Free State of Prussia

The Free State of Prussia (German: Freistaat Preußen) was a state of Germany from 1918 to 1947.

| Free State of Prussia Freistaat Preußen | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State of Germany | |||||||||||||

| 1918–1935/1947 | |||||||||||||

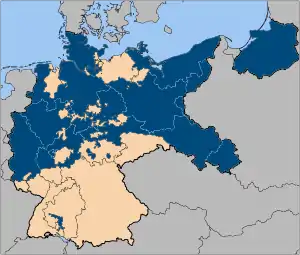

The Free State of Prussia in 1925 | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Berlin | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

• 1925[1] | 292,695.36 km2 (113,010.31 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||

• 1925[1] | 38,175,986 | ||||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||||

| • Type | Republic | ||||||||||||

| • Motto | Gott mit uns "God with us" | ||||||||||||

| Reichsstatthalter | |||||||||||||

• 1933–1935 | Adolf Hitler | ||||||||||||

• 1935–1945 | Hermann Göring | ||||||||||||

| Minister-President | |||||||||||||

• 1918 (first) | Friedrich Ebert | ||||||||||||

• 1933-1945 (last) | Hermann Göring | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | State Diet | ||||||||||||

• Upper Chamber | State Council | ||||||||||||

• Lower Chamber | House of Representatives | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar/World War II | ||||||||||||

| 9 November 1918 | |||||||||||||

| 30 November 1920 | |||||||||||||

| 20 July 1932 | |||||||||||||

| 30 January 1933 | |||||||||||||

| 30 January 1935 | |||||||||||||

| 25 February 1947 | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

History of Brandenburg and Prussia | ||||

| Northern March 965–983 |

Old Prussians pre-13th century | |||

| Lutician federation 983 – 12th century | ||||

| Margraviate of Brandenburg 1157–1618 (1806) (HRE) (Bohemia 1373–1415) |

Teutonic Order 1224–1525 (Polish fief 1466–1525) | |||

| Duchy of Prussia 1525–1618 (1701) (Polish fief 1525–1657) |

Royal (Polish) Prussia (Poland) 1454/1466 – 1772 | |||

| Brandenburg-Prussia 1618–1701 | ||||

| Kingdom in Prussia 1701–1772 | ||||

| Kingdom of Prussia 1772–1918 | ||||

| Free State of Prussia (Germany) 1918–1947 |

Klaipėda Region (Lithuania) 1920–1939 / 1945–present |

Recovered Territories (Poland) 1918/1945–present | ||

| Brandenburg (Germany) 1947–1952 / 1990–present |

Kaliningrad Oblast (Russia) 1945–present | |||

The Free State of Prussia was established in 1918 following the German Revolution, abolishing the German Empire and founding the Weimar Republic in the aftermath of the First World War. The new state was a direct successor to the Kingdom of Prussia, but featured a democratic, republican government and smaller area based on territorial changes after the war. Despite bearing the brunt of Germany's territorial losses in Europe, Prussia remained the dominant state of Germany, comprising almost 5⁄8 (62.5%) of the country's territory and population, and home to the federal capital, Berlin.[1] Prussia changed from the authoritarian state it had been under previous rulers to a democratic bastion within the Weimar Republic where, unlike in other states, democratic parties always ruled in majority.

The Free State of Prussia's democratic government was overthrown in the Preußenschlag in 1932, placing the state under direct rule in a coup d'état led by Chancellor Franz von Papen and forcing Minister-President Otto Braun from office. The establishment of Nazi Germany in 1933 began the Gleichschaltung process, ending legal challenges to the Preußenschlag and placing Prussia under the direct rule of the National Socialist German Workers' Party, with Hermann Göring as Minister-President. In 1934, all German states were de facto replaced by the Gaue system and converted to rudimentary bodies, effectively ending Prussia as a single territorial unit of Germany. After the end of World War II in 1945, Otto Braun approached Allied officials in occupied Germany to reinstate the legal Prussian government, but was rejected and Prussia was abolished in 1947.

History of Prussia after 1918

1918: Aftermath of World War I

Except for its overseas colonies, Alsace-Lorraine and the Bavarian portion of the Saargebiet, all German territorial losses as a result of World War I were Prussian losses. As specified in the Treaty of Versailles, the former kingdom lost territory to Belgium (Eupen and Malmedy), Denmark (North Schleswig), Lithuania (Memel Territory) and Czechoslovakia (the Hultschin area). The Saargebiet was administered by the League of Nations until 1935. The Rhine Province became a demilitarised zone, although it remained under Prussian civil administration.

The bulk of Prussia's losses were to Poland, including most of the provinces of Posen and West Prussia, and an eastern section of Silesia. Danzig was placed under the administration of the League of Nations as the Free City of Danzig. These losses separated East Prussia from the rest of the country, now only accessible by rail through the Polish corridor or by sea.

Since the Germans had not been invited to the peace conference taking place in Versailles and because the Allies had deliberately kept the terms of the treaty from being made public prior to presenting them to the German delegation, many Germans feared that the Allies were preparing to demand even harsher peace terms. In particular, it was thought that the French would seek to annex the Rhineland. Some prominent politicians, particularly Rhenish politicians such as Mayor of Cologne and future German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, called for Prussia to be divided into smaller and more manageable states. However, both the Reich and Prussian governments in Berlin were dominated by traditionalist sentiment and strongly opposed the dissolution of Prussia.

Essentially, apart from its territorial losses and having its government placed on a democratic footing, Prussia continued unchanged. It remained by far the largest state of the Reich, with more territory and people than the other states combined.

1918–1932: Democratic bastion

During the 500 years of Hohenzollern rule, Prussia (and its predecessor, Brandenburg) had been synonymous with authoritarianism. In contrast, Prussia was a bulwark of democracy during the Weimar Republic. The restrictive Prussian three-class franchise was abolished shortly after Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated. Power now passed from the Junker landowners and great industrialists to "Red Berlin" and the industrialised Ruhr Area – both with working-class majorities. Prussia now became a stronghold of the left.

From 1918 to 1932, Prussia was governed by a coalition of the Social Democrats, Catholic Centre, and German Democrats–the member parties of the Weimar Coalition. For all but nine months of that period (April–November 1921 and February–April 1925), a Social Democrat was minister-president. From 1921 to 1925, coalition governments included the German People's Party. Unlike in other states of the German Reich, majority rule by democratic parties in Prussia was never endangered. Nevertheless, in East Prussia and some industrial areas, the National Socialist German Workers Party (or Nazi Party) of Adolf Hitler gained more and more influence and popular support, especially from the lower middle class.

Otto Braun, a Social Democrat from East Prussia, served as Prussian minister-president almost continuously from 1920 to 1932. A capable leader, he implemented several trend-setting reforms together with his minister of the interior, Carl Severing, which were also models for the later Federal Republic of Germany (FRG). For instance, a Prussian minister-president could be forced out of office only if there was a "positive majority" for a potential successor. This concept, known as the constructive vote of no confidence, was carried over into the Basic Law of the FRG. Largely because of this provision, the centre-left coalition was able to stay in office because neither the far left nor the far right could possibly command enough support in the legislature to form a government.

1932: Prussian coup

All of this changed on 20 July 1932 with the Preußenschlag ("Prussian coup"): Reich Chancellor Franz von Papen got President Hindenburg to remove the elected Prussian state government under Otto Braun on the pretext that it had lost control of public order. This was triggered by Altona Bloody Sunday, a shootout between the SA and Communists (Altona was still a part of Prussia at that time). After this emergency decree, Papen appointed himself Reich Commissioner for Prussia and took control of the government. This made it easy for Adolf Hitler to assume control over Prussia in the following year.

Otto Braun's government filed suit in the courts, but the cases remained unresolved due to the war and the subsequent Allied occupation and partition of Germany.

Establishment of Nazi rule in Prussia

On 30 January 1933, Hitler had been appointed chancellor of Germany. As part of the deal, Papen was formally appointed minister-president of Prussia in addition to his role as Vice Chancellor of the Reich. In a little-noticed appointment, Hitler's top lieutenant Hermann Göring became the state's interior minister.

Four weeks later (27 February 1933), the Reichstag was set on fire. At Hitler's urging, President Paul von Hindenburg issued the Reichstag Fire Decree, which suspended civil liberties in Germany. Six days after the fire, the Reichstag election of 5 March 1933 strengthened the position of the Nazi Party, although they did not achieve an absolute majority. However, with their coalition partners, the German National People's Party, Hitler now commanded a bare majority in the Reichstag. Göring figured prominently in this election, as he was commander of the largest police force in the Reich. His police beat and harassed the other parties (especially the Communists and Social Democrats), and only allowed the Nazis and Nationalists to campaign relatively unmolested.

The new Reichstag was opened in the Garrison Church of Potsdam on 21 March 1933 in the presence of President Paul von Hindenburg, who had long since descended into senility. In a propaganda-filled meeting between Hitler and the NSDAP, the "marriage of old Prussia with young Germany" was celebrated, to win over the Prussian monarchists, conservatives, and nationalists and induce them to vote for the Enabling Act. The act was passed on 23 March 1933, legally granting Hitler dictatorial powers.

In April 1933, Papen was visiting the Vatican. The Nazis took advantage of his absence and appointed Göring in his place. With this act, Hitler was able to take power decisively in Germany, since he now had the whole apparatus of the Prussian government, including the police, at his disposal. By 1934 almost all Prussian ministries had been merged with the corresponding Reich ministries.

Dismantlement of Prussia

In the centralized state created by the Nazis in the "Law on the Reconstruction of the Reich" ("Gesetz über den Neuaufbau des Reiches", 30 January 1934) and the "Law on Reich Governors" ("Reichsstatthaltergesetz", 30 January 1935) the States and Provinces of Prussia were dissolved, in fact if not in law. The federal state governments were now controlled by governors for the Reich who were appointed by the Chancellor. Parallel to that, the organization of the party into districts (Gau) gained increasing importance, as official in charge of a Gau (the infamous Gauleiter) was again appointed by the Chancellor who was at the same time chief of the NSDAP. Hitler appointed himself formally as Governor of Prussia, although his functions were exercised by Göring.

Two years later, Hitler (who by then was head of state and the absolute dictator of Germany) formally transferred the office of Prussian Reichsstatthalter from himself to Göring. This position, as well as that of Minister-President (which Göring had already held from 1933) continued to exist until the dying days of the Third Reich when Hitler dismissed Göring from all state and Reich offices for alleged treason.

Some changes were still made to Prussian provinces after this time. For example, the Greater Hamburg Act of 1937 transferred some territory from the provinces of Hanover and Schleswig-Holstein to Hamburg while at the same time annexing Hamburgian Geesthacht and the Hanseatic City of Lübeck to Schleswig-Holstein as well as Hamburgian Cuxhaven to the Province of Hanover. Other redeployments took place in 1939, involving cessions of Prusso-Hanoveran suburban municipalities to Bremen and in return the annexation of Bremian Bremerhaven to the Province of Hanover. Also Hanoveran Wilhelmshaven was ceded to Oldenburg. In 1942 redeployments involved the provinces of Saxony and Hanover and the Brunswick.

The Prussian lands transferred to Poland after the Treaty of Versailles were reannexed during World War II. However, most of this territory was not reintegrated back into Prussia but assigned to separate Gaue of Nazi Germany.

Shortly before his death, Hitler dismissed Göring from all Reich offices for alleged treason. The Nazi dictator's last will and testament, drafted shortly before his suicide, harshly condemned the Prussian minister-president but did not appoint a successor for any Prussian offices held by Göring or make any other mention of their status. Likewise, the short-lived Flensburg government under Karl Dönitz made no effort to fill any Prussian state offices. In reality, these had long been relegated to little more than titular positions compared to Göring's more prominent roles in the Nazi regime.

Formal dissolution

With the end of National Socialist rule in 1945 came the division of Germany into Zones of Occupation, and the transfer of control of everything east of the Oder-Neisse line to other countries. As was the case after World War I, almost all of this territory had been Prussian territory (a small portion of the land east of the revised border had belonged to Saxony). Most of the land went to Poland and the northern third of East Prussia, including Königsberg, now Kaliningrad was annexed by the Soviet Union. The losses represented nearly two-fifths of Prussian territory and nearly a quarter of territory within Germany's pre-1938 borders. An estimated ten million Germans fled or were forcibly expelled from these territories as part of the German exodus from Eastern Europe.

What remained of Prussia comprised both a little over half of the remaining German territory and a little over half of Prussia's pre-1914 territory. In Law No. 46 of 25 February 1947, the Allied Control Council proclaimed the dissolution of the Prussian state.[2] The Allies cited Prussia's history of militarism as a reason for dissolving it. In reality, Prussia had ceased to exercise administrative functions in 1933 and these had now been absorbed into the administration of the occupying powers in their respective geographic areas of control and its reconstitution was also opposed (if not for the same reasons) by powerful German postwar politicians, especially the first West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer.

Even without all of this to consider, postwar tensions between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union eventually resulted in the Soviets establishing a separate sovereign state in what essentially had become eastern Germany, the German Democratic Republic. This development effectively cut off Prussia's western territories from what had been its power base in Brandenburg, thus making the establishment of a credible successor state to the Free State of Prussia all but impossible.

Government

Unlike its authoritarian pre-war predecessor, Prussia was a promising democracy within Germany. The abolition of the aristocracy transformed Prussia into a region strongly dominated by the left wing of the political spectrum, with "Red Berlin" and the industrial centre of the Ruhr Area exerting a major influence. During this period, a coalition of centre-left parties ruled, predominantly under the leadership of East Prussian Social Democrat Otto Braun. While in office he implemented several reforms together with his Minister of the Interior, Carl Severing, which were also models for the later Federal Republic of Germany. For instance, a Prussian prime minister could only be forced out of office if there was a "positive majority" for a potential successor. This concept, known as the constructive vote of no confidence, was carried over into the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany. Most historians regard the Prussian government during this time as far more successful than that of Germany as a whole.

Similar to other German states both now and at the time, executive power was continued to be vested in a Minister-President of Prussia and laws established by a Landtag elected by the people.

Ministers-President of the Free State of Prussia

| # | Name | Took office | Left office | Party |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Friedrich Ebert | 9 November 1918 | 11 November 1918 | SPD |

| 2 | Paul Hirsch | 11 November 1918 | 27 March 1920 | SPD |

| 3 | Otto Braun | 27 March 1920 | 21 April 1921 | SPD |

| 4 | Adam Stegerwald | 21 April 1921 | 5 November 1921 | Centre |

| – | Otto Braun | 5 November 1921 | 18 February 1925 | SPD |

| 5 | Wilhelm Marx | 18 February 1925 | 6 April 1925 | Centre |

| – | Otto Braun | 6 April 1925 | 20 July 1932a | SPD |

| Position administered by the Reichskommissar between 20 July 1932 and 30 January 1933 | ||||

| 6 | Franz von Papen | 30 January 1933 | 10 April 1933 | Independent |

| 7 | Hermann Göring | 10 April 1933 | 24 April 1945 | NSDAP |

| a. Ousted during the Preußenschlag; formally deposed on 30 January 1933. | ||||

Subdivisions of Prussia

Effects of World War I

- East

- The Memel Region of East Prussia was ceded to Lithuania. The remainder of province of Silesia that was not ceded to Poland and Czechoslovakia was split into the provinces of Upper Silesia and Lower Silesia in 1919 – although they were temporarily recombined (1938–1941).

- North

- In the province of Schleswig-Holstein, Allied powers organised two plebiscites in Northern and Central Schleswig on 10 February and 14 March 1920, respectively. In Northern Schleswig 75% voted for reunification with Denmark and 25% for staying with Germany, this new addition to Denmark formed the counties of Aabenraa, Haderslev, Sønderborg, and Tønder, from 1970 to 2007 this ceded areas were merged in South Jutland County. In Central Schleswig the situation was reversed with 80% voting for Germany and 20% for Denmark. No vote ever took place in the southern third of Schleswig.

- West

- The southern tip of the Rhine Province was placed under French administration as the Saar by the League of Nations. The Eupen and Malmedy regions in the west of the Rhine Province were ceded to Belgium, forming the region that contains the German-speaking community of Belgium.

Changes prior to the Nazi regime

In 1920, the Greater Berlin Act was passed to create Greater Berlin, enlarging the Prussian capital at the expense of Brandenburg, from which Berlin had been separated in 1881.[3] The Greater Berlin Act effectively enlarged the size of the city 13-fold, and its borders are largely maintained by the modern German state of Berlin.

The remainder of the provinces of Posen and West Prussia were combined to form Posen-West Prussia in 1922.

Following a plebiscite in 1929 Waldeck merged with Prussia. The event was commemorated by a 3 Reichsmark coin.[4]

Post-war dismemberment

After the Allied occupation of Germany in 1945, the provinces of Prussia were split up into the following territories/German states:

- Ceded to the Soviet Union

- The northern third of East Prussia. Today, the Kaliningrad Oblast is a Russian exclave between Lithuania and Poland.

- Ceded to Poland

- Everything east of the Oder-Neisse line plus Stettin. This amounted to most of Silesia, Eastern Pomerania, the Neumark region of Brandenburg, all of Posen-West Prussia, and the remainder of East Prussia not ceded to Russia.

- Placed under Soviet administration

- The following states, after merging with other German states, were formed after the war, then abolished in 1952 and finally recreated following the reunification of Germany in 1990:

- Brandenburg, from the remainder of the Province of Brandenburg.

- Saxony-Anhalt, from the bulk of the Province of Saxony. The remainder of the province became part of Thuringia.

- Mecklenburg-Vorpommern: the remainder of the Province of Pomerania (most of Western Pomerania) merged into Mecklenburg

- Saxony: the remainder of the Province of Silesia merged into Saxony.

- Placed under Allied administration

- The remainder of Prussia was merged with other German states to become the following states of West Germany:

- Schleswig-Holstein, from the province of Schleswig-Holstein (under British administration).

- Lower Saxony, from the province of Hanover (under British administration).

- North Rhine-Westphalia, from the province of Westphalia and the northern half of the Rhine Province (under British administration).

- Rhineland-Palatinate, from the southern remainder of the Rhine Province (under French administration).

- Hesse, from the province of Hesse-Nassau (under American administration).

- Württemberg-Hohenzollern, from the province of Hohenzollern (under French administration). The state was ultimately merged with Baden and Württemberg-Baden to form Baden-Württemberg.

- Berlin

- Divided into East Berlin under Soviet administration and West Berlin under Allied sectors of administration (British, French and American). West Berlin was surrounded by East Germany and ultimately was enclosed by the Berlin Wall. The two-halves were reunited after German reunification to form the modern German state of Berlin. A proposal to merge Berlin with the reformed state of Brandenburg was rejected by popular vote in 1996.

References

- Beckmanns Welt-Lexikon und Welt-Atlas. Leipzig / Vienna: Verlagsanstalt Otto Beckmann. 1931.

- "Council Control Law 46: Abolition of the State of Prussia". 25 February 1947.

- On 1 April 1881 Berlin was disentangled from the province of Brandenburg. Consisting of the mere one city of Berlin its lord mayor (German: Oberbürgermeister) fulfilled in personal union the task of the Landesdirektor and the city council the role of the provincial committee. While the role of the upper president was taken by the Prussian government-appointed chief of police (German: Polizeipräsident in Berlin). Cf. Meyers großes Konversations-Lexikon: 20 vols. – completely rev. and ext. ed., Leipzig and Vienna: Bibliographisches Institut, 1903–08, here vol. 2, article 'Berlin', p 700. No ISBN

- Weimar Commemorative 3 Mark Set 1929A WALDECK-PRUSSIA

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)