Grindlay family

The Grindlay family (Old English: Grynde Leá) is an ancient knightly family of England, whose presence in the country can be traced back to the 9th century.[1][2][3] Originating in Northumberland, the family now has two primary branches, one in the English Midlands and the other in the Scottish Lowlands, with a small presence in Ireland, America, New Zealand and South Africa.[2][3] The family established themselves as landed lords,[4][5][6][7] knights,[2][8][9] and gentry,[10][11][12] but more recently were prominent British bankers (see Grindlays Bank),[13] officials,[14][15] industrialists,[16][17] soldiers,[18][19][20] and freemasons during the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries.[21][22]

.svg.png.webp)

History

Anglo-Saxon Lineage

The family are reputed to be descended from the Anglo-Saxon knights, Harold and Athel Greenlee (c.850) of Green Chase, Northumberland.[2][23] The brothers were awarded the demesne of Balsal Chase or Bordeshale,[24][25][26] now Balsall Heath, in Warwickshire and its manors by King Alfred the Great for "heroic gallantry" during the Norfolk Campaign against the Danes.[2][3] Control of these lands and the surrounding region in Northern Warwickshire, the then Kingdom of Mercia, established the family in the Midland Counties in addition to the North of England and the Scottish Lowlands, the then Kingdom of Northumbria.[27]

"Of an ancient family "thorough Anglo Saxon" named Greenlee, called in the Midland Counties of England "The Greenlees"...two knights of this family...were gifted by King Alfred to a demesne in the County of Warwick...where this branch lived in opulence and high respect"[2] – Archives of Aston Hall, Warwickshire

13th, 14th and 15th Centuries

Originating from the combination of the Old English words grynde / gréne and leá / leâth meaning green valley or green clearing,[1][28][29][30][31] the English spelling of the family name developed several variants over time, principally Greneleye, Grenlay, and Gredley.[1][28][31][32] This is exemplified by the different ways the surname was recorded throughout this period, including Simon de Greneleye (c.1250),[33] William de Grenlay (c.1275),[28][34] and Hugh de Greneley (c.1290).[34]

By the High Medieval Period, the family were established landowners of the English Midlands, primarily in Warwickshire and Staffordshire, and later in Nottinghamshire.[35][36][37][38] They were involved in regional affairs of politics and administration as early as the 13th century onwards,[39] including Geoffrey de Greneleye or Grenleye,a and his son William de Greneley or Grenleye (c.1328), a man-at-arms or knight,[40] applying their warranty and seal to documents of the Chartulary of the Priory of St. Thomas near Stafford,[8][41] and Thomas de Grenlay (c.1349), incumbent rector of St John the Baptist Church, Clarborough.[42]

The Middle Ages saw several generations of the family take up arms against the French during the Hundred Years' War, most notably Sir William de Grenlay, William Greneleye or Guillaume Greenlee (c.1372).[2][43] William, and his soldiers, fought alongside Thomas Beauchamp, 12th Earl of Warwick, and Sir John Neville, heir apparent to the Earl of Westmorland,[43] but was slain at the Siege of Harfleur, and posthumously knighted by King Henry V.[2][7][8] His kinsmen, John Grenlay, Grenley or Greneley (c.1417) was also at the siege under the command of Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter, and subsequently garrisoned at Harfleur until it fell to the French in 1435,[8][44] and Thomas Grenlay or Greneley (c.1430) fought at the Siege of Louviers in 1431 and afterwards became twice Vice Chancellor of Oxford University in 1436 and 1437.[45][46]

During this same period, a cadet branch of the English arm of the family rose to prominence under William Gyrdeley, Gridley or Grindlay, who fought at the Battle of Agincourt as a member of the personal retinue of John Holland, 2nd Duke of Exeter, the then Earl of Huntingdon.[47][48][49] One of his kinsmen, Robin Grynelay or Gyrdeley, saw fighting at Le Neubourg under Henry Bourchier, 1st Earl of Essex until it was lost to the French in April 1444.[50][51] In 1425, William granted a portion of his lands in Ticehurst, Sussex to the Duke of Exeter, Sir Thomas Echyngham and others,[52][53] while he and his heirs subsequently established themselves at Rothley Court in Leicestershire and Boarzell Manor in Sussex.[54][55]

Throughout the late 13th, 14th and 15th centuries, the family were engaged in a number of notable land ownership disputes with neighbouring families, including those of de Denston,[56][57][58] Bagot, Barons of Bagot's Bromley,[59] Ferrers, Earls of Derby and Barons of Groby and Chartley,[60][61] Legh, Earls of Chichester and Barons of Stoneleigh and Newton,[62] and others,[63][64] regarding their lands in Nottinghamshire and Staffordshire. The family also frequently acted as arbiters for issues of succession for several others, including the Lyot, Purley and Wolaston (see William Wollaston) families of Staffordshire and Leicestershire.[8][65][66]

The close resemblance between the family name and those of several settlements in the surrounding area, such as Grindley in Staffordshire,[67][68] Grindley Brook in Shropshire,[69][70][71][72] Tushingham cum Grindley in Cheshire,[73][74][75] and Little Gringley, formerly spelt both Greneleye and Grenlay, in Nottinghamshire,[76][77][78] reflects the longstanding presence of the family in the region.

16th and 17th Centuries

Around the early 16th century, part of the family moved south west into the neighbouring county of Herefordshire, where they established landholdings near Kington.[27][79] In 1525, the estate of Woodhallhill Manor in Stanton on Arrow was granted to John Greneleye and his heirs, and the country house remained the seat of his successors thereafter.[6]

In the mid 16th century, the family were granted additional lands and estates in Ireland, near the city of Limerick, Munster,[2] by Queen Elizabeth I and Thomas Wentworth, 1st Baron Wentworth and Lord Chamberlain, to establish various armouries for small arms and culverin cannon.[3][12] As committed Presbyterians, the family line that settled in Ireland were subjected to religious persecution during the reign of King William III, and their lands and Hall were destroyed in response to the ongoing religious turmoil of the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly that surrounding the Battle of the Boyne.[2][27]

The family were invited into the protection of Trevor Hill, 1st Viscount Hillsborough and Wills Hill, 1st Marquess of Downshire and member of parliament for Warwick, but largely decided to leave Ireland and emigrate to America at the beginning of the 18th century.[2]

18th, 19th and 20th Centuries

The contemporary spellings of the family surname, themselves the result of further variation, are namely Greenly, of Titley Court,[2][6][8][28][32] Gridley, Barons of Stockport,[10][32][34] and Grindley or Grindlay, of Parkfields Manor and others.[9][28][80][81][82][83]

From the end of the 18th century onwards, the family actively participated in the closing stages of the Industrial Revolution, the expansion of the British Empire, and the global conflicts of WW1 and WW2, both civically and militarily.[18][84][85] Their involvement included distinguished military service,[86] the growth of the British financial system,[84] wartime government leadership,[85] and the development of pioneering industrial techniques.[87][88]

During the 19th and 20th centuries, a number of the family became prominent Freemasons, acting as members, officers, masters and founders of multiple Masonic lodges across the country, but particularly in Warwickshire and the wider English Midlands.[89][90][91]

Notable modern members of the English branch of the family include Captain Robert Melville Grindlay, the soldier, painter and founder of Grindlays Bank,[84][92][93][94][95] Lieutenant Colonel Henry Robert Grindlay, A.Q.M.G, of Her Majesty's 21st Hussars, decorated veteran of the First and Second Anglo-Sikh Wars,[18][86] Alfred Robert Grindlay, the founder of Grindlay Peerless and Lord Mayor of Coventry during World War II,[85][96][97] and William Harry Grindley, the 19th century ironstone industrialist and founder of the eponymous W H Grindley.[98][99][100]

Wider Family

Family Branches

The Scottish branch of the family is an ancestral sept of Clan Home and Clan Wedderburn, with the arms of Grindlay and Wedderburn sharing the motto 'Non Degener' (Not Degenerated).[101][102][103] The family principally resided near the ancient town of Grinnla, now Greenlaw,[104] in the Scottish Borders, where the spelling of the family name alternated between Greenlee,[1][105] Greenlaw,[106][107][108] Grenlay[109][110] and Grindlay.[111][112] The familial connection is illustrated by the congruent arms of Greenlee and Greenlaw,[80][113][114] the progenitors of Clan Home (see Sir Patrick de Greenlaw, descendant of Cospatric I, the Earl of Northumbria).[5][9][115]

More contemporary members of this line include George and William Grindlay, the 18th and 19th century leather magnates and landowners of the former Orchardfield Estate in Edinburgh,[11][116] Walter Grindlay, the Edinburgh and Liverpool based shipping grandee, shipmaster of the Grindlay during its saving of the India,[117][118][119] father of Lady Janet Grindlay Simpson, and cousin of Sir James Young Simpson, Bt (see Simpson Baronets of Strathavon and Edinburgh),[120][121][122] and the Right Honourable, Lord Grindley of Rannock.[4][11]

Another branch of the family exists in the United States (see James G Grindlay), who became highly decorated Unionist participants in the American Civil War following emigration from the United Kingdom during the 19th Century.[19]

Broader Relations

The Grindal family (see Edmund Grindal, Archbishop of Canterbury during the 16th century) are held to be close associates and possible relations.[1][32] The near synonymous family heraldry is believed to stem from this connection.[80][113][114]

Ancestral ties to both the noble Norman families of Grelley, formerly spelt Gredley, Greidley and Gredleye,[123][124][125] decedents of Albertus Greslet or 'Albert 'd'Avranches' de Greslé' (c.1050 - c.1100),[126][127][128] avowed Viscount of Avranches,[129] and the 1st Baron of Manchester (see House of Grailly), [130][131][132][133][134] and of Gresley, formerly spelt Greseleye,[34] Baronets of Drakelow Hall and decedents of Robert de Stafford (see House of Tosny),[135] have been presented by a number of 19th century historians, though are still the subject of research.[28][34][135][136][137][138]

Coats of Arms

Senior Branch

.jpg.webp)

Although the family had been using seals and insignia from the beginning of the 14th century,[41] the first known record of arms are from Sir William de Grenlay, William Greneleye or Guillaume Greenlee (c.1372) of Edgebaston, Warwickshire, who was commended for martial valour at the Siege of Harfleur, in Normandy, France, during the Hundred Years' War.[2][7][43] He was dubbed the "Knight of the Royal Guards" by King Henry V,[2][7] and as a reward, the family were entitled to have their armorial bearings topped with an additional crest (a green mound with sprig of oak) and motto (Fortes et fidelis).[2][113][114] The existing family escutcheon at that time was recorded as:

"Armorial Quartering...angular bars on the shield; the ermine, above Bar; and a square thereon"[2]

The "Armorial Quartering" refers to the division of the field into 4 square quarters, the "angular bars on the shield" to early pheons, and the "ermine, above Bar" to the tincture adjoining the central bar ordinaries, all of which are exhibited in the arms to this day.[139][140] This 14th century escutcheon is regarded as an early form of the arms now bourn by the Grindlay family,[101][102] with the current coat of arms adopted at some point during the 16th or 17th centuries, to differentiate their immediate familial line from their wider ancestral lineage.[6][80][113][114]

The arms of the related but distinct branches of the Grindlay family, are identifiable by their differing heraldic crests, which among them include a buffalo, a peahen and a dove.[113][114][140][141]

Examples of the recorded arms of Grindlay and Grindley, illustrating their relatively fluid interchangeability up until the 19th century, are as follows:

- "Crest – a dove, proper." Deuchar, 1817

- "Crest – a buffalo's head erased, gules." Deuchar, 1817

- "Per cross, or and az. a cross quarterly, erm. and of the first, betw. four pheons countercharged, of the field. Crest, a pea-hen ppr. Motto, non degener." Robson, 1830

- "Az. a cross betw. four pheons or. Crest, a buffalo's head erased gu." Robson, 1830

- "Crest – A buffalo's head erased. gu., a dove ppr., a pea-hen ppr. Motto – Non degener" Fairbairn, 1860, 1905, 1911

- "A dove ppr., pea-hen, ppr, and a buffalo's head erased" Washbourne, 1882

- "A dove, ppr.; and another, a pea-hen, ppr." Elven, 1882

- "A buffalo's head erased, gu." Elven, 1882

- "A buffalo's head, erased, gu., a dove, ppr., a pea-hen, ppr." MacVeigh, 1883

- "Quarterly, or and az. a cross quarterly erm. and of the first, betw. four pheons counterchanged of the field. Crest – A pea-hen ppr. Motto – Non Degener" Burke, 1884

- "Az. a cross betw. four pheons or. Crest – a buffalo's head erased gu." Burke, 1884

Cadet Branches

The Warwickshire line of the family gave rise to two separate cadet branches, one in Nottinghamshire and then a second in Leicestershire and Sussex. Both cadet branches attained arms in their own right.

Nottinghamshire

The Nottinghamshire cadet branch adopted arms as early as the 14th century, attributed to William, son of John de Grenleye (c.1374) of the County of Nottingham.[37] First documented in the Catalogue of Seals of the Department of Manuscripts of the British Museum,[142] the arms are described as:

"A bend bretessed, between three crescents"

Identified by Walter de Grey Birch in 1894, the arms were recovered from a gothic panel and described as dark red but indistinct in colour,[142] indicative of a gules escutcheon and likely faded argent charges,b due to the tendency for silver paint to oxidise and darken over time (see Tincture: Argent).[143]

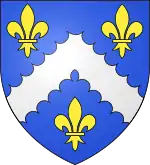

Leicestershire and Sussex

The arms of the Leicestershire and Sussex cadet branch of the family were first recorded in Wriothesley's Chevrons (c.1525) by Sir Thomas Wriothesley, 1st Earl of Southampton (1505 – 1550).[49] The armorial bearings are described in this and later works, including the Dictionary of British Arms – Medieval Ordinary,[9] as:

"Azure a chevron engrailed argent between 3 fleurs de lis or"

The arms of the cadet branch illustrate a number of parallels with those of Clan Kinninmont of Kinninmoth near Fife in Scotland, an area where the Grindlay family are known to have settled.[9][49][108][144][120] The close resemblance extends to the clan crest and badge which feature an oak tree or sprig of oak.[110][145]

Houses and Estates

Notable family residences:

- Bordeshale Manor, Warwickshire (historic family seat - destroyed)

- Parkfields Manor, Staffordshire

- Rothley Court, Leicestershire

- Westcote Manor, Warwickshire

- Woodhillhall Manor, Herefordshire

- Carshalton Park House, Surrey

- Boarzell Manor, Sussex

- Rannoch Barracks, Perthshire

- Orchardfield Estate, Edinburgh

- Derwent Island House, Cumbria

Other prominent residences of the wider family:

- Titley Court, Herefordshire (primary residence of Greenly line)

- Strathavon Lodge, Edinburgh (primary residence of Grindlay Simpson line)

- Culwood House, Buckinghamshire (primary residence of Gridley line)

Gallery

.jpg.webp) Undifferenced full heraldic achievement of the senior English branch of the Grindlay family. (black & white image) (20th century)

Undifferenced full heraldic achievement of the senior English branch of the Grindlay family. (black & white image) (20th century) Arms of the Grindlay family of Warwickshire (19th century)

Arms of the Grindlay family of Warwickshire (19th century) The extent of the Orchardfield Estate of the Grindlay family in central Edinburgh, Scotland. (Illustrated on the 1817 map of 'The City of Edinburgh and its environs.' created by Robert Kirkwood)

The extent of the Orchardfield Estate of the Grindlay family in central Edinburgh, Scotland. (Illustrated on the 1817 map of 'The City of Edinburgh and its environs.' created by Robert Kirkwood) Rothley Court, one of the residences of the family during the 15th century and later home to the Babington family.

Rothley Court, one of the residences of the family during the 15th century and later home to the Babington family. Derwent Island House, country residence and eventual place of death of Reginald Robert Grindlay, son of Alfred Robert Grindlay.[146]

Derwent Island House, country residence and eventual place of death of Reginald Robert Grindlay, son of Alfred Robert Grindlay.[146] Rannock Barracks, the residence of Lord Grindley during the 19th century and now home to Baron Pearson of Rannoch.

Rannock Barracks, the residence of Lord Grindley during the 19th century and now home to Baron Pearson of Rannoch. Escutcheon of the achievement of arms of Grindlay, senior branch. (18th century)

Escutcheon of the achievement of arms of Grindlay, senior branch. (18th century).gif) Escutcheon of the achievement of arms of Grindlay, cadet branch. (18th century)

Escutcheon of the achievement of arms of Grindlay, cadet branch. (18th century)

See also

- Grindlay

- Grindlays Bank

- Grindlay Peerless

- W H Grindley

- Clan Home

- Clan Wedderburn

- Clan Kinninmont

- Earls of Northumbria

- Barons Gridley

- Gresley Baronets

- Simpson Baronets

- House of Grailly

- House of Tosny

- Robert Melville Grindlay, Founder of Grindlay's Bank

- Alfred Robert Grindlay, Lord Mayor of Coventry and Founder of Grindlay Peerless

- William Harry Grindley, Founder of W H Grindley

- James Glas Grindlay, Union Army Officer during the American Civil War

- Edmund Grindal, Archbishop of Canterbury

- Albertus Greslet, 1st Baron of Manchester

- Richard le Goz, 2nd Vicomte d'Avranches, professed father of Albertus Greslet

- List of family seats of English nobility

Footnotes

References

- Harrison, Henry (1969). Surnames of the United Kingdom: A Concise Etymological Dictionary. London: Clearfield. p. 176. ISBN 9780806301716.

- Greenlee, Ralph Stebbins (1908). Genealogy of the Greenlee Families in America, Scotland, Ireland and England. Privately Printed.

- Burchinal, Beryl Modest (1990). The Ganss-Gans Genealogy, 1518-1990: Ancestors in Germany and Descendants in Pennsylvania of George Baltzer Gans, 1684-1760, Germany-Pennsylvania, the Immigrant Ancestor. Suburban Print. & Publishing Company and Penn State Book Binding Company.

- Pigot, J (1837). Pigot & Co's National Commercial Directory of the whole of Scotland and of the Isle of Man: with a General Alphabetical List of the Nobility, Gentry and Clergy of Scotland. Pigot & Co. pp. 678, 806.

The Right Hon. Lord Grindley of Rannock

- Nisbet, Alexander (1816). A System of Heraldry. William Blackwood. p. 270.

- Burke, John (1837). A Genealogical and Heraldic History of The Landed Gentry or Commoners of Great Britain and Ireland, enjoying territorial possessions or high official rank, but uninvested with heritable honours. Henry Colburn. p. 292.

- Fiennes, Sir Ranulph (2014). Agincourt: My Family, the Battle and the Fight for France. Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 9781444792102.

- "The 1000 Year History of The 'de Greneleye' Family".

- Wagner, Sir Anthony (1996). Dictionary of British Arms - Medieval Ordinary Vol.II. London: The Society of Antiquaries of London.

- The English Ancestry of Thomas Gridley of Windsor and Hartford, Connecticut (1612 - 1655). Thomas Boslooper, PhD.

- Rodger, Richard (2001). The Transformation of Edinburgh: Land, Property and Trust in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521602822.

- McAnlis, Virginia Wade (1994). The Consolidated Index to the Records of the Genealogical Office Dublin, Ireland. National Library of Ireland.

- "RBS Heritage Hub".

- McGrory, David. Coventry's Blitz. Amberley Publishing Limited.

- "Coventry City Council Public Report". Coventry City Council. 14 July 2015. Archived from the original on 4 October 2015.

- Kimberley, Damien (2012). Coventry's Motorcar Heritage. History Press Limited.

- "www.historiccoventry.co.uk".

- Hart, Colonel H. G. (1866). The New Annual Army List and Militia List for 1866 (PDF). London: John Murray. pp. 76, 81c.

- Brainard, Mary Genevie Green (1915). Campaigns of the One Hundred and Forty-sixth Regiment, New York State Volunteers. New York and London: G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- Campbell Esq., Lawrence Dundas (1804). Asiatic Annual Register. London. p. 166.

- "History of Stivichall Lodge".

- "Reports of Masonic Meetings" (PDF). The Freemason. 13 (600): 395. 1880.

- Mawer, Allen (1920). The Place-Names of Northumberland and Durham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 96.

Greencroft (Greenlee or Greenleye)

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Edward I: Volume 4, 1301-1307. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London (BHO: British History Online). 1898.

- Calendar of Fine Rolls, Edward II: Volume 3, 1319 - 1327 (PDF). Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London. 1912.

- Dargue, William. "A History of Birmingham Places & Placenames from A to Y".

- Greenlee, Robert Lemuel (1908). Genealogy of the Greenlee families: with ancestors of Elizabeth Brooks Greenlee and Emily Brooks Greenlee, also genealogical data on the McDowells of Virginia and Kentucky.

- Reaney, Percy (1958). A Dictionary of English Surnames. Routledge. ISBN 9780415057370.

- "Grindlay Single Name Study Project".

- "www.forebears.io".

- Horovitz, David (2003). "A Survey and Analysis of the Place-Names of Staffordshire". PHD Thesis. 2 – via Nottingham University.

- Hanks, Patrick (2003). Dictionary of American Family Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199771691.

- Cooper, C.P. (1836). Excerpts from the Roll of Fines in the Tower of London from the reign of Henry III (1216 - 1272). United Kingdom: The Commissioners of Public Records (House of Commons) by order of King William VI. p. 331.

Simone de Greneleye

- Hanks, Patrick (2016). The Oxford Dictionary of Family Names in Britain and Ireland. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192527479.

- Fine Roll C 60/57, 44 HENRY III (1259–1260). Henry III Fine Rolls Project. Lay summary.

- Chadwick, Howard (1924). "History of Dunham-on-Trent, with Ragnall, Darlton, Wimpton, Kingshaugh, etc: Wimpton". www.nottshistory.org.uk.

Witnesses to grants of lands in Nottinghamshire. Hugh de Grenlay and William(s) de Grenley. (28 May 1307).

- Birch, W. de G. (1894). Catalogue of seals in the Department of manuscripts in the British Museum. London: William Clowes and Sons.

William, son of John de Grenleye, of co. Notts. [A.D. 1374]. Dark-red: indistinct. A shield of arms: a bend bretessed, betw. three crescents. Within a gothic panel.

- Inquisitions Post Mortem, Edward I, File 19. His Majesty's Stationery Office, London (BHO: British History Online). 1906. pp. 149–156.

Multiple references to family (Grenlay) lands in Nottinghamshire.

- Roberts, Caroli (1836). Excerpta È Rotulis Finium in Turri Londinensi Asseratis Henrico Tertio Rege, A.D. 1216 - 1272 Volume 2. The Royal Library at The Hague. p. 331.

Simonis de Greneleye

- Salt, T (1887). Collections for a history of Staffordshire. Harrison and Sons.

Willielmus (William) Grenleye one of a small group of 'militibus' to witness the signing of local legal documents (plea rolls).

- Salt, T (1887). Collections for a history of Staffordshire. Harrison and Sons.

Multiple accounts of the activities of Galfridi (Geoffrey), Willielmus (William) and John de Grenleye.

- "Southwell and Nottingham Church History Project". www.southwellchurches.nottingham.ac.uk.

1349. Thomas, son of Robert de Grenlay

- "The Medieval Soldier Project". University of Southampton and University of Reading.

1. William Greneleye (Captain: Thomas Beauchamp, 1339-1401, Earl of Warwick); 2. William de Grenlay (Captain: John Neville)

- "The Medieval Soldier Project". University of Southampton and University of Reading.

1. John Grenlay (Captain: Thomas Beaufort, 1377-1426, Earl of Dorset, Duke of Exeter); 2. John Greneley / John Grenley (Captain: William Minors)

- "The Medieval Soldier Project". University of Southampton and University of Reading.

Thomas Grenlay, Man-at-Arms (Captain: Sir William Fulthorp)

- "University of Oxford website - (Home/About/OrganisationUniversity Officers/Vice-Chancellor/Previous Vice-Chancellors)".

- Harris Nicholas Esq., Nicholas (1827). The History of the Battle of Agincourt: And of the Expedition of Henry the Fifth in France: To which us added, The Roll of the Men at Arms in the English Army. London: Johnson: Harvard College Library. p. 498.

- "The Medieval Soldier Project". University of Southampton and University of Reading.

William Gyrdeley, Man-at-Arms (Captain: John Holland,1395-1447, Earl of Huntingdon, Duke of Exeter; Commander: Henry V, 1386-1442, King of England)

- Wriothesley, Sir Thomas. A collection of arms, some coloured, pedigrees and other heraldic material. Early 16th century, with later 16th century additions.

- "The Medieval Solider Project". University of Southampton and University of Reading.

Robin Grynelay, Archer (Captain: Henry Bourchier [1408 - 1483] Count of Eu, Earl of Essex)

- Jones, Michael K (1982). The Beaufort family and the war in France 1421-1450. Bristol: University of Bristol. p. 319.

- Girders, Ian. "Girders Medieval Biological Index".

- "East Sussex Records Office". The National Archives.

- "Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland Records Office". The National Archives.

Documents relating to the Manor and Soke of Rothley

- "East Sussex Records Office". The National Archives.

Deeds of the Manor of Boarzell and land in Ticehurst and Etchingham

- Wrottesley, George (1890). Collections for a History of Staffordshire. Harrison and Sons.

Nicholas de Denston, complainant, and William de Greneleye. 20th January, 1328.

- McSweeney, Thomas. J. (2014). The Kings Courts and the Kings Soul: Pardoning as Almsgiving in Medieval England (PDF).

Land granted to Nicholas de Denton later subjected to dispute.

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Henry III: Volume 5, 1258-1266. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 1910. p. 464.

Grant for life to Nicholas de Denton for an oratory.

- Staffordshire Historical Collections, Vol. 11. Staffordshire Fines: 1-10 Edward III. London: Staffordshire Record Society. 1890. pp. 127–141.

Nicholas de Denston (affiliate of the Barons of Bagot's Bromely) vs William de Greneleye concerning land acres of land Bromleye Bagot.

- "Plea Rolls for Staffordshire: 7 Edward I (1239 – 1307)". The National Archives. Staffordshire Record Society. 1885 [1885]. pp. 92–102.

Alianora [Eleanor] the widow of Robert de Ferrars [Ferrers] vs Henry de Grenley, Geoffrey de Warilowe (de Grenleye) and others.

- Collections for a history of Staffordshire - Plea Rolls of the reign of Edward I.Staffordshire Record Society. Birmingham, England: Houghton and Hammond. 1885. pp. 96–97.

Alianora [Eleanor] the widow of Robert de Ferrars [Ferrers] vs Henry de Grenley, Geoffrey de Warilowe (de Grenleye) and others.

- "Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent Archive Service: Staffordshire County Record Office". The National Archives.

Matilda, widow of Robert son of Thomas de Grenleye vs Thomas del Leghe of Neuton. Witnesses including Ralph Bagot and Thomas Bagot.

- "Staffordshire Deeds: Grindley". The National Archives. Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent Archive Service: Staffordshire County Record Office.

William son of Geoffrey de Warilowe de Grenleye vs Prior and Convent of St. Thomas the Martyr by Stafford

- Palmer, Robert. "Feet of Fines: CP 25/1/184/26". http://www.medievalgenealogy.org.uk. Lay summary.

Thomas de Wouer vs Adam, son of William de Grenleye, regarding 1 messuage, 2 mills, 5 and a half bovates of land and 45 acres of meadow and 54 shillings of rent. 13th November, 1329.

External link in|website=(help) - Collections for a History of Staffordshire. London: Harrison & Sons. 1887.

- "Northamptonshire Archives". The National Archives. 14 July 1468.

- Bowcock, E. W. (1923). Shropshire Place Names. Wilding & Son, Limited, Printers.

- Mutschmann, Heinrich (1913). The Place-Names of Nottinghamshire: Their Origin and Development. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107665415.

- Johnston, James Brown (1915). The Place-Names of England and Wales. J. Murray (University of Michigan).

- Gelling, Margaret (2004). Survey of English Place Names of Shropshire. English Place-Name Society. ISBN 9780904889765.

- "The Survey of English Place-Names: British Academy Research Project". The English Place-Name Society. 1923.

Grindley, Grindley Brook, Grindley Brook Bridge

- "Survey of English Place-Names: British Academy Research Project". The English Place-Name Society. 1923.

Grindleybrook

- Dodgson, J. McN. (1972), The place-names of Cheshire. Part four: The place-names of Broxton Hundred and Wirral Hundred, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 47, ISBN 0-521-08247-1

- Dodgson, J. McN. (1981). The place-names of Cheshire: The place-names of the city of Chester ; the elements of Cheshire place-names (A-Gylden). English Place-Name Society. ISBN 9780904889079.

- "The Survey of English Place-Names: British Academy Research Project". The English Place-Name Society. 1923.

Tushingham cum Grindley

- Mutschmann, Heinrich (1913). The Place-Names of Nottinghamshire: Their Origin and Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 59–60.

Gringley

- "The Survey of English Place-Names: British Academy Research Project". The English Place-Name Society. 1923.

Little Gringley

- "Survey of English Place-Names: British Academy Research Project". The English Place-Name Society. 1923.

Gringley on the Hill

- "Will of Philippe Greneley of Moldeley in Lughurnes, Herefordshire". The National Archives, Kew. 10 May 1504.

- Burke, Sir Bernard (1884). The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales: Comprising a Registry of Amorial Bearings from the Earliest to the Present Time. London: Harrison & Sons.

- Calendar of Close Rolls, Edward III: Volume 4, 1337-1339. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London. 1990.

- Lower, Mark Antony (1860). Patronymica Britannica: A Dictionary of the Family Names of the United Kingdom. John Russel Smith.

- Deacon, Charles William (1902). The Court Guide and County Blue Book of Warwickshire, Worcestershire, and Staffordshire. London: Charles William Deacon & Co. pp. 382 (section: Landed Gentry, Country Families, etc.).

William Harry Grindley Esq, JP - Tunstall and Parkfields, Tittensor, Stoke on Trent

- Geoffrey Tyson, 100 Years of Banking in Asia and Africa, (1963)

- McGrory, David. Coventry's Blitz. Amberley Publishing Limited.

- Hart, Colonel H. G. (1871). The New Annual Army List and Militia List and Indian Civil Service List for 1871 (PDF). London: John Murray. pp. 60–61, 620.

- Jackson, Colin (2013). Classic British Motorcycles. Fonthill Media.

- "Obituary - Dr Robert Walter Guy Grindlay". The British Medical Journal: 1658. 1963.

Dr R. W. G. Grindlay, M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P., D.A., F.F.A., R.C.S. was a post-war medical pioneer who's advances in anesthetics were to prove "epoch-making". He was husband to Pamela Francis Campbell-Brabazon, daughter of General John St. Clair Campbell-Brabazon (see Campbell baronets, of St Cross Mede).

- "www.stivichall-lodge.org.uk".

- "The British News Paper Archive". Coventry Evening Telegraph. 21 April 1965.

- United Grand Lodge of England Freemason Membership Registers, 1751-1921. London, England: Library and Museum of Freemasonry; London, England.

20th May 1836 - Grindlay, Robert Melville. East India Agent

- "Capt. Robert Melville Grindlay (The Print Gallery)". The Map House (www.themaphouse.com).

- Chatterjee, Arup K Chatterjee. "Robert Melville Grindlay: The artist, Indophile and imperialist who founded Grindlays Bank". Scroll In.

- Grindlay, Robert Melville (1830). Scenery, Costumes and Architecture, Chiefly on the Western Side of India. Smith, Elder & Company.

- "London Metropolitan Archives: City of London". The National Archives.

Robert Melville Grindlay esq, and others of Leamington Priors, Warwickshire, appointed as trustees for Harriet Rokeby of Oxenden near Market Harborough, Northamptonshire

- "www.historiccoventry.co.uk".

- Kimberley, Damien (2012). Coventry's Motorcar Heritage. History Press Limited.

- "W H Grindley and Company Limited". Collections Online. Science Museum Group. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- "Major accessions to repositories in 2008 relating to Business". National Archives. 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- "WH Grindley & Co Ltd, earthenware manufacturers, Tunstall GB/NNAF/C95818". National Register of Archives. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- Elven, John Peter (1882). The book of family crests : comprising nearly every family bearing, properly blazoned and explained ... with the surnames of the bearers, alphabetically arranged, a dictionary of mottos, an essay on the origin of arms, crests, etc., and a glossary of terms. Harold B. Lee Library. London : Reeves and Turner.

- Washbourne, Henry (1861). The Book of mottos, borne by nobility and gentry, public companies, cities, etc. Fraser and Crawford.

- "www.scotclans.com".

- "Blaeu Atlas of Scotland - Map Placenames search - National Library of Scotland". maps.nls.uk. Retrieved 2018-09-25.

- "Sheriff Court Filiation and Aliment Decrees of Scotland". www.oldscottish.com.

Elizabeth Greenlee or Grindlay. Scotland

- Index to Register of Deeds Preserve in HM General Registry House. Her Majesty's Stationery Office - Scottish Record Office. 1682.

Grindlay (Greenlaw or Grinlay)

- "Scotland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1564-1950". www.ancestry.com.

Ralf Greenlaw or Grindlay

- "Geneanet". www.geneanet.org. Lay summary.

Alison Greenlaw or Grindlay (b.1798) of Fife, Scotland. Daughter of John Greenlaw or Grindly.

- Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 21 Part 2, September 1546-January 1547. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. 1910. pp. 609–627.

Greenlaw (Grenlaw, Girnelay, Grenlay, Greynley), in Scotland

- Black, George Fraser (1946). The Surnames of Scotland: Their Origin, Meaning, and History. New York Public Library. ISBN 9780871041722.

- Dobson, David (2003). The Scottish Surnames of Colonial America. Clearfield Company. ISBN 9780806352091.

- Calendar of State Papers Domestic: James I, 1611-18. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1858.

- John Burke Esq. &, Sir John Bernard Burke (1844). Encyclopædia of Heraldry, Or General Armory of England, Scotland and Ireland: Comprising a Registry of All Armorial Bearings from the Earliest to the Present Time, Including the Late Grants by the College of Arms. H. G. Bohn.

- Robson, Thomas (1830). The British Herald or Cabinet of Armorial Bearings of the Nobility and Gentry of Great Britain and Ireland. Turner & Marwood.

- Whyte, Donald (2000). Scottish Surnames. Birlinn. ISBN 9781841580562.

- "Orchardfield Estate. The property of George Grindlay's Trust". National Library of Scotland (Estate Maps of Scotland, 1730s - 1950s).

The portion of the Grindlay family's Orchardfield Estate put into the George Grindlay Trust following his death.

- "They came by the 'Grindlay' as Self-funded and as Bounty Immigrants in 1841". In Victoria before 1848.

- "Passengers in History: An initiative of the South Australian Maritime Museum". Passengers in History.

- Tao, Kim (2017). "Meeting the descendants from a disaster at sea". Australian National Maritime Museum.

- McCrae, Morrice (2010). Simpson: The Turbulent Life of a Medical Pioneer. John Donald, Edinburgh.

1. Walter Grindlay being cousin of James Young Simpson (Grandmother of Isabella Grindlay). 2. Lady Janet Grindlay staying with family in Fife. 3. The extended Grindlay Simpson family. 4. The Grangemouth and Liverpool based operations of Walter Grindlay.

- "The History of Anaesthesia Society Proceedings: Volume 44" (PDF). 2011. p. 144.

- Foster, Joseph (1881). The baronetage and knightage. p. 566.

The arms of Walter Grindlay Simpson (Grindlay Simpson family)

- Farrer, William (1901). The Barony of Grelley: The Historical Society of Lancashire and Cheshire (PDF). Liverpool Public Library.

- Remains Historical & Literary connected with the Palatine Counties of Lancaster and Chester (PDF). Manchester: The Chetham Society. 1872. p. 131.

- Collections for a history of Staffordshire: Staffordshire Record Society. Birmingham, England: Houghton and Hammond. 1894. p. 85.

- Browne, William (1958). A Dictionary of English Surnames. Routledge.

- "Page:The Ancestor Number 1.djvu/259". Wikisource.

- Blakeley, Allen. "A Short History of Blackley". Blakeley ONS Gazette in 2002.

- André, Davy (2009). Les barons du Cotentin. Eurocibles.

- Hibbert, Samuel (1848). History of the foundations in Manchester of Chirst's College.

- Reilly, John (1859). The people's history of Manchester. John Heywood.

- "www.aboutmanchester.com".

- "www.manchestercathedral.org". Archived from the original on 2016-04-16. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- Butterworth, James. The annals of Manchester: a chronological record from the earliest times to the end of 1885: Manchester Historical Recorder. J. Bradshaw.

- Madan, Falconer (1899). The Gresleys of Drakelowe: An Account of the Family, and Notes of Its Connexions by Marriage and Descent from the Norman Conquest to the Present Day with Appendixes, Pedigrees and Illustrations. Oxford University Press.

- Seary, E. R. (1977). Family Names of the Island of Newfoundland. McGill Queen University Press. ISBN 9780773567412.

- Tait, James (1904). Mediaeval Manchester and the Beginnings of Lancashire. pp. 120–123.

- Whatton, William Robert (1824). Observations on the Armorial Bearings of the town of Manchester and on the Decent of the Baronial Family of Grelley. Manchester: Robinson and Bent.

- Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles (1909). A Complete Guide to Heraldry. TC & EC Jack.

- MacVeigh, James (1883). Royal Book of Crests of Great Britain, Ireland and dominion of Canada, India and Australia. Legislative Library of Ontario.

- Fairbain, James (1911). Fairbain's Crests of the leading families in Great Britain and Ireland and their kindred in other lands. Heraldic Publishing Company. ISBN 9780343430832.

- de Grey Birch, Walter (1894). Catalogue of Seals in the Department of Manuscripts in the British Museum: Volume 3. London: The British Museum. p. 34.

- Charles Fox-Davies, Arthur (1909). A Complete Guide to Heraldry. London: T. C. & E. C. Jack. p. 70. Lay summary.

With regard to the other metal, silver, or, as it is always termed, "argent," the same variation is found in the usage of silver and white in representing argent that we find in yellow and gold, though we find that the use of the actual metal (silver) in emblazonment does not occur to anything like the same extent as does the use of gold. Probably this is due to the practical difficulty that no one has yet discovered a silver medium which does not lose its colour. The use of aluminium was thought to have solved the difficulty, but even this loses its brilliancy, and probably its usage will never be universally adopted.

- "Fife Place-Name Data - Kinninmonth". Glasgow University Website.

- "Kinninmont". MyClan (www.myclan.com). Archived from the original on 22 May 2006. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- "The British News Paper Archive". Coventry Evening Telegraph. 21 April 1965.