Hakon Jarl runestones

The Hakon Jarl Runestones are Swedish runestones from the time of Canute the Great.

Two of the runestones, one in Uppland (U 617) and one in Småland (Sm 76) mention a Hakon Jarl,[1] and both runologists and historians have debated whether they are one and the same, or two different men.[2] Moreover, all known Hakon Jarls have been involved in the debate: Hákon Sigurðarson (d. 995), his grandson Hákon Eiríksson (d. 1029), Hákon Ívarsson (d. 1062) and Hákon Pálsson (d. 1122).[3] The most common view among runologists (Brate, von Friesen, Wessén, Jansson, Kinander and Ruprecht) is that the two stones refer to different Hakon Jarls and that one of them was Swedish and the other one Norwegian.[3]

U 16

This runestone was located in Nibble on the island of Ekerö, but it has disappeared. In scholarly literature it was first described by Johannes Bureus (1568–1652), and it was depicted by Leitz in 1678. Johan Hadorph noted in 1680 that the name of the deceased in the inscription had been bitten off by locals who believed that doing so would help against tooth ache. Elias Wessén notes that roði Hakonaʀ refers to a leidang organization under a man named Hákon who could have been a jarl, but he considers it most likely that Hákon refers to the Swedish king Hákon the Red.[4] Others identify Hákon with the Norwegian jarl Hákon Eiríksson, like Sm 76, below,[3] and Omeljan Pritsak considers the man to whom the stone was dedicated to have been a member of the army of jarl Hákon Eiríksson in England.[5]

Latin transliteration:

- [kuni * auk : kari : raisþu * stin * efiʀ ...r : han : uas : buta : bastr : i ruþi : hakunar]

Old Norse transcription:

- Gunni ok Kari ræisþu stæin æftiʀ ... Hann vas bonda bæstr i roði Hakonaʀ.

English translation:

- "Gunni and Kári raised the stone in memory of ... He was the best husbandman in Hákon's dominion."[6]

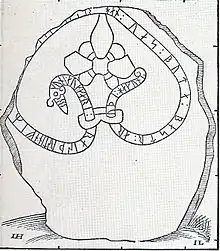

U 617

This runestone is also called the Bro Runestone after the church by which it is located. It is raised by the same aristocratic family as the Ramsund carving and the Kjula Runestone, which allows scholars to study the family of the Hakon Jarl who is mentioned on this runestone.[3] He is considered to have been Swedish and his son Özurr may have been responsible for organizing the local defense organization against raiders on the shores of lake Mälaren.[3] However, the only recorded organization of such a defence is from England and consequently both this Hakon Jarl and his son Özurr may have been active in England in the Þingalið instead.[5] Omeljan Pritsak argues that this Hakon is the same as the one who is mentioned on the Södra Betby Runestone and whose son Ulf was in the west, i.e. in England.[7] This Swedish Hakon Jarl would then actually be the Norwegian Hákon Eiríksson.[7]

Like the Norwegian jarl Hákon Eiríksson, this Swedish Hakon Jarl has been identified with the Varangian chieftain Yakun who is mentioned in the Primary Chronicle.[3]

The reference to bridge-building in the runic text is fairly common in rune stones during this time period. Some are Christian references related to passing the bridge into the afterlife. At this time, the Catholic Church sponsored the building of roads and bridges through the use of indulgences in return for intercession for the soul.[8] There are many examples of these bridge stones dated from the eleventh century, including runic inscriptions Sö 101 and U 489.[8]

Latin transliteration:

- kinluk × hulmkis × tutiʀ × systiʀ × sukruþaʀ × auk × þaiʀa × kaus × aun × lit × keara × bru × þesi × auk × raisa × stain × þina × eftiʀ × asur × bunta * sin × sun × hakunaʀ × iarls × saʀ × uaʀ × uikika × uaurþr × miþ × kaeti × kuþ × ialbi × ans × nu × aut × uk × salu

Old Norse transcription:

- Ginnlaug, Holmgæiʀs dottiʀ, systiʀ Sygrøðaʀ ok þæiʀa Gauts, hon let gæra bro þessa ok ræisa stæin þenna æftiʀ Assur, bonda sinn, son Hakonaʀ iarls. Saʀ vaʀ vikinga vorðr með Gæiti(?). Guð hialpi hans nu and ok salu.

English translation:

- "Ginnlaug, Holmgeirr's daughter, Sigrøðr and Gautr's sister, she had this bridge made and this stone raised in memory of Ôzurr, her husbandman, earl Hákon's son. He was the viking watch with Geitir(?). May God now help his spirit and soul."[9]

Sm 76

Only a fragment remains of this runestone, but before it was destroyed, the text had been read by runologists. The fragment is located in the garden of the inn of Komstad in Småland. It was originally raised by a lady in memory of Vrái who had been the marshall of an earl Hakon, who was probably the earl Håkon Eiriksson.[10][11] Some time earlier, Vrái had raised the Sävsjö Runestone in memory of his brother Gunni who died in England.[5]

The generally accepted identification with Hákon Eiríksson was made by von Friesen in 1922, and he is also held to appear on U 16, above.[3]

Latin transliteration:

- [tufa : risti : stin : þina : eftiʀ : ura : faþur : sin : stalar]a : hkunaʀ : [iarls]

Old Norse transcription:

- Tofa ræisti stæin þenna æftiʀ Vraa, faður sinn, stallara Hakonaʀ iarls.

English translation:

- "Tófa raised this stone in memory of Vrái, his father, Earl Hákon's marshal."[12]

Notes

- Pritsak 1981:406

- Pritsak 1981:406ff.

- Pritsak 1981:407.

- Wessén 1940-43:24-26.

- Pritsak 1981:411.

- Entry U 16 in Rundata 2.0 for Windows.

- Pritsak 1981:412.

- Gräslund 2003:490-492.

- Entry U 617 in Rundata 2.0 for Windows.

- Jansson 1980:38.

- Pritsak 1981:343

- Entry Sm 76 in Rundata 2.0 for Windows.

Sources and external links

- A Swedish site with a picture of the Bro Runestone.

- Brate, E. (1922). Sveriges runinskrifter. pp. 122-124.

- Gräslund, Anne-Sofie (2003). "The Role of Scandinavian Women in Christianisation: The Neglected Evidence". In Carver, Martin (ed.). The Cross Goes North: Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe, AD 300-1300. Boydell Press. pp. 483–496. ISBN 1-903153-11-5.

- Jansson, Sven B. (1980). Runstenar. STF, Stockholm. ISBN 91-7156-015-7

- Pritsak, Omeljan. (1981). The origin of Rus'. Cambridge, Mass.: Distributed by Harvard University Press for the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. ISBN 0-674-64465-4

- Rundata

- Wessén, E.; Jansson, S. B. F. (1940–1943). Sveriges runinskrifter: VI. Upplands runinskrifter del 1. Stockholm: Kungl. Vitterhets Historie och Antikvitets Akademien. ISSN 0562-8016.