Christian Democratic Union of Germany

The Christian Democratic Union of Germany (German: Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands, CDU; German pronunciation: [ˈkʁɪstlɪç ˌdemoˈkʁaːtɪʃə ʔuˈni̯oːn ˈdɔʏtʃlants]) is a Christian-democratic[2][3] and liberal-conservative[4] political party in Germany. It is the major catch-all party of the centre-right[8][9][10] in German politics.[11][12]

Christian Democratic Union of Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | CDU |

| Chairperson | Armin Laschet |

| Vice Chairpersons | |

| Secretary General | Paul Ziemiak |

| Founded | 26 June 1945 |

| Headquarters | Klingelhöferstraße 8 10785 Berlin |

| Newspaper | Union |

| Youth wing | Young Union |

| Membership (November 2019) | |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Centre-right[6][7] |

| National affiliation | CDU/CSU |

| European affiliation | European People's Party |

| International affiliation | Centrist Democrat International International Democrat Union |

| European Parliament group | European People's Party |

| Colours | Orange (official) Black (customary) |

| Bundestag | 200 / 709 |

| Bundesrat | 22 / 69 |

| State Parliaments | 489 / 1,868 |

| European Parliament | 23 / 96 |

| Ministers-president of states | 6 / 16 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| www | |

Armin Laschet has been federal chairman of the CDU since January 2021. The CDU is the largest party in the Bundestag, the German federal legislature, 200 out of 709 seats, having won 26.8% of votes in the 2017 federal election. It forms the CDU/CSU Bundestag faction, also known as the Union, with its Bavarian counterpart the Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU). The group's parliamentary leader is Ralph Brinkhaus, a member of the CDU.

Founded in 1945 as an interdenominational Christian party, the CDU effectively succeeded the pre-war Catholic Centre Party, with many former members joining the party, including its first leader Konrad Adenauer. The party also included politicians of other backgrounds, including liberals and conservatives.[13] As a result, the party claims to represent "Christian-social, liberal and conservative" elements.[14] The CDU is generally pro-European in outlook.[15] Black is the party's customary colour. Other colours include red for the logo, orange for the flag, and black-red-gold for the corporate design.[16]

The CDU has headed the federal government since 2005 under Angela Merkel, who also served as the party's leader from 2000 until 2018. The CDU previously led the federal government from 1949 to 1969 and 1982 to 1998. Germany's three longest-serving post-war Chancellors have all come from the CDU; Helmut Kohl (1982–1998), Angela Merkel (2005–present), and Konrad Adenauer (1949–1963). The party also leads the governments of six of Germany's sixteen states.

The CDU is a member of the Centrist Democrat International, the International Democrat Union and the European People's Party (EPP). It is the largest party in the EPP with 23 MEPs. Ursula von der Leyen, the current President of the European Commission, is a member of the CDU.

History

Founding period

Immediately following the end of World War II and the foreign occupation of Germany simultaneous yet unrelated meetings began occurring throughout the country, each with the intention of planning a Christian-democratic party. The CDU was established in Berlin on 26 June 1945 and in Rheinland and Westfalen in September of the same year.

The founding members of the CDU consisted primarily of former members of the Centre Party, the German Democratic Party, the German National People's Party and the German People's Party. Many of these individuals, including CDU-Berlin founder Andreas Hermes, were imprisoned for the involvement in the German Resistance during the Nazi dictatorship. In the Cold War years after World War II up to the 1960s (see Vergangenheitsbewältigung), the CDU also attracted conservative, anti-communist former Nazis and Nazi collaborators into its higher ranks (like Hans Globke and Theodor Oberländer). A prominent anti-Nazi member was theologian Eugen Gerstenmaier, who became Acting Chairman of the Foreign Board (1949–1969).

One of the lessons learned from the failure of the Weimar Republic was that disunity among the democratic parties ultimately allowed for the rise of the Nazi Party. It was therefore crucial to create a unified party of Christian democrats – a Christian Democratic Union. The result of these meetings was the establishment of an inter-confessional (Catholic and Protestant alike) party influenced heavily by the political tradition of liberal conservatism. The CDU experienced considerable success gaining support from the time of its creation in Berlin on 26 June 1945 until its first convention on 21 October 1950, at which Chancellor Konrad Adenauer was named the first Chairman of the party.

Adenauer era (1949–1963)

In the beginning, it was not clear which party would be favored by the victors of World War II, but by the end of the 1940s the governments of the United States and of Britain began to lean toward the CDU and away from the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). The latter was more nationalist and sought German reunification even at the expense of concessions to the Soviet Union, depicting Adenauer as an instrument of both the Americans and the Vatican. The Western powers appreciated the CDU's moderation, its economic flexibility and its value as an oppositional force to the communists which appealed to European voters at the time. Adenauer was also trusted by the British.[17]

The party was split over issues of rearmament within the Western alliance and German unification as a neutral state. Adenauer staunchly defended his pro-Western position and outmanoeuvred some of his opponents. He also refused to consider the SPD as a party of the coalition until he felt sure that they shared his anti-communist position. The principled rejection of a reunification that would alienate Germany from the Western alliance made it harder to attract Protestant voters to the party as most refugees from the former German territories east of the Oder were of that faith as were the majority of the inhabitants of East Germany.[17]

The CDU was the dominant party for the first two decades following the establishment of West Germany in 1949. Adenauer remained the party's leader until 1963, at which point the former minister of economics Ludwig Erhard replaced him.[18] As the Free Democratic Party (FDP) withdrew from the governing coalition in 1966 due to disagreements over fiscal and economic policy, Erhard was forced to resign. Consequently, a grand coalition with the SPD took over government under CDU Chancellor Kurt Georg Kiesinger.

Opposition against social-liberal governments (1969–1982)

The SPD quickly gained popularity and succeeded in forming a social-liberal coalition with the FDP following the 1969 federal election, forcing the CDU out of power for the first time in its history. The CDU and CSU were highly critical of Chancellor Willy Brandt's "change through rapprochement" policy towards the Eastern bloc (Ostpolitik) and protested sharply against the 1970 treaties of Moscow and Warsaw that renounced claims to the former eastern territories of Germany and recognised the Oder–Neisse line as Germany's eastern border. The Union parties had close ties with the Heimatvertriebene associations (Germans who fled or were expelled from the eastern territories) who hoped for a return of these territories. Seven Bundestag members, including former vice chancellor Erich Mende, defected from the FDP and SPD to the CDU in protest against these treaties, depriving Brandt of his majority, and providing a thin majority for the CDU and CSU. In April 1972 the CDU saw its chance to return to power, calling a constructive vote of no confidence. CDU chairman Rainer Barzel was almost certain to become the new Chancellor. But not all parliamentarians voted as expected (it was later revealed that two CDU/CSU deputies had been bribed by the East German Stasi): Brandt won the vote and stayed in office. Thus, the CDU continued its role as opposition for a total of thirteen years. In 1982, the FDP withdrew from the coalition with the SPD and allowed the CDU to regain power.

Kohl era (1982–1998)

CDU Chairman Helmut Kohl became the new Chancellor of West Germany and his CDU/CSU–FDP coalition was confirmed in the 1983 federal election.

After the collapse of the East German government in 1989, Kohl—supported by the governments of the United States and reluctantly by those of France and the United Kingdom—called for German reunification. On 3 October 1990, the government of East Germany was abolished and its territory acceded to the scope of the Basic Law already in place in West Germany. The East German CDU merged with its West German counterpart and elections were held for the reunified country. Public support for the coalition's work in the process of German reunification was reiterated in the 1990 federal election in which the CDU–FDP governing coalition experienced a clear victory. Although Kohl was re-elected, the party began losing much of its popularity because of an economic recession in the former GDR and increased taxes in the west. The CDU was nonetheless able to win the 1994 federal election by a narrow margin due to an economic recovery.

Kohl served as chairman until the party's electoral defeat in 1998, when he was succeeded by Wolfgang Schäuble. Schäuble resigned in early 2000 as a result of a party financing scandal and was replaced by Angela Merkel, who remained the leader of the CDU until 2018. In the 1998 federal election the CDU polled 28.4% and the CSU 6.7% of the national vote, the lowest result for those parties since 1949; a red–green coalition under the leadership of Gerhard Schröder took power until 2005. In the 2002 federal election, the CDU and CSU polled slightly higher (29.5% and 9.0%, respectively), but still lacked the majority needed for a CDU–FDP coalition government.

Merkel era (2000–2018)

In 2005, early elections were called after the CDU dealt the governing SPD a major blow, winning more than ten state elections, most of which were landslide victories. The resulting grand coalition between the CDU/CSU and the SPD faced a serious challenge stemming from both parties' demand for the chancellorship. After three weeks of negotiations, the two parties reached a deal whereby CDU received the chancellorship while the SPD retained 8 of the 16 seats in the cabinet and a majority of the most prestigious cabinet posts.[19] The coalition deal was approved by both parties at party conferences on 14 November.[20] Merkel was confirmed as the first female Chancellor of Germany by the majority of delegates (397 to 217) in the newly assembled Bundestag on 22 November.[21] Since her first term in office, from 2005 to 2009, there have been discussions if the CDU was still "sufficiently conservative" or if it was "social-democratising".[22] In March 2009, Merkel answered with the statement "Sometimes I am liberal, sometimes I am conservative, sometimes I am Christian-social—and this is what defines the CDU."[23]

Although the CDU and CSU lost support in the 2009 federal elections, their "desired partner" the FDP experienced the best election cycle in its history, thereby enabling a CDU/CSU–FDP coalition. This marked the first change of coalition partner by a Chancellor in German history and the first centre-right coalition government since 1998. CDU candidate Christian Wulff won the 2010 presidential election in the third ballot, while opposition candidate Joachim Gauck (a Protestant pastor and former anti-communist activist in East Germany, who was favoured even by some CDU members) received a number of "faithless" votes from the government camp.

The decisions to suspend conscription (late 2010) and to phase out nuclear energy (shortly after the Fukushima disaster in 2011) broke with long-term principles of the CDU, moving the party into a more socially liberal direction and alienating some of its more conservative members and voters. At its November 2011 conference the party proposed a "wage floor", after having expressly rejected minimum wages during the previous years.[24] Psephologist and Merkel advisor Matthias Jung coined the term "asymmetric demobilisation" for the CDU's strategy (practised in the 2009, 2013 and 2017 campaigns)[25] of adopting issues and positions close to its rivals, e.g. regarding social justice (SPD) and ecology (Greens), thus avoiding conflicts that might mobilise their potential supporters. Some of the promises in the CDU's 2013 election platform were seen as "overtaking the SPD on the left".[26] While this strategy proved to be quite successful in elections, it also raised warnings that the CDU's profile would become "random", the party would lose its "essence"[24] and it might even be dangerous for democracy in general if parties became indistinguishable and voters demotivated.

President Wulff resigned in February 2012 due to allegations of corruption, triggering an early presidential election. This time the CDU supported, reluctantly, nonpartisan candidate Joachim Gauck. The CDU/CSU–FDP coalition lasted until the 2013 federal election, when the FDP lost all its seats in the Bundestag while the CDU and CSU won their best result since 1990, only a few seats short of an absolute majority. This was partly due to the CDU's expansion of voter base to all socio-structural groups (class, age or gender), partly due to the personal popularity of Chancellor Merkel.[27] After talks with the Greens had failed, the CDU/CSU formed a new grand coalition with the SPD.

Despite their long-cherished slogan of "There must be no democratically legitimised party to the right of CDU/CSU",[28] the Union has had a serious competitor to its right since 2013. The right-wing populist Alternative for Germany (AfD) was founded with the involvement of disgruntled CDU members. It drew on the discontent of some conservatives with the Merkel administration's handling of the European debt crisis (2009–14) and later the 2015 refugee crisis, lamenting a purported loss of sovereignty and control or even "state failure". Nearly 10 percent of early AfD members were defectors from the CDU.[29] In the 2017 election, the CDU and CSU lost a large portion of their voteshare: With 26.8 percent of party list votes, the CDU received its worst result since 1949, losing more than fifty seats in the Bundestag (despite an enlargement of the parliament). After failing to negotiate a coalition with the FDP and Greens, they continued their grand coalition with the SPD. In October 2018, Merkel announced that she would step down as leader of the CDU that December, but wanted to remain as Chancellor until 2021.[30]

Post-Merkel (2018–present)

On 7 December 2018, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer was elected as federal chairwoman of the CDU. Kramp-Karrenbauer was considered Merkel's ideological successor, though holding more socially conservative positions, such as opposition to same-sex marriage. Kramp-Karrenbauer's election saw a rise in support for the CDU in national polling, and her personal popularity was initially high.[31] However, she suffered a sharp decline in popularity in the lead-up to the 2019 European Parliament election, in which the CDU/CSU suffered its worst ever result in a national election with just 29%. Kramp-Karrenbauer thereafter remained one of the least popular politicians nationally.[32][33]

The CSU's Manfred Weber was the Spitzenkandidat for the European People's Party in the 2019 European Parliament election. However, the EPP group ultimately nominated the CDU's Ursula von der Leyen as their candidate for President of the European Commission; she was elected in July 2019, becoming the first woman to hold the office.[34]

Kramp-Karrenbauer resigned as party chair on 10 February 2020, in the midst of the 2020 Thuringian government crisis. The Thuringian CDU had been perceived as cooperating with the Alternative for Germany (AfD) to prevent the election of a left-wing government, breaching the long-standing taboo in Germany surrounding cooperation with the far-right. Kramp-Karrenbauer was perceived as unable to enforce discipline within the party during the crisis, which she claimed was complicated by unclear positions within the party regarding cooperation with the AfD and The Left, which party statute holds to be equally unacceptable. While the Thuringia crisis was the immediate trigger for Kramp-Karrenbauer's resignation, she stated the decision had "matured some time ago",[35] and media attributed it to the troubled development of her brief leadership.[36]

Kramp-Karrenbauer remained in office as Minister of Defence and interim party leader from February until the leadership election was held in January 2021.[37][38] Originally scheduled for April 2020, it was delayed multiple times due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and was ultimately held online. Minister-President of North Rhine-Westphalia Armin Laschet won the election with 52.8% of delegate votes. His main opponent was Friedrich Merz, who won 47.2% of vote; Merz had also run against Kramp-Karrenbauer in 2018 and been defeated. Laschet's election was seen as an affirmation of Merkel's leadership and the CDU's centrist orientation.[39]

Voter base

While Adenauer and Erhard co-operated with non-Nazi parties to their right, the CDU has later worked to marginalize its right-wing opposition. The loss of anti-communism as a political theme, secularization and the cultural revolutions in West Germany occurring since the 1960s have challenged the viability of the CDU.

In her 2005 campaign, Angela Merkel was unwilling to express explicitly Christian views while maintaining that her party had never lost its concept of values. Merkel and Bundestag President Norbert Lammert have been keen to clarify that CDU references to the "dominant culture" imply "tolerance and living together".[17] According to party analyst Stephan Eisel, her avoiding the values-issue may have had the opposite effect as she failed to mobilize the party's core constituency.[40]

The CDU applies the principles of Christian democracy and emphasizes the "Christian understanding of humans and their responsibility toward God". However, CDU membership consists of people adhering to a variety of religions as well as non-religious individuals. The CDU's policies derive from political Catholicism, Catholic social teaching and political Protestantism as well as economic liberalism and national conservatism. The party has adopted more liberal economic policies since Helmut Kohl's term in office as the Chancellor of Germany (1982–1998).

As a conservative party, the CDU supports stronger punishments of crimes and involvement on the part of the Bundeswehr in cases of domestic anti-terrorism offensives. In terms of immigrants, the CDU supports initiatives to integrate immigrants through language courses and aims to further control immigration. Dual citizenship should only be allowed in exceptional cases.

In terms of foreign policy, the CDU commits itself to European integration and a strong relation with the United States. In the European Union, the party opposes the entry of Turkey, preferring instead a privileged partnership. In addition to citing various human rights violations, the CDU also believes that Turkey's unwillingness to recognise Cyprus as an independent sovereign state contradicts the European Union policy that its members must recognise the existence of one another.

The CDU has governed in four federal-level and numerous state-level Grand Coalitions with the Social Democratic Party (SPD) as well as in state and local-level coalitions with the Alliance '90/The Greens. The CDU has an official party congress adjudication that prohibits coalitions and any sort of cooperation with either The Left or the Alternative for Germany.[41]

Internal structure

Party congress

The party congress is the highest organ of the CDU. It meets at least every two years, determines the basic lines of CDU policy, approves the party program and decides on the statutes of the CDU.

The CDU party congress consists of the delegates of the CDU regional associations, the foreign associations and the honorary chairmen. The state associations send exactly 1,000 delegates who have to be elected by the state or district conventions. The number of delegates that a regional association can send depends on the number of members of the association six months before the party congress and the result of the last federal election in the respective federal state. The foreign associations recognized by the federal executive committee each send a delegate to the party congress, regardless of their number of members.

Federal committee

The federal committee is the second highest body and deals with all political and organizational matters that are not expressly reserved for the federal party congress. For this reason it is often called a small party congress.

Federal executive board and presidium

The CDU federal executive heads the federal party. It implements the resolutions of the federal party congress and the federal committee and convenes the federal party congress. The CDU Presidium is responsible for executing the resolutions of the federal executive committee and handling current and urgent business. It consists of the leading members of the federal executive board and is not an organ of the CDU in Germany.

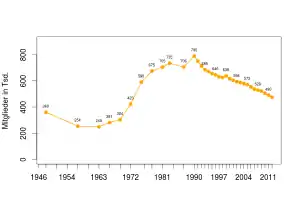

Members

Before 1966, membership totals in CDU organisation were only estimated. The numbers after 1966 are based on the total from 31 December of the previous year. In 2018, the CDU had 420,240 members.[42]

In 2012, the members' average age was 59 years. 6% of the Christian Democrats were under 30 years old.[43] A 2007 study by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation showed that 25.4% of members were female and 74.6% male. Female participation was higher in the former East German states with 29.2% compared to 24.8% in the former West German states.[44]

| State group | Chairman | Members | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDU Baden-Württemberg | Thomas Strobl | 74,669 | ||

| Berlin | Monika Grütters | 12,568 | ||

| Brandenburg | Ingo Senftleben | 6,797 | ||

| Bremen | Carsten Meyer-Heder | 3,246 | ||

| Hamburg | Roland Heintze | 9,697 | ||

| Hesse | Volker Bouffier | 47,789 | ||

| Mecklenburg-Vorpommern | Vincent Kokert | 6,038 | ||

| Lower Saxony | Bernd Althusmann | 72,813 | ||

| North Rhine-Westphalia | Armin Laschet | 165,273 | ||

| Rhineland-Palatinate | Julia Klöckner | 49,856 | ||

| Saarland | Tobias Hans | 20,651 | ||

| Saxony | Michael Kretschmer | 13,148 | ||

| Saxony-Anhalt | Holger Stahlknecht | 8,410 | ||

| Schleswig-Holstein | Daniel Günther | 26,674 | ||

| Thuringia | Mike Mohring | 12,035 | ||

Relationship to the CSU

Both the CDU and the Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU) originated after World War II, sharing a concern for the Christian worldview. In the Bundestag, the CDU is represented in a common faction with the CSU. This faction is called CDU/CSU, or informally the Union. Its basis is a binding agreement known as a Fraktionsvertrag between the two parties.

The CDU and CSU share a common youth organisation, the Junge Union, a common pupil organisation, the Schüler Union Deutschlands, a common student organisation, the Ring Christlich-Demokratischer Studenten and a common Mittelstand organisation, the Mittelstands- und Wirtschaftsvereinigung.

The CDU and CSU are legally and organisationally separate parties; their ideological differences are sometimes a source of conflict. The most notable and serious such incident was in 1976, when the CSU under Franz Josef Strauß ended the alliance with the CDU at a party conference in Wildbad Kreuth. This decision was reversed shortly thereafter when the CDU threatened to run candidates against the CSU in Bavaria.

The relationship of CDU to the CSU has historic parallels to previous Christian-democratic parties in Germany, with the Catholic Centre Party having served as a national Catholic party throughout the German Empire and the Weimar Republic while the Bavarian People's Party functioning as the Bavarian variant.

Since its formation, the CSU has been more conservative than the CDU. The CSU and the state of Bavaria decided not to sign the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany as they insisted on more autonomy for the individual states.[45] The CSU and the free state of Bavaria have a separate police and justice system (distinctive and non-federal) and have actively participated in all political affairs of the Bundestag, the German government, the Bundesrat, the parliamentary elections of the German President, the European Parliament and meetings with Mikhail Gorbachev in Russia.

Konrad Adenauer Foundation

The Konrad Adenauer Foundation is the think-tank of the CDU. It is named after the first Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany and first president of the CDU. The foundation offers political education, conducts scientific fact-finding research for political projects, grants scholarships to gifted individuals, researches the history of Christian democracy and supports and encourages European unification, international understanding and development-policy cooperation. Its annual budget amounts to around 120 million euro and is mostly funded by taxpayer money.[46]

Special organizations

Notable suborganisations of the CDU are the following:

- Junge Union (JU), the common youth organisation of the CDU and the CSU.

- Christian Democratic Employees' Association (CDA), a traditionally leftist association representing Christian-democratic wage earners.

- Evangelical Working Group of the CDU/CSU (EAK, together with the CSU), representing the Protestant minority in the party.

- Association of Christian Democratic Students (RCDS), the student organisation of the party.

- Lesbian and Gay Members of the Union (LSU), representing LGBT+ members of the CDU.

Chairperson of the CDU, 1950–present

| Chairperson | Period |

|---|---|

| Konrad Adenauer | 1950–1966 |

| Ludwig Erhard | 1966–1967 |

| Kurt Georg Kiesinger | 1967–1971 |

| Rainer Barzel | 1971–1973 |

| Helmut Kohl | 1973–1998 |

| Wolfgang Schäuble | 1998–2000 |

| Angela Merkel | 2000–2018 |

| Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer | 2018–2021 |

| Armin Laschet | 2021–present |

Parliamentary chairmen/chairwomen of the CDU/CSU group in the national parliament

| Chairperson of the CDU/CSU group | Period |

|---|---|

| Heinrich von Brentano di Tremezzo | 1949–1955 |

| Heinrich Krone | 1955–1961 |

| Heinrich von Brentano di Tremezzo | 1961–1964 |

| Rainer Barzel | 1964–1973 |

| Karl Carstens | 1973–1976 |

| Helmut Kohl | 1976–1982 |

| Alfred Dregger | 1982–1991 |

| Wolfgang Schäuble | 1991–2000 |

| Friedrich Merz | 2000–2002 |

| Angela Merkel | 2002–2005 |

| Volker Kauder | 2005–2018 |

| Ralph Brinkhaus | 2018–present |

German Chancellors from the CDU

| Chancellor of Germany | Time in office |

|---|---|

| Konrad Adenauer | 1949–1963 |

| Ludwig Erhard | 1963–1966 |

| Kurt Georg Kiesinger | 1966–1969 |

| Helmut Kohl | 1982–1998 |

| Angela Merkel | 2005–present |

Election results

Federal Parliament (Bundestag)

| Election year | Leader | No. of constituency votes | No. of party list votes | % of party list votes | No. of overall seats won | +/– | Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1949 | Konrad Adenauer | 5,978,636 | 25.2 | 115 / 402 |

CDU/CSU–FDP–DP | ||

| 1953 | 9,577,659 | 10,016,594 | 36.4 | 197 / 509 |

CDU/CSU–FDP–DP | ||

| 1957 | 11,975,400 | 11,875,339 | 39.7 | 222 / 519 |

CDU/CSU–DP | ||

| 1961 | 11,622,995 | 11,283,901 | 35.8 | 201 / 521 |

CDU/CSU–FDP | ||

| 1965 | 12,631,319 | 12,387,562 | 38.0 | 202 / 518 |

CDU/CSU–SPD | ||

| 1969 | Kurt Georg Kiesinger | 12,137,148 | 12,079,535 | 36.6 | 201 / 518 |

Opposition | |

| 1972 | Rainer Barzel | 13,304,813 | 13,190,837 | 35.2 | 186 / 518 |

Opposition | |

| 1976 | Helmut Kohl | 14,423,157 | 14,367,302 | 38.0 | 201 / 518 |

Opposition | |

| 1980 | 13,467,207 | 12,989,200 | 34.2 | 185 / 519 |

Opposition | ||

| 1983 | 15,943,460 | 14,857,680 | 38.1 | 202 / 520 |

CDU/CSU–FDP | ||

| 1987 | 14,168,527 | 13,045,745 | 34.4 | 185 / 519 |

CDU/CSU–FDP | ||

| 1990 | 17,707,574 | 17,055,116 | 36.7 | 268 / 662 |

CDU/CSU–FDP | ||

| 1994 | 17,473,325 | 16,089,960 | 34.2 | 244 / 672 |

CDU/CSU–FDP | ||

| 1998 | 15,854,215 | 14,004,908 | 28.4 | 198 / 669 |

Opposition | ||

| 2002 | Angela Merkel | 15,336,512 | 14,167,561 | 29.5 | 190 / 603 |

Opposition | |

| 2005 | 15,390,950 | 13,136,740 | 27.8 | 180 / 614 |

CDU/CSU–SPD | ||

| 2009 | 13,856,674 | 11,828,277 | 27.3 | 194 / 622 |

CDU/CSU–FDP | ||

| 2013 | 16,233,642 | 14,921,877 | 34.1 | 254 / 630 |

CDU/CSU–SPD | ||

| 2017 | 14,027,804 | 12,445,832 | 26.8 | 200 / 709 |

CDU/CSU–SPD |

European Parliament

| Election year | No. of overall votes | % of overall vote | No. of overall seats won | +/– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 10,883,085 | 39.0 (2nd) | 33 / 81 |

|

| 1984 | 9,308,411 | 37.5 (1st) | 32 / 81 |

|

| 1989 | 8,332,846 | 29.5 (2nd) | 24 / 81 |

|

| 1994 | 11,346,073 | 32.0 (2nd) | 39 / 99 |

|

| 1999 | 10,628,224 | 39.2 (1st) | 43 / 99 |

|

| 2004 | 9,412,009 | 36.5 (1st) | 40 / 99 |

|

| 2009 | 8,071,391 | 30.6 (1st) | 34 / 99 |

|

| 2014 | 8,807,500 | 30.0 (1st) | 29 / 96 |

|

| 2019 | 8,437,093 | 22.6 (1st) | 23 / 96 |

State Parliaments (Länder)

Note that the CDU does not contest elections in Bavaria due to the alliance with Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union in Bavaria.

| State Parliament | Election year | No. of overall votes | % of overall vote | Seats | Government | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | ± | Position | |||||

| Baden-Württemberg | 2016 | 1,447,249 | 27.0 (2nd) |

42 / 143 |

Greens–CDU | ||

| Berlin | 2016 | 288,002 | 17.6 (2nd) |

31 / 160 |

Opposition | ||

| Brandenburg | 2019 | 196,988 | 15.6 (3rd) |

15 / 88 |

SPD–CDU–Greens | ||

| Bremen | 2019 | 390,414 | 26.7 (1st) |

24 / 84 |

Opposition | ||

| Hamburg | 2020 | 445,631 | 11.2 (3rd) |

15 / 121 |

Opposition | ||

| Hesse | 2018 | 776,254 | 27.0 (1st) |

40 / 137 |

CDU–Greens | ||

| Lower Saxony | 2017 | 2,707,274 | 35.4 (2nd) |

50 / 137 |

SPD–CDU | ||

| Mecklenburg-Vorpommern | 2016 | 153,101 | 19.0 (3rd) |

16 / 71 |

SPD–CDU | ||

| North Rhine-Westphalia | 2017 | 2,796,683 | 33.0 (1st) |

72 / 199 |

CDU–FDP | ||

| Rhineland-Palatinate | 2016 | 677,507 | 31.8 (2nd) |

35 / 101 |

Opposition | ||

| Saarland | 2017 | 217,265 | 40.7 (1st) |

24 / 51 |

CDU–SPD | ||

| Saxony | 2019 | 695,560 | 32.1 (1st) |

45 / 119 |

CDU–SPD-Greens | ||

| Saxony-Anhalt | 2016 | 334,123 | 29.8 (1st) |

30 / 87 |

CDU–SPD–Greens | ||

| Schleswig-Holstein | 2017 | 470,312 | 32.0 (1st) |

25 / 73 |

CDU–Greens–FDP | ||

| Thuringia | 2019 | 241,103 | 21.8 (3rd) |

21 / 90 |

Opposition | ||

See also

- Archive for Christian Democratic Policy

- List of Christian democratic parties

- List of political parties in Germany

- Merkel-Raute, the signature gesture of Angela Merkel which is prominently featured in the CDU's campaign for the 2013 German federal election[47]

- Party finance in Germany

References

- "Parteien: CDU und SPD verlieren Mitglieder – Grüne legen deutlich zu". 16 January 2020 – via Die Zeit.

- Frank Bösch (2004). Steven Van Hecke; Emmanuel Gerard (eds.). Two Crises, Two Consolidations? Christian Democracy in Germany. Christian Democratic Parties in Europe Since the End of the Cold War. Leuven University Press. pp. 55–78.

- Ulrich Lappenküper (2004). Michael Gehler; Wolfram Kaiser (eds.). Between Concentration Movement and People's Party: The Christian Democratic Union in Germany. Christian Democracy in Europe Since 1945. 2. Routledge. pp. 21–32.

- Martin Steven (2018). Mark Garnett (ed.). Conservatism in Europe – the political thought of Christian Democracy. Conservative Moments: Reading Conservative Texts. Bloomsbury. p. 96.

- "Germany". Europe Elects. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- Conradt, David P. (2015), "Christian Democratic Union (CDU)", Encyclopædia Britannica Online, Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved 16 December 2015

- Miklin, Eric (November 2014). "From 'Sleeping Giant' to Left–Right Politicization? National Party Competition on the EU and the Euro Crisis". JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies. 52 (6): 1199–1206.

- Boswell, Christina; Dough, Dan (2009). Bale, Tim (ed.). Politicizing migration: opportunity or liability for the centre-right in Germany?. Immigration and Integration Policy in Europe: Why Politics – and the Centre-Right – Matter. Routledge. p. 21.

- Hornsteiner, Margret; Saalfeld, Thomas (2014). Parties and the Party System. Developments in German Politics 4. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 80.

- Detterbeck, Klaus (2014). Multi-Level Party Politics in Western Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 105.

- Mark Kesselman; Joel Krieger; Christopher S. Allen; Stephen Hellman (2008). European Politics in Transition. Cengage Learning. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-618-87078-3. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Sarah Elise Wiliarty (2010). The CDU and the Politics of Gender in Germany: Bringing Women to the Party. Cambridge University Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-521-76582-4. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Martin Seeleib-Kaiser; Silke Van Dyk; Martin Roggenkamp (2008). Party Politics and Social Welfare: Comparing Christian and Social Democracy in Austria, Germany and the Netherlands. Edward Elgar. p. 10.

- Sven-Uwe Schmitz (2009). Konservatismus. VS Verlag. p. 142.

- Janosch Delcker (28 August 2017). "Where German parties stand on Europe". Politico.

- "Das Corporate Design der CDU Deutschlands" (PDF). 17 October 2017.

- Paul Gottfried (fall 2007). "The Rise and Fall of Christian Democracy in Europe". Orbis.

- "Konrad Adenauer (1876–1967)". BBC News. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "Merkel named as German chancellor". BBC News. 10 October 2005. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- "German parties back new coalition". BBC News. 14 November 2005. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- "Merkel becomes German chancellor". BBC News. 22 November 2005. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- Melanie Haas (2009). Ralf Thomas Baus (ed.). Die CDU in der großen Koalition zwischen 2005 und 2007. Zur Zukunft der Volksparteien: Das Parteiensystem untr den Bedingungen zunehmender Fragmentierung. Konrad Adenauer Foundation. p. 20.

- "Mal bin ich liberal, mal bin ich konservativ, mal bin ich christlich-sozial – und das macht die CDU aus". Angela Merkel in the TV Show Anne Will, 22 March 2009. Cited in Andreas Wagner (2014). Wandel und Fortschritt in den Christdemokratien Europas: Christdemokratische Elegien angesichts fragiler volksparteilicher Symmetrien. Springer VS. p. 211.

- Udo Zolleis (2015). Reimut Zohlnhöfer; Thomas Saalfeld (eds.). Auf die Kanzlerin kommt es an: Die CDU unter Angela Merkel. Politik im Schatten der Krise: Eine Bilanz der Regierung Merkel 2009–2013. Springer VS. pp. 81–83.

- Christina Holtz-Bacha (2019). Bundestagswahl 2017: Flauer Wahlkampf? Spannende Wahl!. Die (Massen-)Medien im Wahlkampf. Springer VS. pp. 4–5.

- Manfred G. Schmidt (2015). Reimut Zohlnhöfer; Thomas Saalfeld (eds.). Die Sozialpolitik der CDU/CSU-FDP-Koalition von 2009 bis 2013. Politik im Schatten der Krise: Eine Bilanz der Regierung Merkel 2009–2013. Springer VS. pp. 413–414.

- Petra Hemmelmann (2017). Der Kompass der CDU: Analyse der Grundsatz- und Wahlprogramme von Adenauer bis Merkel. Springer VS. p. 162.

- Based on a quote by CSU leader and Bavarian minister-president Franz Josef Strauß, 9 August 1987. Quoted in SWR2 Archivradio, 15 October 2018.

- "Auch ein Landtagsabgeordneter wechselt AfD zählt 2800 Überläufer". N-tv. 5 May 2013.

- "Angela Merkel to step down in 2021". BBC News. 29 October 2018.

- "ARD-DeutschlandTREND Januar 2019" (PDF). tagesschau. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- "Kramp-Karrenbauer so unbeliebt wie nie". tagesschau. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- "Union verliert, Zugewinn für Linke". ZDF. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- "MEPs back von der Leyen as EU Commission head". BBC News. 16 July 2019.

- "Kramp-Karrenbauer: Entscheidung ist seit geraumer Zeit in mir gereift". handelsblatt.de. 10 February 2020. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- Almut Cieschinger (10 February 2020). "So rutschte die CDU in die Krise – eine Chronologie". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 11 February 2020.

- "Merkel heir Kramp-Karrenbauer to step down as CDU leader". POLITICO. 10 February 2020.

- "Germany: Angela Merkel's CDU to decide new leader on April 25 | DW | 24.02.2020". DW.COM.

- Lotus, Jean (16 January 2020). "Armin Laschet, Merkel ally, elected head of Germany's CDU party". United Press International.

- Stefan Eisel: Reale Regierungsopposition gegen gefühlte Oppositionsregierung Die Politische Meinung, Dezember 2005.

- "Präsidium und Bundesvorstand der CDU Deutschlands zum Tod von Walter Lübcke". Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands. 24 June 2019.

- Andrea Shalal (26 July 2018). "Senior German conservative chides party for bickering". Reuters. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "Ausnahme Piraten und Grüne: Parteien laufen Mitglieder weg" (in German). N-tv. 28 May 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "Die Mitglieder der CDU" (in German).

- Dieter Wunderlich (2006). "Gründung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland". Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- "2010 Annual Report" (in German). p. 93.

- "'Merkel diamond' takes centre stage in German election campaign". The Guardian. 3 September 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

Further reading

- Bösch, Frank (2004). Steven Van Hecke; Emmanuel Gerard (eds.). Two Crises, Two Consolidations? Christian Democracy in Germany. Christian Democratic Parties in Europe Since the End of the Cold War. Leuven University Press. pp. 55–78. ISBN 90-5867-377-4.

- Cary, Noel D. (1996). The Path to Christian Democracy: German Catholics and the Party System from Windthorst to Adenauer. Harvard University Press.

- Green, Simon; Turner, Ed, eds. (2015). Understanding the Transformation of Germany's CDU. Routledge.

- Kleinmann, Hans-Otto (1993). Geschichte der CDU: 1945–1982. Stuttgart. ISBN 3-421-06541-1.

- Lappenküper, Ulrich (2004). Michael Gehler; Wolfram Kaiser (eds.). Between Concentration Movement and People's Party: The Christian Democratic Union of Germany. Christian Democracy in Europe since 1945. Routledge. pp. 21–32. ISBN 0-7146-5662-3.

- Mitchell, Maria (2012). The Origins of Christian Democracy: Politics and Confession in Modern Germany. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11841-0.

- Wiliarty, Sarah Elise (2010). The CDU and the Politics of Gender in Germany: Bringing Women to the Party. Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Official website of the Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands

- Official website of the European People's Party

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_des_Landtags_von_Sachsen-Anhalt_IMG_6092_LR10_by_Stepro.jpg.webp)