtained if things had turned out differently. Views of both the Nozick variety and the Dretske variety have faced serious problems suggested by Saul Kripke.[28]

Knowledge-first response

Timothy Williamson has advanced a theory of knowledge according to which knowledge is not justified true belief plus some extra conditions, but primary. In his book Knowledge and its Limits, Williamson argues that the concept of knowledge cannot be broken down into a set of other concepts through analysis—instead, it is sui generis. Thus, according to Williamson, justification, truth, and belief are necessary but not sufficient for knowledge. Williamson is also known for being one of the only philosophers who take knowledge to be a mental state;[43] most epistemologists assert that belief (as opposed to knowledge) is a mental state. As such, Williamson's claim has been seen to be highly counterintuitive.[44]

Causal theory and naturalized epistemology

In an earlier paper that predates his development of reliabilism, Alvin Goldman writes in his "Causal Theory of Knowing" that knowledge requires a causal link between the truth of a proposition and the belief in that proposition. A similar view has also been defended by Hilary Kornblith in Knowledge and its Place in Nature, although his view is meant to capture an empirical scientific conception of knowledge, not an analysis of the everyday concept "knowledge".[45] Kornblith, in turn, takes himself to be elaborating on the naturalized epistemology framework first suggested by W.V.O. Quine.

The value problem

We generally assume that knowledge is more valuable than mere true belief. If so, what is the explanation? A formulation of the value problem in epistemology first occurs in Plato's Meno. Socrates points out to Meno that a man who knew the way to Larissa could lead others there correctly. But so, too, could a man who had true beliefs about how to get there, even if he had not gone there or had any knowledge of Larissa. Socrates says that it seems that both knowledge and true opinion can guide action. Meno then wonders why knowledge is valued more than true belief and why knowledge and true belief are different. Socrates responds that knowledge is more valuable than mere true belief because it is tethered or justified. Justification, or working out the reason for a true belief, locks down true belief.[46]

The problem is to identify what (if anything) makes knowledge more valuable than mere true belief, or that makes knowledge more valuable than a mere minimal conjunction of its components, such as justification, safety, sensitivity, statistical likelihood, and anti-Gettier conditions, on a particular analysis of knowledge that conceives of knowledge as divided into components (to which knowledge-first epistemological theories, which posit knowledge as fundamental, are notable exceptions).[47] The value problem re-emerged in the philosophical literature on epistemology in the twenty-first century following the rise of virtue epistemology in the 1980s, partly because of the obvious link to the concept of value in ethics.[48]

Virtue epistemology

In contemporary philosophy, epistemologists including Ernest Sosa, John Greco, Jonathan Kvanvig,[49] Linda Zagzebski, and Duncan Pritchard have defended virtue epistemology as a solution to the value problem. They argue that epistemology should also evaluate the "properties" of people as epistemic agents (i.e. intellectual virtues), rather than merely the properties of propositions and propositional mental attitudes.

The value problem has been presented as an argument against epistemic reliabilism by Linda Zagzebski, Wayne Riggs, and Richard Swinburne, among others. Zagzebski analogizes the value of knowledge to the value of espresso produced by an espresso maker: "The liquid in this cup is not improved by the fact that it comes from a reliable espresso maker. If the espresso tastes good, it makes no difference if it comes from an unreliable machine."[50] For Zagzebski, the value of knowledge deflates to the value of mere true belief. She assumes that reliability in itself has no value or disvalue, but Goldman and Olsson disagree. They point out that Zagzebski's conclusion rests on the assumption of veritism: all that matters is the acquisition of true belief.[51] To the contrary, they argue that a reliable process for acquiring a true belief adds value to the mere true belief by making it more likely that future beliefs of a similar kind will be true. By analogy, having a reliable espresso maker that produced a good cup of espresso would be more valuable than having an unreliable one that luckily produced a good cup because the reliable one would more likely produce good future cups compared to the unreliable one.

The value problem is important to assessing the adequacy of theories of knowledge that conceive of knowledge as consisting of true belief and other components. According to Kvanvig, an adequate account of knowledge should resist counterexamples and allow an explanation of the value of knowledge over mere true belief. Should a theory of knowledge fail to do so, it would prove inadequate.[52]

One of the more influential responses to the problem is that knowledge is not particularly valuable and is not what ought to be the main focus of epistemology. Instead, epistemologists ought to focus on other mental states, such as understanding.[53] Advocates of virtue epistemology have argued that the value of knowledge comes from an internal relationship between the knower and the mental state of believing.[47]

Acquiring knowledge

Sources of knowledge

There are many proposed sources of knowledge and justified belief which we take to be actual sources of knowledge in our everyday lives. Some of the most commonly discussed include perception, reason, memory, and testimony.[3][6]

A priori–a posteriori distinction

As mentioned above, epistemologists draw a distinction between what can be known a priori (independently of experience) and what can only be known a posteriori (through experience). Much of what we call a priori knowledge is thought to be attained through reason alone, as featured prominently in rationalism. This might also include a non-rational faculty of intuition, as defended by proponents of innatism. In contrast, a posteriori knowledge is derived entirely through experience or as a result of experience, as emphasized in empiricism. This also includes cases where knowledge can be traced back to an earlier experience, as in memory or testimony.[20]

A way to look at the difference between the two is through an example. Bruce Russell gives two propositions in which the reader decides which one he believes more. Option A: All crows are birds. Option B: All crows are black. If you believe option A, then you are a priori justified in believing it because you don't have to see a crow to know it's a bird. If you believe in option B, then you are posteriori justified to believe it because you have seen many crows therefore knowing they are black. He goes on to say that it doesn't matter if the statement is true or not, only that if you believe in one or the other that matters.[20]

The idea of a priori knowledge is that it is based on intuition or rational insights. Laurence BonJour says in his article "The Structure of Empirical Knowledge",[54] that a "rational insight is an immediate, non-inferential grasp, apprehension or 'seeing' that some proposition is necessarily true." (3) Going back to the crow example, by Laurence BonJour's definition the reason you would believe in option A is because you have an immediate knowledge that a crow is a bird, without ever experiencing one.

Evolutionary psychology takes a novel approach to the problem. It says that there is an innate predisposition for certain types of learning. "Only small parts of the brain resemble a tabula rasa; this is true even for human beings. The remainder is more like an exposed negative waiting to be dipped into a developer fluid".[55]

Analytic–synthetic distinction

.jpg.webp)

Immanuel Kant, in his Critique of Pure Reason, drew a distinction between "analytic" and "synthetic" propositions. He contended that some propositions are such that we can know they are true just by understanding their meaning. For example, consider, "My father's brother is my uncle." We can know it is true solely by virtue of our understanding in what its terms mean. Philosophers call such propositions "analytic". Synthetic propositions, on the other hand, have distinct subjects and predicates. An example would be, "My father's brother has black hair." Kant stated that all mathematical and scientific statements are analytic priori propositions because they are necessarily true but our knowledge about the attributes of the mathematical or physical subjects we can only get by logical inference.

While this distinction is first and foremost about meaning and is therefore most relevant to the philosophy of language, the distinction has significant epistemological consequences, seen most prominently in the works of the logical positivists.[56] In particular, if the set of propositions which can only be known a posteriori is coextensive with the set of propositions which are synthetically true, and if the set of propositions which can be known a priori is coextensive with the set of propositions which are analytically true (or in other words, which are true by definition), then there can only be two kinds of successful inquiry: Logico-mathematical inquiry, which investigates what is true by definition, and empirical inquiry, which investigates what is true in the world. Most notably, this would exclude the possibility that branches of philosophy like metaphysics could ever provide informative accounts of what actually exists.[20][56]

The American philosopher Willard Van Orman Quine, in his paper "Two Dogmas of Empiricism", famously challenged the analytic-synthetic distinction, arguing that the boundary between the two is too blurry to provide a clear division between propositions that are true by definition and propositions that are not. While some contemporary philosophers take themselves to have offered more sustainable accounts of the distinction that are not vulnerable to Quine's objections, there is no consensus about whether or not these succeed.[57]

Science as knowledge acquisition

Science is often considered to be a refined, formalized, systematic, institutionalized form of the pursuit and acquisition of empirical knowledge. As such, the philosophy of science may be viewed variously as an application of the principles of epistemology or as a foundation for epistemological inquiry.

The regress problem

The regress problem (also known as Agrippa's Trilemma) is the problem of providing a complete logical foundation for human knowledge. The traditional way of supporting a rational argument is to appeal to other rational arguments, typically using chains of reason and rules of logic. A classic example that goes back to Aristotle is deducing that Socrates is mortal. We have a logical rule that says All humans are mortal and an assertion that Socrates is human and we deduce that Socrates is mortal. In this example how do we know that Socrates is human? Presumably we apply other rules such as: All born from human females are human. Which then leaves open the question how do we know that all born from humans are human? This is the regress problem: how can we eventually terminate a logical argument with some statements that do not require further justification but can still be considered rational and justified? As John Pollock stated:

... to justify a belief one must appeal to a further justified belief. This means that one of two things can be the case. Either there are some beliefs that we can be justified for holding, without being able to justify them on the basis of any other belief, or else for each justified belief there is an infinite regress of (potential) justification [the nebula theory]. On this theory there is no rock bottom of justification. Justification just meanders in and out through our network of beliefs, stopping nowhere.[58]

The apparent impossibility of completing an infinite chain of reasoning is thought by some to support skepticism. It is also the impetus for Descartes' famous dictum: I think, therefore I am. Descartes was looking for some logical statement that could be true without appeal to other statements.

Responses to the regress problem

Many epistemologists studying justification have attempted to argue for various types of chains of reasoning that can escape the regress problem.

Foundationalism

Foundationalists respond to the regress problem by asserting that certain "foundations" or "basic beliefs" support other beliefs but do not themselves require justification from other beliefs. These beliefs might be justified because they are self-evident, infallible, or derive from reliable cognitive mechanisms. Perception, memory, and a priori intuition are often considered possible examples of basic beliefs.

The chief criticism of foundationalism is that if a belief is not supported by other beliefs, accepting it may be arbitrary or unjustified.[59]

Coherentism

Another response to the regress problem is coherentism, which is the rejection of the assumption that the regress proceeds according to a pattern of linear justification. To avoid the charge of circularity, coherentists hold that an individual belief is justified circularly by the way it fits together (coheres) with the rest of the belief system of which it is a part. This theory has the advantage of avoiding the infinite regress without claiming special, possibly arbitrary status for some particular class of beliefs. Yet, since a system can be coherent while also being wrong, coherentists face the difficulty of ensuring that the whole system corresponds to reality. Additionally, most logicians agree that any argument that is circular is, at best, only trivially valid. That is, to be illuminating, arguments must operate with information from multiple premises, not simply conclude by reiterating a premise.

Nigel Warburton writes in Thinking from A to Z that "[c]ircular arguments are not invalid; in other words, from a logical point of view there is nothing intrinsically wrong with them. However, they are, when viciously circular, spectacularly uninformative."[60]

Infinitism

An alternative resolution to the regress problem is known as "infinitism". Infinitists take the infinite series to be merely potential, in the sense that an individual may have indefinitely many reasons available to them, without having consciously thought through all of these reasons when the need arises. This position is motivated in part by the desire to avoid what is seen as the arbitrariness and circularity of its chief competitors, foundationalism and coherentism. The most prominent defense of infinitism has been given by Peter Klein.[61]

Foundherentism

An intermediate position, known as "foundherentism", is advanced by Susan Haack. Foundherentism is meant to unify foundationalism and coherentism. Haack explains the view by using a crossword puzzle as an analogy. Whereas, for example, infinitists regard the regress of reasons as taking the form of a single line that continues indefinitely, Haack has argued that chains of properly justified beliefs look more like a crossword puzzle, with various different lines mutually supporting each other.[62] Thus, Haack's view leaves room for both chains of beliefs that are "vertical" (terminating in foundational beliefs) and chains that are "horizontal" (deriving their justification from coherence with beliefs that are also members of foundationalist chains of belief).

Philosophical skepticism

Epistemic skepticism questions whether knowledge is possible at all. Generally speaking, skeptics argue that knowledge requires certainty, and that most or all of our beliefs are fallible (meaning that our grounds for holding them always, or almost always, fall short of certainty), which would together entail that knowledge is always or almost always impossible for us.[63] Characterizing knowledge as strong or weak is dependent on a person's viewpoint and their characterization of knowledge.[63] Much of modern epistemology is derived from attempts to better understand and address philosophical skepticism.[64]

Pyrrhonism

One of the oldest forms of epistemic skepticism can be found in Agrippa's trilemma (named after the Pyrrhonist philosopher Agrippa the Skeptic) which demonstrates that certainty can not be achieved with regard to beliefs.[65] Pyrrhonism dates back to Pyrrho of Elis from the 4th century BCE, although most of what we know about Pyrrhonism today is from the surviving works of Sextus Empiricus.[65] Pyrrhonists claim that for any argument for a non-evident proposition, an equally convincing argument for a contradictory proposition can be produced. Pyrrhonists do not dogmatically deny the possibility of knowledge, but instead point out that beliefs about non-evident matters cannot be substantiated.

Cartesian skepticism

The Cartesian evil demon problem, first raised by René Descartes,[note 3] supposes that our sensory impressions may be controlled by some external power rather than the result of ordinary veridical perception.[66] In such a scenario, nothing we sense would actually exist, but would instead be mere illusion. As a result, we would never be able to know anything about the world, since we would be systematically deceived about everything. The conclusion often drawn from evil demon skepticism is that even if we are not completely deceived, all of the information provided by our senses is still compatible with skeptical scenarios in which we are completely deceived, and that we must therefore either be able to exclude the possibility of deception or else must deny the possibility of infallible knowledge (that is, knowledge which is completely certain) beyond our immediate sensory impressions.[67] While the view that no beliefs are beyond doubt other than our immediate sensory impressions is often ascribed to Descartes, he in fact thought that we can exclude the possibility that we are systematically deceived, although his reasons for thinking this are based on a highly contentious ontological argument for the existence of a benevolent God who would not allow such deception to occur.[66]

Responses to philosophical skepticism

Epistemological skepticism can be classified as either "mitigated" or "unmitigated" skepticism. Mitigated skepticism rejects "strong" or "strict" knowledge claims but does approve weaker ones, which can be considered "virtual knowledge", but only with regard to justified beliefs. Unmitigated skepticism rejects claims of both virtual and strong knowledge.[63] Characterizing knowledge as strong, weak, virtual or genuine can be determined differently depending on a person's viewpoint as well as their characterization of knowledge.[63] Some of the most notable attempts to respond to unmitigated skepticism include direct realism, disjunctivism, common sense philosophy, pragmatism, fideism, and fictionalism.[68]

Schools of thought in epistemology

Empiricism

Empiricism is a view in the theory of knowledge which focuses on the role of experience, especially experience based on perceptual observations by the senses, in the generation of knowledge.[69] Certain forms exempt disciplines such as mathematics and logic from these requirements.[70]

There are many variants of empiricism, including British empiricism, logical empiricism, phenomenalism, and some versions of common sense philosophy. Most forms of empiricism give epistemologically privileged status to sensory impressions or sense data, although this plays out very differently in different cases. Some of the most famous historical empiricists include John Locke, David Hume, George Berkeley, Francis Bacon, John Stuart Mill, Rudolf Carnap, and Bertrand Russell.

Rationalism

Rationalism is the epistemological view that reason is the chief source of knowledge and the main determinant of what constitutes knowledge. More broadly, it can also refer to any view which appeals to reason as a source of knowledge or justification. Rationalism is one of the two classical views in epistemology, the other being empiricism. Rationalists claim that the mind, through the use of reason, can directly grasp certain truths in various domains, including logic, mathematics, ethics, and metaphysics. Rationalist views can range from modest views in mathematics and logic (such as that of Gottlob Frege) to ambitious metaphysical systems (such as that of Baruch Spinoza).

Some of the most famous rationalists include Plato, René Descartes, Baruch Spinoza, and Gottfried Leibniz.

Skepticism

Skepticism is a position that questions the possibility of human knowledge, either in particular domains or on a general level.[64] Skepticism does not refer to any one specific school of philosophy, but is rather a thread that runs through many epistemological debates. Ancient Greek skepticism began during the Hellenistic period in philosophy, which featured both Pyrrhonism (notably defended by Pyrrho and Sextus Empiricus) and Academic skepticism (notably defended by Arcesilaus and Carneades). Among ancient Indian philosophers, skepticism was notably defended by the Ajñana school and in the Buddhist Madhyamika tradition. In modern philosophy, René Descartes' famous inquiry into mind and body began as an exercise in skepticism, in which he started by trying to doubt all purported cases of knowledge in order to search for something that was known with absolute certainty.[71]

Pragmatism

Pragmatism is an empiricist epistemology formulated by Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, and John Dewey, which understands truth as that which is practically applicable in the world. Pragmatists often treat "truth" as the final outcome of ideal scientific inquiry, meaning that something cannot be true unless it is potentially observable.[note 4] Peirce formulates the maxim: 'Consider what effects, that might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then, our conception of these effects is the whole of our conception of the object.'[72] This suggests that we are to analyse ideas and objects in the world for their practical value. This is in contrast to any correspondence theory of truth that holds that what is true is what corresponds to an external reality. William James suggests that through a pragmatist epistemology, theories "become instruments, not answers to enigmas in which we can rest."[73]

Contemporary versions of pragmatism have been most notably developed by Richard Rorty and Hilary Putnam. Rorty proposed that values were historically contingent and dependent upon their utility within a given historical period,[74] Contemporary philosophers working in pragmatism are called neopragmatists, and also include Nicholas Rescher, Robert Brandom, Susan Haack, and Cornel West.

Naturalized epistemology

In certain respects an intellectual descendant of pragmatism, naturalized epistemology considers the evolutionary role of knowledge for agents living and evolving in the world.[75] It de-emphasizes the questions around justification and truth, and instead asks, empirically, how reliable beliefs are formed and the role that evolution played in the development of such processes. It suggests a more empirical approach to the subject as a whole, leaving behind philosophical definitions and consistency arguments, and instead using psychological methods to study and understand how "knowledge" is actually formed and is used in the natural world. As such, it does not attempt to answer the analytic questions of traditional epistemology, but rather replace them with new empirical ones.[76]

Naturalized epistemology was first proposed in "Epistemology Naturalized", a seminal paper by W.V.O. Quine.[75] A less radical view has been defended by Hilary Kornblith in Knowledge and its Place in Nature, in which he seeks to turn epistemology towards empirical investigation without completely abandoning traditional epistemic concepts.[45]

Feminist epistemology

Feminist epistemology is a subfield of epistemology which applies feminist theory to epistemological questions. It began to emerge as a distinct subfield in the 20th century. Prominent feminist epistemologists include Miranda Fricker (who developed the concept of epistemic injustice), Donna Haraway (who first proposed the concept of situated knowledge), Sandra Harding, and Elizabeth Anderson.[77] Harding proposes that feminist epistemology can be broken into three distinct categories: Feminist empiricism, standpoint epistemology, and postmodern epistemology.

Feminist epistemology has also played a significant role in the development of many debates in social epistemology.[78]

Epistemic relativism

Epistemic relativism is the view that what is true, rational, or justified for one person need not be true, rational, or justified for another person. Epistemic relativists therefore assert that while there are relative facts about truth, rationality, justification, and so on, there is no perspective-independent fact of the matter.[79] Note that this is distinct from epistemic contextualism, which holds that the meaning of epistemic terms vary across contexts (e.g. "I know" might mean something different in everyday contexts and skeptical contexts). In contrast, epistemic relativism holds that the relevant facts vary, not just linguistic meaning. Relativism about truth may also be a form of ontological relativism, insofar as relativists about truth hold that facts about what exists vary based on perspective.[79]

Epistemic constructivism

Constructivism is a view in philosophy according to which all "knowledge is a compilation of human-made constructions",[80] "not the neutral discovery of an objective truth".[81] Whereas objectivism is concerned with the "object of our knowledge", constructivism emphasizes "how we construct knowledge".[82] Constructivism proposes new definitions for knowledge and truth, which emphasize intersubjectivity rather than objectivity, and viability rather than truth. The constructivist point of view is in many ways comparable to certain forms of pragmatism.[83]

Epistemic idealism

Idealism is a broad term referring to both an ontological view about the world being in some sense mind-dependent and a corresponding epistemological view that everything we know can be reduced to mental phenomena. First and foremost, "idealism" is a metaphysical doctrine. As an epistemological doctrine, idealism shares a great deal with both empiricism and rationalism. Some of the most famous empiricists have been classified as idealists (particularly Berkeley), and yet the subjectivism inherent to idealism also resembles that of Descartes in many respects. Many idealists believe that knowledge is primarily (at least in some areas) acquired by a priori processes, or that it is innate—for example, in the form of concepts not derived from experience.[84] The relevant theoretical concepts may purportedly be part of the structure of the human mind (as in Kant's theory of transcendental idealism), or they may be said to exist independently of the mind (as in Plato's theory of Forms).

Some of the most famous forms of idealism include transcendental idealism (developed by Immanuel Kant), subjective idealism (developed by George Berkeley), and absolute idealism (developed by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Friedrich Schelling).

Indian pramana

Indian schools of philosophy, such as the Hindu Nyaya and Carvaka schools, and the Jain and Buddhist philosophical schools, developed an epistemological tradition independently of the Western philosophical tradition called "pramana". Pramana can be translated as "instrument of knowledge" and refers to various means or sources of knowledge that Indian philosophers held to be reliable. Each school of Indian philosophy had their own theories about which pramanas were valid means to knowledge and which were unreliable (and why).[85] A Vedic text, Taittirīya Āraṇyaka (c. 9th–6th centuries BCE), lists "four means of attaining correct knowledge": smṛti ("tradition" or "scripture"), pratyakṣa ("perception"), aitihya ("communication by one who is expert", or "tradition"), and anumāna ("reasoning" or "inference").[86][87]

In the Indian traditions, the most widely discussed pramanas are: Pratyakṣa (perception), Anumāṇa (inference), Upamāṇa (comparison and analogy), Arthāpatti (postulation, derivation from circumstances), Anupalabdi (non-perception, negative/cognitive proof) and Śabda (word, testimony of past or present reliable experts). While the Nyaya school (beginning with the Nyāya Sūtras of Gotama, between 6th-century BCE and 2nd-century CE[88][89]) were a proponent of realism and supported four pramanas (perception, inference, comparison/analogy and testimony), the Buddhist epistemologists (Dignaga and Dharmakirti) generally accepted only perception and inference. The Carvaka school of materialists only accepted the pramana of perception, and hence were among the first empiricists in the Indian traditions.[90] Another school, the Ajñana, included notable proponents of philosophical skepticism.

The theory of knowledge of the Buddha in the early Buddhist texts has been interpreted as a form of pragmatism as well as a form of correspondence theory.[91] Likewise, the Buddhist philosopher Dharmakirti has been interpreted both as holding a form of pragmatism or correspondence theory for his view that what is true is what has effective power (arthakriya).[92][93] The Buddhist Madhyamika school's theory of emptiness (shunyata) meanwhile has been interpreted as a form of philosophical skepticism.[94]

The main contribution to epistemology by the Jains has been their theory of "many sided-ness" or "multi-perspectivism" (Anekantavada), which says that since the world is multifaceted, any single viewpoint is limited (naya – a partial standpoint).[95] This has been interpreted as a kind of pluralism or perspectivism.[96][97] According to Jain epistemology, none of the pramanas gives absolute or perfect knowledge since they are each limited points of view.

Domains of inquiry in epistemology

Social epistemology

Social epistemology deals with questions about knowledge in contexts where our knowledge attributions cannot be explained by simply examining individuals in isolation from one another, meaning that the scope of our knowledge attributions must be widened to include broader social contexts.[98] It also explores the ways in which interpersonal beliefs can be justified in social contexts.[98] The most common topics discussed in contemporary social epistemology are testimony, which deals with the conditions under which a belief "x is true" which resulted from being told "x is true" constitutes knowledge; peer disagreement, which deals with when and how I should revise my beliefs in light of other people holding beliefs that contradict mine; and group epistemology, which deals with what it means to attribute knowledge to groups rather than individuals, and when group knowledge attributions are appropriate.

Formal epistemology

Formal epistemology uses formal tools and methods from decision theory, logic, probability theory and computability theory to model and reason about issues of epistemological interest.[99] Work in this area spans several academic fields, including philosophy, computer science, economics, and statistics. The focus of formal epistemology has tended to differ somewhat from that of traditional epistemology, with topics like uncertainty, induction, and belief revision garnering more attention than the analysis of knowledge, skepticism, and issues with justification.

Metaepistemology

Metaepistemology is the metaphilosophical study of the methods, aims, and subject matter of epistemology.[100] In general, metaepistemology aims to better understand our first-order epistemological inquiry. Some goals of metaepistemology are identifying inaccurate assumptions made in epistemological debates and determining whether the questions asked in mainline epistemology are the right epistemological questions to be asking.

See also

References

Notes

- In Scots, the distinction is between wit and ken). In French, Portuguese, Spanish, Romanian, German and Dutch 'to know (a person)' is translated using connaître, conhecer, conocer, a cunoaște and kennen (both German and Dutch) respectively, whereas 'to know (how to do something)' is translated using savoir, saber (both Portuguese and Spanish), a şti, wissen, and weten. Modern Greek has the verbs γνωρίζω (gnorízo) and ξέρω (kséro). Italian has the verbs conoscere and sapere and the nouns for 'knowledge' are conoscenza and sapienza. German has the verbs wissen and kennen; the former implies knowing a fact, the latter knowing in the sense of being acquainted with and having a working knowledge of; there is also a noun derived from kennen, namely Erkennen, which has been said to imply knowledge in the form of recognition or acknowledgment.[19] The verb itself implies a process: you have to go from one state to another, from a state of "not-erkennen" to a state of true erkennen. This verb seems the most appropriate in terms of describing the "episteme" in one of the modern European languages, hence the German name "Erkenntnistheorie".

- See the main page on epistemic justification for other views on whether or not justification is a necessary condition for knowledge.

- Skeptical scenarios in a similar vein date back to Plato's Allegory of the Cave, although Plato's Allegory was quite different in both presentation and interpretation. In contemporary philosophical literature, something akin to evil demon skepticism is presented in brain in a vat scenarios. See also the New Evil Demon Problem (IEP).

- Compare to verificationism.

Citations

- "Epistemology". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- Steup, Matthias (2005). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Epistemology". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2014 ed.).

- "Epistemology". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- Borchert, Donald M., ed. (1967). "Epistemology". Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 3. Macmillan.

- Carl J. Wenning. "Scientific epistemology: How scientists know what they know" (PDF).

- "Epistemology". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- "The Epistemology of Ethics". 1 September 2011.

- "Epistemology". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. 2014.

- anonymous (November 1847). "Jean-Paul Frederich Richter". The Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature, Science and Art. 12: 317. hdl:2027/iau.31858055206621..

- Ferrier, James Frederick (1854). Institutes of metaphysic: the theory of knowing and being. Edinburgh: W. Blackwood. p. 46. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- Meyerson, Émile (1908). Identité et réalité. Paris: F. Alcan. p. i. Retrieved 21 June 2018.. See also Suchting, Wal. "Epistemology". Historical Materialism: 331–345.

- Locke, John (1689). "Introduction". An Essay Concerning Human Understanding.

- King James; Warren, Brett (2016). The Annotated Daemonologie. A Critical Edition. p. xiii. ISBN 978-1-5329-6891-4.

- Kant, Immanuel (1787). Critique of Pure Reason.

- Sturm, Thomas (2011). "Historical Epistemology or History of Epistemology? The Case of the Relation Between Perception and Judgment". Erkenntnis. 75 (3): 303–324. doi:10.1007/s10670-011-9338-3. S2CID 142375514.

- Stroud, Barry (2011). "The History of Epistemology". Erkenntnis. 75 (3): 495–503. doi:10.1007/s10670-011-9337-4. S2CID 143497596.

- John Bengson (Editor), Marc A. Moffett (Editor): Essays on Knowledge, Mind, and Action. New York: Oxford University Press. 2011

- For example, Talbert, Bonnie (2015). "Knowing Other People". Ratio. 28 (2): 190–206. doi:10.1111/rati.12059. and Benton, Matthew (2017). "Epistemology Personalized". The Philosophical Quarterly. 67 (269): 813–834. doi:10.1093/pq/pqx020.

- For related linguistic data, see Benton, Matthew (2017). "Epistemology Personalized". The Philosophical Quarterly. 67 (269): 813–834. doi:10.1093/pq/pqx020., esp. Section 1.

- "A Priori Justification and Knowledge". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "Belief". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "Formal Representations of Belief". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "Truth". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Gorgias. Project Gutenberg. 5 October 2008. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- Benardete, Seth (1984). The Being of the Beautiful. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. I.169. ISBN 978-0-226-67038-6.

- Benardete, Seth (1984). The Being of the Beautiful. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. I.175. ISBN 978-0-226-67038-6.

- Edmund L. Gettier, "Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?" Analysis, Vol. 23, pp. 121–123 (1963). doi:10.1093/analys/23.6.121

- "The Analysis of Knowledge". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Descartes, Rene (1985). The Philosophical Writings of Rene Descartes Vol. I. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-28807-1.

- Descartes, Rene (1985). Philosophical Writings of Rene Descartes Vol. II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-28808-8.

- Descartes, Rene (1985). The Philosophical Writings of Rene Descartes. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-28808-8.

- Gettier, Edmund (1963). "Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?" (PDF). Analysis. 23 (6): 121–123. doi:10.2307/3326922. JSTOR 3326922.

- Armstrong, D.M. (1973). Belief, Truth, and Knowledge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 152.

- Goldman, Alvin I. (1979). "Reliabilism: What Is Justified Belief?". In Pappas, G.S. (ed.). Justification and Knowledge. Dordrecht, Holland: Reidel. p. 11. ISBN 978-90-277-1024-6.

- Goldman, Alan H. (December 1976). "Appearing as Irreducible in Perception". Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 37 (2): 147–164. doi:10.2307/2107188. JSTOR 2107188.

- Richard L. Kirkham (1984). "Does the Gettier Problem Rest on a Mistake?" (PDF). Mind. 93 (372): 501–513. doi:10.1093/mind/XCIII.372.501. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2010.

- "Epistemic Contextualism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- "Certainty". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Bimal Krishna Matilal (1986). Perception: An essay on Classical Indian Theories of Knowledge. Oxford India 2002. ISBN 978-0-19-824625-1. The Gettier problem is dealt with in Chapter 4, Knowledge as a mental episode. The thread continues in the next chapter Knowing that one knows. It is also discussed in Matilal's Word and the World p. 71–72.

- Robert Nozick (1981). Philosophical Explanations. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-66448-7.Philosophical Explanations Chapter 3 "Knowledge and Skepticism" I. Knowledge Conditions for Knowledge pp. 172–178.

- D.M. Armstrong (1973). Belief, Truth and Knowledge. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-09737-6.

- Blackburn, Simon (1999). Think: A compelling introduction to philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-976984-1.

- Nagel, Jennifer (25 April 2013), "Knowledge as a Mental State", Oxford Studies in Epistemology Volume 4, Oxford University Press, pp. 272–308, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199672707.003.0010, ISBN 978-0-19-967270-7

- Brueckner, Anthony (2002). "Williamson on the primeness of knowing". Analysis. 62 (275): 197–202. doi:10.1111/1467-8284.00355. ISSN 1467-8284.

- Kornblith, Hilary (2002). Knowledge and its Place in Nature. Oxford University Press.

- Plato (2002). Five Dialogues. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Pub. Co. pp. 89–90, 97b–98a. ISBN 978-0-87220-633-5.

- Pritchard, Duncan; Turri, John. "The Value of Knowledge". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- Pritchard, Duncan (April 2007). "Recent Work on Epistemic Value". American Philosophical Quarterly. 44 (2): 85–110. JSTOR 20464361.

- Kvanvig, Jonathan L. (2003). The Value of Knowledge and the Pursuit of Understanding. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139442282.

- Zagzebski, Linda. "The Search for the Source of Epistemic Good" (PDF). Metaphilosophy. 34 (1/2): 13.

- Goldman, Alvin I. & Olsson, E.J. (2009). "Reliabilism and the Value of Knowledge". In Haddock, A.; Millar, A. & Pritchard, D. (eds.). Epistemic Value. Oxford University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-19-923118-8.

- Kvanvig, Jonathan (2003). The Value of Knowledge and the Pursuit of Understanding. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-521-03786-0.

- Kvanvig, Jonathan (2003). The Value of Knowledge and the Pursuit of Understanding. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-03786-0.

- BonJour, Laurence, 1985, The Structure of Empirical Knowledge, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wilson, E.O., Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 1975

- "The Analytic/Synthetic Distinction". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- Russell, G.: Truth in Virtue of Meaning: A Defence of the Analytic/Synthetic Distinction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2008

- John L. Pollock (1975). Knowledge and Justification. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey. ISBN 978-0-691-07203-6. p. 26.

- Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Foundational Theories of Epistemic Justification". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Warburton, Nigel (1996). Thinking from A to Z. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415433716.

- Klein, Peter D.; Turri, John. "Infinitism in Epistemology". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Haack, Susan (1993). Evidence and Inquiry: Towards Reconstruction in Epistemology. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-19679-2.

- "Skepticism". Encyclopedia of Empiricism. 1997.

- Klein, Peter (2015), "Skepticism", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2015 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 1 October 2018

- "Ancient Skepticism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Descartes' Epistemology". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "Descartes". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Peter Suber, "Classical Skepticism"

- Psillos, Stathis; Curd, Martin (2010). The Routledge companion to philosophy of science (1. publ. in paperback ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 129–138. ISBN 978-0-415-54613-3.

- Uebel, Thomas (2015). Empiricism at the Crossroads: The Vienna Circle's Protocol-Sentence Debate Revisited. Open Court. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8126-9929-6.

- Popkin, Richard (1972). "Skepticism". In Edwards, Paul (ed.). Encyclopedia of Philosophy Volume 7. Macmillan. pp. 449–461. ISBN 978-0-02-864651-0.

- "How to Make Our Ideas Clear".

- James, W. and Gunn, G. (2000). Pragmatism and other essays. New York: Penguin Books.

- Rorty, R. and Saatkamp, H. (n.d.). Rorty & Pragmatism. Nashville [u.a.]: Vanderbilt Univ. Press.

- Quine, Willard (2004). "Epistemology Naturalized". In E. Sosa & J. Kim (ed.). Epistemology: An Anthology. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 292–300. ISBN 978-0-631-19724-9.

- Kim, Jaegwon (1988). "What Is Naturalized Epistemology?". Philosophical Perspectives. 2: 381–405. doi:10.2307/2214082. JSTOR 2214082.

- "Feminist Epistemology". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- "Feminist Social Epistemology". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Boghossian, Paul (2006). Fear of Knowledge. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Raskin, J.D. (2002). Constructivism in psychology: Personal construct psychology, radical constructivism, and social constructivism. In J.D. Raskin & S.K. Bridges (Eds.), Studies in meaning: Exploring constructivist psychology (pp. 1–25). New York: Pace University Press. p. 4