Religious persecution

Religious persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or a group of individuals as a response to their religious beliefs or affiliations or their lack thereof. The tendency of societies or groups within societies to alienate or repress different subcultures is a recurrent theme in human history. Moreover, because a person's religion often determines his or her morality, world view, self-image, attitudes towards others, and overall personal identity to a significant extent, religious differences can be significant cultural, personal, and social factors.

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

Religious persecution may be triggered by religious bigotry (i.e. when members of a dominant group denigrate religions other than their own) or it may be triggered by the state when it views a particular religious group as a threat to its interests or security. At a societal level, the dehumanisation of a particular religious group may readily lead to violence or other forms of persecution. Indeed, in many countries, religious persecution has resulted in so much violence that it is considered a human rights problem.

Definition

David T. Smith, in Religious Persecution and Political Order in the United States, defines religious persecution as "violence or discrimination against members of a religious minority because of their religious affiliation," referring to "actions that are intended to deprive individuals of their political rights and to force minorities to assimilate, leave, or live as second-class citizens.[1] In the aspect of a state's policy, it may be defined as violations of freedom of thought, conscience and belief which are spread in accordance with a systematic and active state policy which encourages actions such as harassment, intimidation and the imposition of punishments in order to infringe or threaten the targeted minority's right to life, integrity or liberty.[2] The distinction between religious persecution and religious intolerance lies in the fact that in most cases, the latter is motivated by the sentiment of the population, which may be tolerated or encouraged by the state.[2] The denial of people's civil rights on the basis of their religion is most often described as religious discrimination, rather than religious persecution.

Examples of persecution include the confiscation or destruction of property, incitement of hatred, arrests, imprisonment, beatings, torture, murder, and executions. Religious persecution can be considered the opposite of freedom of religion.

Bateman has differentiated different degrees of persecution. "It must be personally costly... It must be unjust and undeserved... it must be a direct result of one's faith."[3]

Sociological view

From a sociological perspective, the identity formation of strong social groups such as those generated by nationalism, ethnicity, or religion, is a causal aspect of practices of persecution. Hans G. Kippenberg says it is these communities, who can be a majority or a minority, that generate violence.[4]:8,19,24 Since the development of identity involves 'what we are not' as much as 'what we are', there are grounds for the fear that tolerance of 'what we are not' can contribute to the erosion of identity.[5] Brian J. Grim and Roger Finke say it is this perception of plurality as dangerous that leads to persecution.[6]:2 Both the state, and any dominant religion, share the concern that to "leave religion unchecked and without adequate controls will result in the uprising of religions that are dangerous to both state and citizenry," and this concern gives both the dominant religion and the state motives for restricting religious activity.[6]:2,6 Grim and Finke say it is specifically this religious regulation that leads to religious persecution.[7] R.I. Moore says that persecution during the Middle Ages "provides a striking illustration of the classic deviance theory, [which is based on identity formation], as it was propounded by the father of sociology, Emile Durkheim".[8]:100 Persecution is also, often, part of a larger conflict involving emerging states as well as established states in the process of redefining their national identity.[6]:xii,xiii

James L.Gibson[9] adds that the greater the attitudes of loyalty and solidarity to the group identity, and the more the benefits to belonging there are perceived to be, the more likely a social identity will become intolerant of challenges.[10]:93[11]:64 Combining a strong social identity with the state, increases the benefits, therefore it is likely persecution from that social group will increase.[6]:8 Legal restriction from the state relies on social cooperation, so the state in its turn must protect the social group which supports it, increasing the likelihood of persecution from the state as well.[6]:9 Grim and Finke say their studies indicate that the higher the degree of religious freedom, the lower the degree of violent religious persecution.[6]:3 "When religious freedoms are denied through the regulation of religious profession or practice, violent religious persecution and conflict increase."[6]:6

Perez Zagorin writes that, "According to some philosophers, tolerance is a moral virtue; if this is the case, it would follow that intolerance is a vice. But virtue and vice are qualities solely of individuals, and intolerance and persecution [in the Christian Middle Ages] were social and collective phenomena sanctioned by society and hardly questioned by anyone. Religious intolerance and persecution, therefore, were not seen as vices, but as necessary and salutary for the preservation of religious truth and orthodoxy and all that was seen to depend upon them."[12] This view of persecution is not limited to the Middle Ages. As Christian R. Raschle[13] and Jitse H. F. Dijkstra,[14] say: "Religious violence is a complex phenomenon that exists in all places and times."[15]:4,6

In the ancient societies of Egypt, Greece and Rome, torture was an accepted aspect of the legal system.[16]:22 Gillian Clark says violence was taken for granted in the fourth century as part of both war and punishment; torture from the carnifex, the professional torturer of the Roman legal system, was an accepted part of that system.[17]:137 Except for a few rare exceptions, such as the Persian empire under Cyrus and Darius,[18] Denis Lacorne says that examples of religious tolerance in ancient societies, "from ancient Greece to the Roman empire, medieval Spain to the Ottoman Empire and the Venetian Republic", are not examples of tolerance in the modern sense of the term.[19]

The sociological view indicates religious intolerance and persecution are largely social processes that are determined more by the context the social community exists within than anything else.[20][10]:94[4]:19,24 When governments insure equal freedom for all, there is less persecution.[6]:8

Statistics

The following statistics from Pew Research Center show that Jews, Hindus and Muslims are "most likely to live in countries where their groups experience harassment":[21] According to a 2019 report, government restrictions and social hostilities toward religion have risen in 187 countries.[22]

| Group | Probability that a religious lives in a country where persecution of the group occurred in 2015 |

Number of countries where the group was persecuted in 2015 |

Number of countries where the group was persecuted by the government in 2015 |

Number of countries where the group experienced government restrictions and/or social hostilities in 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jews | 99% | 74 | 43 | 87 |

| Hindus | 99% | 18 | 14 | 23 |

| Muslims | 97% | 125 | 106 | 140 |

| Other religions | 85% | 50 | 44 | 50 |

| Folk religions | 80% | 32 | 16 | 38 |

| Christians | 78% | 128 | 97 | 143 |

| Buddhists | 72% | 7 | 5 | 19 |

| Unaffiliated | 14 | 9 | 23 |

Forms

Cleansing

"Religious cleansing" is a term that is sometimes used to refer to the removal of a population from a certain territory based on its religion.[23] Throughout antiquity, population cleansing was largely motivated by economic and political factors, although ethnic factors occasionally played a role.[23] During the Middle Ages, population cleansing took on a largely religious character.[23] The religious motivation lost much of its salience early in the modern era, although until the 18th century ethnic enmity in Europe remained couched in religious terms.[23] Richard Dawkins has argued that references to ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia and Iraq are euphemisms for what should more accurately be called religious cleansing.[24] According to Adrian Koopman, the widespread use of the term ethnic cleansing in such cases suggests that in many situations there is confusion between ethnicity and religion.[24]

Ethnicity

Other acts of violence, such as war, torture, and ethnic cleansing not aimed at religion in particular, may nevertheless take on the qualities of religious persecution when one or more of the parties involved are characterized by religious homogeneity; an example being when conflicting populations that belong to different ethnic groups often also belong to different religions or denominations. The difference between religious and ethnic identity might sometimes be obscure (see Ethnoreligious); cases of genocide in the 20th century cannot be explained in full by citing religious differences. Still, cases such as the Greek genocide, the Armenian Genocide, and the Assyrian Genocide are sometimes seen as religious persecution and blur the lines between ethnic and religious violence.

Since the Early modern period, an increasing number of religious cleansings were entwined with ethnic elements.[25] Since religion is an important or central marker of ethnic identity, some conflicts can best be described as "ethno-religious conflicts".[26]

Nazi antisemitism provides another example of the contentious divide between ethnic and religious persecution, because Nazi propaganda tended to construct its image of Jews as belonging to a race, it de-emphasized Jews as being defined by their religion. In keeping with what they were taught in Nazi propaganda, the perpetrators of the Holocaust made no distinction between secular Jews, atheistic Jews, orthodox Jews and Jews who had converted to Christianity. The Nazis also persecuted the Catholic Church in Germany and Poland.

Persecution for heresy and blasphemy

The persecution of beliefs that are deemed schismatic is one thing; the persecution of beliefs that are deemed heretical or blasphemous is another. Although a public disagreement on secondary matters might be serious enough, it has often only led to religious discrimination. A public renunciation of the core elements of a religious doctrine under the same circumstances would, on the other hand, have put one in far greater danger. While dissenters from the official Church only faced fines and imprisonment in Protestant England, six people were executed for heresy or blasphemy during the reign of Elizabeth I, and two more were executed in 1612 under James I.[27]

Similarly, heretical sects like Cathars, Waldensians and Lollards were brutally suppressed in Western Europe, while, at the same time, Catholic Christians lived side by side with 'schismatic' Orthodox Christians after the East-West Schism in the borderlands of Eastern Europe.[28]

Persecution for political reasons

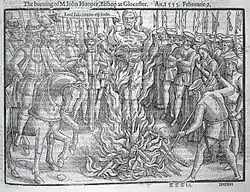

More than 300 Roman Catholics were put to death for treason by English governments between 1535 and 1681, thus they were executed for secular rather than religious offenses.[27] In 1570, Pope Pius V issued his papal bull Regnans in Excelsis, which absolved Catholics from their obligations to the government.[29] This dramatically worsened the persecution of Catholics in England. English governments continued to fear the fictitious Popish Plot. The 1584 Parliament of England, declared in "An Act against Jesuits, seminary priests, and such other like disobedient persons" that the purpose of Jesuit missionaries who had come to Britain was "to stir up and move sedition, rebellion and open hostility".[30] Consequently, Jesuit priests like Saint John Ogilvie were hanged. This somehow contrasts with the image of the Elizabethan era as the time of William Shakespeare, but compared to the antecedent Marian Persecutions there is an important difference to consider. Mary I of England had been motivated by a religious zeal to purge heresy from her land, and during her short reign from 1553 to 1558 about 290 Protestants[31] had been burned at the stake for heresy, whereas Elizabeth I of England "acted out of fear for the security of her realm."[32]

By location

The descriptive use of the term religious persecution is rather difficult. Religious persecution has occurred in different historical, geographical and social contexts since at least antiquity. Until the 18th century, some groups were nearly universally persecuted for their religious views, such as atheists,[33] Jews[34] and Zoroastrians.[35]

Roman Empire

Early Christianity also came into conflict with the Roman Empire, and it may have been more threatening to the established polytheistic order than Judaism had been, because of the importance of evangelism in Christianity. Under Nero, the Jewish exemption from the requirement to participate in public cults was lifted and Rome began to actively persecute monotheists. This persecution ended in 313 AD with the Edict of Milan, and Christianity was made the official religion of the empire in 380 AD. By the eighth century Christianity had attained a clear ascendancy across Europe and neighboring regions, and a period of consolidation began which was marked by the pursuit of heretics, heathens, Jews, Muslims, and various other religious groups.

Early modern England

One period of religious persecution which has been extensively studied is early modern England, since the rejection of religious persecution, now common in the Western world, originated there. The English 'Call for Toleration' was a turning point in the Christian debate on persecution and toleration, and early modern England stands out to the historians as a place and time in which literally "hundreds of books and tracts were published either for or against religious toleration."[36]

The most ambitious chronicle of that time is W.K.Jordan's magnum opus The Development of Religious Toleration in England, 1558-1660 (four volumes, published 1932-1940). Jordan wrote as the threat of fascism rose in Europe, and this work is seen as a defense of the fragile values of humanism and tolerance.[37] More recent introductions to this period are Persecution and Toleration in Protestant England, 1558–1689 (2000) by John Coffey and Charitable hatred. Tolerance and intolerance in England, 1500-1700 (2006) by Alexandra Walsham. To understand why religious persecution has occurred, historians like Coffey "pay close attention to what the persecutors said they were doing."[36]

Ecclesiastical dissent and civil tolerance

No religion is free from internal dissent, although the degree of dissent that is tolerated within a particular religious organization can strongly vary. This degree of diversity tolerated within a particular church is described as ecclesiastical tolerance,[38] and is one form of religious toleration. However, when people nowadays speak of religious tolerance, they most often mean civil tolerance, which refers to the degree of religious diversity that is tolerated within the state.

In the absence of civil toleration, someone who finds himself in disagreement with his congregation doesn't have the option to leave and chose a different faith - simply because there is only one recognized faith in the country (at least officially). In modern western civil law any citizen may join and leave a religious organization at will; In western societies, this is taken for granted, but actually, this legal separation of Church and State only started to emerge a few centuries ago.

In the Christian debate on persecution and toleration, the notion of civil tolerance allowed Christian theologians to reconcile Jesus' commandment to love one's enemies with other parts of the New Testament that are rather strict regarding dissent within the church. Before that, theologians like Joseph Hall had reasoned from the ecclesiastical intolerance of the early Christian church in the New Testament to the civil intolerance of the Christian state.[39]

Religious uniformity in early modern Europe

By contrast to the notion of civil tolerance, in early modern Europe the subjects were required to attend the state church; This attitude can be described as territoriality or religious uniformity, and its underlying assumption is brought to a point by a statement of the Anglican theologian Richard Hooker: "There is not any man of the Church of England but the same man is also a member of the [English] commonwealth; nor any man a member of the commonwealth, which is not also of the Church of England."[40]

Before a vigorous debate about religious persecution took place in England (starting in the 1640s), for centuries in Europe, religion had been tied to territory. In England there had been several Acts of Uniformity; in continental Europe the Latin phrase "cuius regio, eius religio" had been coined in the 16th century and applied as a fundament for the Peace of Augsburg (1555). It was pushed to the extreme by absolutist regimes, particularly by the French kings Louis XIV and his successors. It was under their rule that Catholicism became the sole compulsory allowed religion in France and that the huguenots had to massively leave the country. Persecution meant that the state was committed to secure religious uniformity by coercive measures, as eminently obvious in a statement of Roger L'Estrange: "That which you call persecution, I translate Uniformity".[41]

However, in the 17th century writers like Pierre Bayle, John Locke, Richard Overton and Roger William broke the link between territory and faith, which eventually resulted in a shift from territoriality to religious voluntarism.[42] It was Locke who, in his Letter Concerning Toleration, defined the state in purely secular terms:[43] "The commonwealth seems to me to be a society of men constituted only for the procuring, preserving, and advancing their own civil interests."[44] Concerning the church, he went on: "A church, then, I take to be a voluntary society of men, joining themselves together of their own accord."[44] With this treatise, John Locke laid one of the most important intellectual foundations of the separation of church and state, which ultimately led to the secular state.

Russia

The Bishop of Vladimir Feodor turned some people into slaves, others were locked in prison, cut their heads, burnt eyes, cut tongues or crucified on walls. Some heretics were executed by burning them alive. According to an inscription of Khan Mengual-Temir, Metropolitan Kiril was granted the right to heavily punish with death for blasphemy against the Orthodox Church or breach of ecclesiastical privileges. He advised all means of destruction to be used against heretics, but without bloodshed, in the name of 'saving souls'. Heretics were drowned. Novgorod Bishop Gennady Gonzov turned to Tsar Ivan III requesting the death of heretics. Gennady admired the Spanish inquisitors, especially his contemporary Torquemada, who for 15 years of inquisition activity burned and punished thousands of people. As in Rome, persecuted fled to depopulated areas. The most terrible punishment was considered an underground pit, where rats lived. Some people had been imprisoned and tied to the wall there, and untied after their death.[45] Old Believers were persecuted and executed, the order was that even those renouncing completely their beliefs and baptized in the state Church to be lynched without mercy. The writer Lomonosov opposed the religious teachings and by his initiative a scientific book against them was published. The book was destroyed, the Russian synod insisted Lomonosov's works to be burned and requested his punishment.

...were cutting heads, hanging, some by the neck, some by the foot, many of them were stabbed with sharp sticks and impaled on hooks. This included the tethering to a ponytail, drowning and freezing people alive in lakes. The winners did not spare even the sick and the elderly, taking them out of the monastery and throwing them mercilessly in icy 'vises'. The words step back, the pen does not move, in eternal darkness the ancient Solovetsky monastery is going. Of the more than 500 people, only a few managed to avoid the terrible court.[46]

Contemporary

.jpg.webp)

Although his book was written before the September 11 attacks, John Coffey explicitly compares the English fear of the Popish Plot to Islamophobia in the contemporary Western world.[47] Among the Muslims imprisoned in the Guantanamo Bay detention camp there also were Mehdi Ghezali and Murat Kurnaz who could not have been found to have any connections with terrorism, but had traveled to Afghanistan and Pakistan because of their religious interests.

The United States submits an annual report on religious freedom and persecution to the Congress containing data it has collected from U.S. embassies around the world in collaboration with the Office of International Religious Freedom and other relevant U.S. government and non-governmental institutions. The data is available to the public.[48] The 2018 study details, country by country, the violations of religious freedom taking place in approximately 75% of the 195 countries in the world. Between 2007 and 2017, the PEW organization[49] found that "Christians experienced harassment by governments or social groups in the largest number of countries"—144 countries—but that it is almost equal to the number of countries (142) in which Muslims experience harassment.[49] PEW has published a caution concerning the interpretation of these numbers: "The Center's recent report ... does not attempt to estimate the number of victims in each country... it does not speak to the intensity of harassment..." [50]

There are no religious groups free of harassment somewhere in the contemporary world. Klaus Wetzel, an expert on religious persecution for the German Bundestag, the House of Lords, the US House of Representatives, the European Parliament, and the International Institute for Religious Freedom, explains that "In around a quarter of all countries in the world, the restrictions imposed by governments, or hostilities towards one or more religious groups, are high or very high. Some of the most populous countries in the world belong to this group, such as China, India, Indonesia and Pakistan. Therefore, around three quarters of the world's population live in them."[51]

At the symposium on law and religion in 2014, Michelle Mack said: "Despite what appears to be a near-universal expression of commitment to religious human rights, the frequency-and severity-of religious persecution worldwide is staggering. Although it is impossible to determine with certainty the exact numbers of people persecuted for their faith or religious affiliation, it is unquestioned that "violations of freedom of religion and belief, including acts of severe persecution, occur with fearful frequency."[52]:462,note 24 She quotes Irwin Colter, human rights advocate and author as saying "[F]reedom of religion remains the most persistently violated human right in the annals of the species."[53]

Despite the ubiquitous nature of religious persecution, the traditional human rights community typically chooses to emphasize "more tangible encroachments on human dignity," such as violations based on race, gender, and class using national, ethnic, and linguistic groupings instead.[54]

By religion

Persecutions of atheists

Used before the 18th century as an insult,[55] atheism was punishable by death in ancient Greece as well as in the Christian and Muslim worlds during the Middle Ages. Today, atheism is punishable by death in 13 countries (Afghanistan, Iran, Malaysia, the Maldives, Mauritania, Nigeria, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen), all of them Muslim, while "the overwhelming majority" of the 192 United Nations member countries "at best discriminate against citizens who have no belief in a god and at worst they can jail them for offences which are dubbed blasphemy".[56][57]

State atheism

State atheism has been defined by David Kowalewski as the official "promotion of atheism" by a government, typically by the active suppression of religious freedom and practice.[58] It is a misnomer which is used in reference to a government's anti-clericalism, its opposition to religious institutional power and influence, whether it is real or alleged, in all aspects of public and political life, including the involvement of religion in the everyday life of the citizen.[59]

State atheism was first practiced for a brief period in Revolutionary France and later it was practiced in Revolutionary Mexico and Communist states. The Soviet Union had a long history of state atheism,[60] in which social success largely required individuals to profess atheism, stay away from churches and even vandalize them; this attitude was especially militant during the middle Stalinist era from 1929 to 1939.[61][62][63] The Soviet Union attempted to suppress religion over wide areas of its influence, including places like central Asia,[64] and the post-World War II Eastern bloc. One state within that bloc, the Socialist People's Republic of Albania under Enver Hoxha, went so far as to officially ban all religious practices.[65]

Persecutions of Jews

A major component of Jewish history, persecutions have been committed by Seleucids,[66] ancient Greeks,[34] ancient Romans, Christians (Catholics, Orthodox and Protestant), Muslims, Nazis, etc. Some of the most important events which constitute this history include the 1066 Granada massacre, the Rhineland massacres (by Catholics but against papal orders, see also : Sicut Judaeis), the Alhambra Decree after the Reconquista and the establishment of the Spanish Inquisition, the publication of On the Jews and Their Lies by Martin Luther which furthered Protestant anti-Judaism and was later used to strengthen German antisemitism and justify pogroms and the Holocaust.

According to FBI statistics, a majority of all religiously motivated hate crimes in the United States are targeted at Jews. In 2018, anti-Jewish hate crimes represented 57.8% of all religiously motivated hate crimes, while anti-Muslim hate crimes, which were the second most common, represented 14.5%.[67]

Persecution of Muslims

Persecution of Muslims is the religious persecution that is inflicted upon followers of the Islamic faith. In the early days of Islam at Mecca, the new Muslims were often subjected to abuse and persecution by the pagan Meccans (often called Mushrikin: the unbelievers or polytheists).[68][69] Muslims were persecuted by Meccans at the time of prophet Muhammed.

Currently, Muslims face religious restrictions in 142 countries according to the PEW report on rising religious restrictions around the world.[70] According to the US State Department's 2019 freedom of religion report, the Central African Republic remains divided between the Christian anti-Balaka and the predominantly Muslim ex-Seleka militia forces with many Muslim communities displaced and not allowed to practice their religion freely.[71] In Nigeria, "conflicts between predominantly Muslim Fulani herdsmen and predominantly Christian farmers in the North Central states continued throughout 2019."[72]

In China, General Secretary Xi Jinping has decreed that all members of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) must be “unyielding Marxist atheists.” In Xinjiang province, the government enforced restrictions on Muslims.

The U.S. government estimates that since April 2017, the Chinese government arbitrarily detained more than one million Uighurs, ethnic Kazakhs, Hui, and members of other Muslim groups, as well as Uighur Christians, in specially built or converted internment camps in Xinjiang and subjected them to forced disappearance, political indoctrination, torture, physical and psychological abuse, including forced sterilization and sexual abuse, forced labor, and prolonged detention without trial because of their religion and ethnicity. There were reports of individuals dying as a result of injuries sustained during interrogations...

"Authorities in Xinjiang restricted access to mosques and barred youths from participating in religious activities, including fasting during Ramadan... maintained extensive and invasive security and surveillance... forcing Uighurs and other ethnic and religious minorities to install spyware on their mobile phones and accept government officials and CCP members living in their homes. Satellite imagery and other sources indicated the government destroyed mosques, cemeteries, and other religious sites... The government sought the forcible repatriation of Uighur and other Muslims from foreign countries and detained some of those who returned... Anti-Muslim speech in social media remained widespread."[73]

Shia-Sunni conflicts persist. Indonesia is approximately 87% Sunni Muslim, and "Shia and Ahmadi Muslims reported feeling under constant threat." Anti-Shia rhetoric was common throughout 2019 in some online media outlets and on social media."[74]

In Saudi Arabia, the government "is based largely on sharia as interpreted by the Hanbali school of Sunni Islamic jurisprudence. Freedom of religion is not provided under the law." In January and May 2019, police raided predominantly Shia villages in the al-Qatif Governorate... In April the government executed 37 citizens ...33 of the 37 were from the country's minority Shia community and had been convicted following what they stated were unfair trials for various alleged crimes, including protest-related offenses... Authorities detained ... three Shia Muslims who have written in the past on the discrimination faced by Shia Muslims, with no official charges filed; they remained in detention at year's end... Instances of prejudice and discrimination against Shia Muslims continued to occur..."[75]

Islamophobia continues. In Finland, "A report by the European Commission Against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) said hate crimes and intolerant speech in public discourse, principally against Muslims and asylum seekers (many of whom belong to religious minorities), had increased in recent years... A Finns Party politician publicly compared Muslim asylum seekers to an invasive species." There were several demonstrations by neo-Nazis and nativist groups in 2019. One neo-Nazi group, the NRM (the Nordic Resistance Movement), "continued to post anti-Muslim and anti-Semitic statements online and demonstrated with the anti-immigrant group Soldiers of Odin."[76]

The ongoing Rohingya genocide has resulted in over 25,000 deaths from 2016 to present.[77][78] Over 700,000 refugees have been sent abroad since 2017.[79] Gang rapes and other acts of sexual violence, mainly against Rohingya women and girls, have also been committed by the Rakhine Buddhists and the Burmese military's soldiers, along with the arson of Rohingya homes and mosques, as well as many other human rights violations.[80]

Persecution of Hindus

Hindus have experienced historical and current religious persecution and systematic violence. These occurred in the form of forced conversions, documented massacres, demolition and desecration of temples, as well as the destruction of educational centres.

Four major eras of persecution of Hindus can be discerned:

- Violence of Muslim-rulers against the Indian population, driven by rejection of Non-Islamic religions;

- Violence of European Colonial rulers;

- Violence against Hindus in the context of the Indian-Pakistan conflict;

- Other contemporary cases of violence against Hindus worldwide.

Hindus have been one of the targeted and persecuted minorities in Pakistan. Militancy and sectarianism has been rising in Pakistan since the 1990s, and the religious minorities have "borne the brunt of the Islamist's ferocity" suffering "greater persecution than in any earlier decade", states Farahnaz Ispahani – a Public Policy Scholar at the Wilson Center. This has led to attacks and forced conversion of Hindus, and other minorities such as Christians.[83][84][85] According to Tetsuya Nakatani – a Japanese scholar of Cultural Anthropology specializing in South Asia refugee history, after the mass exodus of Hindu, Sikh and other non-Muslim refugees during the 1947 partition of British India, there were several waves of Hindu refugees arrival into India from its neighbors.[86] The fearful and persecuted refugee movements were often after various religious riots between 1949 and 1971 that targeted non-Muslims within West Pakistan or East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). The status of these persecuted Hindu refugees in India has remained in a political limbo.[86]

Similar concerns about religious persecution of Hindu and other minorities in Bangladesh have also been expressed. The USCIRF notes hundreds of cases of "killings, attempted killings, death threats, assaults, rapes, kidnappings, and attacks on homes, businesses, and places of worship" on religious minorities in 2017.[87] Since the 1990s, Hindus have been a persecuted minority in Afghanistan, and a subject of "intense hate" with the rise of religious fundamentalism in Afghanistan.[88] Their "targeted persecution" triggered an exodus and forced them to seek asylum.[89] The persecuted Hindus have remained stateless and without citizenship rights in India, since it has historically lacked any refugee law or uniform policy for persecuted refugees, state Ashish Bose and Hafizullah Emadi.[88][90]

The Bangladesh Liberation War (1971) resulted in one of the largest genocides of the 20th century. While estimates of the number of casualties was 3,000,000, it is reasonably certain that Hindus bore a disproportionate brunt of the Pakistan Army's onslaught against the Bengali population of what was East Pakistan. An article in Time magazine dated 2 August 1971, stated "the Hindus, who account for three-fourths of the refugees and a majority of the dead, have borne the brunt of the Muslim military hatred."[91] Senator Edward Kennedy wrote in a report that was part of United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations testimony dated 1 November 1971, "Hardest hit have been members of the Hindu community who have been robbed of their lands and shops, systematically slaughtered, and in some places, painted with yellow patches marked "H". All of this has been officially sanctioned, ordered and implemented under martial law from Islamabad". In the same report, Senator Kennedy reported that 80% of the refugees in India were Hindus and according to numerous international relief agencies such as UNESCO and World Health Organization the number of East Pakistani refugees at their peak in India was close to 10 million. Given that the Hindu population in East Pakistan was around 11 million in 1971, this suggests that up to 8 million, or more than 70% of the Hindu population had fled the country.The Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Sydney Schanberg covered the start of the war and wrote extensively on the suffering of the East Bengalis, including the Hindus both during and after the conflict. In a syndicated column "The Pakistani Slaughter That Nixon Ignored", he wrote about his return to liberated Bangladesh in 1972. "Other reminders were the yellow "H"s the Pakistanis had painted on the homes of Hindus, particular targets of the Muslim army" (by "Muslim army", meaning the Pakistan Army, which had targeted Bengali Muslims as well), (Newsday, 29 April 1994).

Hindus constitute approximately 0.5% of the total population of the United States. Hindus in the US enjoy both de jure and de facto legal equality. However, a series of attacks were made on people Indian origin by a street gang called the "Dotbusters" in New Jersey in 1987, the dot signifying the Bindi dot sticker worn on the forehead by Indian women.[92] The lackadaisical attitude of the local police prompted the South Asian community to arrange small groups all across the state to fight back against the street gang. The perpetrators have been put to trial. On 2 January 2012, a Hindu worship center in New York City was firebombed.[93] The Dotbusters were primarily based in New York and New Jersey and committed most of their crimes in Jersey City. A number of perpetrators have been brought to trial for these assaults. Although tougher anti-hate crime laws were passed by the New Jersey legislature in 1990, the attacks continued, with 58 cases of hate crimes against Indians in New Jersey reported in 1991.[94]

In Bangladesh, on 28 February 2013, the International Crimes Tribunal sentenced Delwar Hossain Sayeedi, the Vice President of the Jamaat-e-Islami to death for the war crimes committed during the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War. Following the sentence, the Hindus were attacked in different parts of the country. Hindu properties were looted, Hindu houses were burnt into ashes and Hindu temples were desecrated and set on fire.[95][96]

Persecution of Christians

The persecution of Christians is, for the most part, historical.[97] Even from the beginnings of the religion as a movement within Judaism, Early Christians were persecuted for their faith at the hands of both Jews and the Roman Empire, which controlled much of the areas where Christianity was first distributed. This continued from the first century until the early fourth, when the religion was legalized by the Edict of Milan, eventually becoming the State church of the Roman Empire. Many Christians fled persecution in the Roman empire by emigrating to the Persian empire where for a century and a half after Constantine's conversion, they were persecuted under the Sassanids, with thousands losing their lives.[98]:76 Christianity continued to spread through "merchants, slaves, traders, captives and contacts with Jewish communities" as well as missionaries who were often killed for their efforts.[98]:97, 131, 224–225, 551 This killing continued into the Early modern period beginning in the fifteenth century, to the Late modern period of the twentieth century, and into the contemporary period today.[99][100][101][102][103]

In contemporary society, Christians are persecuted in Iran and other parts of the Middle East, for example, for proselytising, which is illegal there.[106][107][108] Of the 100–200 million Christians alleged to be under assault, the majority are persecuted in Muslim-majority nations.[109] Every year, the Christian non-profit organization Open Doors publishes the World Watch List – a list of the top 50 countries which it designates as the most dangerous for Christians. Violence against Christians is increasing by Sangh Parivar agendas. Anti-Christian violence is seen in all Christian majority states like Nagaland (90% Christian state of India), Meghalaya [90% Christian ], and Mizoram where Christians were majority is attacked by Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. Also, Anti-Christian violence in India is religiously-motivated violence against Christians in India. Violence against Christians has been seen by the organization Human Rights Watch as a tactic used to meet political ends by Hindutva. The acts of violence include arson of churches, conversion of Christians by force and threats of physical violence, sexual assaults, murder of Christian priests, and destruction of Christian schools, colleges, and cemeteries.

The 2018 World Watch List has the following countries as its top ten: North Korea, and Eritrea, whose Christian and Muslim religions are controlled by the state, and Afghanistan, Myanmar, Somalia, Sudan, Pakistan, Libya, Iraq, Yemen, India and Iran, which are all predominantly other religion.[110] Due to the large number of Christian majority countries, differing groups of Christians are harassed and persecuted in Christian countries such as Eritrea[111] and Mexico[112] more often than in Muslim countries, although not in greater numbers.[113]

There are low to moderate restrictions on religious freedom in three-quarters of the world's countries, with high and very high restrictions in a quarter of them, according to the State Department's report on religious freedom and persecution delivered annually to Congress.[114] The Internationale Gesellschaft für Menschenrechte[115] — the International Society for Human Rights — in Frankfurt, Germany is a non-governmental organization with 30,000 members from 38 countries who monitor human rights. In September 2009, then chairman Martin Lessenthin,[116] issued a report estimating that 80% of acts of religious persecution around the world were aimed at Christians at that time.[117][118] According to the World Evangelical Alliance, over 200 million Christians are denied fundamental human rights solely because of their faith.[119]

A report released by the UK's Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, and a report by the PEW organization studying worldwide restrictions of religious freedom, both have Christians suffering in the highest number of countries, rising from 125 in 2015 to 144 as of 2018.[120][49][121] PEW has published a caution concerning the interpretation of these numbers: "The Center's recent report ... does not attempt to estimate the number of victims in each country... it does not speak to the intensity of harassment..."[50] France, who restricts the wearing of the hijab, is counted as a persecuting country equally with Nigeria and Pakistan where, according to the Global Security organization, Christians have been killed for their faith.[122]

In December 2016, the Center for the Study of Global Christianity (CSGC) at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in Massachusetts, published a statement that "between 2005 and 2015 there were 900,000 Christian martyrs worldwide — an average of 90,000 per year, marking a Christian as persecuted every 8 minutes."[123][124] However, the BBC has reported that others such as Open Doors and the International Society for Human Rights have disputed that number's accuracy.[125][51][126] Gina Zurlo, the CSGC's assistant director, explained that two-thirds of the 90,000 died in tribal conflicts, and nearly half were victims of the civil war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[127] Klaus Wetzel, an internationally recognized expert on religious persecution, explains that Gordon-Conwell defines Christian martyrdom in the widest possible sense, while Wetzel and Open doors and others such as The International Institute for Religious Freedom (IIRF) use a more restricted definition: 'those who are killed, who would not have been killed, if they had not been Christians.'[128] Open Doors documents that anti-Christian sentiment is presently based on direct evidence and makes conservative estimates based on indirect evidence.[129] This approach dramatically lowers the numerical count. Open Doors says that, while numbers fluctuate every year, they estimate 11 Christians are currently dying for their faith somewhere in the world every day.[130]

Despite disputes and difficulties with numbers, there are indicators such as the Danish National Research Database, that Christians are, as of 2019, the most persecuted religious group in the world.[131][132][133][134]

Persecutions of Sikhs

According to Ashish Bose – a Population Research scholar, Sikhs and Hindus were well integrated in Afghanistan till the Soviet invasion when their economic condition worsened. Thereafter, they became a subject of "intense hate" with the rise of religious fundamentalism in Afghanistan.[88] Their "targeted persecution" triggered an exodus and forced them to seek asylum.[89][88] Many of them started arriving in and after 1992 as refugees in India, with some seeking asylum in the United Kingdom and other western countries.[88][89] Unlike the arrivals in the West, the persecuted Sikh refugees who arrived in India have remained stateless and lived as refugees because India has historically lacked any refugee law or uniform policy for persecuted refugees, state Ashish Bose and Hafizullah Emadi.[88][90]

On 7 November 1947, thousands of Hindus and Sikhs were targeted in the Rajouri Massacre in Jammu and Kashmir princely state. It is estimated 30,000+ Hindus and Sikhs were either killed, abducted or injured.[135][136][137] In one instance, on 12 November 1947 alone between 3000 and 7000 were killed.[138] A few weeks after on 25 November 1947, tribal forces began the 1947 Mirpur Massacre of thousands more Hindus and Sikhs. An estimated 20,000+ died in the massacre.[139][140][141][142][143][144][145][146]

The 1984 anti-Sikhs riots were a series of pogroms[147][148][149][150] directed against Sikhs in India, by anti-Sikh mobs, in response to the assassination of Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards. There were more than 8,000[151] deaths, including 3,000 in Delhi.[149] In June 1984, during Operation Blue Star, Indira Gandhi ordered the Indian Army to attack the Golden Temple and eliminate any insurgents, as it had been occupied by Sikh separatists who were stockpiling weapons. Later operations by Indian paramilitary forces were initiated to clear the separatists from the countryside of Punjab state.[152]

The violence in Delhi was triggered by the assassination of Indira Gandhi, India's prime minister, on 31 October 1984, by two of her Sikh bodyguards in response to her actions authorising the military operation. After the assassination following Operation Blue Star, many Indian National Congress workers including Jagdish Tytler, Sajjan Kumar and Kamal Nath were accused of inciting and participating in riots targeting the Sikh population of the capital. The Indian government reported 2,700 deaths in the ensuing chaos. In the aftermath of the riots, the Indian government reported 20,000 had fled the city, however the People's Union for Civil Liberties reported "at least" 1,000 displaced persons.[153] The most affected regions were the Sikh neighbourhoods in Delhi. The Central Bureau of Investigation, the main Indian investigating agency, is of the opinion that the acts of violence were organized with the support from the then Delhi police officials and the central government headed by Indira Gandhi's son, Rajiv Gandhi.[154] Rajiv Gandhi was sworn in as Prime Minister after his mother's death and, when asked about the riots, said "when a big tree falls (Mrs. Gandhi's death), the earth shakes (occurrence of riots)" thus trying to justify communal strife.[155]

There are allegations that the Indian National Congress government at that time destroyed evidence and shielded the guilty. The Asian Age front-page story called the government actions "the Mother of all Cover-ups"[156][157] There are allegations that the violence was led and often perpetrated by Indian National Congress activists and sympathisers during the riots.[158] The government, then led by the Congress, was widely criticised for doing very little at the time, possibly acting as a conspirator. The conspiracy theory is supported by the fact that voting lists were used to identify Sikh families. Despite their communal conflict and riots record, the Indian National Congress claims to be a secular party.

Persecution of Buddhists

Persecution of Buddhists was a widespread phenomenon throughout the history of Buddhism, lasting to this day. This begun as early as the 3rd century AD, by the Zoroastrian high priest Kirder of the Sasanian Empire.

Anti-Buddhist sentiments in Imperial China between the 5th and 10th century led to the Four Buddhist Persecutions in China of which the Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution of 845 was probably the most severe. However Buddhism managed to survive but was greatly weakened. During the Northern Expedition, in 1926 in Guangxi, Kuomintang Muslim General Bai Chongxi led his troops in destroying Buddhist temples and smashing idols, turning the temples into schools and Kuomintang party headquarters.[159] During the Kuomintang Pacification of Qinghai, the Muslim General Ma Bufang and his army wiped out many Tibetan Buddhists in the northeast and eastern Qinghai, and destroyed Tibetan Buddhist temples.[160]

The Muslim invasion of the Indian subcontinent was the first great iconoclastic invasion into the Indian subcontinent.[161] According to William Johnston, hundreds of Buddhist monasteries and shrines were destroyed, Buddhist texts were burnt by the Muslim armies, monks and nuns killed during the 12th and 13th centuries in the Indo-Gangetic Plain region.[162] The Buddhist university of Nalanda was mistaken for a fort because of the walled campus. The Buddhist monks who had been slaughtered were mistaken for Brahmins according to Minhaj-i-Siraj.[163] The walled town, the Odantapuri monastery, was also conquered by his forces. Sumpa basing his account on that of Śākyaśrībhadra who was at Magadha in 1200, states that the Buddhist university complexes of Odantapuri and Vikramshila were also destroyed and the monks massacred.[164] Muslim forces attacked the north-western regions of the Indian subcontinent many times.[165] Many places were destroyed and renamed. For example, Odantapuri's monasteries were destroyed in 1197 by Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khilji and the town was renamed.[166] Likewise, Vikramashila was destroyed by the forces of Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khilji around 1200.[167] The sacred Mahabodhi Temple was almost completely destroyed by the Muslim invaders.[168][169] Many Buddhist monks fled to Nepal, Tibet, and South India to avoid the consequences of war.[170] Tibetan pilgrim Chöjepal (1179-1264), who arrived in India in 1234,[171] had to flee advancing Muslim troops multiple times, as they were sacking Buddhist sites.[172]

In Japan, the haibutsu kishaku during the Meiji Restoration (starting in 1868) was an event triggered by the official policy of separation of Shinto and Buddhism (or shinbutsu bunri). This caused great destruction to Buddhism in Japan, the destruction of Buddhist temples, images and texts took place on a large scale all over the country and Buddhist monks were forced to return to secular life.

During the 2012 Ramu violence in Bangladesh, a 25,000-strong Muslim mob set fire to at least five Buddhist temples and dozens of homes throughout the town and surrounding villages after seeing a picture of an allegedly desecrated Quran, which they claimed had been posted on Facebook by Uttam Barua, a local Buddhist man.[173][174]

Persecution of Jehovah's Witnesses

Political and religious animosity against Jehovah's Witnesses has at times led to mob action and government oppression in various countries. Their stance regarding political neutrality and their refusal to serve in the military has led to imprisonment of members who refused conscription during World War II and at other times where national service has been compulsory. Their religious activities are currently banned or restricted in some countries, including China, Vietnam, and some Islamic states.[175][176]

- In 1933, there were approximately 20,000 Jehovah's Witnesses in Nazi Germany,[177] of whom about 10,000 were imprisoned. Jehovah's Witnesses were brutally persecuted by the Nazis, because they refused military service and allegiance to Hitler's National Socialist Party.[178][179][180][181][182] Of those, 2,000 were sent to Nazi concentration camps, where they were identified by purple triangles;[180] as many as 1,200 died, including 250 who were executed.[183][184]

- In Canada during World War II, Jehovah's Witnesses were interned in camps[185] along with political dissidents and people of Chinese and Japanese descent.[186] Jehovah's Witnesses faced discrimination in Quebec until the Quiet Revolution, including bans on distributing literature or holding meetings.[187][188]

- In 1951, about 9,300 Jehovah's Witnesses in the Soviet Union were deported to Siberia as part of Operation North in April 1951.[189]

- In April 2017, the Supreme Court of Russia labeled Jehovah's Witnesses an extremist organization, banned its activities in Russia and issued an order to confiscate the organization's assets.[190]

Authors including William Whalen, Shawn Francis Peters and former Witnesses Barbara Grizzuti Harrison, Alan Rogerson and William Schnell have claimed the arrests and mob violence in the United States in the 1930s and 1940s were the consequence of what appeared to be a deliberate course of provocation of authorities and other religious groups by Jehovah's Witnesses. Whalen, Harrison and Schnell have suggested Rutherford invited and cultivated opposition for publicity purposes in a bid to attract dispossessed members of society, and to convince members that persecution from the outside world was evidence of the truth of their struggle to serve God.[191][192][193][194][195] Watch Tower Society literature of the period directed that Witnesses should "never seek a controversy" nor resist arrest, but also advised members not to co-operate with police officers or courts that ordered them to stop preaching, and to prefer jail rather than pay fines.[196]

Persecution of Baháʼís

The Baháʼís are Iran's largest religious minority, and Iran is the location of one of the seventh largest Baháʼí population in the world, with just over 251,100 as of 2010.[197] Baháʼís in Iran have been subject to unwarranted arrests, false imprisonment, beatings, torture, unjustified executions, confiscation and destruction of property owned by individuals and the Baháʼí community, denial of employment, denial of government benefits, denial of civil rights and liberties, and denial of access to higher education.

More recently, in the later months of 2005, an intensive anti-Baháʼí campaign was conducted by Iranian newspapers and radio stations. The state-run and influential Kayhan newspaper, whose managing editor is appointed by Iran's supreme leader, Ayatollah Khamenei The press in Iran, ran nearly three dozen articles defaming the Baháʼí Faith. Furthermore, a confidential letter sent on October 29, 2005 by the Chairman of the Command Headquarters of the Armed Forced in Iran states that the Supreme Leader of Iran, Ayatollah Khamenei has instructed the Command Headquarters to identify people who adhere to the Baháʼí Faith and to monitor their activities and gather any and all information about the members of the Baháʼí Faith. The letter was brought to the attention of the international community by Asma Jahangir, the Special Rapporteur of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights on freedom of religion or belief, in a March 20, 2006 press release .

In the press release the Special Rapporteur states that she "is highly concerned by information she has received concerning the treatment of members of the Baháʼí community in Iran." She further states that "The Special Rapporteur is concerned that this latest development indicates that the situation with regard to religious minorities in Iran is, in fact, deteriorating." .

Persecution of Druze

Historically the relationship between the Druze and Muslims has been characterized by intense persecution.[199][200][201] The Druze faith is often classified as a branch of Isma'ili. Even though the faith originally developed out of Ismaili Islam, most Druze do not identify as Muslims,[202][203][204] and they do not accept the five pillars of Islam.[205] The Druze have frequently experienced persecution by different Muslim regimes such as the Shia Fatimid Caliphate,[206] Mamluk,[207] Sunni Ottoman Empire,[208] and Egypt Eyalet.[209][210] The persecution of the Druze included massacres, demolishing Druze prayer houses and holy places and forced conversion to Islam.[211] Those were no ordinary killings in the Druze's narrative, they were meant to eradicate the whole community according to the Druze narrative.[212] Most recently, the Syrian Civil War, which began in 2011, saw persecution of the Druze at the hands of Islamic extremists.[213][214]

Ibn Taymiyya a prominent Muslim scholar muhaddith, dismissed the Druze as non-Muslims,[215] and his fatwa cited that Druzes: "Are not at the level of ′Ahl al-Kitāb (People of the Book) nor mushrikin (polytheists). Rather, they are from the most deviant kuffār (Infidel) ... Their women can be taken as slaves and their property can be seized ... they are be killed whenever they are found and cursed as they described ... It is obligatory to kill their scholars and religious figures so that they do not misguide others",[216] which in that setting would have legitimized violence against them as apostates.[217][218] Ottomans have often relied on Ibn Taymiyya religious ruling to justify their persecution of Druze.[219]

Persecution of Zoroastrians

Persecution of Zoroastrians is the religious persecution inflicted upon the followers of the Zoroastrian faith. The persecution of Zoroastrians occurred throughout the religion's history. The discrimination and harassment began in the form of sparse violence and forced conversions. Muslims are recorded to have destroyed fire temples. Zoroastrians living under Muslim rule were required to pay a tax called jizya.[220]

Zoroastrian places of worship were desecrated, fire temples were destroyed and mosques were built in their place. Many libraries were burned and much of their cultural heritage was lost. Gradually an increasing number of laws were passed which regulated Zoroastrian behavior and limited their ability to participate in society. Over time, the persecution of Zoroastrians became more common and widespread, and the number of believers decreased by force significantly.[220]

Most were forced to convert due to the systematic abuse and discrimination inflicted upon them by followers of Islam. Once a Zoroastrian family was forced to convert to Islam, the children were sent to an Islamic school to learn Arabic and study the teachings of Islam, as a result some of these people lost their Zoroastrian faith. However, under the Samanids, who were Zoroastrian converts to Islam, the Persian language flourished. On occasion, the Zoroastrian clergy assisted Muslims in attacks against those whom they deemed Zoroastrian heretics.[220]

A Zoroastrian astrologer named Mulla Gushtasp predicted the fall of the Zand dynasty to the Qajar army in Kerman. Because of Gushtasp's forecast, the Zoroastrians of Kerman were spared by the conquering army of Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar. Despite the aforementioned favorable incident, the Zoroastrians during the Qajar dynasty remained in agony and their population continued to decline. Even during the rule of Agha Mohammad Khan, the founder of the dynasty, many Zoroastrians were killed and some were taken as captives to Azerbaijan.[221] Zoroastrians regard the Qajar period as one of their worst.[222] During the Qajar Dynasty, religious persecution of the Zoroastrians was rampant. Due to the increasing contacts with influential Parsi philanthropists such as Maneckji Limji Hataria, many Zoroastrians left Iran for India. There, they formed the second major Indian Zoroastrian community known as the Iranis.[223]

Persecution of Falun Gong

The persecution of the Falun Gong spiritual practice began with campaigns initiated in 1999 by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to eliminate Falun Gong in China. It is characterised by multifaceted propaganda campaign, a program of enforced ideological conversion and re-education, and a variety of extralegal coercive measures such as arbitrary arrests, forced labor, and physical torture, sometimes resulting in death.[224]

There have being reports of Organ harvesting of Falun Gong practitioners in China. Several researchers—most notably Canadian human rights lawyer David Matas, former parliamentarian David Kilgour, and investigative journalist Ethan Gutmann—estimate that tens of thousands of Falun Gong prisoners of conscience have been killed to supply a lucrative trade in human organs and cadavers.[225]

Persecution of Serers

The persecution of the Serer people of Senegal, Gambia and Mauritania is multifaceted, and it includes both religious and ethnic elements. Religious and ethnic persecution of the Serer people dates back to the 11th century when King War Jabi usurped the throne of Tekrur (part of present-day Senegal) in 1030, and by 1035, introduced Sharia law and forced his subjects to submit to Islam.[226] With the assistance of his son (Leb), their Almoravid allies and other African ethnic groups who have embraced Islam, the Muslim coalition army launched jihads against the Serer people of Tekrur who refused to abandon Serer religion in favour of Islam.[227][228][229][230] The number of Serer deaths are unknown, but it triggered the exodus of the Serers of Tekrur to the south following their defeat, where they were granted asylum by the lamanes.[230] Persecution of the Serer people continued from the medieval era to the 19th century, resulting in the Battle of Fandane-Thiouthioune. From the 20th to the 21st centuries, persecution of the Serers is less obvious, nevertheless, they are the object of scorn and prejudice.[231][232]

Persecution of Copts

The persecution of Copts is a historical and ongoing issue in Egypt against Coptic Orthodox Christianity and its followers. It is also a prominent example of the poor status of Christians in the Middle East despite the religion being native to the region. Copts are the Christ followers in Egypt, usually Oriental Orthodox, who currently make up around 10% of the population of Egypt — the largest religious minority of that country.[lower-alpha 1] Copts have cited instances of persecution throughout their history and Human Rights Watch has noted "growing religious intolerance" and sectarian violence against Coptic Christians in recent years, as well as a failure by the Egyptian government to effectively investigate properly and prosecute those responsible.[237][238]

The Muslim conquest of Egypt took place in AD 639, during the Byzantine empire. Despite the political upheaval, Egypt remained a mainly Christian, but Copts lost their majority status after the 14th century,[239] as a result of the intermittent persecution and the destruction of the Christian churches there,[240] accompanied by heavy taxes for those who refused to convert.[241] From the Muslim conquest of Egypt onwards, the Coptic Christians were persecuted by different Muslims regimes,[242] such as the Umayyad Caliphate,[243] Abbasid Caliphate,[244][245][246] Fatimid Caliphate,[247][248][249] Mamluk Sultanate,[250][251] and Ottoman Empire; the persecution of Coptic Christians included closing and demolishing churches and forced conversion to Islam.[252][253][254]

Since 2011 hundreds of Egyptian Copts have been killed in sectarian clashes, and many homes, Churches and businesses have been destroyed. In just one province (Minya), 77 cases of sectarian attacks on Copts between 2011 and 2016 have been documented by the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights.[255] The abduction and disappearance of Coptic Christian women and girls also remains a serious ongoing problem.[256][257][258]

Persecution of Dogons

For almost 1000 years,[259] the Dogon people, an ancient tribe of Mali[260] had faced religious and ethnic persecution—through jihads by dominant Muslim communities.[259] These jihadic expeditions were to forced the Dogon to abandon their traditional religious beliefs for Islam. Such jihads caused the Dogon to abandon their original villages and moved up to the cliffs of Bandiagara for better defense and to escape persecution—often building their dwellings in little nooks and crannies.[259][261] In the early era of French colonialism in Mali, the French authorities appointed Muslim relatives of El Hadj Umar Tall as chiefs of the Bandiagara—despite the fact that the area has been a Dogon area for centuries.[262]

In 1864, Tidiani Tall, nephew and successor of the 19th century Senegambian jihadist and Muslim leader—El Hadj Umar Tall, chose Bandiagara as the capital of the Toucouleur Empire thereby exacerbating the inter-religious and inter-ethnic conflict. In recent years, the Dogon accused the Fulanis of supporting and sheltering Islamic terrorist groups like Al-Qaeda in Dogon country, leading to the creation of the Dogon militia Dan Na Ambassagou in 2016—whose aim is to defend the Dogon from systematic attacks. That resulted in the Ogossagou massacre of Fulanis in March 2019, and a Fula retaliation with the Sobane Da massacre in June of that year. In the wake of the Ogossagou massacre, the President of Mali, Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta and his government ordered the dissolution of Dan Na Ambassagou—whom they hold partly responsible for the attacks. The Dogon militia group denied any involvement in the massacre and rejected calls to disband.[263]

Persecution of Pagans & Heathens

Persecution of Philosophers

Philosophers throughout the history of philosophy have been held in courts and tribunals for various offenses, often as a result of their philosophical activity, and some have even been put to death. The most famous example of a philosopher being put on trial is the case of Socrates, who was tried for, amongst other charges, corrupting the youth and impiety.[264] Others include:

- Giordano Bruno - pantheist philosopher who was burned at the stake by the Roman Inquisition for his heretical religious views [265] and/or his cosmological views;[266]

- Tommaso Campanella - confined to a convent for his heretical views, namely, an opposition to the authority of Aristotle, and later imprisoned in a castle for 27 years during which he wrote his most famous works, including The City of the Sun;[267]

- Baruch Spinoza - Jewish philosopher who, at age 23, was put in cherem (similar to excommunication) by Jewish religious authorities for heresies such as his controversial ideas regarding the authenticity of the Hebrew Bible, which formed the foundations of modern biblical criticism, and the pantheistic nature of the Divine.[268] Prior to that, he had been attacked on the steps of the community synagogue by a knife-wielding assailant shouting "Heretic!",[269] and later his books were added to the Catholic Church's Index of Forbidden Books.

Persecution of Yazidis

The Persecution of Yazidis has been ongoing since at least the 10th century.[270][271] The Yazidi religion is regarded as devil worship by Islamists.[272] Yazidis have been persecuted by Muslim Kurdish tribes since the 10th century,[270] and by the Ottoman Empire from the 17th to the 20th centuries.[273] After the 2014 Sinjar massacre of thousands of Yazidis by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, Yazidis still face violence from the Turkish Armed Forces and its ally the Syrian National Army, as well as discrimination from the Kurdistan Regional Government. According to Yazidi tradition (based on oral traditions and folk songs), estimated that 74 genocides against the Yazidis have been carried out in the past 800 years.[274]

See also

- Christian privilege

- Cultural cleansing

- Discrimination

- Freedom of religion

- Human rights abuses

- Islamic religious police

- Conversion of non-Islamic places of worship into mosques

- List of Christian women of the patristic age

- Oppression

- Persecution

- Prejudice

- Price tag policy

- Religious abuse

- Religious discrimination

- Religious fanaticism

- Religious intolerance

- Religious pluralism

- Religious segregation

- Religious violence

Notes

- In 2017, the Wall Street Journal reported that "the vast majority of Egypt's estimated 9.5 million Christians, approximately 10% of the country's population, are Orthodox Copts."[233] In 2019, the Associated Press cited an estimate of 10 million Copts in Egypt.[234] In 2015, the Wall Street Journal reported: "The Egyptian government estimates about 5 million Copts, but the Coptic Orthodox Church says 15-18 million. Reliable numbers are hard to find but estimates suggest they make up somewhere between 6% and 18% of the population."[235] The CIA World Factbook reported a 2015 estimate that 10% of the Egyptian population is Christian (including both Copts and non-Copts).[236]

References

- David T. Smith (12 November 2015). Religious Persecution and Political Order in the United States. Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–. ISBN 978-1-107-11731-0.

"Persecution" in this study refers to violence or discrimination against members of a religious minority because of their religious affiliation. Persecution involves the most damaging expressions of prejudice against an out-group, going beyond verbal abuse and social avoidance.29 It refers to actions that are intended to deprive individuals of their political rights and force minorities to assimilate, leave, or live as second-class citizens. When these actions persistently happen over a period of time, and include large numbers of both perpetrators and victims, we may refer to them as being part of a "campaign" of persecution that usually has the goal of excluding the targeted minority from the polity.

- Nazila Ghanea-Hercock (11 November 2013). The Challenge of Religious Discrimination at the Dawn of the New Millennium. Springer. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-94-017-5968-7.

- Bateman, J. Keith. 2013. Don't call it persecution when it's not. Evangelical Missions Quarterly 49.1: 54-56, also p. 57-62.

- Kippenberg, Hans G. (2020). "1". In Raschle, Christian R.; Dijkstra, Jitse H. F. (eds.). Religious Violence in the Ancient World From Classical Athens to Late Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108849210.

- Jinkins, Michael. Christianity, Tolerance and Pluralism: A Theological Engagement with Isaiah Berlin's Social Theory. United Kingdom, Taylor & Francis, 2004. Chapter 3. no page #s available

- Grim, Brian J.; Finke, Roger (2010). The Price of Freedom Denied: Religious Persecution and Conflict in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139492416.

- Grim, BJ; Finke, R. (2007). "Religious Persecution in Cross-National Context: Clashing Civilizations or Regulated Religious Economies?". American Sociological Review. 72 (4): 633–658. doi:10.1177/000312240707200407. S2CID 145734744.

- Moore, R. I. (2007). The Formation of a Persecuting Society (second ed.). Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-2964-0.

- Gibson, James L. "James L. Gibson". Department of Political Science. Washington University in St.Louis Arts and Sciences.

Sidney W. Souers Professor of Government

- Gibson, James L., and Gouws, Amanda. Overcoming Intolerance in South Africa: Experiments in Democratic Persuasion. United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Heisig, James W.. Philosophers of Nothingness: An Essay on the Kyoto School. United States, University of Hawai'i Press, 2001.

- Zagorin, Perez (2013). How the Idea of Religious Toleration Came to the West. Princeton University Press. p. 16. ISBN 9781400850716.

- "Christian R Raschle". academia.edu. University of Motreal.

Université de Montréal, Histoire, Faculty Member

- "AIA Lecturer: Jitse H.F. Dijkstr". Lecture Program. Archaeological Institute of America.

- Raschle, Christian R.; Dijkstra, Jitse H. F., eds. (2020). Religious Violence in the Ancient World From Classical Athens to Late Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108849210.

- Stanley, Elizabeth (2008). Torture, Truth and Justice The Case of Timor-Leste. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781134021048.

- Clark, Gillian (2006). "11: Desires of the Hangman: Augustine on legitimized violence". In Drake, H. A. (ed.). Violence in Late Antiquity: Perceptions and Practices. Routledge. ISBN 978-0754654988.

- Ezquerra, Jaime Alvar. "History's first superpower sprang from ancient Iran". History Magazine. National Geographic. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- Lacorne, Denis (2019). The Limits of Tolerance: Enlightenment Values and Religious Fanaticism (Religion, Culture, and Public Life). Columbia University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0231187145.

- Dees, Richard H.. Trust and Toleration. N.p., Taylor & Francis, 2004. chapter 4. no page #s available

- "Jews, Hindus, Muslims most likely to live in countries where their groups experience harassment". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- "A Closer Look at How Religious Restrictions Have Risen Around the World". Pew Ressearch Center Religion & Public Life. PEW.

- Ken Booth (2012). The Kosovo Tragedy: The Human Rights Dimensions. Routledge. pp. 50–51. ISBN 9781136334764.

- Adrian Koopman (2016). "Ethnonyms". In Crole Hough (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Names and Naming. Oxford University Press. p. 256.

- Michael Mann (2005). The Dark Side of Democracy: Explaining Ethnic Cleansing. Cambridge University Press. pp. 53–. ISBN 978-0-521-53854-1.

- Jacob Bercovitch; Victor Kremenyuk; I William Zartman (3 December 2008). "Characteristics of ethno-religious conflicts". The SAGE Handbook of Conflict Resolution. SAGE Publications. pp. 265–. ISBN 978-1-4462-0659-1.

- John Coffey (2000), p. 26

- Benjamin j. Kaplan (2007), Divided by Faith, Religious Conflict and the Practice of Toleration in Early Modern Europe, p. 3

- Coffey 2000: 85.

- Coffey 2000: 86.

- Coffey 2000: 81.

- Coffey 2000: 92.

- Onfray, Michel (2007). Atheist manifesto: the case against Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. Leggatt, Jeremy (translator). Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55970-820-3.

- Flannery, Edward H. The Anguish of the Jews: Twenty-Three Centuries of Antisemitism. Paulist Press, first published in 1985; this edition 2004, pp. 11–2. ISBN 0-8091-2702-4. Edward Flannery

- Hinnells, John R. (1996). Zoroastrians in Britain: the Ratanbai Katrak lectures, University of Oxford 1985 (Illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 303. ISBN 9780198261933.

- Coffey 2000: 14.

- Coffey 2000, 2

- John Coffey (2000), p. 12

- John Coffey (2000), p. 33

- The Works of Richard Hooker, II, p. 485; quoted after: John Coffey (2000), p. 33

- quoted after Coffey (2000), 27

- Coffey 2000: 58.

- Coffey 2000: 57.

- John Locke (1698): A Letter Concerning Toleration; Online edition

- А.С.Пругавин, ук. соч., с.27-29

- Ал. Амосов, "Судный день", в списание "Церковь" № 2, 1992, издателство "Церковь", Москва, с.11

- "Like the extremist Islamic clerics who today provide inspiration for terrorist campaigns, the [Catholic] priests could not be treated like men who only sought the spiritual nourishment of the flock." Coffey 2000: 38&39.

- US Congress, House committee on foreign affairs (1994). Religious Persecution: Hearings Before the Subcommittee on International security, International organizations and Human Rights. U.S. Government printing office. ISBN 0-16-044525-6.

- "How Religious Restrictions Have Risen Around the World". July 15, 2019.

- "Quotes from experts on the future of democracy". February 21, 2020.

- Society for Human rights|official website

- Mack, Michelle L. (February 2014). "Religious Human Rights and the International Human Rights Community: Finding Common Ground - Without Compromise". Notre Dame Journal of Ethics, Law & Public Policy. 13 (2). Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Cotler, Irwin. “JEWISH NGOs, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND PUBLIC ADVOCACY: A COMPARATIVE INQUIRY.” Jewish Political Studies Review, vol. 11, no. 3/4, 1999, pp. 61–95. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25834458. Accessed 27 May 2020.

- Durham Jr., W. Cole (1996). "Perspectives on Religious Liberty: a comparative framework". In Van der Vyver, Johan David; Witte Jr., John (eds.). Religious Human Rights in Global Perspective: Legal Perspectives. 2. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 90-411-0177-2.

- Laursen, John Christian; Nederman, Cary J. (1997). Beyond the Persecuting Society: Religious Toleration Before the Enlightenment. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-8122-1567-0.

- "Atheists face death in 13 countries, global discrimination: study". reuters.com.

- "'God Does Not Exist' Comment Ends Badly for Indonesia Man". Retrieved 2012-01-20.

- Protest for Religious Rights in the USSR: Characteristics and Consequences, David Kowalewski, Russian Review, Vol. 39, No. 4 (Oct., 1980), pp. 426–441, Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Editors and Board of Trustees of the Russian Review

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Anticlericalism (2007 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.)

- Greeley, Andrew M. 2003. Religion in Europe at the end of the second millennium: a sociological profile. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers.

- Pospielovsky, Dimitry. 1935. The Orthodox Church in the History of Russia Published 1998. St Vladimir's Seminary Press, page 257, ISBN 0-88141-179-5.

- Miner, Steven Merritt. 2003. Stalin's holy war religion, nationalism, and alliance politics, 1941–1945. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. page 70.

- Davies, Norman. 1996. Europe: a history. Oxford: Oxford University Press. page 962.

- Pipes (1989):55.

- Elsie, Robert. 2000. A Dictionary of Albanian Religion, Mythology, and Folk Culture. C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-85065-570-1. page 18.

- "Seleucidæ". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- Shimron, Yonat (November 12, 2019). "FBI report: Jews the target of overwhelming number of religious-based hate crimes". Religion News Service. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- Buhl, F.; Welch, A.T. (1993). "Muḥammad". Encyclopaedia of Islam. 7 (2nd ed.). Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 360–376. ISBN 9004094199.

- An Introduction to the Quran (1895), p. 185

- "July 15, 2019 A Closer Look at How Religious Restrictions Have Risen Around the World". Religion and Public Life. PEW Research Center. July 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "2019 Report on International Religious Freedom: Central African Republic". OFFICE OF INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Report. U.S. Department of State.

- "2019 Report on International Religious Freedom: Nigeria". OFFICE OF INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Report. U.S. State Department.

- "2019 Report on International Religious Freedom: China (Includes Tibet, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Macau)". OFFICE OF INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Report. U.S. Department of State.

- "2019 Report on International Religious Freedom: Indonesia". OFFICE OF INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Report. U.S. Department of State.

- "2019 Report on International Religious Freedom: Saudi Arabia". OFFICE OF INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Report. U.S. Department of State.