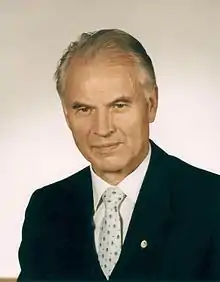

Hans Modrow

Hans Modrow (German pronunciation: [ˈhans ˈmoːdʁo]; born 27 January 1928)[1] is a German politician best known as the last communist premier of East Germany. Taking office in the middle of the Peaceful Revolution, he was the de facto leader of the country for much of the winter of 1989 and 1990, attempting to delay German reunification.

Hans Modrow | |

|---|---|

Modrow on 17 November 1989 | |

| Chairman of the Council of Ministers | |

| In office 13 November 1989 – 12 April 1990 | |

| President | Egon Krenz Manfred Gerlach Sabine Bergmann-Pohl (acting) |

| Deputy | Lothar de Maizière Christa Luft Peter Moreth |

| Preceded by | Willi Stoph |

| Succeeded by | Lothar de Maizière |

| Member of the European Parliament | |

| In office 20 July 1999 – 19 July 2004 | |

| Member of the Bundestag | |

| In office 3 October 1990 – 1994 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 27 January 1928 Jasenitz, Province of Pomerania, Free State of Prussia, Weimar Republic (now Jasienica, Poland) |

| Political party | Socialist Unity Party of Germany (1949–1989) Party of Democratic Socialism (1989–2007) The Left (2007–present) |

| Spouse(s) | Annemarie Straubing (d. 2003) |

| Children | 2 daughters |

| Profession | Politician |

After the end of Communist rule and reunification of Germany, he was singled out by the new government and convicted of electoral fraud and perjury by the Dresden District Court in 1995, on the basis that he had been the SED official nominally in charge of the electoral process. He was the honorary chairman of the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS)[2] and has been the president of the "council of elders" of the Left Party since 2007.[3]

Early life and education

Modrow was born in Jasenitz, Province of Pomerania, Germany, now Jasienica part of the town of Police in Poland.[4] He attended a Volksschule, trained as a machinist from 1942 to 1945 when he was filled with intense hatred of the Bolsheviks, whom he deemed as subhumans, inferior to Germans physically and morally.[5] He later served briefly in the Volkssturm in 1945.[4] and was subsequently held as a prisoner of war by the Soviet Red Army in May 1945. He and other German prisoners were sent to a farm to work. Upon arrival, his backpack was stolen, making him begin to rethink the Germans' so called camaraderie. Days later, he was appointed as a driver to a Soviet captain, who asked him about Heinrich Heine, a German poet. Modrow never heard of him and felt embarrassed that the people he thought of as "subhumans" knew more about German culture than he. Transported to a POW camp near Moscow, he joined an anti-fascist school for Wehrmacht members and received training in Marxism-Leninism, which he embraced.[5][4] Upon release in 1949 he worked as a machinist for LEW Hennigsdorf.[4] That same year he joined the Socialist Unity Party (SED).[4]

From 1949 to 1961, Modrow worked in various functions for the Free German Youth (FDJ) in Brandenburg, Mecklenburg and Berlin and in 1952/1953 studied at the Komsomol college in Moscow.[4] From 1953 to 1961, he served as an FDJ functionary in Berlin.[4] From 1954 to 1957, he studied at the SED's Karl Marx school in Berlin, graduating as a social scientist.[4] In 1959–1961 he studied at the University of Economics in Berlin-Karlshorst and obtained the degree of graduate economist.[4] He gained his doctorate at the Humboldt University of Berlin in 1966.[4] West Germany's Federal Intelligence Service (BND) kept Modrow under observation from 1958 to 2013.[6][7]

Communist party career

Modrow had a long political career in East Germany, serving as a member of the Volkskammer from 1957 to 1990 and in the SED's Central Committee (ZK) from 1967 to 1989, having previously been a candidate for the ZK from 1958 to 1967.[4] From 1961 to 1967 he was first secretary of the district administration of the SED in Berlin-Köpenick and secretary for agitation and propaganda from 1967 to 1971 in the SED's district leadership in Berlin.[4] From 1971 to 1973 he worked as the head of the SED's department of agitation.[4] In 1975 he was awarded the GDR's Patriotic Order of Merit in gold[8] and received the award of the Order of Karl Marx in 1978.[9]

From 1973 onward, he was the SED's first secretary in Dresden, East Germany's third-largest city.[4] He was prevented from rising any further than a local party boss, largely because he was one of the few SED leaders who dared to publicly criticise longtime SED chief Erich Honecker. He developed some important contacts with the Soviet Union, including eventual Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. In early 1987, Gorbachev and the KGB explored the possibility of installing Modrow as Honecker's successor.[10] From 1988 to 1989, the Stasi, under the orders of Honecker and Erich Mielke, conducted a massive surveillance operation against Modrow with the intention of gathering enough evidence to convict him of high treason.[11]

Peaceful Revolution

During the Peaceful Revolution of 1989, Modrow ordered thousands of Volkspolizei, Stasi, Combat Groups of the Working Class and National People's Army troops to crush a demonstration at the Dresden Hauptbahnhof on 4–5 October. Some 1,300 people were arrested. In a top secret and encrypted telex to Honecker on 9 October, Modrow reported: "With the determined commitment of the comrades of the security organs, anti-state terrorist riots were suppressed".[12]

When Honecker was toppled on 18 October, Gorbachev hoped that Modrow would become the new leader of the SED. Egon Krenz, however, was selected instead.[13] He became premier following the resignation of Willi Stoph on 13 November. After Krenz's resignation as leader of the SED on 3 December, Modrow became the de facto leader of East Germany; the premiership was the highest state post in East Germany. The SED, which later changed its name to the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS), had abandoned its monopoly of power two days earlier.

To defeat the opposition's demand for the complete dissolution of the Stasi, it was renamed as the "Office for National Security" (Amt für Nationale Sicherheit – AfNS) on 17 November 1989. Modrow's attempt to re-brand it further as the "Office for the Protection of the Constitution of the GDR" (Verfassungsschutz der DDR) failed due to pressure from the public and the opposition parties and the AfNS was dissolved on 13 January 1990.[14] The Modrow government gave orders to destroy incriminating Stasi files.[12]

On 7 December 1989, Modrow accepted the proposal of the East German Round Table opposition groups to hold free elections within six months. He mostly ignored the rest of the Round Table's recommendations and attempted to rule through the Volkskammer. He regarded talks with the democratic socialist Round Table opposition parties as a means of delaying and preferably blocking political change in the GDR. To halt the outflow of citizens and the disintegration of society, Modrow and the Round table agreed on 28 January to bring the scheduled elections forward to 18 March.

Some of the Round Table parties strove for a "third way" model of democratic socialism and therefore agreed with Modrow to slow down or block a reunification with capitalist West Germany. As the SED-PDS regime grew weaker, Modrow on 1 February 1990 proposed a slow, three-stage process that would create a neutral German confederation and continued to oppose "rapid" reunification. The collapse of the East German state and economy in early 1990 and the approaching East German free elections allowed Helmut Kohl's government in Bonn to disregard Modrow's demand for neutrality.[15] From 5 February 1990 on, Modrow included eight representatives of opposition parties and civil liberties groups as ministers without portfolio in his cabinet. On 13 February 1990, Modrow met with West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, asking for an accommodation loan of 15 billion DM, which was rejected by Kohl.[16]

Modrow remained premier until the 1990 East German general election on 18 March 1990.[4]

Criminal sentence

On 27 May 1993 the Dresden District Court found Modrow guilty of electoral fraud committed in the Dresden municipal elections in May 1989, specifically, understating the percentage of voters who refused to vote for the official slate.[17] (East Germany had dominant-party system until March 1990.) Modrow did not deny the charges, but argued that the trial was politically motivated and that the court lacked jurisdiction for crimes committed in East Germany.[17] The judge declined to impose a prison sentence or a fine.[17] The Dresden District Court revoked the decision in August 1995, however, and Modrow was sentenced to nine months on probation.[18][19]

Later life

After German reunification, Modrow served as a member of the Bundestag (1990–1994)[4] and of the European Parliament (1999–2004).[20] Since leaving office, Modrow has authored a number of books on his political experiences, his continued Marxist political views and his disappointment at the dissolution of the Eastern Bloc.[21][22] In 2006, Modrow blamed West Germany for the East Germans killed by the communist regime at the Berlin Wall. He also called East Germany an "effective democracy".[23] He has been criticized for maintaining contacts with Neo-Stalinist groups.[24]

Citations

- Profile of Hans Modrow

- "West German Secret Service Opens GDR Files". Der Spiegel. 16 October 2009. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- "Modrow: "Die Gefahr von Krieg war nach 1945 noch nie so hoch wie jetzt"". Märkische Allgemeine. 22 February 2019.

- "Findbücher / 04 Bestand: Dr. Hans Modrow, MdB (1990 bis 1994)" (PDF) (in German). Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. June 2001. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- Applebaum, Anne (2012). Iron Curtain: The Crushing of Eastern Europe 1944-1956. New York USA: Doubleday. p. 17-18. ISBN 9780385515696.

- BND spionierte mindestens 71.500 DDR-Bürger aus

- David Martin (28 February 2018). "Last East German leader Hans Modrow demands access to West's intelligence files". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Vaterländischer Verdienstorden in Gold". Neues Deutschland (in German). 1 October 1975. p. 5.

- "Karl-Marx-Orden an Hans Modrow verliehen". Neues Deutschland (in German). 28 January 1978. p. 2.

- "Did KGB plot a coup against the East German leader in 1987?". Bild. 30 October 2009. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Andreas Debski (5 June 2018). "Honecker wollte Modrow ins Gefängnis sperren lassen". Leipziger Volkszeitung (in German). Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- Gerhard Besier (25 November 1996). "SED/PDS Vom ehrlichen Hans". Focus (in German). Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Sebetsyen, Victor (2009). Revolution 1989: The Fall of the Soviet Empire. New York City: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-375-42532-5.

- Friedheim 1995, p. 168.

- Friedheim 1995, pp. 167–171.

- Holger Schmale (12 February 2015). "Treffen von Hans Modrow und Helmut Kohl 1990: Die Delegation aus Ost-Berlin fühlte sich gedemütigt". Berliner Zeitung.

- Kinzer, Stephen (1993-05-28). "Ex-East German Leader Convicted Of Vote Fraud but Not Punished". New York Times. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- (in German) Urteil: Bewährungsstrafe für Hans Modrow Mitteldeutsche Zeitung. 10 May 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- (in German) Modrow, Hans Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- "Hans Modrow". European Parliament MEPs. European Parliament. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- "Perestroika and Germany: the truth behind the myths". Amazon. Artery Publications with Marx Memorial Library. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- "Aufbruch und Ende". Amazon. Edition Berolina. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- Dirk von Nayhauss: „Ich war kein Held“ Interview mit Hans Modrow. in: Cicero, May 2006, accessed 9 February 2020

- Stefan Berg (3 May 2009). "Vergangenheitsbewältigung: Modrows Kontakte zu Neostalinisten belasten die Linke". Spiegel Online (in German). Retrieved 16 February 2019.

References

- Friedheim, Daniel V. (1995). "Accelerating collapse: The East German road from liberalization to power-sharing and its legacy". In Shain, Yossi; Linz, Juan J. (eds.). Between States: Interim Governments and Democratic Transitions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-47417-5.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Willi Stoph |

Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the German Democratic Republic 1989–1990 |

Succeeded by Lothar de Maizière |