Great Sioux Reservation

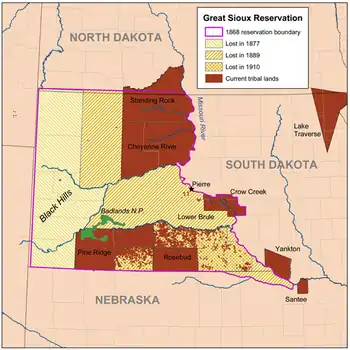

The Great Sioux Reservation was the original area encompassing what are today the various Sioux Indian reservations in South Dakota and Nebraska.

The reservation was established in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868,[1] and included all of present-day western South Dakota (commonly known as "West River" South Dakota) and modern Boyd County, Nebraska. This area was established by the United States as a reservation for the Teton Sioux, also known as the Lakota: the seven western bands of the "Seven Council Fires" (the Great Sioux Nation).

Reservation

In addition to the reservation dedicated to the Lakota, the Sioux reserved the right to hunt and travel in "unceded" territory in much of Wyoming and in the Sandhills and Panhandle of modern Nebraska. Because each band had its own territory, the US established several agencies through the Bureau of Indian Affairs to regulate the Lakota in this vast area.

The United States used the Missouri River to form the eastern boundary of the Reservation, but some of the land within this area had already assigned to other tribes, such as the Ponca. The Lakota Nation considered the West River area central to their territory, as it had been since their discovery of the Paha Sapa (Black Hills) in 1765, and their domination of the area after they conquered and pushed out the Cheyenne in 1776. Paha Sapa was sacred to the Lakota, and they considered it their place of origin, thousands of years earlier.

Custer's 1874 Black Hills Expedition from Fort Abraham Lincoln (near Bismarck, Dakota Territory) to the Black Hills or Paha Sapa discovered gold. The public announcement brought miners and open conflict with the Lakota. The US Army defeated the Lakota in the Black Hills War. By a new treaty of 1877, the US took a strip of land along the western border of Dakota Territory 50 miles (80 km) wide, plus all land west of the Cheyenne and Belle Fourche Rivers, including all of the Black Hills in modern South Dakota.

Most of the reservation remained intact for another 13 years.

General Allotment Act

In 1887, Congress passed the General Allotment Act, also called the Dawes Act to break up communal Indian lands into individual family holdings. On 2 March 1889, Congress passed another act (just months before North Dakota and South Dakota were admitted to the Union on 2 November 1889), which partitioned the Great Sioux Reservation, creating five smaller reservations:

- Standing Rock Reservation (which included land in modern North Dakota which had not been part of the Great Sioux Reservation), with its agency at Fort Yates;

- Cheyenne River Reservation, with its agency on the Missouri River near the Cheyenne River confluence (later moved to Eagle Butte following the construction of Oahe Reservoir);

- Lower Brule Indian Reservation, with its agency near Fort Thompson;

- Upper Brule or Rosebud Indian Reservation, with its agency near Mission, South Dakota; and

- Pine Ridge Reservation (Oglala Sioux), with its agency at Pine Ridge, South Dakota near the Nebraska border.

Neither the Crow Creek Reservation, east of the Missouri River in central South Dakota, nor the Fort Berthold Reservation, which straddles the Missouri River in western North Dakota, were part of the original Great Sioux Reservation.

After the boundaries of these five reservations was established, the government opened up approximately 9 million acres (36,000 km2), one-half of the former Great Sioux Reservation, for public purchase for ranching and homesteading. Much of the area was not homesteaded until the 1910s, after the Enlarged Homestead Act increased allocations to 320 acres (1.3 km2) for "semi-arid land".[2]

Settlement was encouraged by the railroads, and the US government issued publications of scientific instruction (since found to be incorrect) on how to farm the arid land. New European immigrants came to the area. The Lakota tribes received $1.25 per acre, usually used to offset agency expenses in meeting federal treaty obligations to the tribes.

Dawes Allotment Act

By the Dawes Allotment Act, the federal government intended to break up the communal tribal lands in Indian Territory and other reservations and allocate portions to households to encourage subsistence farming on the European-American model. Federal registrars recorded tribal members in each tribe, as land was allotted to heads of households. (The Dawes Rolls have been used by some tribes as the basis of historic documentation of membership.) The government allocated 160 acre (1.3 km2) parcels to heads of families, and declared any remaining land to be "surplus" and available for sale to non-natives. After a period of time, Native Americans could sell their land individually, and did.

The allotment of individual parcels and other measures reduced the total land in Indian ownership, while the government tried to force the people to convert to the lifestyles of subsistence farmers and craftsmen. The allocations were not based on accurate knowledge of whether the arid lands could support the small family farms envisioned by the government. This was largely an unsuccessful experiment for the Lakota and most homesteaders alike. Numerous European immigrants homesteaded the newly available lands on the Plains. Self-styled experts recommended regular tilling of the soil to "attract" moisture from the sky.[3]

The Plains were settled during what historians now know was a wetter than normal period and farmers had some early success. But, as more normal drought conditions returned, many farms folded. The farmers did not know how to best preserve the limited moisture in the soil, and farmers created the Dust Bowl conditions of the 1930s. Many had to abandon their land.[4] Today most farming is done by large-scale industrial farms which use different techniques, such as winter planting, to raise wheat.

By the 1960s, the five reservations had lost much of their territories, some through sales after the allotment process. In addition, the US seized land as part of federal water-control projects, such as construction of Lake Oahe and other mainstream reservoirs on the Missouri River as part of the Pick-Sloan Missouri Basin Program. The Rosebud Reservation, which once included all of four counties and part of another, has been reduced to a single county: Todd County in south-central South Dakota, although much Indian-owned land remained in the other counties. Similar reductions occurred in the other reservations.

Both inside and outside the reservation boundaries in West River, the Lakota are an integral part of the region and its history: many towns have Lakota names, such as Owanka, Wasta, and Oacoma. Towns such as Hot Springs, Timber Lake, and Spearfish are named in English after the original Lakota names. Some rivers and mountains retain Lakota names. The traditional Lakota game of buffalo and antelope graze together with cattle and sheep, and bison ranching is increasing on the Great Plains. Numerous monuments honor Lakota and European-American heroes and events.

Land claims

Although many non-Native homesteads were abandoned during the Dust Bowl-era of the 1930s, rather than reassigning the land to the Sioux, the federal government transferred much of the abandoned land to federal agencies; for instance, the National Park Service took over part of the modern National Grasslands and the Bureau of Land Management was assigned other land for management. In some cases, the US appropriated more land from the reduced reservations, as in the case of the WW2-era Badlands Bombing Range, taken from the Oglala Sioux of Pine Ridge. Although the range was declared surplus to USAF needs in the 1960s, it was transferred to the National Park Service rather than returned to the tribe's communal ownership.

Considering the Black Hills sacred and illegally taken, in the 20th century, the Lakota pursued a claim against the US government for the return of the land. In the 1980 United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians the United States Supreme Court ruled that the land had been taken illegally, and the US government offered financial compensation in settlement. The Oglala Lakota are persisting in their demand to have the land returned to their nation; the account with their compensation is earning interest.

References

- Kappler, Charles J.: Indian Affairs. Laws and Treaties. Washington 1904. Vol. 2, p. 998 ff.

- Raban, Bad Land, p. 23

- Raban, Bad Land, pp. 30-36

- Jonathan Raban, Bad Land: An American Romance, New York: Pantheon, 1996

- Nathan A. Barton, Environmental Assessment of Rosebud Indian Reservation (2003) [PLA Associates, Inc].

- Atlas of Western United States History (1989) [University of Oklahoma Press].

- Michael L. Lawson, "American Indian Heirship", South Dakota State Historical Society Quarterly (Spring 1991) vol 21, no. 1.

External links

- Map of the Great Sioux Reservation, adapted from Handbook of North American Indians: Plains, vol. 13, Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution

- "NEW LANDS FOR SETTLERS.; THE GREAT SIOUX RESERVATION IN SOUTHERN DAKOTA TO BE THROWN OPEN", New York Times, 10 February 1883, accessed Nov 2009

- "Act dissolving the Great Sioux Reservation", 2 Mar 1889, University of North Dakota